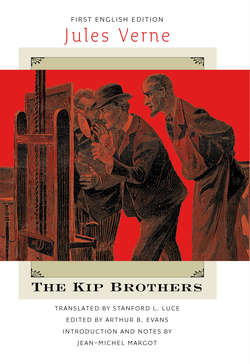

Читать книгу The Kip Brothers - Jules Verne - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

Vin Mod at Work

The distance between Dunedin and Wellington, through the strait that separates the two large islands, is less than four hundred miles.1 If the northwest breeze held steady and the sea remained calm along the coast, at the rate of ten miles an hour, the James Cook would arrive the next day in Wellington.

During this short crossing, would Flig Balt be able to execute his plan, taking over the brig after getting rid of the captain and his allies and sailing it toward the distant Pacific isles where he would find safety and act with total impunity?

We know how Vin Mod intended to proceed: Mr. Gibson and the men who were faithful to him would be surprised and thrown overboard before being able to defend themselves. But as of today, it was necessary to bring Len Cannon and his comrades into the plot—which would not be very difficult—in order to feel them out beforehand on this subject and be assured of their cooperation. That’s what Vin Mod planned to do during the first day of navigation, and then take action that very night. No time to lose. In twenty-four hours, the brig, reaching Wellington, would take on Mr. Hawkins and Nat Gibson as passengers. So, that night, it was important that the James Cook be taken over by Flig Balt and his accomplices. If not, the chances of success would be substantially diminished, and a second opportunity might perhaps not be found.

As for the question of whether or not Len Cannon, Sexton, Kyle, and Bryce would consent to join them, Vin Mod did not worry much about it. He knew that such faithless and lawless individuals, who have neither conscience nor scruples, are always attracted by the prospect of profitable deals in these regions of the Pacific, where justice cannot easily reach them.

The southern island of New Zealand,2 Tawaï-Pounamou, is said to resemble the form of a long rectangle, swollen in its lower part and somewhat obliquely laid out from southwest to southeast. On the contrary, the northern island, Ikana-Maoui, appears as an irregular triangle, its southernmost tip ending in a narrow tongue of land projecting out to the point of North Cape.

The coast that the brig followed is very jagged, banked with enormous rocks with bizarre shapes, which at a distance resemble gigantic mastodons fallen upon the shores. Here and there a succession of archways represents the periphery of a monastery, against which the waves, even in fine weather, hurl themselves furiously with a formidable roar. Any ship that was to find itself on the shore at high tide would be irredeemably lost; three or four rolls of the sea would demolish it. Fortunately, if it were seized by the tempest from the east or from the west, there would be a chance it might slip between the furthermost promontories of New Zealand. Moreover, there are two straits where it is possible to find shelter if you miss your entry into the ports: Cook’s, which separates the two islands, and Foveaux’s,3 open between Tawaï-Pounamou and Stewart4 Island, at its southern end. But one must beware of the dreadful reefs of the Snares,5 where the waves of the Indian Ocean and those of the Pacific collide, an area that is abundant in maritime disasters.

Inland from the coast extends a powerful mountain chain hollowed out by craters and furrowed by waterfalls, which feed rivers that are sizable despite their limited range. On the mountain slopes rise tiers of forests whose trees are huge beyond measure, pines a hundred feet tall and some twenty feet in diameter, cedars with olive-tree leaves, the resinous “koudy,” the “kaïkatea” with resistant leaves and red berries whose trunks are bare of branches except at the top.

Len Cannon and Bryce

If Ikana-Maoui can be proud of the richness of its soil, the vigor of its fertility, and that vegetation which rivals in certain areas the most brilliant productions of tropical flora, Tawaï-Pounamou has less to be grateful for. At the most a tenth of the territory can be cultivated. But in some special areas, the natives can still harvest a bit of Indian corn, various herbaceous plants, potatoes in abundance, and a profusion of ferns, the “pteris esculenta,” from which they make their principal food.

