Читать книгу Look Both Ways - Katharine Coles - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 4

COLOMBIAN HONEYMOON: FIRST THINGS

To speak is also to be.

LOUISE GLÜCK

Oct 5th 1927, New York

Just after sailing we received several Bon Voyage Telegrams, Flowers from the Davidsons, and a box of candy from Mrs. Wollaeger—our mother.

WALTER’S JOURNAL

AS THE METAPAN PULLED AWAY from the dock, Mrs. Walter K. Link stood at the rail, ready to become a woman geologist, sailing off the map. She leaned against her husband, feeling the thread holding her to her old self dissolve. The city blurred on the horizon.

She’d undertaken a series of first events, leaving herself behind again and again. After the ceremony in Mandy’s parlor, she stood in her bedroom for the last time as a virgin while Mandy straightened her collar and repaired her face. She stood for photographs on the porch then drove through fading light toward Chicago, leaving the hope chest with its cookbook behind. She was glad Walter couldn’t drive. She’d given herself to a stranger sleeping off bootlegged champagne in the passenger seat, but it was her foot pressing the accelerator.

To me the Palmer House Hotel with its frescoed lobby means old-fashioned elegance; to her it represented modern luxury. Mandy had warned her about the blood but not much else. As her husband labored over her body, Miriam sensed he was driven by a force beyond her. He’s awfully sweet to me in every way he knows how. It took Walter urgently, but it did not take her. She wrote Mandy, I weeped two nights in La Porte, and I could have a lot more times, but I thought I hadn’t better. During those long prenuptial evenings when they’d kissed into bruises, she’d felt—what? It was over quickly, and he was grateful. But she couldn’t wish to repeat it.

Imagine beginning with disappointment at the heart. I never thought I’d be such a baby. But the boat’s thrumming engines, New York a gleaming inspiration under the fall sun, came through him. He gets my goat quite often, but he doesn’t mean to. His long fingers circled her throat. She made herself stand still. I expect I’ll get over my touchiness. As you say, men are so dumb!

Hum of nerves. Soon, Walter would make their pitch to Argie, the grand idea, what she signed on for—as Chris and I made the pitch to our university, but with other offers in hand: they could have both of us or neither, at a time when such negotiations were still rare but beginning to succeed. Like Walter, Chris was the known and valuable quantity, I the one who needed to prove myself.

She believed Standard Oil couldn’t refuse a trained geologist willing to work for food and a mule. Could it? She was eager, fit as any boy, braver, anxious to test herself. But they had to wait, Walter said, until Argie could see she was a girl of another order.

To Mandy: P.S. She still obeys. I guess I must keep her a little longer.

Her first cocktail: a Manhattan, with its brilliant cherry. Her first ocean voyage. In Jamaica, her first tropical landing; a black policeman in his bright uniform. Yesterday, out of a clear sky, my “husband”(?) said, “Who said you weren’t good looking?” I haven’t quite recovered from the shock. Coming: her first view of the Panama Canal; cobbled streets; another continent.

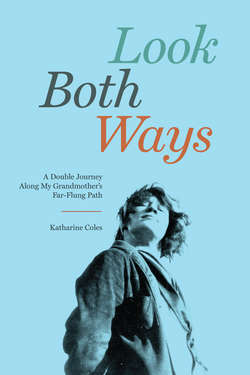

Bon voyage, 1927

At the Canal Zone, Mrs. Argabrite would embark on a Caribbean cruise, while Mrs. Link would continue with the men up the wild Magdalena. The couples played shuffleboard and walked the deck until cocktails. After dinner, they danced, Mrs. Link swinging with delight, Argie leaning into her. He said I should take Brutus in hand—women had lots more sense, and it was better in every way when the lady takes charge.

Her satin dress glowed phosphorescent green in the lantern light. Her first cigarette. Argie leaned over the flame as she exhaled, managing not to cough. What better time to ask? He said I had enough sense—well, quien sabe? Maybe he thought she was joking. Maybe her eyes were lit by her dress. Maybe he really imagined letting her come. I’m going along on the mule part of the trip, down to the llanos—that will take about a month. She was a different animal than Mrs. Argabrite. She had the same geology training he did. Maybe, under an ocean moon, he thought it could happen.

