Читать книгу The Mighty Orinoco - Jules Verne - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

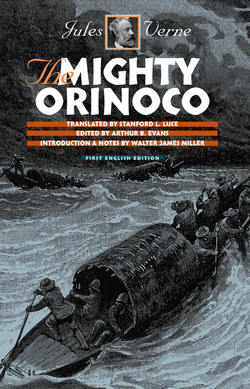

You hold in your hands a work that brings us closer to the climax of a decades-long effort to present the complete and the real Jules Verne to the English-speaking world. For this is the first time that his Le Superbe Orénoque, published in French in 1898, has appeared in English. And add this bonus, perhaps in partial recompense for Anglo-American publishers’ long neglect of the essential Verne: we English-speaking admirers can boast that we are the first—in his international audience—to honor him with such annotated critical editions.1

This Wesleyan University Press edition helps correct a long-standing censorship of the Great Romancer—for The Mighty Orinoco was the first of his works to be totally suppressed in English, largely for political reasons. The work you now contemplate also helps destroy two hoary myths about Verne: that he rarely wrote about women and love, and that he seldom attempted to portray the working class. Many such misunderstandings of Verne have been based on the persistent unavailability of several of his titles and on the gruesome fact that, with few exceptions, the “standard translations” of most other titles were greatly abridged—omitting from 20 to 40 percent of Verne’s originals.

The Mighty Orinoco also gives us one more sterling example of how Verne regarded science as inseparable from life. His reputation as a “futurist” is here reaffirmed as he involves his characters in a major nineteenth-century scientific question that would remain unsolved for fifty-seven years after he started to write this book—that is, until the middle of the twentieth century.

In Orinoco he further proves his enduring literary value by his masterful handling of a beautiful and ingenious plot and of such themes as the Quest for the Father and, more daunting, the basic androgyny of human personality. With deep intuition he recreates perfectly that nagging “anguish of modernity,” as Edmund J. Smyth so aptly terms it.2 This angst is produced, in part, by our conflicts over our self-righteous, self-serving “idea of progress” on the one hand and the human rights of those with alternative programs on the other.

Verne measures up to the challenge that these themes inevitably pose. He creates an array of unique characters who can successfully face such conflicts. These include a young French adventurer capable of rapid psychological growth, a builder of a utopia on the model set by Bishop Bartolomeo de las Casas, a charming Indian boy caught too early in one of life’s great crises, and several heroic, skillful boatmen.

This edition will also help us understand why Verne has been such a powerful influence on world literature in those countries where he could be read in his original French or in complete (e.g., Spanish, Russian, German) translations.

Some of the questions I’ve raised so far are best answered in detail later, in my notes; they cannot be developed here without destroying your enjoyment of Verne’s delicious suspense. But a few of these questions can and should be explored now because they will help us to keep Jules Verne’s novel and Stanford L. Luce’s translation in better perspective.

Most urgent perhaps is the question of “suppression,” for which leading scholars see a build-up of three cumulative causes. First, as Arthur B. Evans points out, “Verne was the victim of his own success.” By the end of the nineteenth century he had so popularized his new genre, the “scientific romance,” that a “veritable host of ‘Verne school’ writers”—mainly imitators—was now tapping his market. On that ground alone, English publishers grew wary about new translations. And, in those days, American publishers took their cues from the English.3

Second, translations of the earlier works—like From the Earth to the Moon (1865) and Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea (1870)—had been so shamelessly bungled and cut that Verne’s reputation in the English-speaking world had suffered almost irreparably. And so, of course, did sales. Just one example of his undeserved humiliation: in 1961, Galaxy magazine published an article on “The Watery Wonders of Captain Nemo,” in which Theodore L. Thomas discussed egregious “errors” in mathematics and science that he claimed he had found in Verne. As a result of such attacks, Verne was judged by critics and readers as unfit for even the juvenile market. This, mind you, about an author famous the world over for his ability to excite and satisfy readers from eight to eighty!

