Читать книгу The Kip Brothers - Jules Verne - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

At Wellington

The city of Wellington is built on the southwest point of North Island at the far side of a horseshoe-shaped bay. Well protected from the sea winds, it offers excellent moorings. The brig had been favored by the weather, but such was not always the case. It was often difficult to navigate in Cook Strait, which is crossed by currents whose speed sometimes reaches ten knots, even though the tides in the Pacific are never strong. The seafarer Tasman,1 to whom is credited the first discovery of New Zealand in December 1642, ran great risks of running aground and then being attacked by the natives. Hence the name “Bay of the Massacre,”2 which figures in the geographic nomenclature of the straits. The Dutch navigator lost four of his men who were devoured by cannibals on that shore, and, a hundred years later, the English navigator, James Cook, left in their hands the crew of one of the ships in his fleet, commanded by Captain Furneaux.3 Finally, two years later, the French navigator Marion Dufresne4 and sixteen of his men met their death in an attack of the most frightful savagery.

In 1840, in the month of March, Dumont d’Urville,5 aboard Astrolabe and Zélée, passed by Otago Bay of the southern island and visited the Snare Islands and Stewart Island at the southern end of Tawaï-Pounamou. Then he sojourned in the port of Akaroa, where he had no need to complain about the natives. The memory of this illustrious explorer’s passage is marked by the island that bears his name. Inhabited only by bands of penguins and albatrosses, it is separated from South Island by the “French Pass,” where the sea is so treacherous that ships do not voluntarily enter into its channel.6

Today, under the authority of the British flag, at least as far as the Maoris are concerned, every security is assured in the latitudes of New Zealand. The dangers that were of human origin have been warded off. Only those in the sea continue, and even so, they are of a lesser sort, thanks to the hydrographic maps of the area and to the establishment of the gigantic lighthouse built on an isolated rock in front of the Nicholson Bay,7 where Wellington is located.

It was in the month of January 1849 that the New Zealand Land Company sent the Aurora to establish settlers on the shores of these distant lands. The population of the two islands counts no less than eight hundred thousand inhabitants, and Wellington, the capital of the colony, is itself home to some thirty thousand.

The city is pleasantly situated, solidly constructed, and has broad streets that are properly maintained. Most of the houses are built of wood (for earthquakes are frequent in the southern province) as are the public structures, among others the governmental palace in the middle of its beautiful park and the cathedral, whose religious character does not exempt it from such earthly cataclysms.8 This city, less important, less industrial, and less commercial than its two or three rivals in New Zealand, will equal them someday no doubt, given the drive and colonizing genius of Great Britain. In any case, with its University, its Legislative House composed of fifty-four members, among them four Maoris named by the governor, its House of Representatives coming directly from popular suffrage, its colleges, its schools, its museum, its productive factories for frozen meats, its model prison, its squares, and its public gardens, where electricity is going to replace gas, Wellington boasts an exceptional standard of living, which many cities in the Old and the New World might envy.

If the James Cook did not tie up at the dock, it was because Captain Gibson wanted to make it more difficult for the men to desert.9 Gold fever exerted its influence here as it did in Dunedin or in the other New Zealand ports. Several ships found it impossible to cast off. Mr. Gibson wanted to take every precaution to maintain his crew at full strength, even those recruits from the Three Magpies whom he would willingly exchange for others. Besides, his stopover in Wellington would be of short duration, scarcely twenty-four hours.

The first people to receive him on his visit were Mr. Hawkins and Nat Gibson. The captain had been brought ashore as soon as he arrived in port, and eight bells were striking when he presented himself at Mr. Hawkins’s office, situated at the far end of one of the streets that ran down to the port.

Wellington (photo: J. Valentine & Sons, Dundee)

“Father!”

“My friend!”

Thus was Harry Gibson greeted when he entered the office. He had arrived before the departure of his son and Mr. Hawkins, who were getting ready to go down to the dock, as they did each morning, to see if the James Cook might not be finally sighted by the semaphore lookout.

The young man flung his arms around his father’s neck, and the shipowner hugged the latter in his arms.

Mr. Hawkins,10 now fifty years old, was a man of middle stature, graying hair, no beard, bright and friendly eyes, good health and constitution, very nimble, active, knowledgeable in commerce, and bold in business. It was known that his business in Hobart Town was very successful, and he could have retired already with his fortune made. But it would not have suited him, after such a busy career, to live in idleness. So, with the goal of developing his fleet, which included several other ships, he had come to Wellington to set up an office with an associate, Mr. Balfour. Nat Gibson would become the principal employee and profit-sharer as soon as the James Cook had completed its voyage.

