Читать книгу The Kip Brothers - Jules Verne - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

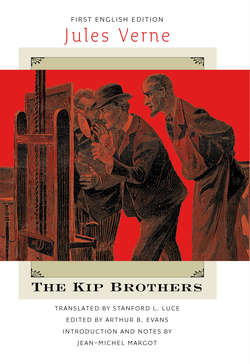

Les Frères Kip (The Kip Brothers) is one of those rare Jules Verne novels originally published as part of his Voyages extraordinaires that has, until now, never been translated into English.1 Why? Some Verne scholars have suggested that British and American publishers refused to translate these works for political and ideological reasons, reacting to the growing number of anti-British and anti-American passages in them.2 In the case of The Kip Brothers, however, the reason was more likely commercial. Since it did not conform to the Anglo-American stereotype of what a Jules Verne novel should be about (i.e., a Victorian sci-fi tale with intrepid heroes exploring the far-flung corners of the world and beyond, often with the aid of advanced technology), its market potential was probably deemed too low to justify the costs of translating and publishing. Otherwise, these same publishers would have no doubt opted to do what they had done for so many earlier English-language editions of Verne’s works—that is, simply delete or rewrite the offending passages in question.3 It is interesting to note that, even in its original French edition, The Kip Brothers is quite rare. In the words of a contemporary biographer of Verne, it “is among the least likely of all the books in the Verne cycle to be found today, for it was seldom, if ever, reprinted.”4

It is therefore fair to say that The Kip Brothers represents a unique novel in Verne’s oeuvre. Written soon after the death of his brother Paul, it celebrates more than any other the fraternal bonds of brotherhood. As a detective story that foregrounds themes of vision and perception, it resonates with Verne’s own life as he struggled with his progressive loss of eyesight from cataracts. And finally, published during a time when the Dreyfus Affair was deeply perturbing and polarizing French society, it offers a strangely similar story of judicial error and social injustice.

COMPOSITION AND PUBLISHING HISTORY

In January 1902, Jules Verne’s new novel The Kip Brothers began to appear in serial format in the popular French periodical Magasin d’Education et de Récréation. Episodes of the story continued to be published throughout 1902, concluding in the December issue of that year.

The Magasin d’Education et de Récréation was founded on March 20, 1864, by Pierre-Jules Hetzel, with a new issue appearing every two weeks. Quite successful, the journal offered an entertaining blend of fiction and nonfiction, and one of its educational goals was to teach geography and science to middle-class French families. Hetzel himself was arguably one of the most important book publishers in France during the nineteenth century.5 And Jules Verne was, for more than fifty years, Hetzel’s star writer. As a rule, most of Jules Verne’s novels were first published as serials in Hetzel’s Magasin d’Education et de Récréation.6

Exactly when Verne wrote The Kip Brothers has been the subject of some debate over the years. Many—including Christian Porcq—have traditionally assumed that it was during 1901,7 whereas Olivier Dumas has argued for a much earlier date, 1898.8 And the question of whether or not Verne’s son, Michel, had a hand in the composition of this novel (as he did in most of Verne’s posthumous works) has also been raised. To set the record straight, The Kip Brothers is among those last novels of the Voyages extraordinaires to be written wholly by Jules Verne,9 and the date of composition was indeed 1898. How can we be sure? In 1892 Verne began to maintain a log in which he recorded the beginning and end dates of composition of each volume (a volume corresponding to a book “part”—The Kip Brothers is, thus, a 2-volume novel). In this log Verne reported the following: “Frères Norik (15 juillet 98—16 9bre), 2e vol. (16 9bre 98—fini 30 Xbre 98).”10 As a result, we know that he began writing The Kip Brothers (whose first title was The Norik Brothers) on July 15, 1898, finishing the first volume on November 16; he then began the second volume the same day and finished it on December 30, 1898.

Nearly three years later, on September 2, 1901, Verne wrote to Hetzel fils (Louis-Jules Hetzel), “I am sending you today by train, registered, a manuscript [first part of the Kip Brothers]. Please confirm by telegram your receipt of it so as to put my mind at ease.” And on October 26, 1901, he wrote, “The second part of the Kip Brothers will leave tomorrow, Monday. You will receive it on Tuesday, and I ask you to please let me know of its safe arrival by telegram.”11 It does appear—and other letters of the same time period confirm this assumption—that Verne selected this novel to be published the following year from among several manuscripts he had already completed. From the mid-1880s onward, Verne was ahead of schedule with his writing and produced more than the minimum of two volumes12 per year required by his contract with Hetzel.13 In 1900 and 1901 Verne had a sizable stock of manuscripts from which he could draw to supply Hetzel with his two volumes for 1902.14

Hetzel received the first volume of The Kip Brothers in September 1901.15 Most of the month of September was devoted to typesetting the novel. Verne received the proofs on September 28, and on October 7 Verne wrote to Hetzel, saying: “I am returning the text of the Kip Brothers to you little by little as I correct it.”16 These corrections and copyediting revisions were done directly on the printed proofs. Between the manuscript and the final printed versions, long sentences were divided into shorter sentences, the rhythm of the action became more active, and the descriptions gained in clarity. The modifications included word rearrangements in sentences and changes of wording that did not change the meaning of the text but made it more readable and improved the style.