Shortly thereafter, I discovered how thoroughly Thomas had misrepresented Verne when Simon and Schuster asked me to prepare a new edition of the “standard translation” by the Reverend Lewis Page Mercier (who hid his sins behind a pen name: Mercier Lewis). Checking Lewis against the original French, I discovered that almost all the multitudinous errors the critics had attributed to Verne were actually the translator’s. Thomas and his editors, as well as many others in publishing, had simply failed to check whether the errors were actually in the original Verne. Lewis not only made childish mistakes in science and mathematics, he omitted 23 percent of Verne’s text. This omission, nearly a quarter of the novel, included most of the intellectual, theoretical, scientific, and—here’s the rub—political passages. Later, in doing an annotated translation of From the Earth to the Moon, I found that Lewis had gutted that work too for the English-speaking adult market.4

The third reason for suppressing Verne in English is best expressed by Brian Taves, senior author of The Jules Verne Encyclopedia. He flatly states that by 1898 political questions became the deciding factor in whether Verne books were translated into English. Heretofore censorship, alterations, and rewritings had sufficed to mute Verne’s politics, but now Verne books were “suppressed by simply not translating them” at all.5

What were these political questions that helped deprive English readers of the genuine Verne? Just as I had discovered in my annotated editions, Taves found that many other Verne works had been censored in whole or in part because they dealt with “questions of injustice and colonialism.”6 For example, take Verne’s recurrent discussion of England’s oppression of India. Lewis cut the indicting passage from Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea; W. H. G. Kingston rewrote such passages in The Mysterious Island; I. O. Evans simply omitted a whole chapter about English treatment of India from The Steam House.7

Verne’s oeuvre contains numerous attacks on imperialism. In From the Earth to the Moon, he satirizes American militarists who cannot keep their eyes off Mexico. In one of his short stories, an indigenous Peruvian dies heroically leading a rebellion against Spanish conquistadors (“Martin Paz,” 1875). In Purchase of the North Pole (1890), Verne challenges the very premise of colonial conquest. Mistress Branican (1891) contains the pronouncement that “annihilation of a race of human beings is the final word in colonial progress.”

Taves sees The Mighty Orinoco as portraying “colonial depredations within a tale of three … expeditions exploring the South American river.” In the opening chapter, Verne gives us his first hint that the white man’s standard description of the Indians is often false and tendentious. Note how slyly he uses the word “sometimes” in a sentence about “massacres and looting” (p. 13). Throughout the novel he portrays many nonwhites sympathetically, often warmly; the only genuine villain in Orinoco is a European. He accurately depicts a land dominated by a resented foreign race. Then he sums up these views by reminding readers that Jean Chaffanjon, France’s esteemed nineteenth-century explorer, had risked his life to prove that certain accusations, including the charges that the Guaharibos were dangerous and that Indians were all cannibals, were unjust. These were the accusations that had been used to justify the depredations the foreign rulers had visited on them.

The year Orinoco appeared in French, 1898, was the year procolonialist Anglo-American publishers decided to end their twenty-five-year tradition of promptly offering Verne’s latest work in English. The translation would have appeared between the time the United States took Cuba and Puerto Rico and the time Rudyard Kipling urged Americans to crush Filipino patriots as America’s part in taking up the “white man’s burden”—when an American general thought it would be necessary to kill half the Filipino rebels in order to “civilize” the other half. At the same time, the major powers were all rushing to plunder big chunks of Africa and Asia. Suppression of an anticolonialist writer was ideologically well timed.

Yet when you go from this introduction to the text of Orinoco itself, you will be properly perplexed. In the very opening chapter, Verne drops an unpleasant remark about “Negro blood.” Throughout, he disparages many Indians and “half-breeds,” using the word “savages” all too recklessly. He fails now and then to think of the Indians’ side of the story: they cannot forget that for centuries they have been invaded and enslaved by the white man.

But there are background circumstances that become relevant here. All his life Verne waxed hot and cold about the idea of progress. Scholars used to think that he was optimistic on that subject mainly at the beginning of his career and grew more pessimistic as his life wore on. But the recent discovery of the manuscript of Paris in the XXth Century (written in 1863 but not published until 1994) makes it clear that Verne had been deeply ambivalent about “progress” from the very start. The pessimism of Paris caused his publisher to reject it; not until Verne was famous could he once again reveal that side of himself.

“Progress,” colonialism, and “race” stand in a reliable relationship to each other in Verne’s moods. When he felt confident about “progress,” he saw it as the work of civilization, which in his day meant the advances of the white race. Any race opposing the spread of civilization (like the Sioux in Around the World in Eighty Days) was unfortunately standing in the way of the white race’s “manifest destiny.” But whenever Verne doubted “progress,” his tolerance of so-called anti-progress forces flourished. Verne himself usually opposes “colonialism,” which is what “spreading civilization” tends to be all about. And whenever he examines a nonwhite close up—as when he portrays Gomo in Orinoco—his basic human sympathy dominates all other considerations. Gomo is not nonwhite—he is a fellow person, an equal.

