Читать книгу Look Both Ways - Katharine Coles - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

INTERLUDE: WHAT I HAVE OF HER

FROM SARASOTA, SHE SENDS ME an embroidered shawl. A kimono. Velvet evening purses; suede gloves, elbow-length, the color of our eyes or the aquamarine in her last wedding set, the stone huge on my hand. Mandy’s Burmese sapphire and diamond ring mailed loose in an envelope. A batik, wayang figures intricate on a deep blue ground—

Something my mother wanted for herself, as perhaps she wanted all of it. Now in her eighties, Joan tells me her jewelry will come to me, every piece, and not her granddaughters; I will have the choice of everything, as she did not, as I never thought to give her—

Miriam’s wedding dress, which would not have fit my mother, who inherited Walter’s height. She sends them all while she is still alive, while she can see me in them, in the body like hers even smaller than it looks because it is straight and solid and broad shouldered, its blue gaze a reflection of her own. Having her eyes means not that I see like her, but that I look like her.

Having at last gotten Miriam’s permission to clear out the Sarasota house, my mother throws away pots with broken handles, bathing caps festooned with rotting rubber flowers, empty jars, every check Miriam’s mother Mandy, dead by then for thirty-five years, ever wrote. She boxes magazines and blenders with burned-out motors for Goodwill, but before my uncles can load them into the car my grandmother is hauling them back inside. At night, my mother lies in bed waiting for Miriam to shut off her lamp then rises to cram papers into trash bags and sneak them out to the curb, with no regard for history, reading nothing. In the morning, she finds Miriam in her nightgown on the front lawn, the papers strewn around her.

My mother saves for me Chinese rice bowls, hand-painted china, crystal cordial glasses the size of thimbles I am too thirsty to use. I am interested in how the past persists into the present. I’ll hang onto these things for anyone who might want them later.

I ask about the boxes of photographs. Women in long dresses and button boots picnicking beside a lake; men in twenties bathing suits, arrayed around my young grandmother, drinking champagne at a poolside shaded with palm trees. Visit after visit, I asked Miriam to label them. I might see a smile cross her face as she shuffled through the box and obediently applied her pencil to the backs of the snapshots, naming people, places I want to visit. She rarely answered my real question: who and what were they to her? One night, she showed me a ring—a square of jade set simply in gold, brought back from Batavia, now Jakarta. The photos’ ghosts had brought something to mind. She didn’t say what.

So many stories, so few told. Miriam had wanted to be a writer. For years, she sent me poems written in her youth, laden with flowers and turbulent skies and hints of romance, veiling as much as they revealed, poems I didn’t know how to read. There must be more. On the phone, listening to my mother describe a tea set she concedes is not my style, I think about my grandmother’s daydreaming, shuttered face. I say I want those poems, letters, journals, the old photos with names spidered in pencil on their backs: everything paper.

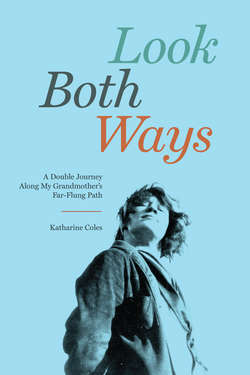

Miriam, Lakeside, Wisconsin, 1925

There is a pause on the line. My mother says, “I think we’ve thrown most of it away.”

Another pause, while I collect myself.

“Save what’s left,” I say. “If it’s okay with Grandmama.”

I imagine my grandmother looking out the sliding glass doors into her backyard toward the canal that travels to an ocean we have both crossed more than once. Her chin tilts up, her faded eyes seeing not this green Florida day but some distant morning streaming with sun, in which her own eyes are as brilliant as the tropical sky. Sixty years before, she wrote, There is always the chance that a diary might fall into hostile hands, before one’s death. Might not children or family be disillusioned if they read some of its pages? She always wanted to be read, though on her terms. The papers my mother tossed, Miriam recovered. A lifetime.

“I’ll have to ask her permission,” my mother says.

I have my permission. Miriam has known for years what I will do. Not now, but someday, when she is long gone. Even then, I will take my time.

My mother, she warns: “I fell in love a few times, you know.” And that is that.