After receiving the corrected proofs during the last months of 1901, Hetzel began to print the novel. As mentioned, the “pre-original” edition of The Kip Brothers was first published in serial format in the Magasin d’Education et de Récréation from January to December 1902, and it was illustrated with drawings by George Roux.17

The second printing was in book form and is called the “original” edition, two small in-octodecimo volumes, with few illustrations. The first volume was ready July 21, 1902, and the second was put on the market November 10, 1902.

The third printing was the famous octavo volume with full illustrations, often referred to as “the Hetzel edition” or (wrongly) as “the Original Edition.” This edition was available on November 20, 1902, in three versions: paperbound, “demi-chagrin” (half leather), and deluxe fabric with red-and-gold covers.

Sales of The Kip Brothers, it seems, were generally disappointing. Like other novels published late in Verne’s career, it had difficulty selling out its initial print run of 4,000.18

ILLUSTRATIONS AND PHOTOS

During the latter decades of the nineteenth century, as photography became increasingly popular, many publishers (including Hetzel) began to use photographs, photolithography, and two-toned lithography to illustrate their books. These new technologies gradually replaced the older woodcut-engraving methods because they were cheaper, faster, and less labor intensive.

To see a kind of historical “snapshot” of this technological (r)evolution in the publishing industry, one need only to examine some of Verne’s later Voyages extraordinaires from 1890 to 1905 to see a fascinating mixture of old-fashioned woodcuts, halftone illustrations (some in color), and photographs.

The illustrated edition of Verne’s The Kip Brothers constitutes an excellent example of this trend. One discovers therein four different types of illustrations:

1. Forty drawings by George Roux, engraved by Froment.19 Twelve of the drawings, which appeared as black-and-white illustrations in the Magasin, were reproduced in color in the in-octavo edition (described on the title page as “grandes chromotypographies,” full-page chromotypographs—a kind of early color print). The frontispiece and the title page illustration are also new in the in-octavo edition.

2. A dozen illustrations “borrowed” from other books. Seven, for example, were recycled from the nonfiction works of Jules Verne himself—his three-volume Histoire des grands voyages et des grands voyageurs (History of Great Voyages and Great Navigators)—and one was taken from a book called Voyage of the Griffin (identified as “adapted by P.-J. Stahl” [a pseudonym of Hetzel] and, one assumes, published by him). But three other illustrations in The Kip Brothers were borrowed (should we say copied or stolen?) from a British four-volume work of geography,20 and one—a mosaic of three woodcuts depicting Dunedin, New Zealand, along with a local volcano crater and a geyser—is not credited (although it too probably came from the same British work).

3. Six reprinted photographs.21 The source for two of these photographs was a German book published in 1902, the same year that The Kip Brothers itself was published. It is somewhat ironic that though the text of The Kip Brothers dated from years before, such was certainly not the case for some of the photographs that Hetzel chose to illustrate the book—they were often last-minute selections.

4. Two maps22 of the areas visited in the novel—New Zealand and the Bismarck Archipelago—engraved by a certain “E. Morieu.” The first one was recycled from Verne’s Great Navigators of the Eighteenth Century (volume 2 of his History of Great Voyages and Great Navigators).

SOURCES AND INFLUENCES

As a general rule, all of Verne’s novels are derived from two types of sources: one for the science (broadly defined to include not only physics, chemistry, and biology but also geography) and one for the fiction.

Verne’s sources included those many nineteenth-century dictionaries and atlases of which he made constant use, such as Privat-Deschanel and Focillon’s Dictionnaire général des sciences théoriques et appliquées23 and Reclus’s Nouvelle géographie universelle.24 He also consulted and quoted from a variety of reference books written in layman’s language with the goal of teaching the natural sciences to the general reader—such as Figuier’s Les Merveilles de la science25 or Flammarion’s L’Astronomie populaire.26 Verne was also very well read in the published travelogues and histories of exploration of his time, such as Arago’s Voyage autour du monde,27 Agassiz’s Voyage au Brésil,28 Chaffanjon’s L’Orénoque et le Caura,29 and Charton’s Voyageurs anciens et modernes,30 along with similar accounts published in magazines like Le Journal des voyages and Le Tour du monde. Finally, Verne was also a voracious reader of scientific journals and the bulletins of scientific societies such as Malte-Brun’s Nouvelles annales des voyages, de la géographie, de l’histoire et de l’archéologie and the Comptes-rendus des scéances de l’Académie des Sciences, from which he often gleaned ideas for his novels.31

