Читать книгу Bali By Design - Kim Inglis - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE NEW BALI

For first time visitors, repeat guests, those that have made Bali their home, and the Balinese themselves, there is no denying the rapid changes that have taken place on the island in the past few years. What was once a romantic, cultural getaway with rice field and temple predominating has transformed into a thrusting metropolis, especially in the built-up southern areas. Bali’s slow pace of life—in the main tourist and residential centers anyway—is a thing of the past.

As with all change, there are positives and negatives. Increased prosperity is certainly a plus point; traffic jams, pollution and unplanned development are sad reminders of the cost of “progress”. Yet, amongst the mayhem, you can still find the rich landscape and culture that has beguiled visitors for centuries. It continues to draw outsiders—many of whom are building extraordinary homes.

After a year of research, we’ve come to the conclusion that the Bali brand is as strong as ever. Because the island is welcoming, the people some of the most beautiful on the planet, the climate salubrious, the economy buoyant—foreign investment continues, grows and multiplies. More and more outsiders—from Australia, other parts of Asia, Europe and even America—are making Bali their home, and many more are investing in villas suitable for the holiday rental market.

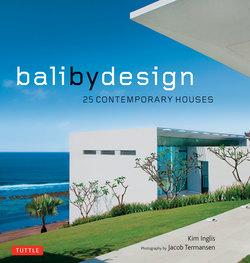

For the most part, this book concentrates on homes, although there are one or two rentals as well. Almost all are newly built residences. We consider them the cream of the crop, representative of the exciting new architectural directions that Bali is witness to, yet by no means the norm.

We’ve left out the terraced villas, the cheek-by-jowl estates, the ribbon developments, the small condos; we’re showcasing only extremely high-end, innovative properties. Some are in the countryside—by the sea, in the hills, overlooking rice paddies—but many are in built-up areas as is increasingly common. The homes may not have the picture postcard views of the past, in fact they’re more than likely to be inward looking, but they are noteworthy nonetheless.

Each home has been chosen because of its excellent architecture, innovative design features, and cutting-edge interiors, but also because each is very different from the next. Variety is the key here; no cookie-cutter copies thank you very much. We want you to drool over their beauty in the same way we did, read about some of the new materials and methods used, maybe incorporate some of the ideas into your own homes. We’re grateful to have been invited in—and we hope you’ll find the houses as extraordinary as we have done.

Style, Substance and Sustainability

So what are the major changes in architecture and design in Bali? Firstly, an increased level of sophistication is increasingly sought—and supplied. Craftsmanship has always been one of Bali’s strengths, but it has more often than not remained in the vernacular. Now, we see high-end finishing in furniture and artefacts, as well as surface embellishment and building materials. Modern imported kitchen equipment, technical know-how in lighting, plumbing and ventilation, high quality materials—all are becoming readily available in Bali.

Nestling in a sculptural, yet lush, bamboo garden is a seemingly floating European-style, flat-roofed rectangular prism set on piles. Designed by i-LAB Architecture, it is part of a complex that also comprises recycled Javanese structures—a wonderful combo of new and old.

The use of concrete has increased exponentially. Not only does concrete evoke a feeling of serenity and calm, it is cooling underfoot. Traditional building materials such as alangalang for roofing are being replaced by wood shingles—and, more often, flat roofs. Often such roofs sport plantings or water features to help with natural cooling. Easily sourced local stones—andesite, paras, palimanan—are still widely used, but often the cut is more modern, the finishing more streamlined.

Sustainability is another factor. A lot of high-end clients want to impact as little as possible on the natural environment, so they often request a low-energy design that reduces the use of air-conditioning and returns to traditional natural ventilation techniques. Many of the architects featured in this book conduct an environmental impact assessment before they start a project and try to go as green as they can: Using non-toxic paints, solar energy, water catchment and recycling techniques, as well as trying to adhere as closely as possible to the natural contours of the land, are some of the methods they employ.

Many suggest that such practices are pure common sense. Gary Fell of Gfab, a firm that espouses a rigorous modernity in its aesthetic, believes passionately that buildings should be “married” to their environment going so far as to semi-bury buildings especially if they are on steeply sloping sites (see pages 174–179). Cutting down on air-con is simply practical, he says. “Why on earth wouldn’t one exploit air flow through a planning mechanism?” he exclaims. “Why would one park a roof in that view for Pete’s sake? (ipso facto use a roof garden, therefore flat roof).” Careful consideration of materials should be the job of every architect, but as he wryly notes: “How many full glass shop fronts in brilliant sunlight do you see?”