The James Cook at times approached so close to the shore, which Harry Gibson knew very well, that birdsong could be clearly heard on board ship, among others that of the “pou,” the most melodious. There was also the guttural cry of various parrots, ducks with yellow beaks and feet of scarlet red, without mentioning numerous other aquatic species, whose most hardy representatives flew among the rigging of the ship. And also, when the ship’s hull troubled their frolicking, with what rapidity fled those cetaceans, sea elephants, sea lions, and those multitudes of seals sought for their oily fat and their thick fur, two hundred of them producing nearly a hundred barrels of oil!

The weather held steady. If the breeze fell, it would not be before evening, since it came from land and, falling, would be blocked by the mountain chain.

Under a beautiful sun, the breeze blew through the higher zones and rapidly pushed the brig, which carried its staysail and its starboard studding sail. There was scarcely time to slacken the sails, to alter their course. So the new crewmembers could appreciate the sea-going qualities of the James Cook.

Around eleven o’clock, Mount Herbert, a bit before the port of Omaru,6 showed its swollen peaks rising to five thousand feet above sea level.

During the morning, Vin Mod sought in vain to talk with Len Cannon, whom he considered, and fairly, as the most intelligent and influential of the four recruits from Dunedin. Mr. Gibson, as we know, had ordered his sailors not to stay together on the same watch, and it was better, indeed, that they be kept separated from each other. But, not having to maneuver, the captain now left to the bosun the surveillance of the ship and he was busy in his cabin, updating the ship’s log.

At that moment Hobbes was at the helm. Flig Balt was strolling from the mainmast to the stern, on either side of the crew quarters. Two other sailors, Burnes and Bryce, were going back and forth along the rail without exchanging a word. Vin Mod and Len Cannon happened to be together downwind, and their conversation could not be heard by anyone.

When Jim, the cabin boy, approached them, they dismissed him rather curtly, and even, just to be safe, Bosun Balt sent him off to polish some of the copper instruments on the bridge.

As for the two other comrades of Len Cannon, Sexton and Kyle, they were not on duty and preferred fresh air to the stuffy atmosphere of their quarters. Koa, the cook, on the foredeck, amused them with his crude remarks and his abominable grimaces. This native was very proud of the tattoos on his face, torso, and limbs, this “moko”7 from New Zealand where the skin is deeply furrowed instead of scratched, as is done by other people of the Pacific. This operation of “moko” is not practiced on all the natives. The “koukis” or slaves are not worthy of it, nor are people of the lower class, unless they have distinguished themselves at war by some feat of arms.

So Koa took extraordinary pride in them.

And—which seemed to greatly interest Sexton and Kyle—he was pleased to give them a detailed explanation about each of his tattoos; he told of what circumstances his chest had been decorated with this or that design; he pointed at his forehead, which bore his name engraved permanently, and which for nothing in the world would he erase.

Moreover, among such natives, their cutaneous system, thanks to these operations that extend over the whole surface of the body, gains a great deal in thickness and solidity. Hence their resistance to cold during the winter and to mosquito bites. How many Europeans, at this expense, would thank themselves for being able to brave the attack of those accursed insects!

A tattooed New Zealand native*

While Koa, feeling himself instinctively attracted by a quite natural sympathy toward Sexton and his comrade, was setting up the basis of a strong friendship, Vin Mod was working on Len Cannon who, for his part, was most happy to see him approach:

“Eh, Cannon, my friend,” said Vin Mod, “so here you are aboard the James Cook. A pretty fair ship, isn’t she? And she’ll spin off eleven knots without your having to hold her hand.”

“So you say, Mod.”

“And with a fine cargo in her belly. Worth a lot …”

“So much the better for her owner.”

“Owner, sure … or anybody else … In the meantime, all we have to do is cross our arms while she’s running good.”

“Today it’s fine,” replied Cannon. “But tomorrow … who knows?”

“Tomorrow … next day … on and on!” exclaimed Vin Mod, patting Len Cannon’s shoulder. “But it’s better than just staying on land, right? Where would you be, your friends and you, right now if you weren’t here?”

“At the Three Magpies, Mod.”

“No, Adam Fry would’ve thrown you out, after the way you treated him. Then the police would’ve taken you in, all four of you. And I suppose, since this wouldn’t be your first appearance in court, they’d have favored you with one or two good months of rest in the Dunedin prison.”