So what were Verne’s principal scientific sources for The Kip Brothers? Clearly, an important one was the author’s own multivolume history of world exploration, Histoire des grands voyages et des grands voyageurs (History of Great Voyages and Great Navigators, 1878–1880), from which, as mentioned above, a number of illustrations were reprinted. And three other works that helped to provide much of the geographical and historical documentation for Verne’s descriptions of the South Seas islands in this novel were Bougainville’s Voyage autour du monde,32 Dumont d’Urville’s Voyage au pôle sud et dans l’Océanie,33 and Duperrey’s Voyage autour du monde.34

As for the discussions of retinas and ophthalmology presented in the surprise ending of the novel, Verne scholar Marcel Moré and family biographer Jean Jules-Verne have both indicated that Verne probably consulted the L’Encyclopédie française d’ophtalmologie by Lagrange and Valude35 for details about such “optograms” (retina-photos). But these claims seem rather dubious since this nine-volume encyclopedia appears to have been first published in 1903, one year after Verne’s The Kip Brothers came into print and five years after the story was written. It seems more likely that Verne read about the various retina experiments done in the 1870s and 1880s by scientists such as Félix Giraud-Teulon (1816–87) in Paris, Franz Boll (1849–79) in Rome, or Willy Kühne (1837–1900) in Heidelberg. Accounts of these experiments were published in journals that Verne perused on a regular basis such as the Comptes-rendus of the Academy of Sciences of Paris, the Musée des familles, or the Revue des Deux Mondes.

There exist at least two other possible (nonscientific) sources for this idea of optograms used by Verne. One, also mentioned by both Moré and Jean Jules-Verne, is a short story called “Claire Lenoir,” first published in 1867 by Villiers de l’Isle-Adam (and later reprinted in 1887), a copy of which was found in Verne’s personal library. Interestingly, in Villiers’s narrative, the fictional protagonist supposedly reads an article describing optograms published in the minutes of the Académie des Sciences de Paris.36 The other possible source is Jules Claretie’s novel L’Accusateur, published in 1897. This detective novel features a sleuth named Bernardet who, having read Boll’s and Kühne’s articles, photographs the eyes of a victim whose murder he is investigating. He finds inscribed on the dead man’s retinas the image of one of the victim’s friends and promptly has him arrested. It is eventually discovered, however, that the incriminating image is a small portrait that the murdered man was staring at when he was killed. It is interesting to note that Jules Claretie, elected to the Académie Française in 1888, was also responsible for one of the first books of literary criticism on Verne (Jules Verne, Paris: A. Quantin, 1883), so it is quite likely that Verne was familiar with his work.37

From beginning to end, The Kip Brothers stands as one of Verne’s more explicitly visual novels. References to perception and sight abound in the text: from the opening Zolaesque scene in the Three Magpies tavern where the villainous characters Vin Mod and Flig Balt are on the lookout for new recruits; to the trial where the fate of the Kip brothers hangs on the testimony of various eyewitnesses; to the efforts of Mr. Hawkins who “sees” the goodness in the heroes despite the visible evidence against them; to the “eye-opening” conclusion where only an enlarged photo of the victim’s retinas ultimately proves they were framed.38 Again and again, the twists and turns of the plot hinge on what can be seen, on what is hidden from view, and on what looks to be but is not. Given this thematic focus, it is significant that, during this time of his life, Verne was suffering from vision problems—severe cataracts, especially in his right eye. He described his condition in a 1901 letter to his old friend Nadar, saying, “I’m almost blind, and will remain so until my cataract operation. I no longer recognize anyone in the street, barely see what I write, and live in a fog.”39 Verne also frequently refers to his condition in his correspondence with his publisher Hetzel fils. In 1902, for example, during their discussions about adding a subtitle to each of the two volumes of The Kip Brothers (the second volume would be subtitled, interestingly, “The Eyes of the Dead”), Verne writes, “I still have not undergone that cataract operation, and I won’t decide on it until I can no longer read. … But up until now, my left eye has been sufficient.”40 Whether because of doctor’s orders or because, as Verne himself claimed, he did not wish to risk surgery so long as he could see enough to continue reading and writing, the cataract operation would never take place.

