Читать книгу Pride & Joy - Kathleen Archambeau - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

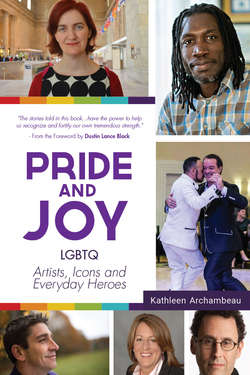

ОглавлениеBill T. Jones, two-time Tony Award-winning choreographer, MacArthur “Genius,” National Medal of Arts and Doris Duke Artist Award-winner, crosses barriers to create works that tackle the BIG subjects: love, loneliness, identity, marginalization, loss of control, meaning, illness, death, and spiritual triumph. Jones is fearless while being afraid. “I think it takes courage to be alive as a sensitive person, particularly in mid-life if you’ve been a performer as I have where your body is your stock and trade, your calling card and then your body is changing “It’s a crap shoot. It’s a beautiful crap shoot. But, it’s a crap shoot,” he said.

Bill T. Jones and Bjorn Amelan, together since first meeting in Paris, Feb. 16, 1992 Partners and arts collaborators Bjorn Amelan is a set designer for NY LiveArts Elisa Rolle, LiveJournal

Jones was not always a dancer. He began life in 1952 in Bunnell, Florida, the tenth of twelve children born to migrant potato pickers who moved permanently to upstate New York, where Bill spent the bulk of his childhood. A theater major on an athletic scholarship to State University of New York in Binghamton, he found his calling when he wandered into an African dance class. The smell of sweat and dynamic pounding on the floor captivated him. Soon, he was eschewing track practice to take dance classes. There he met Arnie Zane, a Jewish-Italian white gay man, a SUNY graduate returning to study photography, who ventured into dance classes with Bill. That began a seventeen-year life and avant-garde modern dance partnership that ended with Zane’s death at age thirty-nine as a result of AIDS.

The boundary-crossing work begun with the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company continues to this day with Jones’ world premiere, Analogy/Dora: Tramontane. For this work, Jones drew upon ten years of interviewing Holocaust survivor Dora Amelan, the mother of his husband and life partner of twenty-four years, Bjorn Amelan, a Jewish French-Israeli sculptor and set designer. The new work depicts one refugee’s journey in the midst of crisis. “Dora Amelan is a family member whom I love, not a newspaper article “Her experience opened history to me in a way the media cannot,” Jones explained. That experience opens audiences and dance companies alike to the theme of Holocaust, not as an historical footnote, but as a very real and ongoing human crisis.

Still/Here remains one of the most controversial dance works created by Jones. He used his own experience of living with HIV since his diagnosis in 1986, and gathered non-dancers from around the country, working with them to express their feelings about living with life-threatening illness. He used that material—actual non-dancers and their stories—to meld with his dance company to create a dramatic paean to life. Still represented the quiet moment in response to diagnosis, and Here represented the dramatic sense of being present in the moment that often comes with the urgency of being told one has a life-threatening illness. Jones courageously told the untold stories of the many nameless life-threateningly ill around the country in a way that connected audiences to their own mortality, and stirred such controversy that one New York critic panned the work without even seeing it. It led to deeper questions: “What is the meaning of life? What brings meaning to your life? What do you love? Now, go do that.”

Some of Jones’ most emblematic works have occurred off Broadway. When Arnie Zane died, Jones danced Absence (1989), one of the most exquisite expressions of love and loss ever to grace the stage. Aged thirty-seven, he danced a duet with his now invisible partner, expressing in movement the inexpressible. “It was a gift actually. Absence connected me to the big spiritual existential questions about the nature of death, about love,” Jones said.

However, the Broadway stage is where Bill T. Jones has garnered his widest audience. In 2007, he won the Tony Award for Best Choreography for the musical Spring Awakening, the story of a nineteenth-century German schoolgirl coming of age and the collective rebellion of German teens in an era of repression and structure. In The Bitch of Living number shown at the 2007 Tony Awards, worldwide television audiences got to see the genius of Jones. He took schoolboy adolescents in laced up boots and uniforms and created a dance where they stomp and yell and break out of the strictures of their constrained upbringing. How did Jones relate to a culture so different from his own? “I didn’t have to go back to the nineteenth century. Right, I’m a stomper, if that’s what you mean…I think the Coming of Age story is told again and again in popular media “I did it with gestures and they turned out to be pretty universal, actually.”

