Читать книгу Look Both Ways - Katharine Coles - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

A SELF DIVIDED

To speak is also to be.

ISABELLE ALLENDE

WALTER LINK is absolutely a man!

It’s a passing reference in my grandmother’s diary, but I make a note. In fall of 1923, Miriam Magdalen Wollaeger was a sixteen-year-old freshman at the University of Wisconsin. She’d met the man in question, who would become my grandfather, at the Lutheran church supper. About Tom, my grandfather’s first rival, she wrote, There is someone who feels like I do, to whom I can tell my strange ideas and have them appreciated. And, He wants to read my poems, a line we’ve all heard. In spring of ’24, about Al: He has a dandy blue canoe, with all the equipment one could think of, including cooking utensils. Not to mention a little flivver, small like her, and dashing, blue to match her eyes. He loved that she drove like a man, much too fast.

Sensibility. Gear. Manhood. Her words are my window and my mirror. Packing for my flight to Wisconsin, my first trip in their footsteps (archives, I say to my husband, Chris, who likes to know where I am going and why), I imagine the girl who will become my grandmother looking for a combustion engine and a full tank, for someone to pick her up and move her, for transport.

Walter, five years older, I see less clearly. After the church supper, he lingered on Barnard Hall’s front porch until it was time for her to sign in. Already careful of her, he watched the clock. The next day, he took her for a walk in the snow, a date he could afford.

Frugality. Discipline. Family virtues, I’ve been led to believe, that made him a successful explorer and made her think she should love him. The linear head of a scientist; the lean physique of a cross-country runner. Tall and brooding, he had the long nose that came through my mother to me and impossibly big feet that would torment him on journeys seeking oil in the tropics. If Miriam by virtue of sex and class could flit from English to music to French to zoology, Walter stayed focused, determined to thrive. I think he is very sensitive, and considers himself inferior in some ways—dear little (?) dumbbell! Miriam could afford to view education as class ornament, but, like me, Walter’s father earned his meager living, until he lost the power of speech and could no longer deliver his sermons, from the word.

Among his children: an attorney, a botanist. Karl Paul, chemist and inventor of warfarin, twice won the Lasker Award and was rumored to have been short-listed for the Nobel. Two petroleum geologists. Margie and Helene had orchids named for them; Ruth was a milliner. Ten children survived. Like most of them, like me, Walter became an atheist, hard headed and willing to rely on himself in everything but love. He was, I think looking back, as American as oil, absolutely of his time.

Then Al began to woo her, and, though Walter promised to take her canoeing (I hope he does!) as soon as the lake ice melted, he had no boat to match that blue canoe, much less a fast piece of sky on wheels.

And Miriam: what was she? Eighty years later, I find among her papers a poem penciled in a bluebook, returned ungraded because she was supposed to turn in an essay. In just this way, I troubled my college French professor by translating Baudelaire in place of grammar exercises. I imagine her lying on her dorm-room bed, wondering what it would be like to bushwhack through jungles and gaze from mountaintops over wild landscapes.

To plough the foaming waters of the boundless Spanish main,

To plunge amid the swelter of a pelting tropic rain,

To wade thigh-deep against the racing waters of a stream—

All these would be fulfillment of my highest, golden dream.

It’s formally predictable, but not bad, I think, for sixteen. Embodying desire, she spins through a Wisconsin blizzard on lamplight and white sheets, piloting her own boat. I follow her onto the water, our keel slicing the waves, moving us forward through active and vivid images:

To hear the billows swishing as they’re riven by the bow,

With their crests like smoke a-flying, lighting dark green depths below,

To feel the rush and smother of a million airy bubbles—

Here, at the end of the second stanza, comes the moment when the poem moves from its sustained provisional infinitive—to plow, to plunge, to feel—and into the present, where the journey becomes embodied, or so I expect, in her—

O, the dash and vigorous joy of life make a fellow lose his troubles!

Did this line trouble her as it does me? Sixteen-year-old Miriam, pining for adventure as I did, enters her dream—in a boy’s skin. I remember this: when I was growing up, too, all the heroes were boys, except the intrepid Nancy Drew, who had Ned. Miriam had to take some trouble to accomplish her split, shifting from me in the last line of the opening stanza to the third-person fellow in the last line of the second. Did it occur to her that this shift stops the poem short, disturbing both its rhythm and its logic? Did she even consider “the dash and vigorous joy of life make me lose my troubles”? If she were my student now, I would tell her, look there, into the poem’s flaw, for its key. If she were myself, oh, I could have taken her in hand.

Walter Link is absolutely a man!