The main source for the plot of Verne’s The Kip Brothers is the true story of the Rorique (sometimes spelled Rorick) brothers whose trial became a highly publicized news story in France in the mid-1890s. On June 20, 1894, Verne wrote a letter to his brother Paul in which he confides: “A story that has always touched me is the one about the Rorique brothers, [whose death penalty is] now commuted. There is perhaps something to think about there.”41 Thus, the idea of fictionalizing what came to be known as the “Rorique Affair” was clearly on Verne’s mind as early as 1894. During the final decade of his life, Verne had an Italian correspondent named Mario Turiello and, in three letters to him (written on January 15, May 25, and November 24, 1902), the French novelist links the Rorique Affair directly to The Kip Brothers, saying: “My new novel, The Kip Brothers, which was inspired by the story of the Rorique brothers, has two volumes”; “It’s the story of the Rorique brothers that inspired The Kip Brothers, of which the first volume will soon be available”; and “You say that you didn’t grasp what I meant about the story of the Rorique brothers. Obviously, you don’t read a lot of newspapers. About ten years ago, these fine gentlemen were judged in France and sent to prison for having murdered their captain.”42

Here is the story of the Rorique/Degrave brothers, as summarized by Marcel Moré in his Le Très curieux Jules Verne (120–23):

In July 1892 in Ponape, Micronesia, two brothers from Ostend, Belgium, Léonce and Eugène Degrave (sometimes spelled Degraeve), but better known under their assumed name of Rorique, were accused of having fomented a mutiny on board a French schooner named Niuorahiti, belonging to a Tahitian prince. After having allegedly killed the captain, at least one passenger who represented the cargo company (a certain Mr. Gibson) and several of the crew, the brothers then took command of the ship, modified her, and used her for piracy in the South Seas. Their principal accuser was the (mulatto) cook aboard the vessel named Hippolyte Mirey, a very suspicious character himself and one who was probably involved in the mutiny. After their arrest, the Rorique/Degrave brothers were transferred to France where they were put on trial for murder and piracy.

During the proceedings, it was discovered that, earlier in their career, they had once been recognized and celebrated as true heroes: during a storm at sea, they had single-handedly saved the captain and crew of a Norwegian three-master called the Pieter. But there were also reports of their having lied about having been castaways while in the Cook Islands in 1891. To the charges against them, the Rorique/Degrave brothers repeatedly proclaimed their innocence, saying that the murders had indeed been the result of a mutiny among the crew but one that they had helped to put down. As for the charges of subsequent piracy, they refused to confess to any wrongdoing. Many French citizens who followed the case, including Verne, believed them innocent. Their conduct during the trial was deemed praiseworthy; the brothers remained stoic to the end and asked only to stay together, whatever their fate.

Despite the fact that the prosecution’s case was based on highly questionable witnesses, on December 8, 1893, the Rorique/Degrave brothers were judged guilty on all counts. The tribunal condemned them to death—a sentence that was commuted a few months later by French president Carnot and changed to life imprisonment at hard labor. Léonce died in prison on March 30, 1898. Eugène, who was pardoned the following year, went back to France and wrote his memoirs, which were published in 1901 as Le Bagne (At Hard Labor).43

Perplexingly, a few years later, Eugène abandoned his wife and child and again took up a life of travel and adventure. In 1907 he was seen in Trinidad working as a local policeman. He died in 1929, murdered in a jail cell in Pamplona apparently after having become involved with smuggling a large number of Colombian emeralds out of South America. And, in a final bizarre twist to this tale, the French writer Alfred Jarry demonstrated that portions of his book, Le Bagne, were actually plagiarized from the Adventures of Arthur Gordon Pym by Edgar Allan Poe.44 Here ends Moré’s account of this tale.

Were the Rorique/Degrave brothers, in truth, the innocent victims of conspiracy and judicial error that Verne and others believed them to be? Probably not. But it is clear, not only from his correspondence but also from the strong similarities in plot, names, and characterization, that Verne patterned The Kip Brothers directly on their story, both idealizing and immortalizing them.45 Of course, at the time of the novel’s initial composition in 1898, Verne could not have known that Eugène would eventually be pardoned, return to France, write and publish Le Bagne, and then have his life end tragically amid very suspicious circumstances. But—and this point is crucial—Verne did revise his manuscript during the summer and fall of 1901 before submitting the first part (volume 1) to Hetzel fils on September 2 and the second part (volume 2) to him on October 27. And he was still correcting proofs as late as March 1902.46 During both periods when revisions to the text were being made—along with changing its title from Les Frères Norik to Les Frères Kip—Verne no doubt updated his story in the light of contemporary developments in the case and perhaps even consulted Degrave’s book, Le Bagne.

These 1901 updates and corrections made by Verne to his 1898 manuscript are also very important when considering another possible but less acknowledged source for The Kip Brothers: the Dreyfus Affair. As Cornélius Helling observed in 1935, “This book was written when the Dreyfus affair was causing a stir and [it] has the feel of its era.”47 In fact, if one were not familiar with the case of the Rorique/Degrave brothers or if one did not have access to copies of Verne’s correspondence from the 1890s, one would naturally assume that The Kip Brothers had been based—either partly or wholly—on this legendary case of judicial error and unjust punishment.

