Читать книгу Korea Style - Kim Unsoo - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

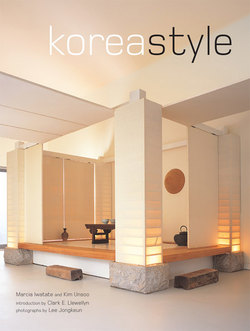

Оглавлениеkorean aesthetics, modern directions

CLARK E. LLEWELLYN

KOREA STYLE is epitomized by the beauty and humility observed in the offering of a cup of tea with two hands gently folded while lightly grasping the base of a perfectly proportioned white porcelain cup. The guest, in turn, receives the object of tradition and art with two folded hands and a slight nod of the head in appreciation of the respect shown. Korean architecture, interiors, art, and artifacts generate similar signs of appreciation and reverence for their natural world. Coupled with this is the Koreans’ innate sense of beauty, which extends from the smallest object to the largest and allows them to create not only structures, interiors, and artifacts that are quintessentially Korean but also assimilate those of others so that they attain a Korean character. Such is the essence of “Korea style.”

As a Westerner first visiting Korea, I misunderstood an architect when he pointed out the natural placement of a stone in front of a residence and said how beautiful it was because it was an old stone. Unwittingly, I asked how old he thought it was in geological time. He did not reply. To understand his meaning and desire to have an old stone, it is necessary to learn something of the teachings of a seonbi, a Korean philosopher from the Yi Dynasty (AD 1392–1910), better known today as the Joseon Dynasty, who taught that an old stone or rock represents age, not literal age, but a respect for age – respect for parents, teachers, and elders. The old rock has weathered many storms, seen the heat of summer, the bitter cold of winter. It is creased by water and smoothed by wind. It is not polished. It is not unrivalled by Western (or even Chinese and Japanese) standards, but viewed through Korean eyes it is perfect because of its reflection of age, nature, and sense of place.

Since antiquity Koreans have developed this special affinity with nature, an affinity which expresses itself in unmistakably Korean images of pastoral villages tucked between rocky mountains, forests of gnarled pine trees, lush green rice paddies, and walls and paths built with stones in their natural forms. Mountains form a pocket on the north and the Han River forms a soft, flowing line on the south of the 600-year-old capital city of Seoul. Early Neolithic remains found among the dolmens were placed in harmony with the natural landscape. During the Ancient Period (AD 200–600), houses evolved from pit dwellings to structures with earthen walls and thatched roofs, then to log structures, and finally to structures which showed the first evidence of the unique Korean raised floor panel heating system called ondol. It is believed that this heating system, which was to become so widespread in the seventeenth century, was never implemented in China because tables and chairs were used instead, and although floor seating did travel to Japan from Korea, the Japanese did not employ under-floor heating either. This technological innovation is still embraced by contemporary residential architecture for its energy efficiency, even distribution of heat, and elimination of the need for diffusers, radiators, and other visible mechanical devices. Under-floor radiant heating has since spread widely in the West and Japan.

The Three Kingdoms of the Ancient Period were brought together under the United Silla (seventh to tenth centuries), which absorbed the mature culture of the Tang Dynasty in China while developing a unique cultural identity. Buddhism and its art and architecture flourished during this period. In AD 918, the last king of Silla offered his kingdom to the ruler of Goguryeo, which took the name of Goryeo (“Korea” to Westerners). The Goryeo Dynasty (AD 918–1392) brought about a state embracing both Buddhism and Confucianism, and developed the ancient capital city of Songdo (now Gaeseong) in North Korea. The non-axial arrangement of the city responded to the natural contours of the mountainous landscape and led to the proclamation that nature should prevail over human design. Geomancy, a method of divination for locating favorable sites for cities, residences, and other activities, was proclaimed as a leading principle of design. The basic theory stems from the belief that the earth is the producer of all things and the energy of the earth in each site exercises a decisive influence over those who utilize the land. It is believed that when heaven and earth are in harmony, the inner forces will spring forth and the outer energies will grow, thereby producing wind and water; interestingly, the Korean word for geomancy, pungsu, literally means “wind and water.” Principles of geomancy have been used to great effect in the orientation and design of Bedrock Manor (page 166) by Kim Kai Chun, and with the use of water elements, a leitmotif common to many of the residences in this book, notably those designed by Cho Byoungsoo, Choi Du Nam, and Kim Choon.

