Читать книгу Look Both Ways - Katharine Coles - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

THE VENEZUELA TRIANGLE: A COURTSHIP IN THREE (OR SO) VOICES

WALTER UNHINGED HIS LEGS and stretched them into the aisle of the tour bus, watching Liberty lift her torch, the ferry slipping toward Bedloe’s Island. The city I have paced from downtown to midtown, where I have run the park and along the river, read my poems in dive bars and fancy auditoriums, and dined in company and alone, rises over the city he sees, not quite erasing it. Now, sitting quietly in my seat, I strain to listen to the guide.

He had two ambitions: to make a name for himself at Standard Oil, and to make Miriam his wife. He had two years to succeed or let her go. Simple, except he couldn’t keep her attention when he was standing in front of her, and now he was gone.

Wall Street, Broadway. As my bus stalls in traffic I try to imagine how midtown looked when the elevator was only beginning to transform it. With him, I shift my eyes from concrete to words and back, scan lists of the equipment he needs. Log books. Plane table. A Brunton compass with a mirror in its cover; pocket transom; camera; alidade; barometer. He couldn’t have too many socks, though he didn’t yet know it, or too much tobacco. His father’s old shotgun for hunting; the revolver from army surplus. When he wasn’t shopping, he wrote Mandy, he would hang around the office making sure the big dogs saw him. He was going to do something to remember.

Who was he? Containing, I wonder, what romance, what forms of violence? His shirt pocket held those photos of Miriam at Lakeside in her bathing suit, laughing, her round hip cocked. Cradled in the branches of a tree, about to start singing. Launching off the pier in a twisting one-hand stand, the body wheeling around its axis, force a solid thing. Silhouetted against the brilliance of the water, her poise seems impossible. Looking at these beside the shots of him gazing always pensive and unsmiling at the camera, I remember that he was the beautiful one, whatever the family myth—the one who gave my mother her cheekbones and long-lashed eyes as well as her height. What, I wonder, made Miriam so vivid in person, so hard to turn away from? The photos can’t tell me; they can only hint.

He is being carried into his future. She is in flight. Ninety years later: she has fallen, gone to water and air; he is gone with their letters, almost all of them, in which words turned to ash, as fragile and temporary in the end as the text arriving from Chris on my iPhone. Where they crossed, I am left. In his eye, she balances on one hand, uncontainable. Yet, he caught her. The proof is in my hand.

Oil: slippery, evasive, mysterious as time, pooled underfoot, surfacing in a seep, rainbow-slicking a pond, blue flame on water; or exploding like the held breath of a whale, the flesh of whose ancestors it renders: plankton, algae, anything that floated and died eons ago. To become fossil then fuel, it must be sedimented over and cooked under pressure; must migrate, buoyant, through permeable rock until it encounters an opening it cannot escape, a trap, a pocket created through structure, stratigraphy, hydrography. A dome, an anticline, a fault, or a fold; unconformity, lens, reef, difference in water pressure, a tilt in the hydrocarbon-water contact. Following his lead, I read disturbing history, evidence the earth below us never was solid: even rock transfigures. Where there was once an ancient seabed, riverbed, lakebed, coral reef, water where things lived, there is now a peak, a basin, a jungle, a desert.

The company starts him in Venezuela’s Maracaibo Basin because he’s green and oil is everywhere, structure legible on the surface. In more challenging geographies, he’ll need intuition to follow structure underground; he will descend pits into the earth or drill down and bring a core up. Here, if he can’t find oil, he’s in the wrong job.

His mind is precise, I know, the mind of the scientist I own. I think as I begin that it’s without lyricism, without the will to transform, though he turns out to be as inventive in his way as any poet. The map he makes is a thumbprint or an echo; it has whorls and arrows. It won’t show you a town, a road, or a house, won’t take you to the nearest mall or tell you where a star snugs into constellation. It shows which fractures occurred in the Paleocene, the Eocene, the Oligocene; shows cleats and upthrows and sediment transport—space and time, what happened when. It is the after-the-fact report of catastrophe still in progress, which you follow to a conclusion: drill here.

I first met him when I was seven or eight, after he outran the Brazilian army and returned to the States. He and my mother reconnected, more or less, and every summer we visited La Porte’s swankiest neighborhood, the elegant house with a pool that he bought to prove to the town of his impoverished childhood he’d succeeded. Though he wasn’t any more interested in her children than he had been in his own, he organized cribbage tournaments for me and my brothers, his films flickering like memory on the screen in his vast study full of artifacts, including the ebony elephant family that now sits on the étagère in my living room, minus tiny ivory tusks.