Valentina Audrito, an Italian architect with her own company Word of Mouth, echoes Gary’s sentiments. In one recent project she placed landscaped boxes and reflecting lily pools on flat roofs to reduce air-con consumption and increase the cooling effect below. And because the house was three kilometers away from the nearest electricity source, she designed a power system based on a combination of solar panels and batteries supported by a generator. “Cutting air-con is a priority,” Valentina states firmly.

Johnny Kember of KplusK Associates, a practice in Hong Kong, states that it is every architect’s responsibility to explore sustainable and environmentally friendly building methods. After doing some research, he has been amazed at how many ways there are to produce low-carbon footprint buildings—and he has included a few in his iconic design on the Bukit (see pages 96–103). He sees many buildings that are almost entirely self sustaining in terms of their energy and water usage—and believes that this is the way forward for the future.

Designed by Balinese architect Yoka Sara, this home combines traditional materials with the ultra modern. This sculptural oval staircase rising up from a reflecting pool is a case in point: Made from concrete and steel with timber treads, it features a curving bamboo balustrade.

Naturally, this is not the norm. In Bali, there are few building restrictions and the onus is on clients and architects to try to do the “right thing”. Ross Peat of Seriously Designed laments the over-crowding and the lack of infrastructure planning, as well as the difficulty of acquiring electricity and water, but notes: “All that being said, there are some amazing buildings being designed and built in Bali.” Nevertheless, he goes on to add: “It is clear that the building regulations are far from conducive to people’s privacy as you do see structures being built too close to their boundaries and often overlooking other properties.”

As such, Ross often turns houses in on themselves, replacing external viewpoints with internal courts and secluded gardens. “You can’t count on the view for ever,” he maintains, “so in most cases I design to have the view internally. I also try to have generous open spaces both in and outdoor, giving a feeling of a seamless transition between the outdoor and indoor areas.” See his own home on pages 138–143, a fine example of easeful tropical living.

This idea of blurring boundaries between indoor and outdoor harks back to earlier pavilion-style living in wall-less or semi-walled structures, a type of style that we have come to term “Bali-style”. In fact, this type of structure should really be named “resort-style” or something to that effect, as it was pioneered by early resort architects such as Peter Muller at the Kayu Aya Hotel (now the Oberoi) and Amandari. He, in turn, was influenced by tropical maestro, Geoffrey Bawa. The style bears little relation to indigenous Balinese building traditions—with the exception perhaps of the open-sided wantilan and balé.

Large entertaining spaces were a specific request from the owner of this spacious home. Ross Peat of Seriously Designed also made sure that only the highest quality materials were used, as evidenced by this Statuario marble show kitchen.

Today’s villas have eschewed the dark wood and pitched roofs for something very different to these earlier prototypes: The new wave of architecture is more lightweight, open-plan, more streamlined, definitely more Western in form. There may be a sense of place, an interpretation of Balinese courtyard living, but visually these new residences are nothing like their older counterparts. Balinese architect Yoka Sara says there may be some reference to Balinese roots and culture in house design, but you have to really look to see the parallels. The days of having a rice granary or lumbung as a spare room are well and truly over, he believes.

Instead, he tends to immerse himself in the landscape to try to “improve and emphasize natural elements and surroundings” within a modern architectural vocabulary. Only by imagining the movement and sequence of spaces on a site, can he “build up the emotion and set the living spaces”. As with Gary Fell and Johnny Kember, he uses the natural contours of the land, the way that the breeze blows, the direction of natural light to articulate the spaces—and these elements usually result in a reduction in air-con and power. One of his recent designs, Kayu Aga (see pages 74–79) is a case in point.

Another reason that architects are looking inward is that plots are becoming smaller. What were once small settlements or villages are turning into towns and areas of rice field are being erased. For example, in Seminyak land is very expensive nowadays, so architects are increasingly looking for innovative ways to counteract the limitations. In one of Gary Fell’s new projects, he “effectively stands the villa on its head” placing the utilities and bedrooms at the front of the house, ie on the lower levels, and putting the living areas and pool on the roof to access views.

In another project, Swiss designer Renato Guillermo de Pola incorporates a central atrium, complete with glass pyramid roof and internal plantings, in the center of his house. For all practical purposes, this is his “garden”, with open-plan spaces clustering around (see pages 50–55). Built along the lines of a New York loft with semi-industrial materials and an urban aesthetic, it is the exact opposite of the trad Bali villa with rice field view.

Nevertheless, we do showcase plenty of homes in remote, rural areas where the houses work consciously with their tropical environment, be they overtly modern or vernacular in inspiration. The use of water features (often nowadays found on roofs), the melding of timber and stone, and the idea of bringing the landscape to bear on the interior are all perfected in different ways. Many of the houses sport clean lines, sculpted shapes and are modernist in style, but there is some conservation and re-use of existing architecture and materials, mostly observed in the recycling of wood and the use of entire wooden structures. The residence featured on pages 56–65, comprising a number of joglos and gladags, traditional wooden tructures from Java, as well as a Sumatran house, counters vernacular architecture with fashion-forward interiors that would not be out of place in a chic Parisian apartment or a London townhouse.