The problem is that, during the late 1890s, Verne was a staunch and very vocal anti-dreyfusard. In late 1898, as demands for a retrial of Alfred Dreyfus (in prison at Devil’s Island since April 1895) began to heat up because of new evidence discovered by Lieutenant-Colonel Georges Picquart and by Emile Zola’s inflammatory letter “I Accuse,” Verne wrote to Turiello, saying: “As for the D … affair, it’s best not to talk about it. For a long time it has, for me, been judged and judged well, whatever happens in the future.”48 In a letter somewhat later to Hetzel fils, Verne mentioned in passing “I who am anti-Dreyfus in my soul …”49 And, finally, in December 1898, Verne agreed to became a founding member of a conservative, right-wing, anti-Dreyfus organization called the Ligue de la Patrie Française (the French Patriotic League), created in opposition to the Ligue des Droits de l’Homme (the Human Rights League), a left-wing political group that supported Dreyfus’s cause. Throughout this period, Verne’s pro-government position on the Dreyfus Affair was very clear and well publicized, a position no doubt reinforced by his own anti-Semitic tendences.50

In dramatic contrast to his father, Michel Verne was enthusiastically pro-Dreyfus and did not hide his feelings either. Jean Jules-Verne, Verne’s grandson and family biographer, describes how his father and grandfather repeatedly clashed on the subject:

From the outset his son, Michel, a so-called reactionary with royalist tendencies, was violently outraged by the injustice of the Dreyfus case. I remember that what upset him most was the deliberate procedural error whereby documentary evidence was produced in court without being shown beforehand to the defence—particularly since the document concerned turned out to be a forgery. Obviously, Michel’s visits to Amiens at this time could not help being stormy ones. They might have resulted in a momentary breach with his father; but fortunately their affection for each other was by now such that their relationship emerged unscathed. In any case, Verne’s judgment was too sound for him not to see eventually that his son’s indignation was justified; but to admit that much he had to sweep aside a good many beliefs that he had always regarded as inviolable.

This made him all the more disposed to listen to the opinions of his prodigal son, who had turned out to have a cultivated and alert mind with which Verne could communicate.51

Could it be that, between 1898 and 1901 when he was to revise the text of The Kip Brothers, Verne slowly began to “see” his son’s point of view on this matter? Could it be that he began to acknowledge that there were profound similarities between Dreyfus’s unjust imprisonment and that of the Rorique/Degrave brothers on whom his own fictional protagonists were based? Could it be that Verne, unable or unwilling to “sweep aside a good many beliefs that he had always regarded as inviolable,” purposefully embedded in the text of The Kip Brothers certain clues that reflected his change of heart about the Dreyfus Affair as he was preparing the final version of the manuscript in 1901?

Such is the premise of Christian Porcq in a seminal two-part article on Verne’s The Kip Brothers published in the Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne in the winter of 1993–94.52 In a provocative analysis that ranges from the factual to the far-fetched, Porcq argues that Verne—a lover of riddles, puzzles, and cryptograms—hid in his text a host of references to the Dreyfus Affair. Some are lexical: repetitions of certain words such as “affair” and “proofs” (legal as well as photographic—where Dreyfus is a kind of “negative” for the Kip brothers) or phonological anagrams in the fictional characters’ names (like KAR[L]KIP which could conceivably be an inverted PIKAR, that is, Picquart, the name of the French officer who investigated Dreyfus’s case). Some are chronological: the fact that Karl Kip is thirty-five years old when he was arrested (the same age as Alfred Dreyfus at the time of his arrest) or that the three successive court trials portrayed in The Kip Brothers (that of Flig Balt in January 1886, that of the Kip brothers in February 1886, and the Kip brothers’ retrial in August 1887) parallel the timing of the court trials in the Dreyfus Affair a dozen years later (that of Esterhazy in January 1898, that of Zola in February 1898, and Dreyfus’s retrial in August 1899). And some clues can even be found in one of the novel’s illustrations: the portrait of Mr. Hawkins in chapter four bears an uncanny likeness to Edgar Demange, Dreyfus’s defense attorney. According to Porcq, despite Verne’s overt anti-Dreyfus views during the late 1890s, the author nevertheless secretly patterned much of his story on the legal tribulations of the French officer. Porcq’s reading of this novel is fascinating but, ultimately, not entirely convincing. Verne’s anti-Dreyfus views toward the end of his life seem as strong as before he published The Kip Brothers.

Finally, another source for The Kip Brothers was Verne’s own first-hand experience with the sea and the nautical life. As Jean-Paul Faivre has observed, The Kip Brothers is one of Verne’s most “oceanic” novels.53 And the Pacific Ocean is used as the fictional locale for many of Verne’s Voyages extraordinaires (The Children of Captain Grant, Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas, The Chancellor, A Captain of Fifteen, and The Stories of Jean-Marie Cabidoulin, among others) as well as in some of the author’s very first short stories.54 From the earliest days of his youth exploring the docks of the seaport city of Nantes, Verne had a consuming passion for the sea. His grandson writes: “Undoubtedly, it was in Nantes that Verne’s love for the sea made its first mark on him, a real love that many years later led him to remark: ‘I cannot see a ship leaving port … but my whole being goes with her.’”55 Verne owned three yachts during his lifetime: the first, a nine-ton built-to-order vessel launched in 1868 and baptized the Saint-Michel I, in which he sailed out of the port of Le Crotoy (and aboard which he wrote much of Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas); the second was the Saint-Michel II, bought in 1876, which he owned for less than a year; and the last, purchased in 1877, was the Saint-Michel III, a luxurious steam and sail yacht with a crew of ten, in which Verne sailed to various ports of call throughout the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the North Sea until early 1886. When Verne was writing about ships and the sea, he knew the subject well.56