Now, his letters to Mandy are in my hands. Unlike my grandmother, he would not have foreseen this, his words working their way into the contours of my mind, going subterranean. He writes of what he sees and does and thinks thereby keeping his friends acquainted and in touch with him. Mandy was right: before Walter set foot on the SS Carabobo, Miriam could have papered a wall with his inscrutable hand. If we do the same there will never be the strangeness and aloofness that so often develops when people are separated by long distances and unlike conditions. Letters arrived in thick bundles. Read one a day, Mandy commanded, and answer it; then she’d have a nice stack to send every Friday.

But Miriam didn’t follow him, not even in words, as I do. There was too much to fill her time. Whiff of apples and wood smoke. A trail under bare trees, a lively two-year-old who loved to run and Harry’s horse pounding at her heels, not quite able to catch her. She would see Harry again that night, staying out past the 9:00 p.m. bedtime Walter had appointed with Mandy’s blessing. I won’t have it. The next man you go out with as often as that you will be engaged to. She’d thought the time without Walter would pass slowly, but days ripped by as if a hard wind tore at them.

Dear Brutus. What could she write? Today, six dates, two with Harry. Mandy’s whisper in her ear. Remember that you are building your future in character, health, and intellect. But what girl wants to be a work in progress? She wanted to come into herself magically, as when the horse surged beneath her or she leapt from the diving board into perfect suspension: each choice committed her to something, but her body chose for her. Thinking got in the way.

Eighteen: like me, shutting the door on one boy and opening it to another, she couldn’t give up on anything. Was the fault in the self she knew, or that she didn’t know herself? Was there a difference?

Maracaibo now is urban sprawl, hotels and condos, blue lake bristling with oil rigs. Then, the town was small, isolated by water, the basin wild. In the wilderness, they had open-sided tents for cooking and eating, two more to house the white men, Walter Link, junior geologist reading comics sent by his sweetheart’s mother, and his boss, Krug, his nose in Green Mansions, that imperial romantic tragedy, which had been circulating the camps. Twenty-five Venezuelan peons lived under five small tents. Combination Spanish, Indian, Negro, and American, they were, according to Walter, an awful mess.

Even here, white men didn’t cook. Pots clattered; the smell of whatever meat Walter had bagged—rabbit, turkey, deer—filled the air. After snuffing the light, he lay in his hammock under his mosquito bar, protection against malaria, and drifted off wondering where her letters were. My Dear Mrs. Wollaeger, I wanted to write last nite, but I had rather a depressive feeling. Mail from the U.S. might get stuck in customs or lie dumped and forgotten in some dockside warehouse. The little wind-up Victrola he’d ordered might be anywhere. I wrote to Muckie cause I always do that. During the rains mail had to come by burro through thick cactus forest. Too often no letters meant Miriam hadn’t written. He wrote to her every day. Mandy he wrote as often as an ordinarily ardent suitor.

I imagine him then, as Mandy did, among Indians, Spaniards, more recently arrived Americans, Dutch, and English—each jostling for advantage in a land cash poor but rich in resources, especially oil, new to the politics of capitalism, primed for development. El Benemérito, the Worthy One; El Bagre, the Catfish: President Juan Vicente Gómez had complete power. The oilmen, American and European, offered cash then condemned corruption; they bought politicians, women, laborers, and treated them with contempt.

I see all this through the lens of his letters and very different politics, my imperfect hindsight on a history that hadn’t yet unfolded. By the time I consider following him to Venezuela and Colombia, Indian attacks have been replaced by guerilla raids and cartel murders; civil war rages in Colombia; kidnapping in both countries has become a thriving for-profit business. One article, “How to Keep Your Ignorant Ass from Getting Kidnapped in Colombia,” boils its advice down to “avoid Colombia.” The president of my university at the time, a former Bush State Department official, assures Chris that if I am kidnapped in Indonesia he’ll get me out, thus adding kidnapping to Chris’s list of worries. About Venezuela and Colombia, he declines to promise.

For now, not capitulating so much as sensible, I make no plans. But anything can change. Even the ground moves.

And Walter? The Americans down here are disgusting in every way—gambling, whoring, trading coin for pleasure. To him, their failure was domestic, in responsibility to their own families and ideals, not Venezuela or its people.

Lifting his letter to my nose, I can almost smell green damp, mud, and salt. Now that I have finished a letter to every one that I owe one to—perhaps I can slip one to you while the rest are not looking. Walter understood what I am learning: Mandy, tiny and formidable, like her daughter, like me, was a coquette, prepared to be charmed. She looked forward to his news of malaria and thieves and Indian raids next to complaints about socks or tobacco lost in the mail. She liked to be courted and teased. He told her about the six-foot rattler he’d beheaded, its skin now dried and tucked away. He gave mileage and coordinates. She knew more about his whereabouts than her daughter’s.

When she was done writing Walter, she wrote to Miriam. Precious Blessing. She’d had no letter from her daughter in three weeks. If I don’t hear from you tomorrow I’ll hit you. She was worried about Harry. And Blessing—if you will be as fine and big as Brutus and I know you are, everything else will take care of itself, and no one need worry.