Captain Gibson’s son, then twenty-one years old, had a lively intelligence, a serious turn of mind, and a deep affection for his mother as well as for Mr. Hawkins. It is true, the latter and the captain were so closely attached in his filial devotion that Nat Gibson could hardly distinguish between them. Ardent, enthusiastic, a lover of beautiful things, Nat was an artist who also had some talent for business affairs. His height was greater than average, his eyes dark, his hair and beard chestnut, his gait elegant, his attitude composed, his countenance friendly. He made a good impression straight off, and he had only friends. On the other hand, there was no doubt but that he would become, with age, resolute and energetic. With a firmer temperament than his father, he took after his mother.

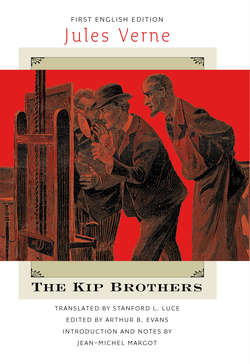

Mr. Hawkins and Captain Gibson

In his leisure time, Nat Gibson dabbled with great pleasure in photography,11 this art that had made much progress thanks to the use of accelerating substances, which bring the snapshots to the utmost degree of perfection. His camera was always in his hand, and one can imagine how he had already made good use of it during this trip: picturesque sites, portraits of natives, photographs of all sorts.

During his stay in Wellington, he had shot a number of views of the city and its environs. Mr. Hawkins himself took an interest in it. They were both often seen setting off, with their camera supplies strapped bandolier-style across their bodies, and returning from their excursions with new riches for their collection.

After having presented the captain to Mr. Balfour, Mr. Hawkins returned to his office, with Mr. Gibson and his son following him. And there, at first, they talked about Hobart Town. News was not lacking, thanks to the regular service between Tasmania and New Zealand. Just the day before, a letter from Mrs. Hawkins had arrived, and the ones from Mrs. Gibson had been awaiting the arrival of the James Cook in Wellington for several days.

The captain read his correspondence. Everything was fine at home. The women were in good health. It is true, the absence seemed long to them, and it was their hope that it would not be prolonged. But the voyage should soon be drawing to a close.

“Yes,” said Mr. Hawkins, “five or six weeks more and we’ll be back in Hobart Town.”

“Dear mother,” Nat Gibson exclaimed, “how happy she will be to see us again, just as much as we were, Father, in embracing you!”

“And that I was, myself, my son!”

“My friend,” said Mr. Hawkins, “I have every reason to believe that the voyage of the James Cook will be of short length.”

“That’s what I think too, Hawkins.”

“Even at average speed,” replied the shipowner, “the voyage from New Zealand to New Ireland12 is fairly short.”

“In this season especially,” answered the captain. “The sea is calm all the way to the equator, and the winds are steady. I think as you do that we’ll have no delays to put up with if our stopover in Port Praslin13 doesn’t have to be prolonged.”

“That won’t be the case, Gibson. I’ve received a letter from our correspondent, Mr. Zieger, that is very reassuring on this subject. In the archipelago, there is a large stock of merchandise of mother of pearl and copra, and loading the brig can be done without difficulty.”

“Is Mr. Zieger ready to take delivery of our merchandise?” asked the captain.

“Yes, my friend, and I repeat, I have been assured that there will be no delay on his end.”

“Don’t forget, Hawkins, that after Port Praslin, we’ll have to go to Kerawara.”14

“That will be only a day, Gibson.”

“Well, Father, let’s be clear on the length of the voyage. How many days will our stopover at Port Praslin and Kerawara be?”

“About three weeks in all.”

“And from Wellington to Port Praslin?”

“About the same.”

“And the return to Tasmania?”

“About a month.”

“So in two months and a half, it’s possible that the James Cook will be back in Hobart Town.”

“Yes. Rather less time than more.”

“Good,” Nat Gibson replied. “I’m going to write to my mother this very day, because the courier to Australia raises anchor the day after tomorrow. I will ask her for two and a half months of patience. That’s how much Mrs. Hawkins will have to have too, isn’t that right, Mr. Hawkins?”

“Yes, indeed, my young man.”

“And at the beginning of the year, the two families will be reunited.”

“Two families will be as one!” replied Mr. Hawkins.

The shipowner and the captain shook hands affectionately.

“My dear Gibson,” Mr. Hawkins then said. “We’ll have dinner here with Mr. Balfour.”

