Читать книгу The Kip Brothers - Jules Verne - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление7

The Two Brothers

At daybreak, a dense fog covered the western horizon. The rocky shore of Norfolk Island could barely be distinguished. No doubt those mists would soon dissipate. The peak of Mount Pitt rose above the fog and was already bathed in the sun’s rays.

Moreover, the shipwrecked men were probably not worried. Although the brig was no doubt invisible to them, had they not heard during the night its signals in response to their own? The boat could not have left its mooring, and in an hour its launch would be sent to shore.

Before lowering the launch, however, Mr. Gibson preferred to wait, and with good reason, for the outcropping of land to emerge from the mist. That was where the fire had been lit, and that is where the abandoned men who called upon the James Cook for help would be found. Obviously they did not possess even a dugout canoe, for otherwise they would already have come aboard.

The breeze from the southeast was beginning to stiffen. A few clouds, reclining on the line between sea and sky, indicated that the wind would freshen during the morning. Without the reason that held him to his anchor, Mr. Gibson would have given orders to set sail.

A little before seven o’clock, the foot of the coral reef, along which foamed a whitish surf, stood out under the fog. Curls of vapor rolled by, and the outcropping of land emerged.

Nat Gibson, on top of the officer’s quarters, his spyglass to his eye, ran it up and down the shore. He was the first to cry out:

“He’s there … or rather, they are there!”

“Several men?” asked the shipowner.

“Two, Mr. Hawkins.”

The latter took the spyglass in his turn:

“Yes,” he said, “and they’re signaling to us, shaking a piece of canvas on the end of a stick!”

The spyglass passed into the captain’s hands, who confirmed the presence of two individuals standing on the boulders at the very end of the promontory. The fog, dissolved by this time, permitted them to see the men, even with the naked eye. That there were two as Nat Gibson had believed he saw the evening before, there could no longer be any doubt.

“Lower the launch!” commanded the captain.

And at the same time, by his order, Flig Balt hoisted the British flag to the top of the spanker in response to the signals.

If Mr. Gibson had said to prepare the big dinghy for launch, it was in case there was need of taking on more than two people. It was possible, indeed, that other castaways had taken shelter on the island, especially if they belonged to the crew of the Wilhelmina. There was even reason to hope that all had reached that shore after having abandoned the schooner.

The craft settled into the water; the captain and his son took their places in it, the former at the helm. Four sailors sat at the oars. Vin Mod was among them, and just as he was slipping over the gunwale he had made a gesture to the bosun that indicated his irritation.

The launch headed for the coral reef. The day before, while fishing along the reef, Nat Gibson had noticed a narrow opening that permitted passage through it. There would only be a distance of seven or eight cable lengths from there to the point.

In less than a half hour the craft reached the opening. They noticed the last puffs of smoke from the remains of the fire that had been kept up all night and beside which the two men were standing.

From the bow of the craft, Vin Mod turned around impatiently to see them, so much so that he interfered with the movement of the oars.

“Watch out you don’t go for a swim, Mod!” the captain called out to him. “You’ll have time to satisfy your curiosity when we land.”

“Yeah, the time!” muttered the sailor, who, out of rage, would have broken his oar.

The channel wound through the coral banks that would have been dangerous to approach. Those sharp ridges, as cutting as steel, would have wreaked havoc on the hull of their craft. So Mr. Gibson ordered the sailors to slow their pace. There was no difficulty, anyway, in reaching the outermost point of the promontory. The water, responding to the breeze from the sea, pushed the craft forward. A fair surf was foaming at the base of the rocks.

The captain and his son watched the two men. Hand in hand, unmoving, silent, they made no gesture, nor did they call out. When the craft turned to round the point, Vin Mod could see them easily.

One was perhaps thirty-five years old, the other a bit younger. Dressed in tatters, head bare, nothing suggested they were mariners. About the same size, they resembled each other enough to be taken for brothers, blond hair, unkempt beards. In any case, they were not Polynesian natives.

And then, even before they could disembark, when the captain and his son were still seated on the rear thwart, the older advanced to the end of the point and in English, but with an accent, cried out: “Thank you for coming to our rescue … Thank you!”