We must consider too the climate created by Darwin. Although Verne was not an out-and-out Darwinist, he, like most nineteenth-century intellectuals, was aware that history involves evolution. The prevailing idea—even among many social scientists—was that the white race was the first to reach the top rung on the evolutionary ladder. Other races were still evolving, presumably up the same ladder. Well into the twentieth century it was customary for prominent international leaders such as Herbert Hoover to speak of “the lower races.” Missionaries—of whom we meet a few in Orinoco—saw it as their duty to help these people hasten their climb up the ladder. But the imperialists’ purpose often overrode the clergy’s.

One other important idea: Verne seemed compelled to give voice—in his more than sixty books—to virtually every point of view, from anarchism and anti-Semitism to fascism and socialism. And here it’s urgent to take an honest look at literary history. We simply must admit that, from Chaucer to Shakespeare to Dickens, our greatest writers imbibed such biases as anti-Semitism and male supremacy as part of their normal religious upbringing, their everyday hearsay. As late as 1940, one of our leading poets, W. H. Auden, an Oxford graduate, told me that it was impossible to escape such taint even in the great British universities. (Admirers of the 1981 film Chariots of Fire will understand the subtleties in what Auden meant.) It’s a sobering realization that Jules Verne (1828–1905) and Charles Dickens (1812–1870), when compared to most of their contemporaries, prove to be quite broadminded.

So which of Verne’s conflicting attitudes toward colonialism represents his own deepest feelings? For Jean Chesneaux, author of the authoritative work on the subject,8 for Taves, and for me, Verne’s dominant tone, the stronger underlying emotion, the full power of Verne’s Id, connote anti-imperialism.

From the viewpoint of his publishers in English-speaking lands, Verne’s lapses into colonialist and racist attitudes did not outweigh his frequent condemnations of imperialism. So they first bowdlerized Verne’s books and then discontinued them. After all, there were hordes of writers taking a 100 percent procolonialist stance, glorifying the major powers for taking up “the … burden.” There was no need to continue publishing a writer who had mixed feelings about progress, civilization, and imperialism. And, at the risk of committing “presentism,” we will examine the ramifications of Verne’s conflict more thoroughly in the notes.

Verne usually juxtaposes Romanticist imagination against Positivist logic. As Evans has demonstrated in his Jules Verne Rediscovered (1988), this proves to be one of Verne’s best ways of achieving narrative tension.9 In The Mighty Orinoco he also uses an additional version of this approach: he juxtaposes the Quest for the Father against the experience of androgyny. The first is patriarchal in nature, the second egalitarian. Both are archetypal in their appeal. Verne launches the Father Quest early in his story and unveils the androgyny question midway through. Both themes involve the use of disguise; add surprises about the real identity of a character or two, and we have an example of perfect plotting.

In the Quest for the Father, Verne immerses us in a mainstream theme in Western literature at least as old as Homer (eighth century B.C.E.?). Ever since Telemachus set out to find his king-father Odysseus in The Odyssey, writers frequently remind us that in patriarchal society the male parent symbolizes the center of organization and authority, a source of meaning, purpose, and identity, a landmark of continuity. As the Freudians see it, one cannot achieve one’s own full development until one comes to terms with one’s father. As Jung expands the concept, that means exploring one’s legacy from both the male and female sides (a point that also becomes pertinent in our story).

The Vernian Quest, though, need not be for one’s biological father, as it is in Orinoco and in The Children of Captain Grant (1868). It can be an unconscious search for a “perfect father,” a father figure stronger or more influential than the biological father. In Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, Professor Aronnax’s irrational attraction to Captain Nemo has been seen as fulfilling such a deep psychological need. And Conseil’s blind dependence on the professor is an extreme example. (It illustrates, too, Verne’s use of counterpoint, a technique prominent also in Orinoco.) French psychoanalytic critics have viewed Verne’s portrayals of father-seeking characters, as in Orinoco, as reflecting his own search for and reliance on his own “perfect father,” his publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel. And indeed, Verne paints the father found in Orinoco as a perfectly idealized patriarch.