Asail on that bed, plowing through the night, she can’t hear me. What more could any man desire? Her spirit calls, but she can’t follow. In the final stanza, when her speaker separates from that fellow and they go their separate ways, she has to stay home.

A square of window, whited out. I want to break away as did ‘Desmond’, dress as a man and fight my way. Movies and novels and her own poem notwithstanding, her will was weaker than her desire. She wouldn’t step into those britches she’d stitched from words and go. I have always envied her life’s romance and, yes, adventure. Now, I watch her begin it daunted, already divided. She imagined motion, imagined the vast unknown, imagined moving through a world that never existed. She called her poem “Adventuring.” What she couldn’t imagine: herself.

Absolutely a man. An American of his time. She couldn’t become him.

Instead, with her mother’s help, she would marry him.

But why could she not become him? To my mother Joan, even Miriam’s accomplishments represented her failure to live up to her gifts. She read Latin and spoke fluent German, French, Dutch, Spanish, and Malay as well as English; she was a student of violin and voice whose music teacher urged her to drop everything but her fiddle; she was a championship swimmer, diver, horseback rider, polo player; at barely twenty she received a degree in geology from the University of Wisconsin; she had the largest working vocabulary of anyone my mother, who herself earned PhDs in geology and psychology, has ever known; she traveled around the world twice before the advent of passenger flight; she lived in Colombia, Java, Sumatra, Costa Rica, and Cuba.

I have always been amazed that she managed all this as a woman in her time, even if her travels were made not on her own sweaty nickel but on that of her husband, my grandfather. Behind my eyes, Miriam touches the hem of my wedding dress, its lace hand-pearled for her own marriage sixty-two years before mine; in her filthy Sarasota kitchen, still missing Havana, she makes me paella from the contents of a box, three cans, and Florida tap water; at eighty-five, she sets down her beer and tilts her head, wattles trembling, to pour a raw oyster into her red-lipsticked mouth; she skids her Pontiac into the supermarket parking lot, tires screeching. Even in her Florida old age, where she looks like any other pensioner, I admire and envy the romance of Miriam’s life, all the things she told me that she never told my mother, her entitlement. I even admire her driving, her heavy foot, her muttered curses and refusal to give up her keys. She made her own way in a world still deeply unfriendly to women. She loved her children and resented being a mother. Like her mother and mine, like anyone, she succeeded and she failed.

By twenty-two, Miriam had traveled every hemisphere, a goal I wouldn’t accomplish until I was in my forties. There are worse reasons to marry. In her place, her time, could I have been braver? With all my freedoms, can I now?

Still, I have to consider the possibility that she should have done everything differently. Wherever she lived, she left her children with servants to play bridge, polo, tennis; she went out dancing; she flirted, and more, with aviators and deputy consuls. Oh, my mother remembers, Miriam was glamorous, bolero-jacketed, sequined. Chanel No. 5 lingered in every room she left.

She should have become an explorer like Walter, persuading the oil companies (her mother, her husband, herself) that she, too, could cut her way through the jungle with a machete while her precious brats stayed—where?

She should never have had children. She should have stayed home. She should never have married. She should have married somebody else.

She should have given more to her children or taken more for herself. She should not have been angry at what she’d given up. She should have given up nothing.

She should have been the exception. She should have done it all and done it alone.

She should have been everything she was and more, should have been ordinary. She should have been something else altogether.

I begin to imagine what flights I might undertake myself. Her flaws notwithstanding, to me she glitters. She is not only romance, but history.

She wasn’t even sufficiently herself. I don’t know what I want or think or feel. Miriam’s own mother, Mandy Gettelman Wollaeger, daughter of a brewer and married to a furniture business until it failed, was famous in Milwaukee for charm and hospitality, especially toward men, and in her family also for cruelty, which she taught to her daughter in exquisite lessons. Four foot ten, dictatorial, willful, she managed her children with deft rigor. With her husband, Louis, she had less success.

Even as a small girl, Miriam cooked for her spoiled older brother, Louis Jr., and younger sister, Tony, saw them off, then delivered breakfast to her mother in bed before hurrying to school herself. Female and thus fatally flawed, she became her mother’s petted companion and reviled servant. My Darling Petty, Mandy addressed letters all her life, and Mother’s Dearest Blessing. Mommy Darlingest, Miriam wrote, until she was nearly forty. Baby, she called my mother, over Joan’s furious protests, until she died.