“Prison on land or brig at sea, all the same thing,” answered Len Cannon, who didn’t sound too resigned to his fate.

“Oh, come now!” exclaimed Vin Mod, “sailors talking like that! …”

“It wasn’t our idea to sail away,” declared Len Cannon. “If it wasn’t for that miserable brawl yesterday, we’d already be off to Otago.”

“To work, to slave, to die of hunger and thirst, of course, but what for?”

“To make a fortune …,” Len Cannon replied.

“Make a fortune! … by placer mining?” answered Vin Mod. “Why there’s nothing left to extract from there. Haven’t you seen what they look like? The ones they’ve brought back? Just stones! All you want! And you can load yourself up with them, just so you won’t come back with empty pockets! As for the nuggets, the harvest is over, and they don’t grow back again from one day to the next nor even from one year to the next!”8

“I know men who don’t mind leaving their ship for the deposits in Clutha …”

“Me … I know four who won’t regret having embarked on the James Cook instead of taking off for the interior!”

“You saying that for us?”

“For you and two or three other gaffers like you!”

“And you’re trying to make me believe a sailor earns enough for a good life, eating and drinking the rest of his days for taking care of a captain and an owner?”

“Of course not,” replied Vin Mod, “unless he does it for his own account!”

“And how does that work? When we don’t own the ship?”

“Someday you’ll get to be an owner …”

“And you think that me and my friends have enough money in a Dunedin bank to buy a ship?”

“No, my friend. If you ever had savings, they passed right through the hands of Adam Frye and other bankers of that sort!”

“Well, Mod, no money, no ship. And I don’t think that Mr. Gibson is of a mood to make us a gift of his own.”

“No … but you know, misfortunes do happen! If Mister Gibson were to disappear … An accident, falling into the sea … that happens to the best of captains. One good wave, doesn’t take more to do you in, and at night … without anyone noticing … and in the morning nobody’s there …”

Len Cannon looked at Vin Mod, eye to eye, wondering if he understood.

The other continued:

“And then what happens? The captain’s replaced, and in this case it’s the second in command who takes over the ship, or if there’s no second in command, it’s the lieutenant.”

“And if there isn’t any lieutenant …,” added Len Cannon, lowering his voice and giving his interlocutor a nudge with his elbow, “if there’s no lieutenant, it’s the bosun …”

“As you say, my friend, and with a bosun like Flig Balt you could go a long way …”

“Not where you should go?” insinuated Len Cannon, tossing him a sideways glance.

“No … But it’s where you want to go …” said Vin Mod. “Where real money can be made. Good cargoes … Mother of pearl, copra, spices … all of it in the hold of the Little Girl.”9

“What do you mean … Little Girl?”

“That would be the new name of the James Cook … A pretty name, isn’t it? It should bring us luck!”

In any event, whether it carried this name or some other—although Vin Mod seemed especially fond of the new one—there were definite possibilities here. Len Cannon was intelligent enough to pick up on the fact that this proposal was being addressed to his comrades of the Three Magpies and to himself. Scruples would certainly not hold them back. But, before getting involved, he needed to understand things thoroughly, and on what side his best interests would lie. So after several moments of reflection, Len Cannon, who cast his eyes about to be sure no one could hear him, said to Vin Mod:

“Let’s hear it.”

Vin Mod then informed Len Cannon of the entire scheme as Flig Balt had planned it. Len Cannon, quite ready to take on such a proposition, showed neither surprise on hearing the details, nor repugnance in discussing them, nor hesitation in accepting them. Getting rid of Captain Gibson and some sailors who would have refused to enter into rebellion against him, take over the brig, change its name and, if necessary, its nationality, traffic across the Pacific, equal shares with the profits, all that was sufficiently appealing to the rogue. Nevertheless, he wanted some guarantees, and he wanted to be assured that the bosun was in on this with Vin Mod.

“This evening at a quarter to eight, while you’re at the helm, Flig Balt will talk to you, Len. Keep your ears open.”

“And he’s the one who’ll take command of the James Cook?” asked Len Cannon, who would have preferred not being under anyone’s orders.