“Who are you?” asked Mr. Gibson as soon as they had pulled up on shore.

“Two Hollanders.”

“Shipwrecked?”

“Yes, shipwrecked from the schooner Wilhelmina.”

“Are you the only survivors?”

“The only ones, or at least after the wreck the only ones who reached this coast …”

“Thank you for coming to our rescue!”

From the hesitant tones of these last words, it was clear that the man did not know whether he had found refuge on a continent or an island.

The grapnel was tossed ashore and when one of the sailors had set it in a hollow between the rocks, Mr. Gibson and his companions disembarked.

“Where are we?” asked the older man.

“On Norfolk Island,” replied the captain.

“Norfolk Island,” repeated the younger.

The shipwrecked men then understood where they were, on an isolated island in that section of the western Pacific. They alone were here, moreover, of all those passengers and crew that the Dutch schooner had aboard.

On the question of knowing what had happened to the Wilhelmina, if it had gone down with all hands, they could not give a definite answer to what Mr. Gibson was asking. As for the cause of the wreck, this is what they said:

Two weeks before, the schooner had been hit during the night—it must have been four or five miles east of Norfolk Island.

“Leaving our cabin,” the older of the two said, “we were dragged into a whirlwind. The night was dark and foggy … We caught hold of a chicken coop that was passing within our reach … Three hours later the current brought us to the coral reef, and we reached the island by swimming …”

“So,” asked Mr. Gibson, “you’ve been on the island for two weeks?”

“Two weeks.”

“And you didn’t meet anyone here?”

“No one.”

“And,” added the younger man, “we are fairly sure there is no other human being on this island, or at least this part of the shore is uninhabited.”

“It didn’t occur to you to search out the interior?” asked Nat Gibson.

“Yes,” replied the elder, “but it would have been necessary to venture into deep forests, at the risk of becoming lost, and we might not have found anything to eat there.”

“And then,” said the other, “what would we have gained, since you just told us we were on a desert island? It was better not to abandon the shore. That would have meant giving up any chance of being seen, or saved, as we have been.”

“You were right.”

“And your brig … What is it?” asked the younger man.

“The English brig, James Cook.”

“And its captain?”

“Myself,” responded Mr. Gibson.

“Well, Captain,” the older man said, shaking Mr. Gibson’s hand, “you can see that we were right in waiting for you on this promontory!”

Indeed, to go around the base of Mount Pitt, or even reach its peak, the shipwrecked men, experiencing insurmountable difficulties, would have perished from exhaustion and fatigue in the middle of the impassible forests of the interior.

“But how have you managed to survive in these conditions of privation?” asked Mr. Gibson.

“Our food consisted mainly of vegetation,” responded the older brother, “some roots here and there, cabbage palms cut from the tops of trees, wild sorrel, milkweed, sea fennel, pine cones of the araucaria. If we had had any line we could have caught fish, for they are numerous among the rocks.”

“And fire? …,” Nat Gibson asked, “How did you make it?”

“For the first days,” replied the younger, “we had to get along without it. No matches, or rather wet matches and quite useless. By good luck, while climbing toward the mountain behind us we found a volcanic fissure, still emitting some flames. Some layers of sulfur were around it, so we managed to cook our roots and vegetables.”

“So that’s how you’ve been living for two weeks?”

“That’s it, Captain. But I must admit, our strength was ebbing and we were desperate, when coming back yesterday from the fissure I noticed a ship anchored two miles from the coast.”

“The wind had given out,” said Mr. Gibson, “and since the current threatened to bear us southeast, I felt obliged to drop anchor.”

“It was already late,” said the elder. “There was scarcely an hour of daylight left and we were still more than half a league in the interior. After running as fast as possible toward the promontory, we noticed a dinghy setting off to join the brig … I called … With gestures I signaled for help …”

“I was in that dinghy,” Nat Gibson said, “and it seemed to me that I saw a man—just one—on that rock, at the moment dusk was moving in.”

“That was me,” said the elder. “I had arrived before my brother … and what disappointment I felt when the dinghy moved off without my being noticed! We thought that the last chance of salvation was slipping away! A little breeze came up. Wouldn’t the brig move on during the night? The next day wouldn’t it be far out on the high sea again?”