Bjorn Amelan and Bill T. Jones, Aberdeen Restaurant, White Plains, NY.

Photo by Chester Higgins Jr., NY Times

In 2010, American audiences saw and could begin to understand the experiences of African musicians and activists by looking at the world through Fela Kuti’s eyes. Jones again succeeded in transporting mostly white middle class American audiences to conservative, corrupt Nigeria to meet Fela!, the Afrobeat musician and activist who was jailed nearly 200 times in his young life and had nearly every bone in his body broken by a repressive military regime. The thunder and pulse of Jones’ second Tony Award-winning musical pushed audiences to stand up in the middle of the production and move their hips to Fela’s “The Clock,” adapted from Fela Kuti’s stage performances. “There is a revolt in the way one lives in one’s body and dancing in public, making yourself vulnerable to be looked at, to be seen” is revolutionary, Jones explained. This short scene in the musical has disrupted the theater experience forever. And, as Bill says, “the theater needs to be disrupted.”

Exposing his own vulnerability is what endears Bill T. Jones to his young dancers, fellow choreographers, and wide audiences. Jones is seizing new opportunities to disseminate the language of the body even as his body ages, even as he is surrounded by the speedy, lithe, flexible pantheon of young dancers in his company. In 2011, Jones took on the great challenge of merging a dance company, the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, and a dance movement incubator space, the Dance Theater Workshop of New York, to create an entirely new body arts organization, the New York Live Arts nonprofit, set in the heart of Chelsea. The unprecedented collaboration that created NY Live Arts, a service organization, has an Artistic Director who is a working choreographer with a resident company. Is Jones afraid of the responsibility as Cofounder and Artistic Director, of filling the 20,000-square foot home that houses a 184-seat theater and two 1,200-square foot studio spaces? You bet he is, but that has never stopped him from proceeding to create a place where “thinking and movement meet the future.”

Bill T. Jones receives the 2013 National Medal of Arts from President Barack Obama.

Photo by Pete Souza

Determined to expose a broader range of audiences, particularly people of color, Jones has always been a “Black male in the white avant-garde his whole career. Don’t get me wrong: I run a theater. How do we keep all the critics of the NY Times and middle class audiences happy and, at the same time, get people in there who want to bop along to Hamilton?…People who look very different than what we’re up against in the downtown New York City art world “This country is so craven and profit-driven that when true art does not have a market value, people shun it. Every one of us whom I call cultural workers—how do we get the attention of an ever more attention-deficit population? I hope audiences will come closer to their own processes and realize they’re collaborators in all cultural events, particularly in the theater. They are expected to be alive and very much aware of the myriad of things occurring on stage and the myriad of things occurring inside of themselves.”

How does he work with NY Live Arts set designer and husband, Bjorn Amelan, and then go back home to Valley Cottage without feeling compressed? “Arnie Zane and I built the dance company and he and I were companions for seventeen years until he died. I’ve never done it any other way. I can’t even imagine a relationship where you go home and where you talk about your work that day at the stock market and I talk about my work that day at the studio “I don’t think that the separation between life and art exists in that way.”

Analogy/ Dora: Tramontane is Jones’ latest work and is part of a trilogy. Part II, Analogy/Lance: Pretty aka The Escape Artist and Part III, Analogy/ Ambrose: The Emigrant will be performed in 2016 and 2017. The third work uses the German novel, The Emigrants by W.G. Sebald, as its point of departure. Jones will continue to perform Story/Time, inspired by John Cage’s 1959 Indeterminacy, a compendium of 180 one-minute everyday Bill T. Jones stories, seventy of which are recited on stage with young dancers swirling all around him.

The best advice that guides him today came early on from his mother, who had seen “a vale of sorrows” and said to him, “Life ain’t nothin’ child than putting one foot in front of another.” Bill T. Jones has done just that and more in his creative life.

“This country is so craven and profit-driven that when true art does not have a market value, people shun it. Every one of us whom I call cultural workers—how do we get the attention of an ever more attention-deficit population? “

Bill T. Jones