Krug got the flu, then malaria. They loaded him onto a mule, and there was Walter, in the sticks, alone with 25 peons and a damned poor knowledge of Spanish. Every day, he cut trail with the laborers, slashing at fica with his machete, competing to set the pace, developing endurance for which he would become famous.

When they found a spot, he set up his plane table. On good days, they might get clear space for some long shots, a half or even three-quarters of a mile. Walter liked plotting points, feet and tenths of feet, and drawing lines to join them, everything extraneous vanishing. This was his chance. The big dogs were coming soon, and he was determined that his map, by a junior geologist working alone, would be better than any by the nearby teams. I am my own boss. At night he cleaned his pistol and counted bullets, tins of food, even pencils. Nothing would disappear on his watch. Then, he wrote letters.

Does he know yet his love is measured, increasing with distance? Will he ever?

Mandy sent the Saturday Evening Post with its article on Venezuela. A cake, tobacco, good socks. Walter kept telling her where he was. Native trails and jungle became roads and drilling sites. He imagined how it must have looked to the first geologists. I guess you can’t kill em. If they couldn’t lick that kind of work they wouldn’t be geologists.

To Walter, she wrote, Tell me what is in your mind. He told her so much already; couldn’t she guess the rest?

Like her, I read my way in. Thumb-worn photographs. An earth in flux.

He proposed first to Mandy, who could make things happen. I’m in love with her, Walter said to his candle’s flickering light while the cook crooned a song in Spanish. And she with me. Her letter beneath his elbow said so. With her journals before me, trying to follow the plot, I have my doubts. The force between them flickering. Everything could vanish. An engagement, not to be announced, but for you, and Mr. Wollaeger, Muckie and myself.

Now, he had better write to his girl.

Burro. Boat. Warehouse. Train. From the age of instant messaging, I count the time with him: up to four weeks for the letters to reach Milwaukee and Madison. As few as two. The same for a reply, if Miriam answered right away. When had she ever?

Week 1

Snow fell in the woods where Miriam’s skis and those of the young men chasing her made the only sounds under the wind. The wind swept her onto the frozen lake, her iceboat’s runners whispering s’s and k’s. Like Mandy, I search her letters for mention of Walter—the weekly calendar, even edited so Harry’s name appears only twice, took pages. Then there were the lists of needed clothes: blouses, stockings, another evening gown. Mommy, could I have a green one? She showed no sign of knowing the future was closing around her. Walter may have been strong, stalwart, romantic (those scorching letters!), quick for her. He was absent.

And Miriam knew what Mandy wanted to hear. Ooh! Oh! Oh!!! I got five letters and a postal card from Brutus! Maybe I wasn’t floating around on air!

There was nothing so perfect as their courtship.

Week 2

I wonder if you would mind if I got her a Hope Chest? She can sit on it and wander away a little farther ahead. Walter dreaming Miriam dreaming of him. As if she ever stayed still. The dark cloud of her head resting on hope. Stille Nacht.

Week 3

Two days after Christmas, his letter came. Miriam was still home, but Mandy read it twice before waking her. Tell me.

I am in love with Muckie and she with me. How could Miriam argue? She had felt the lure of the imagined figure alone under candlelight, tested the words, written them. While she cried, Mandy held her, told her everything will be jake.

Week 4

The day passed, a week. She returned to Madison. What would it take, to move herself to I will, from the present to the future? Barely nineteen. At her age, I was always, an old friend reminds me, trailing young men. And, she adds, I was oblivious. Still, in an age devoted to one-at-a-time, I’d had more serious beaux than she, and had tried them farther; I would get through as many again before the last. I had the freedom to make up my own mind, a well-equipped handbag, and time to choose. I was free even to choose none at all.

Mandy: I think we should put Brutus out of his uncertainty.

Miriam: Your letter was so cute. She couldn’t win. She spent two days in bed, until Mandy, determined, sent the cable. Loving good wishes, dear son.

Is that satisfactory? If it isn’t I’ll spank you—I still can and will. Mandy’s virtuosity, her fingers on every string, violently pulling. Her vicarious life, everything she had missed.

I have a particularly bad case of nostalgia—(see Webster)—as well as one of downright lonesomeness, and it is enough to make me weep buckets, or even barrels.

From I do to I will to I miss. Did she miss Walter or herself? Absolutely a man.

In a way I was sorry when I read your letter—sorry that you should suffer so, and then on the other hand I was glad because it really means that you love Brutus. Willful misreading, which I sometimes engage in myself. Before Miriam, a month of waiting for every year of her life. You have the nice little job of training his “Muckie” to be the very best kind of a wife and mother. What would a hope chest mean to her, with her single option? You can tell Brutus one nice new perfectly good settlement cookbook is already waiting. Later, Miriam disliked cooking so much she learned to hate to eat.