“Poor fellows!” murmured Mr. Gibson.

“The shore was plunged into darkness. We could see nothing of the ship. The hours slipped by … It was then that we thought of lighting a fire on the promontory. Dried grasses, dry wood, we brought it by the armfuls and some hot coals from the fire that we kept alive on this shore. Soon we had a good fire going. If the ship was still at its mooring, the fire would surely be seen by the men on watch … Oh! what a joy when about ten o’clock we heard those three shots fired! Then a lantern was burning at the top of the brig’s mast … They had seen us! We were sure now that the ship would wait until daybreak before leaving, and we would be rescued after dawn … But it was in time, Captain, yes! Your arrival was in time, and, as I said when you first came ashore, thank you … thank you …”

The shipwrecked men seemed near the end of their tether. Insufficient food, exhaustion, complete misery under the tatters that scarcely covered them … One could readily understand that they were anxious to be aboard the James Cook.

“Come aboard,” said Mr. Gibson. “You need food and clothing. Then we’ll see what we can do for you.”

The survivors of the Wilhelmina had no need to return to shore. Their rescuers would furnish them every need. They would not have to set foot on the island again!

As soon as Mr. Gibson, his son, and the two brothers had seated themselves in the stern, the grapnel was taken in and the craft started back through the channel.

Mr. Gibson had observed, in listening to the way they expressed themselves, that these two men were of a class well above that from which sailors are generally recruited. However, he had wanted to wait until they were in the presence of Mr. Hawkins to learn of their situation.

For his part and to his bitter displeasure, Vin Mod had also recognized that the rescued men did not represent run-of-the-mill seamen like Len Cannon and his comrades from Dunedin, or even those adventurers whom one encounters all too frequently in this part of the Pacific.

The two brothers were not at all part of the schooner’s crew. They were passengers, then, and probably the only ones who got out of that sinking ship safe and sound. So Vin Mod returned even more irritated by the thought that his plans would not be carried out.

The craft came alongside. Mr. Gibson, his son, and the shipwreck victims climbed to the bridge. The latter two were presented to Mr. Hawkins, who did not conceal his emotions on seeing what a miserable state they were in.

After shaking hands, he said:

“You’re welcome here, my friends.”

The two brothers, no less impressed, were about to throw themselves at his knees, but he stopped them.

“No,” he said, “no … we are most happy …”

A good-hearted man, he was at a loss for words, and he could only second the words of Nat Gibson, who called out:

“Let’s eat. Let’s give them something to eat. They’re dying of hunger!”

The two brothers were led to the mess, where their first meal was served, and there they could catch up after two weeks of privation and suffering.

Then Mr. Gibson put at their disposal one of the side cabins, where some clothes, selected from the crew’s spare garments, were set out. Then, once cleaned and dressed, they returned aft and in the presence of Mr. Hawkins, of the captain and his son, they recounted their story.

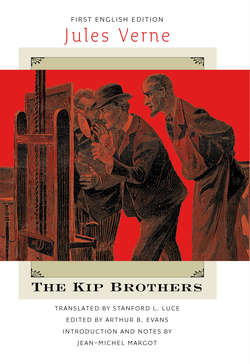

These men were Dutch, originally from Groningen. Their names were Karl and Pieter Kip.1 The elder brother, an officer in the Netherlands merchant marine, had made a number of crossings as lieutenant, then second in command of commercial ships. Pieter, the younger, was associated with an office in Ambon, on one of the Molucca Islands of Indonesia,2 an affiliate of the Kip Company of Groningen.

This firm carried out wholesale and semi-wholesale commerce in the archipelago, which belongs to Holland, and more specifically in the trade of nutmegs and cloves, very abundant in this Spice Island colony. If the above-named company did not count among the most important of the city, at least its head enjoyed an excellent reputation in the commercial world.

Mr. Kip Senior, widower for several years, had died five months before. This was a serious loss for the business, and efforts were made to prevent a liquidation that would have been carried out under unfavorable conditions. It was especially necessary for the two brothers to return to Groningen.