“Ah, of course … devil take us! …,” replied Vin Mod. “You’ve got to have a captain, for sure. Only, it’s you, Len, your friends and us who will be the owners!”

“It’s a deal, Mod. Soon as I get a chance to talk to Sexton, Bryce, and Kyle, I’ll tip them off to this affair.”

“It’s just that it’s real urgent.”

“As much as that?”

“Yes … tonight, and, once the new masters are in charge, we’ll head out!”

So Vin Mod explained why the job had to be done before their arrival in Wellington, where Mr. Hawkins and the Gibson son would come aboard.

With two more men, the outcome would be less sure. In any case, if it weren’t for the coming night, it would have to be for the next, no later … or there would be less chance of success.

Len Cannon understood those reasons. When evening came, he would tell his friends, in whom he had as much confidence as in himself. From the moment the bosun put out the command, they would obey him. But first, Flig Balt had to confirm everything that Vin Mod had said. Two words would be enough, and a handshake to seal the pact. And by St. Patrick! Len Cannon would not demand a signature. What was promised would be kept.

In short, just as Vin Mod had indicated, toward eight o’clock, when Len Cannon was at the helm, Flig Balt left the crew’s quarters and headed aft. The captain was there at that time, and he had to wait for him to return to his cabin after having given out the orders for the night.

The northwest breeze held steady, although it had dropped a bit at sunset and it would not be necessary to change sails; perhaps they should only bring along the big topgallant and the little one. The brig would stay under its topsails, its low sails, and its jibs. Besides, it was less close to the wind, waiting to head toward the northeast. The sea promised to be calm until morning.

The James Cook, outside the port of Timaru,10 was about to cross the vast bay that indents the coastline, known by the name of Canterbury Bight. In order to cut around the Banks peninsula that encloses it, the ship would have to alter the course by two points to the east and navigate close-hauled to the wind.

Mr. Gibson braced the yards and hauled in the sheets in order to follow that direction. When day came, provided that the breeze did not utterly fall, he counted on having left behind Pompey’s Pillars to find himself abeam of Christchurch.11

After his orders were carried out, Harry Gibson, to the great frustration of Flig Balt, remained on the bridge until ten o’clock, sometimes exchanging some words with him, sometimes seated on the coping. The bosun, forewarned by Vin Mod, found himself unable to talk with Len Cannon.

Finally, everything settled down on board. The brig would not have to alter its route until three or four o’clock in the morning, when they would be in view of the port of Akaroa.12 So Mr. Gibson, after one last look at the horizon and the sail spread, returned to his cabin, which let in daylight on the forward side.

The discussion between Flig Balt and Len Cannon did not take long. The bosun confirmed the proposals of Vin Mod. No halfway measures: they’d throw the captain overboard after surprising him in his room, and since they could not count on Hobbes, Wickley, and Burnes, they’d throw them overboard as well. Len Cannon had only to reassure himself on the cooperation of his three comrades.

“But when?” asked Len Cannon.

“Tonight,” replied Vin Mod.

“What time?”

“Between eleven and midnight,” replied Flig Balt. “At that moment, Hobbes will be on duty with Sexton; Wickley will be at the helm. Won’t have to pull them from their post … And after we’ve gotten rid of those honest seamen …”

“Understood,” replied Len Cannon, feeling neither hesitation nor a twinge of conscience.

Then giving up the helm to Vin Mod, he headed for the bow in order to let Sexton, Bryce, and Kyle know what was going on.

Arriving at the mizzenmast, he looked for Sexton and Bryce in vain; they were supposed to be on duty but neither was there.

Wickley, whom he asked, just shrugged his shoulders.

“Where are they?” Len Cannon asked.

“In their quarters … dead drunk … both of them!”

“Ah, those louts,” murmured Len Cannon. “They’ll be out of it all night long. Nothing to be done about that!”

Back at their quarters, he found his comrades sprawled out on their cots. He shook them … Real louts, for sure! … They had stolen a bottle of gin from the storeroom. They drained it, to the last drop. Impossible to drag them out of their stupor, they wouldn’t revive until morning. Impossible to tell them about Vin Mod’s plans! Certainly couldn’t count on them to execute his plans before sunrise, and without them, the sides were too unequal!