What would a hope chest, the idea of it, mean to Walter? A gift not to her but to himself, the first of many. Mandy wondered if he was safe, too cold or too warm, wet or dry, if the candlelight strained his eyes. I will be glad when I have had an answer to the cable.

Both writing to Walter, to each other, weaving the web of letters. Have you ever thought that you can say next year we are going to meet him in New York if all goes well? Two heads bent under separate lamps, one the head of a woman enthralled by love. She will keep his letters until she dies.

Week 5

The last envelope from New York held Mandy’s cable. Dear Mrs. Wollaeger. No. Dear Mandy. Again. Dear Mother. Two weeks to reach him. I will do the best I can to make myself fit for your little girl. I will do all things that are right for your sake. His heart, the beating of cicadas. Hers and mine too. He fell in love with rattlesnakes, mosquitoes, the gallant little mule who’d carried his thin slip of paper.

So be it. At school, Miriam’s room was her own, and her head, if not her hand. And she was working outside, surrounded by men, an exception. Now that you have taken up his line of work, you’ll be his companion in that too. On weekend field trips surveying in the country north of Madison, at Devil’s Lake reading layers and signs and fossils in boulders scoured by glaciers from the earth, she felt body and mind come together and focus nervy energy into ambition. My mother took the same courses in 1952, also driven by the need to prove herself. After them, I scale cliffs and examine outcrops, as if my untrained eyes will ever read rock; as if I will want to. Not even, I remind myself, quite the same rocks.

Miriam carried tripods, bent over her plane table. She let herself imagine working with Walter side by side, and he encouraged her. We all know that in many ways women are just as or more capable than men. But he didn’t think she might seek knowledge for her own use. There are so many women now that don’t even care what their husbands are doing.

The engagement was secret; nobody was to know. She only needed to be steady, while Harry and the other young geologists jostled to partner with her in the field.

At last Walter had received his Victrola and the Christmas box with its records. I could not have bought a better selection to suit my taste. Or his memory. Mandy had taken Miriam downtown to a studio and recorded her singing German songs he knew, songs in French he didn’t, serenading him through a disc and needle.

He worked to distract himself. He adopted a monkey and a fawn that followed him like a dog, nuzzling his hand. He took photographs. When we sit down after dinner to have a cigar and even a glass of beer we feel much like a bunch of highbrows and millionaires.

This is where I imagine myself as he imagined her: in the wilderness, but only so wild. Cheerful around camp, she did wifely chores. In the field, like Rima from Green Mansions, she followed him invisibly through the jungle, singing from the shadows of the towering Vochysia trees. Anyone could have guessed from her first appearance that Rima—female, alone, living in the forest—was doomed to be prey, though she was the ablest character in the book. I guess when we are married I can take her to most any place that is reasonable, and be sure that she is enjoying every bit of it.

I know what is the matter—you are changing from a girl into a woman and therefore the fears and the uncertainties. I went through the same ordeal myself. That passage, the dark study where Mandy’s father had said he was sending her dull brother to college, but for her finishing school would do. It seems so much simpler and easier to stay as one was. She remembered girlhood dances as the inside of a kaleidoscope moving fast.

What had she seen in Louis Wollaeger? A dreamer, so handsome, his letters all in German. I think of men I could have married for their beauty, the ones who wanted to take care of me—how many times a box I was happy to carry or a tool I was ready to use was simply lifted out of my hands, leaving them with nothing to do. For Mandy as for Miriam, marriage was an end for women, more than a beginning. They had no alternative. When Mandy’s clock ran down, Louis was there.

Even Walter wrote that he wanted Miriam to have dresses and dances to wear them to while she could. For a geologist is not always in places where there is even a slight amount of social life. Wishful thinking. I have always sort of dodged that part of life, and now I see that it should not be done.

He didn’t yet know what I know, what Mandy surely suspected. He’s a darned unselfish man.

He was only trying to keep her. Soon he would vanish into the unmapped borderlands between Venezuela and Colombia, where I will cross his shadow. The rivers were nearly dry. Boats went aground on sand bars. Strange whistles pierced the jungle; flocks of parrots flashed their wings over the river. At night, his tent was lit like a target. Reading, I am listening so hard I hear the sloths breathing. One evening, a rustle, a rush of air—an arrow thudded into one of the kitchen crates, its shaft still trembling when he got there, the cook on his knees. Walter pulled it from the soft wood, keeping the poison tip away from his hands. He felt alert and free. I don’t blame them. The bowman had targeted not the Americans but the Venezuelan who worked for them. It was always your own who disappointed you.

The Caribbean Petroleum men, the most uncivil white people, withheld promised maps, information, supplies. Territorial disputes between companies used to treating the land as if they owned it were heating up under the pressure of political change. Standard, too, was rushing to pull out as much oil as possible before the Colombian government yanked the concessions.