But even then, cocooned in smoke and moonlight, he hedged. Then Brutus will bring me back most of the way. A waste. When I leave the party, Brutus and Argie go up and down rivers, being poled painfully up, mapping as they go.

She believed she could do anything. Do I?

Filth, donkey trains, rotting plants and animals. No letters. I’m beginning to understand how much it means to hear from home down here. After four days in Cartagena, they boarded the F. Peres Rosa, a newly repurposed Mississippi paddle boat, for the trip up the Magdalena to Honda. There’s a barge on each side, and there’s cargo and cattle on them. Barefoot crew served dinner in the jackets they’d worn to load freight and clean the latrines. For days I saw a man standing around on the upper deck in a bath robe and pajamas. This man happened to be the captain. They passed machinery dumped in the river when the water was too low for heavy boats to clear the sandbars. But the trees pulsed with the calls of birds and frogs. One afternoon, a manatee, over ten feet long, smooth and breasted as a maiden, surfaced and swam alongside the boat, as curious about them as they were about her.

By the time I stand on the Magdalena’s banks, its manatees have been hunted to extinction, its fish poisoned by chemicals from agribusiness. The water flows with sewage and trash; the birds that once clattered in huge flocks above its surface have lost their homes to deforestation. Ambush and insurrection brought an end to large passenger boat service in the sixties; now, barges with bullet holes in their hulls deliver equipment to the oil refineries, and flimsy public chalupas transport a dozen people at a time. Yet the river surges and flows with unrelenting power.

I’ve been driven to the airport yet again, my husband this time made marginally less reluctant by a festival program with my name in it and a promise that I will be attended at all times. Flying in relative comfort into the Andes, I imagine how Miriam bathed with a sponge and dressed for dinner. For her the men became charming. You ought to see our parade—I carry the Flit gun ’cause the mosquitoes are bad, specially under the table, and Brutus carries a bottle of Worcestershire—we use that as disinfectant. Chicken, rice, soup seasoned by a grimy thumb. For dulce, a single prune. We all stared and then laughed till we cried. Even what she might have recognized became unfamiliar. They have a grande passion for playing a particularly tinny electric player piano, with rolls that have many more holes than they had originally—much of the beauty of such compositions as Collegiate is lost in silence. The berths were so tiny she and Walter had to bunk separately, a torment to him and a relief to her. The Company had sent a brand new mosquito bar.

Voyager: from voir, to see, through my eyes and theirs. Colombia is a rich in material resources of all kinds—Still they are extremely hostile toward the United States, whose capital wants to come in and exploit the country on a fair and square basis. To Walter, exploit is a technical term, without negative connotation.

After dinner, all but the few first-class passengers hung their hammocks on the open lower decks. While the river slipped through flat country, Argie ruminated his Havana. It was time for Walter to face reality. Less than a year before, he and Argie had entered the jungle fit and tough and emerged with infections, malaria, dysentery, having escaped smallpox, cholera, yellow fever. Absolutely no way to get out of here for help. The gusanos in Argie’s arm against the body of the beloved, smooth and clean and white. And what about her feminine malaise? If she ended up in a river (a bucking mule, a capsized raft), where caribe swarmed to a drop of blood? Indians, labor unrest, attacks. Pregnancy. Having no real idea, the men imagined the pack she couldn’t lift, the brush she couldn’t hack, the snake she’d be too frightened to behead. Staring at the murky water, I think what I can and can’t do, though I might want to. I am less at home in my body than either of them were, but I inherited their stamina; I can read a map, run a rapid, rope myself in to rappel a cliff.

Never mind that she can climb anything and swims better than both of them. What changed between those two men when she walked into the room? Fidelity. Priorities. Survival. They are crossing a river, these two men and that woman, and everything goes to hell: capsize, and the flesh eaters gather. They imagine having to save her and don’t question whom Walter would save if he had to choose. And if Argie had to decide between the woman whose right to be rescued was an invisible truth or the man on whom his safety relied? Reality, Argie reminded Walter, was where men died. Not a girl; not, if he could help it, on his watch. Better, he would argue, keep her out of the water.