When Flig Balt was informed, one can well imagine his rage. Vin Mod could not calm him down without great effort. He too would have sent both of them to the gallows, those wretched drunks! But anyway, nothing was permanently lost. What couldn’t be done that night would simply be done the next. They’d keep an eye on Bryce and Sexton and stop them from drinking. In any case Flig Balt would be careful not to denounce them to the captain, neither for drunkenness, nor for stealing the bottle. Mr. Gibson would send them to the bottom of the hold until the brig reached Wellington, then turn them over to the maritime authorities, and disembark perhaps Len Cannon and Kyle as well, as Vin Mod saw it. It would be wise not to say a word. Moreover, sailors do not denounce each other. Neither Hobbes, nor Wickley, nor Burnes, nor even the ship’s boy would talk, and the captain would have no cause to intervene.

The night went by, and nothing disturbed the calm aboard the James Cook.

When Harry Gibson went up to the bridge early the next morning, he noted that the men on duty were at their post, and the brig on a proper course at right angles to Christchurch after having passed the Banks Peninsula.

The day of the 27th was off to a good start. The sun broke above the horizon and promptly dissipated the haze. One could believe that the sea breeze would soon engulf the bay, but beginning at seven o’clock it came from the land and, no doubt, would keep to the northwest as the day before. By hugging the wind, the James Cook would reach the port of Wellington without changing its tack.

“Nothing new?” asked Mr. Gibson of Flig Balt when the bosun came out of his cabin, where had spent the last hours of the night.

“Nothing new, Mr. Gibson,” he replied.

“Who’s at the helm?”

“The sailor Cannon.”

“You haven’t had to admonish the new recruits while on duty?”

“Not at all, and I think those men are better than they seem.”

“So much the better, Balt, for I believe that in Wellington as in Dunedin they must be short of crews.”

“That’s probable, Mr. Gibson.”

“And, all in all, if I could work it out with these fellows …”

“It would be for the best,” answered Flig Balt.

The James Cook, continuing north, went along the coast at just three or four miles an hour. The details came into view more clearly under the heat of the sun’s rays. The high mountains of the Kaikoura,13 which cross the province of Marlborough,14 raised their capricious ridges to a height of ten thousand feet. On their flanks spread thick forests, gilded with sunlight, as streams of water flowed down toward the coastline.

Yet the breeze seemed to be calming, and the brig that day would make fewer miles than the preceding one. It was unlikely that they would arrive in Wellington that night.

Toward five o’clock in the afternoon, they could just make out the peaks of Ben More,15 to the south of the little port of Flaxbourne.16 It would take another five or six hours to reach the opening of Cook Strait. Since this passage runs from south to north, it would not be necessary to change the ship’s speed.

Flig Balt and Vin Mod were thus assured of having all night to accomplish their plans.

It goes without saying that the participation of Len Cannon and his comrades was settled. Sexton and Bryce, their drunkenness dissipated, and Kyle forewarned, had made no real protest. With Vin Mod supporting Len Cannon, they just waited for the right moment to move. Here were the conditions called for. The plan was as follows:

Between midnight and one o’clock, while the captain was asleep, Vin Mod and Len Cannon would penetrate into his cabin, gag him, carry him to the rail and throw him off into the sea before he had time to utter a cry. At the same time, Hobbes and Burnes, being on duty, would be seized by Kyle, Sexton, and Bryce and subjected to the same fate. That would leave Wickley on lookout; Koa and Flig Balt could easily subdue him, as well as the cabin boy. Once the plot was carried out, the only ones left on board would be the authors of the crime. There would not be a single witness, and the James Cook, at full sail, would soon reach the Pacific east of New Zealand.

All chances thus favored the success of this wretched plot. Before dawn, under the command of Flig Balt, the brig would be already far from these parts.

It was about seven o’clock when Cape Campbell17 was observed in the northeast. It was, properly speaking, the southernmost boundary of Cook Strait, matched by, at a distance of some fifty miles, Cape Palliser,18 the extremity of the isle of Ikana-Maoui.