Even as he moved into the wilderness, he worried about Miriam, who tried not to think of him. Who would prepare her for the bridal chamber? To Mandy, he wrote, There will be many things now that Muckie will want to know, and that you have experienced.

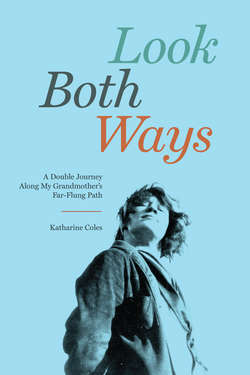

On September 5th, Walter got the package: the adjustable ring he had sent to get her size and a surprise, her engagement photograph. It took my breath away. She looks straight into the camera, not quite smiling, her chin lowered as if in challenge. A beautiful picture of a beautiful girl that is changing to a beautiful pure woman. Not really beautiful, I think. Smoldering, incendiary, mulishly angry at her mother. He wouldn’t be the only man to keep that photo near.

He had left her, a girl of eighteen, full of hope, dreams, and longing. Vanished, those letters, maybe half-imagined. What had he projected into them? What had she written? I myself have written I love you and in writing felt love move me. I’ve invented love and found someone to fit; I have been reinvented; I have surrendered the heavy box, the hammer, the drill, little pieces of myself.

His urgency. Light and shadow projected on a piece of paper. He wanted only to touch her. What could he write to her now? What to Mandy? I don’t want her to be married without any knowledge of my physical self. So many brides are terrified to death, purely because they have an unreasonable man that has no idea of the delicate soul of a pure virgin woman.

And her physical self? There must be a little dread that virgin girls have of certain things that come with married life. Soon, she must move from one state of being into another, like an excited electron or a truffle melting on the tongue. How would he, knowing no more than she, turn one kind of trembling into another? I will always try to control myself to have Muckie come to me. Suppose she tried to imagine desire, in a world that worked to prevent her doing so. She used to think it wrong for a woman to have passions and desires. Again, she and I part ways. I have sought pleasure through flush, boredom, fury, rekindling—I decided coolly when to get rid of my virginity, more burden than treasure, and with whom.

Might she have written passion and made it so?

So he wrote to his future mother-in-law, my great-grandmother. Mandy encouraged him—oh, desire—reading Green Mansions now, in bed all day. A girl is mistaken for a bird and then for a saint before she dies, a virgin. A certain kind of man, a certain kind of mother, at a certain time, might believe in worse fates. At eighty, my father, already slipping into dementia, confessed to me he wished my mother had liked sex more. I wonder what she’d been taught to imagine, beyond the technical details she passed on, dutifully, when I asked. Am I progress? Or did I just marry better? Wingbeat in hand, capture and release. Walter, who counted every bird he saw but named only the mockingbird. Who was he? Mother, I am banking on you to tell Muckie all about herself about men especially. Who was less qualified to teach Miriam—Mandy, who had taken no pleasure in her marriage; Walter, who would give none? I loved her for a long long time before I was ever conscious of her body at all. Don’t think about her body. I have to come to her clean. They knew less than nothing.

I wish you would give Muckie a little love as I would give it. Consider his temptations. Whether he had faltered. It can’t be done I know exactly, but she will now understand. Mandy’s own marriage bed, fruitful but I think hardly rich. Things would be different for Miriam and Walter. Things. She could have warned him.

If he could hear me now, what would I say? Who are you? I am looking, suddenly, not for her but for him.

A little love as I would give it. What we all have to learn, he should have made ready to teach her.

Three weeks later, Miriam moved her hand so her diamond caught the light, and people applauded her, as if she’d accomplished something.

The tripod, the alidade, the pick, the fossil. The pick raised and falling, its arc her body’s able motion. Metal against rock. Force up her arms. The rock giving, fragment by fragment. Her body’s motion, the rock giving.

I want to cut loose and run—to do things with just my own brains and nerve.

The ring took his whole savings.

I’m not good enough for him. When she wrote it, did she believe it? He lived for the wedding night; she dreaded it. I can only be free, and a virgin, once!

February. There are no maps. We will make our own. Reading, I am half exultant, half in cold terror, much like an infant. He and the senior geologist, Argabrite, Argie, would be mapping the remote Andes and, below, the llanos, the high grassy savannahs. I am in the very best of health and in good spirits. Walter packed light: paper, pens, pencils; seven photos of Miriam, including the engagement shot in its cardboard cover; her letters, lost to imagination; log books; gadgets. No Victrola. The music I will miss, but not as much as Muckie’s letters. Would Miriam stick? Please encourage my little girl. All she needs is to keep faith.