A New Wave of Interior Design

Bali has long been renowned as a center of creativity, with a profound artistic tradition that has inspired a proliferation of cottage industries all over the island. Every village has an artist, a sculptor, a carver—often scores of them. As such, it has long been a magnet for talented creatives from abroad.

Yet the last few years has seen a change in emphasis and scale. The small ateliers and individual artists of the 20th century have burgeoned into 21st-century export-driven factories with large showrooms and expansive designer collections. Yesterday’s hippies have either grown up and grown out, or have been superseded by younger, hungrier replacements. The main difference in the items produced today with those from even a decade ago is in the quality.

Now any number of conglomerates design, manufacture and export any number of high-end furniture pieces, fabrics, lighting products, and accessories. When mixed with recycled panels in carved wood, old dyeing vats, birdcages transformed into sexy lights, masks and canvases, you have the perfect East meets West combo. It’s no wonder that many people specifically visit Bali with a view to furnishing their new apartment back home. Recent years have seen a proliferation of businesses that specifically source art, furniture, fabrics and artifacts on a buyer’s behalf.

One area that reflects this eclectic theatricality is to be found in some of south Bali’s newer commercial outlets—restaurants, cafés, clubs and hotels that are making design waves quite out of proportion to their size or standing. Take a look at the outstanding lighting design in Café Bali, for example, or the pared-down post-modernity at The Junction (see pages 207, 211 and 219). Potato Head Beach Club’s futuristic façade, composed of over 1,000 vintage wooden shutters salvaged from across the archipelago, is both a lesson in sustainable material re-use and a flight of architectural imagination (see pages 220–221). And for those who love to see reinterpretations of cultural concerns, but in a contemporary context, look no further than the funky W hotel, the latest outpost from this über-chic brand (pages 184, 202–205).

In our collection of houses, interiors are extremely varied. Because most are lived in by their owners, each sports an individual style that differs greatly one from the next. We have family homes with practical arrangements for teens, funky bedrooms for kids, family AV rooms for home entertainment. There are homes with private yoga rooms, attached offices, bars and studios. Some sport priceless art and artefacts, others are more down to earth.

Where they are unified, however, is in the care given to selection of furniture and furnishings, and in the quality. We’re seeing a lot less Asian style; Euro flair is on the rise. Along with Christian Laigre lookalikes—think sleek sofas with ottomans in cream and dark wood—there are iconic pieces from Italy and the Americas. These may be accented by some Asian decorative pieces, but that is what they are: accents.

One of the most notable changes is in the field of kitchen design. In the past, kitchens were tucked away in the back of the villa and equipment was rudimentary at best. Even high-end rental villas often didn’t have an oven, relying on a gas cylinder and hob for cooking. All that has changed with easy access to imported, high-end brands such as Bosch, Miele and Boretti, and the plethora of talented cabinet makers now resident on the island.

Detlev Hauth is one such artisan. After stints at Boffi, Poliform, Artemide and other big contemporary manufacturing companies, he moved to Bali nine years ago and set up a studio called Casa Moderno to manufacture products aimed at the German market. “Germany needs quality,” he notes, “and all my people here in Bali have the necessary skills.” Combining German technology with Italian sophistication, as well as Bali’s natural materials and craft skills, his kitchens are both sleek and functional (see pages 176–177).

Methods and technical know-how are European, materials and craftsmanship totally Balinese. For cabinets, he uses what he considers the best rail system in the world—a German one—to ensure that drawers and cupboards slide very smoothly and don’t slam shut, while other pieces are locally made but equally sleekly finished. “We also produce furniture for villas, shops and offices—all contemporary,” he says, adding that problems start once the style is set in the modernist idiom. “Clean lines need higher quality. If you produce a traditional Indonesian table or you build a traditional Balinese house you can hide all the mistakes; this is not so in contemporary—with contemporary, all is exposed.”

Detlav is but one of many such craftsmen based in Bali today. As competition grows, the demand for sophisticated products that really work, expands. Nobuyuki Narabayashi, or Nara-san, of Desain9 agrees. Having worked for many years at Japanese design supremo, Super Potato, he is now at the helm of an extremely individual design firm in Bali. As an interior designer of both commercial spaces (check out his refined craftsmanship at The Junction in Seminyak—page 219) and residential, he is well placed to comment on the scene in Bali.