Verne’s nautical expertise is often reflected in the pages of The Kip Brothers. For example, consider the following passage when Karl Kip takes command of the brig James Cook during a ferocious storm at sea: “The storm, although extraordinarily fierce, was less dangerous, since it now attacked the ship by the bow, and no longer by the stern. The crew managed to set up, not without great difficulty, a heavy-weather jib, capable of resisting the wind’s blasts. Under its storm jib and its small topsail whose reef Karl Kip had unfurled, both of which were trimmed tightly, the brig held close to shore, while seaman Burnes, an excellent helmsman, imperturbably maintained the James Cook on its proper course.” While penning this particular scene, the author was no doubt recalling some of his own early maritime adventures aboard the Saint-Michel. As Verne’s grandson Jean Jules-Verne describes it in his biography, “There can be no doubt that the thoughts of his mariner heroes were his own. … Hence, the importance of the Saint-Michel in his life and works cannot be overstated. Even though he visited few of the faraway places frequented by his heroes, he was a sailor, well versed in sailing and broken to [familiar with] the dangers of the treacherous seas between Boulogne and Bordeaux.”57

NATIONALITIES, REVOLUTIONS, AND BROTHERHOOD

Another interesting aspect of The Kip Brothers—and one that distinguishes it from most other novels in Verne’s Voyages extraordinaires—concerns how certain nationalities are portrayed. The novel’s plot unfolds in Tasmania and New Zealand, former British colonies, and in the Bismarck Archipelago, which belonged to Germany. Most of the main fictional characters are therefore Anglo-Saxons and Germans, with the two heroes of the novel, the Kip brothers, being Dutch. This particular configuration in his cast of characters is a very unusual one for Verne, for two reasons. First, the majority of the protagonists in Verne’s works tend to be British, American, or French.58 The only French and American characters appearing in The Kip Brothers are secondary and clearly minor: the captain and sailors of the French ship Assomption, who announce the wreck of the Wilhelmina to the passengers and crew of the James Cook, and the unsavory American seamen Bryce recruited in the Three Magpies tavern at the beginning of the novel. Second, Verne depicts the British and Germans in this novel in a very sympathetic light. The Kips’ tireless advocate and friend Mr. Hawkins; the governor of Tasmania, Sir Edward Carrigan; and even the warden of the Port Arthur penitentiary, Captain Skirtle, are shown to be fine and honorable British gentlemen.59 And Mr. and Mrs. Zieger of New Mecklenburg as well as Mr. Hamburg of Kerawara exemplify the best of German warmth and hospitality as they welcome the captain of the James Cook and the Kip brothers into their homes during the ship’s layovers in the Bismarck Archipelago.

These approving portrayals contrast sharply with Verne’s more cynical representation of these same nationalities in several of his other later works. Note, for example, the many diatribes against the British in the pages of such novels as The Mysterious Island (their conquest and domination of India), Hector Servadac (their jingoistic “Gibraltar” mentality), Lit’l Fellow (their terrible treatment of orphans), and especially in his 1895 Propeller Island (the greedy English imperialists of “perfidious Albion” are “cursed down to their children and grand-children, until its detestable name is wiped from the memory of the world!” And Verne’s depiction of Germans follows a very similar trajectory. During the decade immediately after the Franco-Prussian war, Verne’s first truly evil scientist emerged in the person of the racist megalomaniac Herr Schultze of The Begum’s Millions. Other anti-Germanisms punctuated many of Verne’s subsequent novels, such as A Drama in Livonia (in which Germans brutally oppress the Slavs) or in Claudius Bombarnac (in which the contentious and crude Baron Weissschnitzerdörfer personifies most Germanophobic stereotypes of the fin de siècle). As Verne scholar Jean Chesneaux has explained, however, it is important to understand that Verne’s

hostility towards England hardly ever stems from simple national chauvinism; it is politically motivated. England is castigated as the oppressor of the Scottish, Irish, and French Canadian nationalists, or for being a great colonial Power. Verne’s Anglophobia is directed towards a country regarded as typical of certain negative political tendencies, much more than towards an ‘enemy’ nation. …

In the same way, Verne’s Germanophobia, with the exception of one or two casual and ridiculous characters, is invariably linked with political criticism. … Even in this case [The Begum’s Millions], symptomatic of the extreme vengeful chauvinism widespread in France in the 1880s, the ‘eternal German’ Schultze is indistinguishable from Schultze the armament industry magnate, the master of a gigantic totalitarian and, so to speak, proto-Hitlerian complex, a scientist who uses his knowledge in the service of destruction.60