Karl Kip was thirty-five years old.3 A good sailor, about to be appointed captain, he was awaiting his promotion and would not be long in obtaining it. Perhaps of a less acute intelligence than his brother, or less of a businessman, less appropriate for directing a commercial firm, he exceeded him in resolve as well as in strength and physical endurance. His greatest disappointment stemmed from the fact that the Kip Company’s financial situation did not permit him to own a ship. Karl Kip would have liked to run his own business of long-distance navigation and trade. But it would have been impossible to divert any funds from the commercial side of the firm, and the elder son’s desire had never been fulfilled.

Karl and Pieter were united in a bond of friendship that no discord had ever diminished, even more deeply linked by affection than by blood.4 Between the siblings, there was no ill feeling, no cloud of jealousy or rivalry. Each remained in his own sphere. The one had his long-range voyages, the emotions and dangers of the sea. The other had his work at the Ambon office and his connection with Groningen. Their family sufficed for them. Neither had ever sought to create a second one, creating new bonds that might have separated them. It was already more than enough that the father was in Holland, Karl navigating at sea, Pieter in the Moluccas. As for the latter, intelligent, having a commercial acumen, he dedicated himself entirely to the business. His associate, also Dutch, applied himself to developing their enterprise. He was confident about increasing the growth of the Kip Company, sparing neither his time nor his zeal.

When Mr. Kip passed away, Karl was in the port of Ambon, aboard a Dutch three-master from Rotterdam, on which he was serving as second in command. The two brothers were grievously stricken by this blow, which deprived them of a father for whom they had a deep affection. And they had not been there to hear his last words, his last sigh!

The two brothers then made this resolution: Pieter would leave the Ambon association and would return to Groningen to direct his father’s business.

But at this time the three-master, Maximus, on which Karl Kip had come to the Moluccas—already old and in poor repair—was declared unfit for the return home. Severely damaged by foul weather during its crossing from Holland, it could only be demolished. So its captain, its officers, and its sailors were to be repatriated to Europe under the charge of the Hopper firm, of Rotterdam, to which it belonged.

Now this repatriation would require, no doubt, a fairly long stopover in Ambon if the crew had to wait for some ship bound for Europe, and the two brothers were in haste to return to Groningen.

So Karl and Pieter Kip decided to take passage on the first boat leaving, either from Ambon, or from Ceram, or from Ternate, other islands in the Moluccan archipelago.

At that time the three-masted schooner Wilhelmina arrived from Rotterdam, but it had only a short stopover. It was a ship of some five hundred tons, which was going to return to its home post, stopping at Wellington, from where its commander, Captain Roebok,5 would set sail to reach the Atlantic by rounding Cape Horn.

If the position of the second in command had not been filled, there was no doubt that Karl Kip might have obtained it. But the crew was complete, and not one of the Maximus sailors could be hired. Karl Kip, not wishing to miss a chance, reserved a passenger cabin on the Wilhelmina.

The three-master put out to sea September 23rd. Its crew included the captain, Mr. Roebok; the second in command, Stourn; two bosuns; and ten sailors, all Dutch by nationality.

The navigation was quite smooth on the stretch across the Arafura Sea,6 so narrowly squeezed in between the northern coast of Australia, the south coast of New Guinea, and the group of Sula Islands,7 to the west, which protect it from the heavy swell of the Indian Ocean. To the east, it offers no way out but the Torres Strait, terminated by Cape York.8

After entering this strait, the ship encountered headwinds, which stalled it for a few days. It was not until October 6th that it managed to wind its way through the numerous reefs and enter the Coral Sea.9

Facing the Wilhelmina lay the vast Pacific as far as Cape Horn, which they would pass after a stopover in Wellington, New Zealand. The route was long, but the Kip brothers had no choice.

On the night of the 19th and 20th of October, all was going well on board, with sailors on watch in the forward part of the ship, when a dreadful accident occurred that the most vigilant watch could not have avoided.

Heavy, dark fog enveloped the sea, absolutely calm, as it almost always is during these atmospheric conditions.

The Wilhelmina carried the standard lights, green on the starboard, red on the port side. But unfortunately they would not have been seen through that thick fog, even at a distance of half a cable.