Guests to Fashion Designer’s Muse (page 50) enjoy lounging around the massive rough-edged granite slab table in the double-height living room, seated on floor cushions with accompanying cubicle armrests.

All windows capture the sensuous outlines of the deep eaves, which, combined with the interplay of columns and beams inside, heighten the sensation of being inside a traditional Korean house (hanok) in Reincarnation of a Bygone Era (page 190).

The basis of the architecture and art that we see today, and which forms much of contemporary “Korea style,” was established during the Yi (Joseon) Dynasty, which supported the ideals and practices of Neo-Confucianism. The principles strongly influencing design at this time included dedication to simplicity, moderation, respect, and restraint. Seonbi also communicated the importance of writing, painting, meditation, and a minimalist approach to life which valued deep respect for all things natural. Pottery was simple yet exquisitely proportioned. Colors and decoration were minimized in both art and architecture, thus exposing the simplicity and purity of the materials. Simplistic perfection of man was sought as a counterpoint to the perfection of nature’s complexities to achieve simplicity. In its ideal state, “Korea style” values not only age and nature but also a commitment to minimalism as a way of life. These principles are employed to perfection in many of the design elements featured in this book, notably in the buildings designed by Cho Byoungsoo, Kim Incheurl, and Seung H-Sang.

Confucianism engendered a deep respect for all things natural, in particular for what their natural state might have been like without the intervention of man. This natural state found beauty in stones left unpolished, wood left unfinished, landscapes left untouched, and plants growing without stylistic shaping. The Korean culture discovered aesthetic and moral value within materials exposed to and thus altered by the natural elements. The sun bleaches and dries wood, the wind reshapes and textures both wood and stone, rain flows across surfaces gradually etching its path into the materials. Heat and cold expand and contract materials, reinforcing the aging process. All of these effects are evident in the highly esteemed vernacular complex, Masterpiece of Confucian Architecture (page 204).

The Korean concept of space has also been influential in its architecture and interior design. Historically, the spatial perception of Koreans differs dramatically from that of Westerners. When early Westerners first viewed traditional Korean landscape paintings and drawings, they found them flat and lacking in depth, shading, and realism. The Koreans, on the other hand, were astonished that Western landscapes looked so realistic, like mirror images, and were devoid of expressive brushwork and imagination. Unlike in the West, the function of traditional landscape painting in Korea was to act as a substitute for nature, allowing the viewer to wander imaginatively. The painting was meant to surround the viewer and provide no “viewing point” or pure perspective. This same principle can be observed in landscapes, courtyards, and other outdoor spaces surrounding buildings throughout Korea, and partly explains the importance to the Koreans of having a view, especially one facing a mountain. Likewise, while the Japanese developed Zen gardens with purity and symbolism, the Korean culture continued to embrace natural expressions and the outdoors with much less formality. Trees, grass, and natural gardens are preferred to manicured and artificially developed landscapes. Grass, which has been browned by winter and the lack of water is considered more natural, and thus more beautiful, than the arranged perfection of raked sand. Trees, which reflect the effects of weather and time, are held to be more beautiful than a “tortured” bonsai.

Connections between nature and the indoors are important within most Asian cultures. Providing this connection, courtyards were developed as an essential design element throughout much of Asian architecture. While courtyards generally serve the same purpose all over Asia as a means of unifying the exterior and interior, they are culturally and architecturally treated quite differently. Traditional Japanese architecture employed engawa as a modulation space between the outside and inside, while Korean houses opened directly to the outdoors through a space called daecheong, where all doors were removed and hung under the eaves in the summer, as shown in Hanok Case Study (page 138) and Masterpiece of Confucian Architecture (page 204). Daecheong also served as multifunctional spaces that could be used for various domestic functions as well as a free-flowing space leading to the private rooms on its two sides. Metropolitan Sanctuary (page 18) and Maestro’s Utopian Vision (page 174) incorporate both the open and free-flowing features of daecheong.