Mandy, having watched her dull brother get the education she longed for, made sure both daughters went to the University of Wisconsin, just as my mother left no doubt that I would go to college and probably graduate school. I am merely fulfilling her own dreams. Still, in 1923 as in the 1890s—as, indeed, in the 1950s, even the 1970s—there were few clear paths for a woman seeking a life beyond that of wife and mother. Like Mandy before her and my mother after, Miriam chafed against her restraints but couldn’t overturn them or sidestep them. Instead, she created loopholes. To imagine herself in action, Miriam thought herself divided. Through beating men at sports, through conversation, through charm, she became the exception: honorary member of the male sex, object of men’s desire, so lively they mistook her for beautiful.

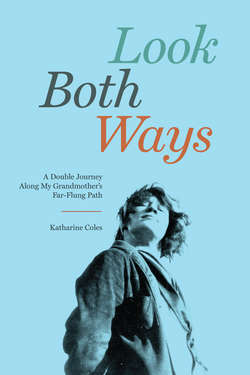

Miriam, Lakeside, Wisconsin, 1925

I count Miriam’s admirers at school: Edgar, Skeex, Ets, Leo, George, Tom Lake, both Link brothers. When I suggest Miriam got around, my mother defends her. Things were different then: a whirl was what a girl lived in; being seen too much with one boy was what she had to avoid. Fellows do make better friends when they are real friends than girls.

In November 1924, Walter took Miriam to watch the northern lights play over Lake Mendota. She saw four movies a week, emotion flickering in the darkness, but nothing could equal the aurora for taking her out of herself. They sang “Stille Nacht,” Miriam’s mezzo soaring above Walter’s bass and over the water.

As you say the German songs are always a font of understanding. Miriam sent Mandy his photograph—He looks like a very nice fellow—then took him home for Thanksgiving.

What passed between Walter and Miriam that weekend? Between Walter and Mandy? I think he is the kind you can respect and admire. As he walked in the front door, Mandy took his arm—her head barely cleared his elbow—and led him off to her sitting room to apply her wit. The kind of work he does will keep him wholesome and clean inside and out. She adopted his nickname, Brutus. Friendships such as his will have a good influence over you. And she adopted his pet name for Miriam, his Muckie.

It was Miriam who couldn’t decide. He’s a dandy kid, she wrote to her mother. But her dreams were shaped by the stories she already knew. To her journal: I will be a solitary girl—until someday the man of my dreams wakes me, and then I can do anything. Oh, I will love him (if only I don’t make any mistakes first. God please guide me!).

The world tells her to give over, to keep herself in check, to slumber. Through time, I see myself in her—small, straight-bodied, self-absorbed, often frustrated, uncertain, reckless, secretive, her head easily turned by novelty, by beautiful clothes, by men. I want her to be wise. I’m destined to be forever in doubt as to which man of several I like best. It is a sad weakness. Over ninety years have passed. I would not want to have missed it. She has had some glimmerings, but she is not wise yet, and neither am I.

I remember ice skating on Lake Mendota during the year we spent in Madison; trying not to draw my grandmother’s eye, or her temper, by getting underfoot in Milwaukee; picking wild, intensely sweet blueberries with my brothers on the windswept shores of Lake Superior, running as wild as they did, getting lost. I don’t remember Mandy, who held me only once not long before she died, already descended far enough into her dementia not to know me any more than I could know her. Now, looking into a more distant past, I rummage in the Wisconsin Historical Society archives for newspapers advertising dresses Miriam might have bought and movies she might have seen; I walk downtown, identifying buildings that would have been here when she was young, trying to picture still-unpaved roads gone muddy after rain.

On campus, I buy an ice cream at the old Babcock Hall Dairy Store, which my parents would have patronized in the fifties. I tour Barnard Hall with its visible ductwork, tall windows, and original radiators, still crisply new when Miriam wrote her poems and letters there, now advertised as historic.

January 1925: a new diary. D’you suppose I’m falling in love with Brutus? There was a line, invisible and moving, she was always about to cross, had just crossed. Miriam, at seventeen often late like my mother, like me running to catch up with herself, strewing ribbons and buttons and torn stockings in her path, tried when he arrived to come down promptly (notice!) hair up and everything.

They went to see North of 36 at the Strand. His touch thrills me. After the film, they met his elegant brother Karl Paul at the Chocolate Shoppe. K.P. and I had a battle of wits. But Brutus squelched him, saying, “She goes with the man, not the clothes.” Little did he know. She loved play, dance, immanence and its delicate timing.

Absolutely a man. She didn’t stop to wonder what that meant.

The scene as I play it begins with the pair not touching. I wonder if he really loves me? He steps into her; she backs away, foot mirroring foot, shoulder-to-shoulder, pushed before him as if by a magnet’s negative force. Leading, he steps back. He has no money. Breast, hip, thigh: he draws her forward, the space between them neither opening nor closing. At last, the distance narrows. When he pulls her into his arms and whirls her into the night, I sigh.