Desain9 is, however, a little different to many of the design ateliers on the island, in that its specific aim is to use recycled materials as much as possible and transform them into new, timeless products. “As you know, Bali has an extremely particular culture and regional tradition,” explains Nara-san, “but that originality is disappearing because of today’s design homogeneity. My challenge is to re-compose true Balinese items, re-make the old culture, and transform it into new products.”

It’s certainly encouraging to see that companies like Desain9 have such an ethos and they stick with their ethics. They put their money where their mouth is, as it were. Their products and interior finishes look very slick and very contemporary—but at their heart lies a reinterpretation of Bali.

Indonesian architect Budi Pradono’s roof form at Villa Issi was purposely angled so as to obtain shifting patterns of light on the rigorous volcanic rock wall in the stairwell.

Another company that takes its sustainability credentials seriously is Ibuku, under the creative direction of Elora Hardy. Currently gaining publicity for its entirely built-in-bamboo Green Village residential project near Ubud, it uses several different species of bamboo to build in ways that are “in integrity with nature”. In the hands of Ibuku, bamboo is beginning to cast off its somewhat old-fashioned reputation, as designers manipulate bamboo’s versatility in furniture, flooring and wall materials.

“Quite often we cut splits of bamboo, then laminate them together under pressure,” explains Elora. “And if we want a graphic element, we slice duri bamboo lengthwise to reveal the nodes and internodes.” Then, instead of using the material to make an entire table or door, Ibuku may incorporate bamboo detailing within individual pieces. The end result is something sophisticated, something modern, yet something that retains a connection with Bali’s natural beauty. See the doors and kitchen counter on pages 84–85 for more of an idea of Elora’s work.

In contrast to Desain9 and Ibuku, some designers have begun experimenting with more industrial materials, moving away from Bali’s natural resources. As the island matures and expands, so does the availability of higher-tech methods and materials. Ateliers specializing in synthetic rattans, all-weather wicker, acrylic and polyurethane are proliferating. Heat and humidity, not to mention sea breezes and pollution, all take their toll, so many home owners are making more practical choices in their choice of décor items.

The wow factor in this 33-m swimming pool is a glass bottom in the shallow end. It allows for sneaky peeking from the games room below. Designed by KplusK Associates, the pool is surrounded by a number of discrete modern pavilions set aside, above and below.

Some of the quirky furniture pieces designed and manufactured by Valentina Audrito and Abhishake Kumbha at Word of Mouth combine such modern materials with witty, tongue-in-cheek expressions that are sold both overseas and on the island (see pages 212–215). Their inspiration comes from their lives, they say, but even though they’re Bali based, there’s not much in the way of tropicality in their work. Benches, chairs and loungers may be made in Bali, but they stand outside the vernacular in terms of style.

In addition to such locally made pieces with a European slant, home owners also have the choice of buying items made overseas. Each year, Mario Gierotto sources at the Salone Internazionale del Mobile in Milan to select items for his trendy home wares and furniture shop, simplekoncepstore: he believes that the increased population of expats has led to the demand for European pieces. In his own home (see pages 170–173) he mixes quality imports with some custom-crafted items and artworks that he has picked up locally. He is by no means alone in this.

Overall, as with the architecture, it is variety, quality and a certain individuality that we celebrate in this book. Most home owners have worked full-time on sourcing, designing, and incorporating their personalities into their homes—and because of the plethora of choices they now have on the island, they’ve been able to weave together highly covetable looks. We also invite you to look at some of the websites of designers, shops and manufacturers listed at the back of the book.

Conclusion

One thing that became very evident during that process of compiling this book is that Bali has a unique ability to keep re-inventing itself. Even though there is a more mercantile outlook nowadays, the island still retains its rich culture steeped in tradition and ritual, its welcoming people, and the beauty of its landscape. This is the Bali that attracted people in the first place. The fact that architects and designers, home owners and even the Balinese themselves are reinterpreting the island’s culture in a more international way doesn’t undermine the original essence of Bali.

We believe that the designs in this book are simply one facet, one “layer”, one stage of the journey in Bali’s development; in the future, different spaces, different interpretations, different structures will evolve. Perhaps that is why the island continues to beguile visitors and residents alike. It may not be Tropical Paradise any more, but it certainly isn’t Paradise Lost.

In one of the guest bedrooms at the home of architect Ross Peat is a self-portrait by well-known Melbourne artist Jody Candy.

Partial view of the core of the home, the central courtyard, looking towards the main living/dining pavilion. The grassy court is surrounded by semi-transparent, flat-roofed buildings and a variety of plants and trees. Because of the “see-through” nature of many of the pavilions, the property feels spacious yet there is still a certain intimacy about it.