Although there exists no iron-clad correlation between an author’s personal politics and those expressed in his fiction, it is nevertheless interesting that Verne’s portrayal of the British and the Germans in The Kip Brothers recalls those of a much younger Verne—a Verne of the 1860s whose earliest works featured the courageous and resourceful British explorer Samuel Fergusson in Five Weeks in a Balloon and the delightfully eccentric German geologist Otto Lidenbrock in Journey to the Center of the Earth.61

But perhaps in The Kip Brothers it is less a question of nationalities and more of nationalism. Consider, for example, Verne’s favorable portrait, late in the novel, of the Fenians, who have “the goal of freeing Ireland from the intolerable domination of Great Britain.” They also play a part in his novel about Ireland published in 1893, Lit’l Fellow, in which Verne describes the British aristocracy in the following terms: “It is nevertheless important to note that the aristocracy, which is rather liberal in England and Scotland, has shown itself to be quite oppressive in Ireland. Instead of offering a helping hand, it jerks on the reins. A catastrophe is to be feared. He who sows hatred will eventually harvest rebellion.”62 Throughout the Voyages extraordinaires, Verne repeatedly expresses his sympathy for oppressed peoples and his support for nationalist movements. Captain Nemo of Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas (1870) aids the revolutionaries of Crete in their fight against the Ottoman Empire by donating to them riches taken from the sunken galleons of Vigo Bay. The French Alsatians’ hatred of their post-1870 German occupiers is a leitmotif running through The Begum’s Millions (1879). The heroic Greeks are shown battling for their independence from the Turks in Archipelago on Fire (1884). The efforts of Hungarian patriots to regain their country’s freedom from the Austro-Hungarian Empire serves as the political backdrop for Mathias Sandorf (1885). Norwegian separatists occupy center stage in The Lottery Ticket (1886), set during a time when Norway is under Swedish rule. In Family without a Name (1889), the French Canadians struggle to free themselves from their British masters; in the preface to this novel, Verne even suggests that they are setting “an example that the French populations of Alsace and Lorraine must never forget.”63 And in A Drama in Livonia (1904), one of the last novels published before his death and another a novel of “judicial error” similar to The Kip Brothers, Verne focuses on the Slavic peasants and their struggle against the wealthy ruling classes, who are of German extraction. In novel after novel, Verne shows himself to be faithful to the republican ideals of the Revolution of 1848, which he experienced first-hand as a young man in Paris and whose precepts he adopted as his own. A strong believer in social justice, Verne continually embeds in his fiction a sense of brotherhood with the downtrodden peoples of the world who are fighting for their freedom.

But The Kip Brothers stands as one of Verne’s greatest tributes to brotherhood not only because of how the author portrays the rapport between the novel’s two heroes or his solidarity with certain nationalist political movements such as the Fenians. A strong sense of brotherhood also resonates throughout this novel on a more personal level—Verne’s fraternal love for his brother Paul who died in 1897, the year before he began to write The Kip Brothers.

Paul Verne was a year younger than Jules, and the two had always been very close. In an interview with a journalist in 1894, Jules Verne described their relationship, saying,

My brother Paul was and is my dearest friend. Yes, I may say that he is not only my brother but my most intimate friend. And our friendship dates from the first day that I can remember. What excursions we used to take together in leaky boats on the Loire! At the age of fifteen there was not a nook or a corner on the Loire right down to the sea that we had not explored. What dreadful boats they were, and what risks we no doubt ran! Sometimes I was captain, sometimes it was Paul. But Paul was the better of the two. You know that afterwards he entered the Navy.64

Paul enlisted as a midshipman in the French Navy in 1850 and joined the merchant marine in 1854. He soon retired from the sea and became a stockbroker, but he and his brother continued their seafaring excursions. In 1867 they crossed the Atlantic together on the Great Eastern (a voyage that became the basis for Verne’s 1871 novel A Floating City) and visited New York and Niagara Falls. And they often voyaged together aboard Verne’s yacht the Saint Michel III—in 1881 traveling to Copenhagen, for example, a trip that inspired Paul to publish an account of their adventure, “From Rotterdam to Copenhagen,” in the Nantes newspaper L’Union Bretonne that same year. Earlier, in 1872, Paul had published a similar travel chronicle in the same paper called “The Fortieth Ascension of Mont Blanc,” which was later reprinted in Verne’s first short-story collection, Doctor Ox (1874).