The note from Murphy came to her at home between semesters. Kid, may I write to you? A little thrill. I had a date to-nite. Oh my yes! Nothing like Walter’s letters, full of improving and informative anecdotes. I went with my sister. Is that O.K.? Nobody. A boy from school. I’d write a lot more if I knew it was all right. She’d told him she was engaged. She could hardly help it if he wrote her.

I wish I had a lot of money so that I could go wherever I wanted to. But after all, I couldn’t get away from myself. She knew this, at least.

Brutus is through his change already, Mandy wrote. He won’t be different in character. Violence, extremity—how did Mandy imagine they wouldn’t change him?

She said if I didn’t want to get married, it was the last thing she would let me do.

But if she decided to break it off, she must do so to his face, after his return.

I’m trying so hard to live up to her expectations.

The road to San Cristóbal followed the face of the mountain, carved from solid rock. On mule back, Walter and two peons followed Argabrite through clouds, able to see only the cliff face next to them, though the view must have been something. Almost on the Colombian border, San Cristóbal’s streets rose in dizzy switchbacks, houses clinging to the mountainside. There was no living to be made out of beauty and air—only out of what the white man would buy. Coffee, manpower, mules. I could have told him: Rima was a figment. Girls are dependent. They climbed into the paramo with its one tree, the red-trunked coloradito, a place so high and chill hummingbirds hibernate through every cold night. They tried to move south toward Bogotá, blocked by sheer drops into jungle, trees and shrubs and vines woven dense as a ball of yarn, like the landscape I sail over by tram in Medellín, above it all. I can’t say I am even tired as yet.

Birds he couldn’t name he left out of the log: cock-of-the-rock, crested quetzal, flowerpiercer, more species in Colombia than in any country on earth. I can’t resist details, whether birds he ignored, whose names I will record as a gift for my bird-loving husband, or numbers he hankered after, recording miles traveled, direction, altitude, the barometer his idea of traveling light. Fourteen kilometers, eight thousand feet. Twenty kilometers, three thousand feet down and six thousand up. I will have a lot of information concerning the country that is unknown now. He measured, therefore he was.

March. The rainy season would start in April. Political tensions, high since the U.S. had taken possession of Panama, ratcheted higher. The Colombian congress declared the subsoil property of the state. The team descended into the llanos toward the Casanare, following on the heels of a group of Texas prospectors, mapping feverishly. If they were lucky, the early rains would be sporadic; they might have twenty days before the soil was soaked and rivers grew impassable.

Four saddle mules, two pack mules, a beautiful bunch traversing screes and cliff faces where a slip on slick trails meant falling a thousand feet. The mules slid down this mountain on all fours.

April. The rivers are high. The Texan had set out with an elaborate string of mules loaded with camp chairs, cots, etc. They slipped discreetly in his wake, buying food and shelter at settlements along the way. We are sleeping in a rice hulling mill. There are pinching bugs and I woke in the night to find two bats in my hammock, a scorpion in my blanket, and a huge wood eating borer crawling over me.

Sure he was right, he had no idea what he was making. Would he have changed a thing? I envy him, though Miriam hadn’t written since January, though it would be months before Walter knew. Other things held her attention—Harry still; now Paul. He’s got a wonderful figure. Murphy loping beside her, asking if he could carry her books. Sweet Kid, he wrote her, in letters she kept but didn’t share. Rosebud.

What Walter wanted, what I want: pure exploration. The Guaicaramo seeps are huge hot water springs. A beautiful rain bow of oil shows for a long ways. On a rare clear evening, he looked out to see the llano light up at his feet, with millions of fire flies and biscucuias, a huge fire bug with two continuous luminous eyes and a tail light, circling over the plains like fords in a traffic jam.

The flatlands flooded. When we reach the Casanare we will have crossed every river in the entire State. Twenty-foot crocs, carnivorous fish. Just behind them, a pack team loaded with salt foundered in a current of electrons and went under. I have read articles where these eels have killed horses & cows, but never believed it. If they didn’t get out soon, they could be trapped for months. They were low on everything, even tobacco. A man can go without meals for a long time but a smoke must be had.

One of the Texan’s men died of pneumonia, and the rest pulled out. In Tauramena, the roof leaked, filling their hammocks with water. At midnight, Walter was wakened by a thump, a sick horse that had strolled over and fallen down against the door. The horse thinking this was the Padres house came around to see the Priest.

What to tell you and what to leave out? In a forest of words, every word draws me. Like Mandy, dying to follow, I am no better than he is, no more enlightened in my different moment, burning the oil he found. He travels a world of men, larger and freer than mine, his life built on the sweat and property of others, to which he feels entitled—a life I benefit from, one Miriam and I want. Except the red bugs that eat him, except for leeches and constant rain.