“Of course, Hawkins.”

“Do you have business to take care of downtown?”

“No,” replied the captain, “but I must return on board.”

“Fine, then on to the James Cook!” exclaimed Nat Gibson. “It will give me great pleasure to see our brig again before bringing up our bags.”

“Oh!” replied Mr. Hawkins. “It’s surely going to stay a few days in Wellington?”

“Twenty-four hours at most,” replied the captain. “I have no breakdowns to fix, no cargo to take off or bring on … Some provisions to renew, for sure, and an afternoon will suffice for that. I’ll give orders to Balt to take care of this.”

“Are you still happy with your bosun?” asked Mr. Hawkins.

“Still am,” Captain Gibson replied. “He’s a zealous man who knows his job.”

“And the crew?”

“Veteran sailors, nothing to fault them for.”

“What about those you picked up in Dunedin?”

“They don’t inspire much confidence, but I couldn’t find any better.”

“So the James Cook is leaving?”

“As of tomorrow, if we don’t have any incidents like at Dunedin. Nowadays it’s not too good for captains of commerce to make port in New Zealand.”

“You’re talking about desertions that diminish the crews?” asked Mr. Hawkins.

Mr. Gibson replied, “More than diminish; out of eight sailors, I have lost four and haven’t heard a word from them.”

“Well, you’re right, Gibson, be careful that the situation doesn’t get to be in Wellington what it was in Dunedin.”

“So I have taken the precaution of not allowing anyone to disembark under any pretext, even Koa the cook.”

“That’s wise, father,” added Nat Gibson. “There are a half-dozen ships in port that cannot set sail for lack of sailors.”

“That doesn’t surprise me,” replied Harry Gibson. “So I’m counting on raising sail as soon as we have brought on the provisions, and surely by dawn we’ll have weighed anchor and already be on our way.”

At the very moment when the captain pronounced the name of the bosun, Mr. Hawkins had been unable to keep from making a rather pointed observation.

“If I spoke to you about Flig Balt,” he continued, “it’s because he didn’t make a very favorable impression on me when we hired him on at Hobart Town.”

“Yes, I know,” replied the captain, “but your misgivings are not warranted. He carries out his duties with zeal, the men know they have to follow him, and, I’ll say it again, his service aboard ship has left nothing to be desired.”

“So much the better, Gibson. I prefer to have made a mistake about him, and so long as he inspires confidence in you …”

“Besides, Hawkins, when it’s a question of making command decisions aboard the ship, I depend on myself alone; for the rest, as you know, I willingly leave that to my bosun. Since our departure, I have had nothing to reproach him for if he wants to get back on the brig for his next trip …”

“That’s your business, after all, dear friend,” replied Mr. Hawkins. “You’re a better judge of what measures to take.”

It was clear that the confidence that Flig Balt inspired in Harry Gibson, an ill-placed confidence, was total, so well had this treacherous rogue played his role. That’s why, when Mr. Hawkins asked again if the captain was sure about the four seamen who had not deserted ship, the latter replied:

“Vin Mod, Hobbes, Wickley, and Burnes are good sailors,” he replied, “and what they didn’t do in Dunedin, they wouldn’t attempt to do here.”

“We’ll settle up with them when we get back,” declared the shipowner.

“So,” continued the captain, “they’re not the reason I forbade the crew to come ashore … it’s because of the four recruits.”

And Mr. Gibson explained under what conditions Len Cannon, Sexton, Kyle and Bryce had signed on, out of their haste to escape the Dunedin police, after a fight in the tavern of the Three Magpies.

“So this was the most practical thing to do?” asked the shipowner.

“Assuredly, my friend. You know how hard pressed I was by this delay of two weeks. I was at the point of wondering whether I might not have to wait months to fill out the crew! What do you expect? You take what you can find!”

“And we part company with them as soon as possible,” replied Mr. Hawkins.

“Just as you say, Hawkins. That’s even what I would have done here, in Wellington, if circumstances had allowed it, and that’s what I’ll do in Hobart Town.”

“We have time to think about it, Father!” Nat Gibson observed. “The brig will stay several months laid up, won’t it, Mr. Hawkins? And we will spend this time as a family until the day I return to Wellington.”

“That will all be arranged, Nat,” replied the shipowner.

Mr. Hawkins, Mr. Gibson, and his son left the office, went down to the dock, hailed one of the small boats employed by the port service, and were brought out to the brig.