Mommy, we’ve been married for six weeks and a day.

The two men sat smoking, looking toward a darkness behind which anything might be breathing, any weapon raised. Sometimes for 15 and 20 minutes at a time the boat will fight the current without budging an inch.

How could he not have known it would be this way?

Usually, people figure that when you get married it’s all over.

He wanted to live suspended in that bright bubble with Miriam. But no matter how hard the current fought them, they kept moving upriver.

Assume Mandy handed her daughter over, perhaps in the nick of time, a virgin. Walter made the same claim for himself. What he understood at twenty-five about his body, I will never know: what it could lift and climb and clear and sleep through, what parasites it attracted, in what convulsive purges it rid itself of poisons. Virgin or not, he knew every thing about it but one. If I could send my voice into the past, what would I say? I know this: during their wedding trip to La Porte, for the first six weeks Miriam didn’t write her mother, not once. Not that anything was wrong. And I think whatever Walter had taught himself, his focus now, when he entered a room with a bed and his new wife in it, should have been not on his own release, nor on learning one more thing about his own body, but on learning anything at all about a body like hers. Not even, after all, for Miriam—though imagine her sweet surprise. For himself alone, on the subject of female pleasure he should have been studious, as hardworking as he was on surveying, mapmaking, learning to wield his machete like a native and speak a Spanish his peons could understand. He’s most awfully sweet to me in every way he knows how. If he was going to leave her behind while he went into the bush, he should have known what she was missing, should have left her something to miss.

What makes a man?

He leaves me absolutely cold, physically.

Quien sabe?

The real vision only the men shared, exhilarating and bleak. Only they could enter it.

It’s a great life if you don’t weaken, Miriam wrote Mandy. But I won’t be weakening. No hay. Years later: He leaves me cold. He always has.

What might she have done? I have no idea.

Argie keeps reassuring us that we’re not going anywhere and when we get there we won’t see nothin’. Evenings beginning with cocktails, ending with brandy and bets over whether the captain would be wearing a jacket over his pajamas in the morning. We got to the next bend—it’s just like the rest. Her honeymoon. Brutus was just around to ask if I’d told you I smoked a cigarette.

When she began her journey, there was a point. She was headed into the bush.

But we keep right on traveling to nowhere—that’s our story and we stick by it.

Certainty, uncertainty. I got a big kick the first time I saw clouds below us. The prospect vanishing. If she had ridden with them down into the llanos, would she have become another woman altogether? Would my mother, would I?

I am in Colombia at last, for the International Poetry Festival in Medellín, founded in the nineties in response to the violence that had blown that city into legend. Before I go, Chris emails me links to websites about kidnappings, traffic, and cartels; I reply with articles about the museum, the botanical gardens, restaurants. In the twenties, Medellín was a village too small to mention, one valley west of the Magdalena; now, it rages with traffic, and its air thickens. In 1802, Alexander von Humboldt wrote, “the whole province of Antioquia is surrounded by mountains so difficult to pass that they who dislike entrusting themselves to the skill of a [human] bearer … must relinquish all thoughts of leaving the country.” Improbably, then, my grandfather traveled them by mule; now, when my host Jacqui and I visit the Parque Arví, a tram sails us up toward the Aburrá Valley over slums precariously perched where Walter must have dismounted to let the mule pick her own way down the mountain.

In the late twenties, some factions wanted to nationalize oil production. It will drive out all the oil companies, whose gated compounds lined the river. Talking late into the night with Colombian poets, I hesitantly tell them about my grandfather, and even now they set to re-arguing the politics. Some think the country should have struck a deal to take advantage of the U.S. expertise Walter vaunted, agreeing that the Colombian government didn’t know how to manage the foreign-built refineries and Andean pipeline. Others sensibly question the good faith of the foreign companies. All of them believe that Pablo Escobar and the civil war, grinding at last to an end, were U.S. creations.