Suddenly, without any siren being heard, without any lantern being seen, the three-master was struck on the windward side at the height of the crew’s quarters. The frightful shock immediately toppled the mainmast and the mizzenmast.

At the moment when Karl and Pieter Kip rushed from the poop deck, they glimpsed only an enormous mass vomiting smoke and steam, which passed like a bomb after having cut the Wilhelmina in half.

For a half a second a white flame had appeared at the mainstay of the ship. It was a steamer, but that was all they were to know about it.

The Wilhelmina, bow on one side, stern on the other, sank immediately. The two passengers did not have time to rejoin the crew. They could scarcely see a few sailors tangled among the ropes. To use the lifeboats was impossible, for they were submerged. As for the second in command and the captain, no doubt they had been unable to leave their cabins.

The two brothers, half dressed, were already in the water up to their waists. They felt the remains of the Wilhelmina being sucked down into the sea and being dragged into the vortex that swirled about the ship.

“Let’s not get separated!” shouted Pieter.

“Count on me!” replied Karl.

Both were good swimmers. But was there any land nearby? What was the three-master’s position at the moment of collision in this part of the Pacific between Australia and New Zealand, below New Caledonia, which was observed toward the east forty-eight hours before, in the last ship’s log entry of Captain Roebok?

It goes without saying that the colliding steamer was probably far away already, unless it had stopped after the shock. If they had put lifeboats to sea, how, in the middle of a fog, would they find the survivors of this catastrophe?

Karl and Pieter thought they were lost. A profound darkness enveloped the sea. No whistle of machinery or siren indicated the presence of a ship, nor the howl that escaping steam would have emitted if it had remained in the area where the accident occurred. Not a single piece of wreckage was within reach of the two brothers.

For half an hour they tried to support each other, the older brother encouraging the younger, lending him the support of his arm when the younger grew weaker. But the moment approached when both would be at the end of their resources, and after one last clasp, one ultimate good-bye, they would slip down into the abyss …

It was around three in the morning when Karl Kip managed to seize an object floating near him. It was one of the chicken cages from the Wilhelmina.10 They both grabbed onto it.

Dawn finally pierced the yellowish banks of fog. The mist was not long in rising and a clapping of little waves began as the breeze blew harder.

Karl Kip turned his eye toward the horizon.

To the east, an empty sea. In the west there was a fairly high slope of land—that is what he was finally able to see.

That shore was less than three miles away. The current and the wind were going in that direction. There was every hope of reaching it, if the swell of the sea did not grow too strong.

Whatever type of land it was, island or continent, this coast assured the shipwrecked men a means of salvation.

The shore, stretching out to the west, was dominated by a peak, which the first rays of sunlight gilded at the very top.

“There! … There!” Karl Kip cried out.

There, indeed, for at sea they would have searched in vain for a sail or lanterns of a ship. No vestige of the Wilhelmina remained. It had been lost, with all hands and all cargo. Nor was there any sight of the fateful steamer, which, more fortunate no doubt in having survived the collision, was now out of sight.

Lifting himself up a bit, Karl Kip could perceive no debris of the hull or of the masts. The only surviving evidence was the chicken cage that they were clinging to.

Exhausted and stiff, Pieter would have slipped into the deep if his brother had not kept his head above water. Vigorously now, Karl swam on, pushing the cage toward a barely perceptible reef, where the surf whitened its irregular line.

This first fringe of the coral ring stretched out from the coast. It took a full hour to reach it. With the swell that swept them along, it would have been difficult to gain a footing. The shipwrecked men slipped through a narrow channel, and it was a little more than seven o’clock when they managed to pull themselves onto the outcropping of land where the dinghy from the James Cook had just rescued them.

It was on that unknown, uninhabited island that the two brothers, barely clad, with no tools, no instruments, no utensils, were going to spend fifteen days of a most miserable existence.

Such was the tale that Pieter Kip recounted, while his brother, listening in silence, confirmed it only with a nod.

It was now known why the Wilhelmina, long awaited in Wellington, would never arrive, and why the French ship Assumption had not found a wreck along its way. The three-master lay in the depths of the sea, unless the currents had brought some debris further north.