On many occasions, Paul Verne helped his brother with the technical aspects of the stories he was writing. For instance, when working on the manuscript of Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea in 1868, Jules wrote to his father, saying, “In three or four months, when I have the proofs, I will try to send you and Paul the first volume so that you can clean up some of its errors or imperfections. I really want this machine to be as perfect as possible.”65 And when working up the preliminary engineering designs for his “Standard Island” in Propeller Island (1895), Verne repeatedly consulted with Paul, asking for his technical advice. The following excerpts from their correspondence of this period are typical:

Amiens, 5 June 1893

My dear Paul, … Next year I will really need your help for my propeller island, so as not to make any stupid mistakes. The first volume is written. The second will be in 3 months. I’m much ahead of schedule. The island is large, 25 to 30 kilometers around. Do you think that it can be steered without a rudder by using two propeller systems on each side powered by dynamos run by machines generating a million horsepower of force? … Tell me when you can, as you’re waiting for me to send you the proofs.66

Amiens, 8 September 1893

My dear Paul, I received your letter, which has crossed my own in the mail, and I will send you today the proofs of the end of volume 2, which you can return to me when you’ve looked them over. I have rewritten according to your corrections, which I am using verbatim.67

Amiens, 12 September 1894

My dear Paul, … I suspect that I have made many errors, and that’s why I sent you the proofs. But it is not enough to point the errors out to me; you must indicate to me how to fix them.68

Amiens, [October?] 1894

My dear Paul, I have just received your letter and the proofs. I thank you for the huge amount of work you have done. Without you, I would have never been able to manage this.69

It has often been argued that the pervasive and sometimes pivotal influence of Verne’s editor-publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel in shaping the content of the author’s Voyages extraordinaires has been underestimated. It seems that Paul Verne’s contributions to the fundamental design of some of his brother’s legendary “dream machines” is also a story that remains to be told.

But it was especially Paul who served as his brother’s most trusted confidant during those often-traumatic years of the late 1880s and the 1890s when Jules was repeatedly beset with a host of physical, emotional, and financial problems. As the biographer Herbert Lottman has observed, “Family correspondence, which sheds so much light on the life of the young Jules Verne, is missing for the middle years when Verne gained literary renown. But there is another rich lode of letters, beginning in 1893 to draw upon. These letters were written to one of the few people in whom Jules never ceased to confide—his brother Paul, who was now turning sixty-four.”70 Foremost among Verne’s concerns were the continuing difficulties with his son, Michel, whose repeated career changes and bankruptcies, costly amorous escapades, divorce from his first wife, and difficulties with the law caused Verne at one point to complain to Paul “the future frightens me considerably. Michel does nothing, finds nothing to do, has cost me 200,000 francs, has three sons, and their entire upbringing is going to fall on my shoulders. I’m ending badly.”71 Verne’s growing financial worries had earlier forced him to sell his beloved yacht, the Saint-Michel III, and he would never again sail the open seas, with Paul or anyone else. Then, on March 9, 1886, he was attacked at gunpoint by his deranged nephew Gaston and shot in the lower leg; he would remain partially crippled for the rest of his life. Later that same month, his publisher and “spiritual father,” Pierre-Jules Hetzel, died. Soon thereafter, in speaking with Hetzel’s son, Verne confessed, “I have entered the dark period of my life.”72 The following year, his mother died. And during the ensuing years, in addition to having to walk with a cane, Verne was plagued by a variety of physical ailments, including severe gastrointestinal problems, recurrent dizziness, rheumatism, cataracts, and diabetes. In a letter to Paul in 1894, following the June marriage of his niece Marie, the author confides, “I see that the wedding was very jolly, but it is precisely this sort of merriment that is intolerable to me now. My character is deeply altered, and I have received blows from which I shall never recover.”73 When Paul Verne died of heart disease three years later, on August 27, 1897, Jules was grief-stricken, saying, “What a friend I have lost in him!” and “I never thought that I’d outlive him.”74 According to his grandson, Verne “was so crushed and so ill that he could not attend the funeral.”75 With memories of his deceased brother fresh in his mind, Jules Verne began work on The Kip Brothers the following summer.

Some of Verne’s novels have been called “visionary” for their unusual scientific or technological prescience. The Kip Brothers might also be termed “visionary,” but in an entirely different way. The strongly visual nature of its thematic content—from the initial sighting of the castaways to its strange ophthalmologic conclusion—underscores Verne’s own worsening eye problems during the late 1890s. As reflected in the novel’s plot, two real-life dramas of judicial error can also be easily visualized (one acknowledged by Verne and one not): the Rorique/Degrave brothers’ trials and the infamous Dreyfus Affair. Finally, The Kip Brothers envisions—or, more correctly, re-visions—its author’s personal past as Verne builds an idealized literary memorial to his relationship with his beloved late brother, Paul. It is ironic that one of Verne’s most sight-oriented Voyages extraordinaires has become, since its publication, one of his least visible works. It is our hope that this first English translation of Verne’s Les Frères Kip will help to remedy that situation and to show the Anglophone reading public a new and different Jules Verne from the one they had thought they knew so well.

Jean-Michel Margot