“The problem,” Pamela, a young comedian and connoisseur assures me over the best rum I’ve ever drunk, “is North Americans are stupid.” She pauses, a beat too long. “Not you.” I demur and, after consulting with her, order another round, while talk turns to Medellín. My translator, the poet George Angel, bemoans the city’s historical amnesia; they all lament its constant remaking, new buildings going up over old, though this, I have been finding, is the way of things.

If I thought I’d be able to slip free to wander the city, I was mistaken. Jacqui makes sure I don’t walk outside the hotel alone, even during the day, even in the restaurant and museum districts. She takes me by the hand like a child when we need to cross the street—a solicitude that makes me smile, thinking how Chris would approve, until one of the European poets—male, not American, not led by the hand—steps into the path of a taxi and is carried off with a broken leg to the hospital. This, aside from a stolen backpack, is the only incidente grave during the ten-day festival.

Now that she wouldn’t be riding along, Miriam half wanted the congress to nationalize oil and the expedition to fall through. I sympathize. I have reasons to be there, a job to perform. Another five months apart, and what would she do? Go home as a married woman? Sit in Bogotá, in the Hotel Europa’s tiny Deco lobby? Look for work? I’ve gathered that my spouse doesn’t exactly like the idea of keeping me here at $125 a month. For his own reasons, he’d brought her all this way. And.

Walter and Argie were as secretive and absorbed as lovers. While they were out making inquiries, she waited for invitations, for him to come home, for mail. If you address it to Bogota, it takes at least a week, and almost two. Occasionally, she went to the office with Walter and practiced typing letters while he vanished for some mysterious meeting. He left me to find my way home all alone. My sense of direction never fails me. Mountains looming on one side, river and valley on the other. In Bogotá, we will all find our ways.

For what had Miriam’s life equipped her? To be her husband’s partner, a geologist? I am going to set out on a job of typing for Argie, and earn me some money. Typing meant composing the report herself from Argie’s notes about oil laws. His name would appear at the top, put there by her fingers pounding the keys, an act of self-erasure to which I won’t give in.

For what had her life equipped her? Friday night was the big Armistice Day dance at the Anglo-American club; I had a wild time getting my husband into his boiled shirt. She danced twenty-one dances straight. Five were supposed to be with Brutus, but other fellows just took them away. Not for the first or last time, he smoked and watched her spin in the arms of other men. An Englishman taught her to tango. Did he imagine she would change?

At night, starting late, the poets dance cumbia and Colombian salsa, which I pick up on the fly. Like Walter, my husband doesn’t dance, but he is happy to know I get it out of my system without him. I learn to still my upper body and loosen my hips and legs, relaxing, when I have an able partner, into his hands. One young man dances so intensely I could almost fall in love—but he hands me on to a gallant and stately Macedonian poet, surprisingly masterful, and returns to his beautiful girlfriend, also thrilling to watch.

Days and evenings, I give readings at festival sites around town or further afield. One morning at the botanical garden, under a cacophony of birds, a woman gestures me over to sign her program, pointing at my photo, saying “Katarina?” and “Estados Unidos?”

Hospitably, her husband hands me an open bottle. The woman snatches it back, and for a moment I think I am off the hook, but after wiping the lip on her sleeve she returns it to me, smiling. My young escort, another Angel, watches to see what I’ll do. I drink, and the husband shakes my hand. Angel smiles.

Leaving Venezuela, Guasdualito, 1928

Dinners out, golf with borrowed clubs, horseback riding. He takes her by mule into the mountains and by train to see the Tequendama Falls twenty miles away—even today over two hours from Bogotá on landslide-prone mountain roads. They stay in the Hotel del Salto, then a recently converted mansion built into the cliff opposite the falls, which my taxi will approach through cloud forest on a road skirting a precipitous drop. The ornate building floats in rainbows; abandoned in the nineties, when the stench from the Bogotá River and the falls overwhelmed it, it has reopened as a museum. Dutiful, I tour the exhibit honoring botanist Aimé Bonpland, who explored the Andes with Humboldt. But, like them, I have come for the thrill of altitude, water tumbling four hundred feet. Then, the falls were pristine. Now, at their base, the river still foams lightly with raw sewage, though the smell has subsided.