It was the bosun who welcomed them on board, as obsequious as ever, always busy, and for whom Mr. Hawkins, reassured by the captain’s declarations, saved his good greetings.

“I see you’re in good health, Mr. Hawkins,” Flig Balt said to him.

“In good health, I thank you,” replied the shipowner.

The three sailors, Hobbes, Wickley and Burnes, who had sailed for some three years aboard the James Cook without having given any cause for complaint, received Mr. Hawkins’s compliments.

As for Jim, the shipowner kissed him on both cheeks, and the young man felt a great joy in seeing him again.

“I have excellent news from your mother,” Mr. Hawkins told him, “and she really hopes that the captain is satisfied with you.”

“Entirely,” declared Mr. Gibson.

“I thank you, Mr. Hawkins,” said Jim, “and you make me very happy!”

“And me?” said Nat Gibson. “There’s nothing for me?”

“Why, of course, Mr. Nat,” replied Jim, throwing his arms around his neck.

“And what a nice healthy appearance you have!” added Nat. “If your mother saw you, she’d be content, the fine woman! Also, Jim, I’ll take your photograph before leaving.”

“It’ll look like me?”

“Of course, if you don’t move.”

“I won’t move, Mr. Nat, I won’t move!”

It must be said that Mr. Hawkins, after having spoken to Hobbes, Wickley and Burnes about their families who lived in Hobart Town, addressed a few words to Vin Mod. The latter showed he was quite sensitive about this attention. It is true, the shipowner knew him less than his comrades, and it was his first trip on board the James Cook.

As for the recruits, Mr. Hawkins simply greeted them with a “Good day.”

There is reason to admit that their demeanor did not make a better impression on him than on Mr. Gibson. They could have, however, with no trouble, been permitted to go ashore. They would not have had the idea of deserting after forty-eight hours of navigation, and they would certainly have returned before the departure of the brig. Vin Mod had worked them over well, and despite the presence of Mr. Hawkins and Nat Gibson, they were quite sure that some occasion would present itself to take over the ship. It would be a bit more difficult. But what is impossible to people who have no faith, no law, and are determined not to back down from any crime?

After an hour, during which Mr. Hawkins and Mr. Gibson examined the books of the trip, the captain announced that the brig would put to sea the next day at dawn. The shipowner and Nat Gibson would return that evening to take possession of their cabin, to which they had already sent their baggage.

However, before getting back to the dock, Mr. Gibson asked Flig Balt if he had no reason to return to land:

“No, Captain,” replied the bosun. “I prefer to remain on board. It’s wiser to keep an eye on the crew.”

“You’re right, Balt,” said Mr. Gibson. “Anyway, the cook will have to go pick up the provisions.”

“I’ll send him, Captain, and if needed, two men with him.”

All was agreed upon, and the dinghy that had brought the shipowner and his two companions brought them back to the dock. From there they returned to the office, where Mr. Balfour was waiting. He joined them for lunch.

During the meal, they discussed business. Up to now, the voyages of the James Cook had been among the most lucrative, and it was showing good profits.

The great coastline trade had, indeed, developed remarkably well in this part of the Pacific. Germany, having taken possession of the neighboring archipelagoes of New Guinea, had opened up new opportunities for trade.15 It was not without reason that Mr. Hawkins had established relations with Mr. Zieger, his correspondent from New Ireland, now Neu-Mecklenburg. The office that he had founded in Wellington was meant especially to build these relations through the attention of Mr. Balfour and Nat Gibson, who would be installed next to him in a few months.

Lunch out of the way, Mr. Gibson wanted to take care of the provisions for the brig that the cook could pick up that afternoon: canned goods, fowl, pork, flour, dry beans, cheeses, beer, gin and sherry, coffee and spices of various sorts.

“Father, you can’t leave until I’ve taken your picture!” declared Nat.

“Not again,” called out the captain.

“There, old friend,” Mr. Hawkins added, “we are both obsessed with the demon of photography, and we give people no rest until they pose in front of our lens. So you have to submit gracefully!”

“But I already have two or three portraits at home, in Hobart Town!”

“Fine, this’ll make one more,” replied Nat Gibson. “And since we leave tomorrow, Mr. Balfour will take charge of sending it to mother in the next mail.”

“Agreed,” Mr. Balfour said.

“See, Father,” resumed the young man, “a portrait is like a fish! It has no value unless it’s fresh! Just think, now you are ten months older than when you left Hobart Town, and I’m sure you don’t look like your last photograph, the one over the fireplace of your room.”