The brig followed the coastline within less than two miles, all sails set, even the studding sail, for the breeze fell with the evening. The shore was clear, bordered with basaltic rocks, which form the foundation of the interior mountains. The crest of Mount Weld19 was visible like a point of fire under rays of the setting sun. Although the tides of the Pacific are of little importance, a current from the shore flowed northward and favored the progress of the James Cook toward the sea.

It was at eight o’clock that the captain would probably be in his cabin after having left the bosun on duty. They would only have to watch out for the passage of ships at the opening of the strait. Moreover, the night would be clear, and no sail appeared on the horizon.

Before eight, however, some smoke was sighted, astern and off the starboard side, and they were not long in seeing a steamer rounding Cape Campbell.

Vin Mod and Flig Balt were not put out. Surely, given its pace, it would soon have passed the brig.

It was a government mail carrier, which had not as yet shown its colors. Now at this instant a rifle shot was heard, and the British flag was unfurled from the yardarm.

Harry Gibson had stayed on the bridge. Was he going to remain there as long as the mail carrier was visible, whether it intended to cross the strait or head for Wellington?

That’s what Flig Balt and Vin Mod wondered, not without some concern and even a certain impatience, as they were so late being alone on the bridge.

An hour stretched by. Mr. Gibson, seated near the crew quarters, seemed disinclined to retire. He exchanged a few words with the helmsman Hobbes and watched the packet, which was now less than a mile from the brig.

Imagine how disappointed Flig Balt was, along with his accomplices, a disappointment bordering on rage. The English packet was moving at slow speed, and little steam puffed out of its exhaust. It rocked to the undulation of the long swell, barely troubling the water from the wash of the propeller, making no more wake than the James Cook.

Why had this ship slowed down so much? … Had some misfortune befallen the engine? Or was it simply a reluctance to enter the port of Wellington at night, where the channel offered so many difficulties? In any event, for one of those reasons, no doubt, it seemed to have decided to stay until dawn under low steam and, consequently, in view of the brig.

That was enough to frustrate Flig Balt, Vin Mod, and the others and to make them somewhat anxious as well.

Indeed, Len Cannon, Sexton, Kyle, and Bryce all thought at first that the packet had been sent from Dunedin in pursuit—that the police, having learned about their embarkment and their departure on the brig, were now seeking to recapture them. Exaggerated fears and certainly unfounded. It would have been simpler to send by telegraph the order to stop them as soon as they arrived in Wellington. One does not send a government ship to round up a few rowdy sailors, when it is easy to jail them in port.

Mr. Gibson exchanged a few words with the helmsman.

Len Cannon and his comrades were soon reassured. The packet made no signal to communicate with the brig, and put no tender in the water. The James Cook would not be the object of a search, and the recruits from the Three Magpies could rest at ease on board.

But if all fear was banished on this account, one can easily imagine the anger felt by Bosun Balt and Vin Mod. Impossible to act that night, and the next day the brig would be at its mooring in Wellington! Attacking Captain Gibson and three sailors could not be done in silence. They would resist, they would cry out, and their cries would be heard by the packet, which was but a few hundred yards away. The revolt could not begin in these conditions. It would have been quickly put down by the English vessel, which, in a few turns of the propeller, would have drawn alongside the ship.

“Damnation!” Vin Mod grumbled. “Nothing we can do about it! We’d risk being hoisted to the yardarm of this damned ship.”

“And tomorrow,” added Flig Balt, “the owner and Nat Gibson will be on board!”

If they had moved away from the packet, perhaps the bosun would have attempted it if the captain, instead of returning to his cabin, had not stayed the greater part of the night on the bridge. As it was, it was impossible to head out to sea. So, they had to temporarily abandon their plan to take over the brig.

The next day broke early. The James Cook passed Blenheim,20 situated on the shore of Tawaï-Pounamou on the east side of the strait; then it approached Point Nicholson, which juts out at the entrance to Wellington.21 Finally, at six o’clock in the morning, accompanied by the packet, it entered the port and moored in the middle of the harbor.

*Facsimile of an illustration published in the Great Voyages and Great Navigators by Jules Verne (Hetzel’s note).