But Walter would never really learn to dance. She had to learn to make it look like she was following. I wanted so to have him kiss me goodnight, but unless I act rather lingering, he seems to lack the courage.

If I could speak to them, what would I say? He didn’t take her into his arms. At The Thief of Bagdad, Miriam thought not of Walter beside her but about a distant land, a man returning to claim his beloved on a magic carpet. The old discontent and restlessness and wanderlust stronger than ever. She was miles away. She felt distracted, introspective. If only I had enough character to know what I wanted!

I find a Chocolate Shoppe in Madison, founded in the sixties, long after their time. There is no dance floor. Though the Orpheum Theater, built in 1926, still stands on State Street, its iconic sign competing with the capitol dome for attention, the Strand was demolished in 1990 to make way for a parking lot, its façade hauled off and tucked into storage in some Historical Society warehouse, awaiting a future that wants to see it again.

My mother’s cousin Tom lives in the house Karl Paul built in the 1930s on a hill outside town. He and I sit on the terrace drinking wine, looking down the long lawn where as a child I chased fireflies through the grass. Though Karl spent the northern winters locked in depression behind his study door, I knew his summer self, my mother’s favorite and also mine among the great aunts and uncles; his gentle-humored wife Elizabeth a progressive and lovely anti-Miriam, unpainted, hair smoothed into a simple bun, who channeled her own brilliance without apparent resentment into her children and courteous but passionate activism. Tom, who has her bones, is bemused, as I was, to learn that his father, whom we both knew as a white-maned and gently ironic man of science, possessed a shadow self, a devil in wit and on the dance floor too.

Miriam, Lakeside, Wisconsin, 1925

In February, during Walter’s second visit, Mandy was exercising her temper on her husband, who, when she wouldn’t give him money, borrowed from friends he never repaid. I’d never marry if I thought there’d be such unpleasantness.

Used to real hardship, Walter fitted himself in, working puzzles, praising Miriam’s cooking, helping Lou work on the Ford. Sitting alone, he listened to Bach and Beethoven on the Victrola, each note a little miracle only money could buy.

When they got back to Madison, the closeness of the visit held, just long enough. I told my beloved that I love him. In love with the dance. For the moment, she was right there, under his hand.

Two weeks earlier, K.P. had confessed his love, the second man that day. If Brutus weren’t so much in love—like her, he was a tease, light and brittle and quick, happy to watch himself woo. His mouth to her ear, the brasses scorching the air—she was his feather, his Ferris wheel gone wrong, his reckless schooner: I, too, have imagined myself free yet utterly mastered. If only Brutus isn’t hurt and martyrish. She laid her head back and laughed. I’m not going to tell Brutus at all. When she put it that way—but what could she do? And why did he refuse to see?

In May, Miriam rode horse drills in the big parade. Major was ten times her weight, the ground wet and slick, the horse’s hooves slipping. She was leading, in control, but all Walter saw was how small she looked, back straight, thighs straining to grip the horse’s body. He was a flicker on the edge of her mind. I am almost afraid that he is cramping my style.

Mandy had forbidden her to go out with Walter more than two nights a week. Had she expected Miriam to resist, to make of this obstacle a stronger bond between herself and her lover? Are you getting tired of the boy? Be careful what and how you say and do things.

What did Miriam long for? Her lover. Her mother. Sometimes she confused them. Every night they didn’t see each other, Walter called to tell her what time to go to bed. He believes he’s been appointed regent in your absence. She wanted privacy of mind and to be understood. She wanted love and freedom. I know how this is, though I came of age in a different time, with different risks, different protections, buying and carrying condoms long before I ever planned to use them, in the years immediately following Roe v. Wade. Perhaps my letters are, as you say, shorter and dumber. How could she say what she felt or wanted to the tiny woman with the stinging slap? She didn’t know herself. She looked at Walter awash in sweet longing. She never wanted to see him again. In her journal, she asked for a big handsome man with a rich car to take me riding in my cute new clothes, and he would take me places! A means to an end. O, I know it’s wicked and ungrateful. Love. Liberty. For either, she would have to give up something she hadn’t tasted. She dreamed she could go back, that she and Mandy could be close as lovers again, and she wouldn’t have to choose. Then my Mommy and I will go bummin’ together and have a gorgeous time afterwards in a nice little house by the sea.