The day after they forded the Cauca, it rose behind them, impassable. In front of them, the Río Cusiana tore trees from its banks. We can’t move in any direction. Three crops in a row lost to flooding. Malaria, yellow fever. No food, no turkeys to shoot, not even yucca or plantános, though pack trains waited on the other side for the waters to recede. Abandoned houses, villages, and no growing boys or girls around with all the filled graveyards.

May 15th dawned clear and dry. The savannah lay covered with water. Walter had broken a tooth and feared an abscess. Argie had dysentery. Both suffered parasites and infected insect bites. They told us if it didn’t rain for two days we might be able to cross the Cusiana on a bull. They moved to a house on the riverbank. He and Argie reread all their magazines, including the ads. We have discussed the latest styles of men and women of which we know nothing and have solved all political problems of Colombia and the United States.

He was writing no letters, only the journal I hold. He thought of lamplight, a head bent over his words, not my head. Yesterday a man was swept away. He hardly knew what to tell Miriam. The body has been quite likely eaten by the various kinds of man-eating fishes that infest these rivers. Her letters were so worn they fell apart in his hands.

And her? All this, and she never wrote a word in her journal suggesting she might be worried or moved. Must I be reconciled to be the wife of a stranger?

She enrolled in an advanced course in topographic mapping, one of the first two women to take it, putting on knickerbockers and carrying her surveying rod into the northern woods. To guarantee their failure, the professor sent the women on a steep traverse, an area he wouldn’t have expected any student to finish. All day, she and Catherine hefted their equipment over boulders and up to the high ridges. By the time they returned to camp, well after nightfall, the professor was frantic. They had completed their map.

Back in Madison, Harry got on her nerves. He’s not worth it. Murphy set her nerves singing. He can be horrid. Paul. He wanted me to take his car. He says it’s “our” car, but I couldn’t.

Twenty. Afraid to be alone, not to be alone. I know.

All she needs is to keep faith.

Shhh, Mandy says. Come here.

One last dry night. Finally, they could ford the river and begin their climb, scaling rock stairways running a torrent of water, navigating huge boulders in the trail, everything you can think of that is bad. The men walked, letting the mules go ahead to find the best route. They are so tired now that they absolutely won’t touch corn.

Late May. The clouds dissolved. At ten thousand feet and counting, he ignored the cliff shearing fifteen hundred feet down and looked out at the vista, a green wave falling, and thought no longer about an ethereal bird girl but about flesh and blood he wanted. When they reached Bogotá, he would mail the letter he was writing in his head. I am darned glad I come from the U.S.A. and that I will have a girl that comes from there.

Mandy’s fingers curled in Miriam’s hair; Miriam’s brow on her mother’s shoulder. A mother’s love, a lover’s desire. I only wish now that you will always reassure my little girl for me. Shhh, Mandy says. Come here. She folds his Muckie into her arms, her grip too tight for Miriam to loosen, and keeps her there. I want to bum. She never will. She can’t go anywhere but deeper into the interior, where she sees what she thinks is his face.

In Bogotá, he went straight to the office and cabled Miriam. From the company, he wanted two things: a raise and permission to go home and marry her.

Her letters are just about worn out. He had his tooth repaired; he’d lost twenty pounds. A nurse sliced two gusanos from Argabrite’s arm. The larvae were as large as large beans.

People. Hotels, with almost all a poor sucker of a rock hound could want in the line of comfort. Gambling, women, bars. In field clothes and boots, he sat down for a drink with Mr. Shaw, their chief, come by boat up the hard rapids of the Magdalena just to see him. He ordered scotch and took a piece of ice in his mouth, letting it sit on his tongue.

The world of scotch and ice was the world of company politics; then as now, company politics were international politics. Walter had entered the mountains of Venezuela an employee of Standard Oil of Venezuela; he emerged from the Colombian jungles working for the South American Exploration Company, a camouflage division for Standard Oil of New Jersey. Mr. Shaw offered him a promotion. But Walter pulled out Miriam’s photograph.

Another round, then. The beauty of the bride.

Having refused the job, he set out to prove he had loyalty and guile as well as strength, endurance, and accuracy. He took advantage of being a stranger to get the jump on these birds, asking questions in bars, visiting the Texan, reading his maps upside-down. I have also the boundaries of the Jones, Celig concessions near Guaicarana.

He waited for instructions from New York to make their way upriver. He cabled, I wish we were already married. He tried to remember how New York had looked from the bus—all those people—but no doubt it had changed. He kept seeing Miriam’s face on the window, adrift between him and the grand avenues.

How could she be sure, after all that time, that he loved her, and not some idea of her?