First uncertainty wore on her, then certainty. Congress adjourned today. Walter still had his job.

What was there for her? She might become a governess. And Daddy, I’m learning to tell the difference between a Martini, a Manhattan, and one or two other cocktails.

Finally, he chose for her: the wild Magdalena, another tumult of water. Not allowed to travel with him, she would instead spend a week alone on the river, rescued from the danger she wanted and flung into the one she didn’t. This time, there would be no cabin for the American Senora; she would sleep on deck in a hammock, effects in a bundle beside her, diamond ring pinned inside her brassiere.

Walter and Argie accompanied her on the train from Bogotá to Girardot. At the dock, both kissed her. As the boat drifted out into the stream, the two men stood together and waved. She was rounding the first bend when they dropped their hands as one and turned away as if released.

Then she was gone, coursing through a gash in the jungle. From the boat, no letters. I know only what she told me at her dining-room table. Rapids pounding against the hull. Rusted arms and cogs of abandoned machinery rippling below the surface, more perilous than snags. An automobile, submerged. None of Argabrite’s jokes, no cocktails after dinner. Only the sternwheel turning. Her hammock cradled her above the deck; mosquitoes hit a constant note. One night, she jolted awake to a dark figure looming beside her. She sat up and spoke, and it moved away, silent, its face a shadow. Her hand moved to the strap of her brassiere.

Not long ago, when she was protecting the virginity that belonged to him, this would have been incomprehensible: Miriam, alone on the Magdalena, moving away at the speed of rushing water. She would remember it all her life, her first solo journey.

And Walter? At midnight, I awoke cold. The stars sparkled, and the waning moon was on the horizon. He was deep in love remembered and desired. She was still out of reach, but now, at last, a sure thing, safe the way he wanted her.

Last time, floods; this time, fire. The canteens are empty. Walter counted every swallow of water—every swallow without it. The entire country is illuminated by the hundreds of fires all around, burning off the grasses and timbers. The savannahs had that hopeless weird aspect. Along the trail, people asked for news, but Walter and Argie were subtle as thieves, pretending to be lost, looking for cattle, diamonds, anything but oil. Again, he wrote to bridge geography and time: a letter traversing both from his eye to Miriam’s, now to mine. In grass-fringed marshes birds thrummed and turtles wallowed; crocodiles, otters, the capybara, a bulbous-faced rodent as big as I am. This country is a country of extremes, and it takes hardy men to travel it. He wanted Miriam to long to be with him, to understand why she was instead back where she started, tucked up in Mandy’s house, which she had married him to escape. The trails are strewn with the bleached bones of cattle. The nights swarmed with mosquitos. The darned things could bite as well as sing. At bedtime, he burned off ticks with the ember from his cigarette.

The drive to Hispania, a mountain village with a tree-shaded square, takes three hours each way from Medellín, first through heavy city traffic, then over a treacherous summit, then down the other side in a barely controlled careen, a ride for which the new Apple Watch Chris has strapped to me credits me with 4,226 steps, though I sit the whole way. As usual, the van has no seat belts. Nokia cell phone, Treo, iPhone, watch—of all the devices he’s given me, this one lets me tell him I am thinking of him in a moment, without using keys or distracting myself. When I lay my fingers on the watch’s screen, it sends him my heartbeat, slightly elevated, by text; from his conference room, his comes back, a pink blob pulsing against my wrist.

A few miles from our destination, we meet a roadblock. Armed men pace each side of our van, peering through the windows at the motley group of poets and interpreters, all but me South American. I make the mistake of lifting my eyes at the wrong moment, my blue gaze meeting the eyes of a man who stops and barks in Spanish. Later, browsing Google images, I’m not sure if his uniform belongs to the army, the national police, or the FARC.

We’re waved over. Pamela and Jacqui jump from the van. “Poetas,” I hear them say, and “Hispania.” The man with the gun leans against my window, inches away, watching me through the glass. Too late, I keep my eyes lowered. Against the guide book’s instructions, I have my passport with me. If they find it, will they keep me there? Confiscate it? Let us go? I try to breathe.