One Saturday evening, she and Walter went to the pump house, which sits at the lake’s edge, the water that feeds its intakes lapping beneath the foundation. Among the hydraulic equipment, the smell of the lake rising from beneath their feet, she felt shy and young and itchy. My goodness, Brutus was bold. Pressing back, backing away. I guess I haven’t been strict enough. After he left her at the dorm, she lay awake, flushed and disturbed. He’s getting a bit too passionate and I mustn’t let him.

It’s summer when I visit, and the building, now housing laboratories, is cool and quiet. With its modernized interior, it floats in layered history. Not far from here my parents would meet at a Hoofers Club party, my father lying on the floor plucking his mandolin until my mother stepped on him. Did she really break it, or is that my invention? She was majoring in geology to prove to her father she was worth as much as any boy. My parents, too, would marry in Milwaukee, stepping off Miriam’s porch into new lives. I would marry in my own hometown, where I now live with Chris, from the Ladies Literary Club. Like Walter, like Chris, my father was in love, I presume, and hopeful. My mother, as always, was dazzling and angry. Was she also, like me, in love?

On Sunday, Miriam waited for Walter to phone, but he left her to herself. It’d be just my luck to fall in love with him when I can’t have him. Only then?

The next day was a Monday, a perfectly gorgeous night, one of the evenings they weren’t to see each other. When he called, she was already half carried away. I simply had to go out for a walk with him, and so we went up on top of the ski-slide. Across the lake there were just one or two lonely lights, while the stars were so big and bright they looked as if they were on fire.

A child. Why should she have seen how ill-suited they were? Not love, the idea—

When I told him he was naughty and asked him if he thought he’d ever get to heaven, he said he was as close as anyone could get right then.

Filigree of leaves against bright sky and water. Night air soft and close, fired with starlight. Soft pine duff underfoot; clothes rubbed thin at knees and thighs. That June, Walter came to the Wollaegers’ summer house on the shore of Lake Superior as a member of the family, as far as Mandy was concerned. At Lakeside, Miriam had always been free as her brother to ramble, to swim and dive, canoe and sail, wade and scramble up rock faces. As I was also taught to do, she went her own way, in trousers.

Walter imagined a life that might include both of them within one frame. If he couldn’t lead on the dance floor, he could in the woods. He bounded on his long legs up any hillside, leaned down to offer his hand. She required not help, but the very mastery she would resent. Though she loved to win at any sport, she couldn’t long tolerate a man she could beat. Still, here in the woods, she could take his offered hand. They could admire each other.

During the long northern evenings, the family sat on the screened porch and listened to the whine of mosquitoes pressing the mesh. They played cards, or Miriam strummed her uke while everybody sang along. Mandy folded Walter in so easily he almost felt he belonged.

At summer’s end, he would board a boat bound for South America, where Standard Oil was sending him for two years while Miriam stayed behind. My spirit of Adventure. He found himself a hundred times a day looking at Miriam, trying to memorize her face or capture a turn of phrase, one of those lines of poetry she was always dropping, an attitude of body. He had bought a used camera with his waiter’s wages, and he photographed her plying her paddle in the front of the canoe; lowering herself down a cliff face, rapt in concentration; wading into the lake; diving, laid out over the water—photos I thumb through, edges worn ragged. To me, they become documents of an obsession they can’t explain. Barely out of adolescence, at rest she is dreamy if not moody; in her sailor’s blouse or tank swimsuit she looks disheveled and a little dumpy.

Like me, he was trying to capture but also to decode. This life had made her, but into what? In the mornings, he awakened to the distant sound of her singing as she took an early walk along the shore.

At last, the days of rest ended. Walter was leaving for Venezuela; Miriam would head north on a field trip, having decided that she, too, like my mother and uncles after them, would become a geologist. On their last rambles, they talked of living in the wilderness as partners, looking together for oil to light cities, to drive civilization.

As Mandy stands on her toes to kiss her little girl goodbye, I feel something ending before it’s quite begun, while something else gains force and momentum just over the horizon. It was hard to say goodbye to Walter, but this farewell also sent a tremor of excitement through her. He would go forth in their stead and return with spoils and tales to tell. He had promised to write, and Mandy to reply. She had long since given up dreaming of her own journeys. She looked forward to following him in words.

Though she knew the cottage would be quiet, Mandy wasn’t prepared for the emptiness she felt as the screen door slapped shut. Tony and Lou were both out. Louis knew to stay out of her way. As she sat over her unread book on the porch, she mulled over her loose-endedness. Like any girl being wooed, she mustn’t write Walter until he had written her, but in the morning, she settled herself outside in the shade and began her letter to Miriam.

Last night when you left it almost seemed to me as though Brutus wanted to kiss me too—or was I mistaken? I should have been glad to if I had thought he really wanted me to….