At the end of June, Walter at last got his release. He journeyed down the mad Magdalena and overland by rail and burro and car, sailed north on seas calm as the lakes back home. His environment won’t have any particular effect on him. The mental stimulus and reaction comes almost wholly from you. The morning they were to dock in New York, he took from his trunk the town clothes he’d set aside two years before. They sat strangely against his skin; his soft city shoes felt as if they might dissolve. Over the harbor, the statue lifted her torch before a skyline I wouldn’t recognize. He stepped off the ship into early fall sunshine, scarcely knowing how to be, in this clean-and-pressed crowd, a man any longer. Then he saw her, shading her eyes with gloved hands. Almost two years between them reduced to a narrowing strip of water: he was lean and brown and quieter than ever; she, also thinner, looked at once like the girl he knew and like a woman with a secret life of her own.

He had dreamed of climbing into the taxi with Miriam and driving up Broadway, pointing out the sites, but with her newly bobbed hair and scarlet lips, slightly open as the taxi labored toward Times Square in a cloud of burning oil, she was both more and less than the girl he’d dreamed up while cicadas beat their wings with desire in the jungle. Her small hand with his diamond on it sat placidly in his large one, but he had spent so much time refining her image to his need that he hardly knew her. He had used all his patience to get here. She looked at everything but him.

They went to their separate rooms to dress for dinner. In his wardrobe hung starched shirts and neckties and suits sent from La Porte, his mother and sisters meeting her on the platform in Chicago to pass the cases when she changed trains. Those clothes still held the old shape of his body, but his field trunk contained his real life, the one he had carried out of the jungle, without small talk or evening kits, its smell when he opened it damp and dark and mineral. Under his boots, green with mold, was a wood box holding the army revolver he had bought in New York two years before and carried into the bush. He had put it away cleaned and oiled in Barranquilla; now, he pushed bullets into the chamber with the flat of his thumb. As dusk fell, he washed, shaved, and put on a boiled shirt and his dinner jacket. He tucked the gun in the back of his waistband and rode the elevator up to knock on Miriam’s door.

Under his gaze, she moved aside, not meeting his eyes. When he showed her the gun, she backed herself up against the window, darkness over her head and city lights spread out below her like a train of sparks. To set her mind at ease, he raised the gun and pointed it at his own head. He imagined being the fellow down below, looking up at her silhouette against the light: bare swimmer’s shoulders, the glimmer of pale blue silk and pearl. The glass must have been cold. She should have had a wrap. He needed her to understand.

If I invent details—pearls, silk, the man under the window—it is because I want to linger. I, too, have been spellbound, overtaken by a man’s love not for me but for some idea. How do I know all my beaux would miss me if I suddenly disappeared? Would he pull the trigger? Brutus might. She’d meant to marry him. If she had to throw herself over some cliff, why not this one? Then she’d seen how, after all, he was still only Walter, harder and more sure but somehow the same. His environment won’t have any particular effect on him. Then he raised the pistol, calm, and he wasn’t the same at all. He was larger, lit with violence. He had lived only for her. He wanted her to come with him into the bush.

Cockroaches, scorpions, vampire bats. Hundreds of singing frogs, night birds, monkeys, and parrots. There is no sign she had imagined it, but now there was the pistol. Who was she, who couldn’t say she’d really loved anyone, to deny this? Hadn’t she always been waiting for such a One? Always her question, and for too long my own—not, do I love, but rather, Does he love me? How much? His finger on the trigger, he, too, became an idea. You never have loved me—but that she would write later. Waving the revolver around your head. Most of her letters to him are gone; this one survives because she never sent it. Now, what could she do? She stepped away from the window. Arrows tipped with poison. Electric eels; the man-eating caribe. A man different than the pacifist I would eventually choose for myself, holding a pistol as if he knew exactly how to use it, in a room that no longer exists, in a vanished world.

She walked into his arms. The relief that flooded her when he lowered the gun and set it on the table felt like nothing so much as love.

Murphy: Sweet Rosebud, I’m still weak. She had written she was at the lake. Sweet kid, why didn’t you tell me Brutus was there? It was such a blow when he walked in. Had she expected him to drive all that way to see her? Please, please excuse me for acting so insane.

Once you’d been shot at by Indians, a boy like Murphy held no terror. Once you’d held the gun to your own head and come out alive with what you wanted. Walter shook Murphy’s hand, sat down on the sofa, and went to work on his pipe as if tamping tobacco was the only thing on his mind.

The man with three initials, who wanted to give them to her: Mrs. P.E.M. Purcell. I just finished playing Pretty Lips. Please! I’m begging. She didn’t answer.

Harry: His letter waited in Milwaukee. I’ve been in hell. Handsome Harry, who had tried not to love her. It’s easier to jump up into an airship from the ground. I’ll always wait now. These are the love letters she kept—the ones from men she didn’t marry.

Mandy smoothed Miriam’s veil. Off-white lace and satin, seed pearls, white roses. Now, instead of looking straight at the camera, Miriam softened her face and dropped her lashes, gazing modest and maidenly at a place beyond the frame, as if she saw something there that was only for her, or as if to hide from us the look in her eyes.