It’s possible that Verne chose the problem of the Father Quest because it provides a beautiful parallel to his main scientific theme: the hunt for the source of the mighty Orinoco. This scientific search gives Verne his chance to introduce this work with a comic scene, with slapstick characters; comedy is often his way of educating his reader painlessly about a question in science. But this theme, too, has its serious psychological aspects. Going upstream is a symbolic way of going back in one’s own life, learning about its many tributaries, its continuous variations within one central, domineering, inexorable flow. In this larger sense, several of the characters are heading toward the discovery of their own nature. And readers are unconsciously but gratefully associating to their own sources and flow.

Symbolic too is the fact that the upstream struggle leads us to a utopia that not only, as suggested earlier, seems based on the de las Casas approach, but also matches other classic utopian efforts. The Orinoco utopia, like Plato’s, thrives under a philosopher-king and, like Sir Thomas More’s, is created by an outsider. One might not want to live in this particular utopia, but it serves the usual function of such fictional “good places/no places”: it prompts us to dream up our own solution.10

As his narrative representative of the Positivist approach, Verne creates Jacques Helloch, a young scientist on an official mission for the French government. His is a supreme mind that can expand beyond his geographical sciences to solve psychological and paramilitary problems that complicate his professional and personal quests. Not the least of these is a major Romanticist situation that proves to be larger than love of Nature. Verne gives Helloch an associate, Germain Paterne, whose very name (“cousinly and kind”) aptly describes the manly bond between them and provides a bit of irony, for Germain is far from paternal in action, but much so in understanding.

In creating Sergeant Martial, Verne pulls off an unexpected tour de force in characterization. At the beginning, Verne tricks us into seeing the retired noncom simply as a stereotype of the crusty old soldier. We only gradually realize that Martial is a man with volcanic internal problems that cause his brusqueness and lapses in politeness and clear thinking. A tiny example: He has reluctantly gone on a serious mission that requires him to violate a direct order from his beloved colonel. This creates an understandable internal conflict for Martial, yet near the end of the story he resolves some serious questions with just a few quick words, and is allowed at last to function like a decisive military mind.

These promises about the joys of Verne’s characterizations must stop here in order to preserve your right to savor suspense. Discussion of other characters and the androgyny theme must wait for the notes. You might appreciate, however, a few reminders about the political situation in South America at the time of Verne’s story—the kinds of things Verne’s original audience knew and that he would spell out if he were writing for us today.

For centuries, Spain had controlled her American colonies with a firm racist policy. Only men born in Spain itself (peninsulares) could serve in colonial governments; even whites born in the Americas (Creoles, criollos) were given little chance to gain any administrative experience. Of course, persons of mixed white and Indian blood (mestizos), of mixed white and African blood (mulattoes), and of mixed Indian and black heritage (zambos), as well as full-blooded Indians and Africans all had less and less chance, in that descending order.

Simón Bolívar (1783–1830), “The Liberator,” solved some of these problems but created many new ones. He headed the political faction that wanted to transfer political power in Venezuela from the peninsulares to the Creole aristocrats, continuing to exclude the mixed masses from government. When the Spaniards were finally thrown out in the 1820s, the civilians remaining—even the Creoles—had insufficient know-how to take over the reins of administration. In the ensuing chaos (essentially a complex class and race struggle), only the caudillos, the military leaders, had the resources and experience to govern—and they did so in their own way.11

As our story opens, in 1893, the first three Venezuelans we meet—and many thereafter—are of European descent. With his Positivist mind-set, Verne carefully identifies most of the succeeding characters according to their places in the scheme we’ve outlined here. The first high government official we meet is a military governor. The president is a general. We shall monitor the details as they demand notes.

As you head upstream with Verne, you’ll make discoveries gustatory as well as geographic, social, and psychological. According to his grandson, Jean Jules-Verne, the author was no gourmet. He sat in a low chair at table to be nearer his plate, able to shovel his food down more easily. But in his imagination, at least, he actually savored and judged the whole world’s menus. In Verne’s Extraordinary Voyages, Andrew Martin points out, “diet, no less than travel (the two are effectively inseparable), furnishes an organizing metaphor … to the accumulation of knowledge. Nutrition and cognition … are serviced by an identical vocabulary and coupled by a unitary philosophy.”12

So prepare now for the oily toughness of possum, the surprise of stewed earthworm, cooked lice, and termites, but also for fragrant ducks “better than any European variety” and “monkey roasted until a golden brown, truly a succulent meal.”

And let the Quest—for father, fulfillment, and food—begin.

WALTER JAMES MILLER

Professor of English

School of Continuing and Professional Studies

New York University