“Nat is right,” confirmed Mr. Hawkins, laughing. “I barely recognized you this morning!”

“For heaven’s sake!” Mr. Gibson exclaimed.

“No, I assure you! There’s nothing that changes you more than ten months of navigation at sea!”

“Go ahead, my child,” replied the captain, “here I am ready for the sacrifice.”

“And what attitude are you going to take?” asked the shipowner in a pleasant tone. “That of the sailor departing or of the sailor arriving? Will it be the commander’s posture, his arm extended toward the horizon, his hand holding the sextant or the telescope, or the pose of the master second only to God?”

“Either one you want, Hawkins.”

“And then, while you’re posing in front of our camera, try to think of something! That gives more expression to your face! What will you be thinking about?”

“I’ll be thinking of my dear wife,” answered Mr. Gibson, “of my son … and of you … my friend.”

“So, we’d have a magnificent print.”

Nat Gibson owned one of those portable cameras, top of the line, that produce the negative in a few seconds. Mr. Gibson’s photo was very successful, so it seems, according to what his son said when he had examined the negative, and the print would be left in the care of Mr. Balfour.16

Mr. Hawkins, the captain, and Nat then left the office in order to buy everything needed for a voyage of nine or ten weeks. Warehouses are not scarce in Wellington, and one can find diverse maritime supplies: foodstuffs, sea instruments, tackle, pulleys, ropes, spare sails, fishing equipment, barrels of grease and tar, caulking and carpenter’s tools. But except for replacing a few ropes and chains, the needs of the brig were limited to that of food for the passengers and crew. This was quickly bought, paid for, then sent to the James Cook, as soon as the sailors Wickley and Hobbes and the head cook had arrived.

At the same time, Mr. Gibson completed the formalities that are obligatory for every ship upon entry and departure. Therefore, nothing would prevent the brig from weighing anchor, more fortunate than several other ships of commerce whose crew desertions held them in port at Wellington.

New Zealand dug-out canoes*

Maoris (photo: J. Valentine & Sons, Dundee)

During his trips across the city, in the midst of a very busy populace, Mr. Hawkins and his companions met a certain number of Maoris from the surrounding region.17 Their numerical importance has diminished greatly in New Zealand, like Australians in Australia, and above all Tasmanians in Tasmania, since the last specimens of this latter race have practically disappeared.

They number today but some forty natives on the northern island and scarcely two thousand on the southern one. These Maoris keep busy mostly with market gardening, principally with the cultivation of fruit trees, whose products are very abundant and of excellent quality.

The men are a handsome sort and boast an energetic character and a constitution that is both robust and healthy. In comparison, the women seem inferior. In any case, one must get used to seeing this “weaker” sex walk the streets, pipe in mouth and smoking more than the “strong” sex. It is also not surprising that the exchange of civilities with Maori women is very difficult since, according to custom, it is not just a question of saying “hello” or of shaking hands, but of rubbing noses.

These natives are, so it seems, of Polynesian origin, and it is even possible that the first immigrants into New Zealand came from the archipelago of Tonga-Tabou,18 which is situated some twelve hundred miles to the north.

There are, basically, two reasons that this population is decreasing rapidly and destined to disappear in the future. The first cause is illness, especially pulmonary phthisis, which wreaks great devastation among Maori families. The second, still more terrible, is drunkenness, and it is to be noted that Maori women are first in rank in this dreadful abuse of alcoholic liquors.

In addition, there is reason to believe that the Maoris’ eating habits have been profoundly modified. Thanks to the missionaries, the influence of Christianity has become dominant. The natives were cannibalistic in days gone by,19 and who would dare say that such ultra-nitrogenous food did not suit their temperament? Be that as it may, it’s better that they disappear rather than eat each other, “although,” as a very observant tourist once said, “cannibalism never had but one goal, battle: devouring the eyes and heart of the enemy in order to become inspired by his courage and to acquire his wisdom!”

Maori arms and musical instruments*

These Maoris resisted British invasion until 1875; it is at that time when the last Maori leader of the King Country region surrendered to the authority of Great Britain.

Around six o’clock, Mr. Hawkins, the captain, and Nat Gibson returned to the office for dinner. Then, after saying goodbye to Mr. Balfour, they had themselves brought to the brig, which would be ready to hoist anchor at the first glimmer of dawn.

*Facsimile of an illustration published in the Great Voyages and Great Navigators by Jules Verne (Hetzel’s note).

*Facsimile of an illustration published in the Great Voyages and Great Navigators by Jules Verne (Hetzel’s note).