Korea faced difficult times during the global surge towards “modernism.” Japanese occupation, the Korean War, and other geopolitical issues retarded the implementation of modernization in Korea. After the Korean War, Korean architecture and design languished for many years without strong leadership or definition. It was not until the principles of the modern movement were combined with the principles of Korean vernacular architecture that the content began to emerge as a distinctly Korean “style.” Two of the most influential architects, Kim Joong-up and Kim Swoo-geun, emerged in the 1960s upon their return to Korea from studies abroad, at a time when economic progress was propelling a construction boom. In addition to introducing the International Style to Korea, they brought a sense of “architectural nationalism” to their designs because of their native Korean heritage. While the Western world looked to Leonardo Da Vinci in the sixteenth century and Le Corbusier in the twentieth century for proportional systems to create a more humane dimensioning system, Korean architects and designers turned to the ancient flexible module of kan and the measurements of cheok. The “organic” qualities of Korean modernism were probably first embraced by Kim Swoo-geun, as evident in Maestro’s Utopian Vision (page 174) and Tribute to Korean Modernism (page 182), and remain as central design concepts for many of the architects/designers featured in this book.

Massive wooden columns placed in a zigzag pattern provide the sole support for the concrete slab roof in Square within a Square (page 212), harmonizing with the interior’s natural materials and exposed concrete.

Elegantly curved pitched black giwa tiled roofs, dormers, and deep eaves are typical of traditional upper-class Korean houses, as exemplified in Hanok Case Study (page 138).

As peace endured, Korea developed rapidly into an industrial base within the Pacific Rim and began to actively participate in the global economy. Beginning in the 1970s, a strong migration of many young, bright, and talented architecture and design students from Korea began traveling internationally to attend the world’s most reputable graduate programs. At the same time, some prestigious programs within Korea began developing outstanding schools, which were strongly influenced internationally. Much of the international influence came from Korean faculty who attended graduate programs abroad and returned to practice and/or teach. These people are much more able to understand and express both theoretically and as built work contemporary architectural expressions which are informed and influenced by their traditions. This is especially true of the Yi (Joseon) Dynasty influence – integration of the arts and how houses become “galleries” for the display of cultural artifacts. Classic Korean objects, be they ceramic kimchi pots, soban tray tables, dwiju grain chests, or hanbok costumes – items that immediately distinguish themselves as being uniquely Korean – are used with vernacular panache in interior decoration. Old rice cake boards are used as coffee tables, antique grain chests double up as storage for books and other household items, cushions are upholstered in Korean moshi linen and jewel-toned silks, and old stone mills and “ironing blocks” are used as garden “stepping stones.” Similarly, stone figures once reserved for temples and royal burial mounds are displayed as modern-day objets d’art. “Korea style” is thus inextricably linked with art, craft, and architecture as showcased in Metropolitan Sanctuary (page 18), Lock Museum and Residence (page 28), Fashion Designer’s Muse (page 50), Mountain Atelier (page 86), Folding Screen Mountain Retreat (page 116), Living with Art (page 128), and Collector’s Hillside Haven (page 152).

Simplicity, moderation, constraint, and a deep respect for all things natural have remained the hallmarks of Korean architecture and interiors throughout the ages. Yet, despite maintaining these traditions, contemporary Korea is unique in its acceptance of contrast and lack of formality as part of its expression. Old is intertwined with new, rural with urban, unstructured with structured, noise with silence, and light with dark. “Korea style” often employs many of these contrasting elements to create uniquely harmonious relationships. Hanok Case Study (page 138) and Reincarnation of a Bygone Era (page 190) are classic examples of how old can be intertwined with new, while Kim Choon, Kim Kai Chun, and Seung H-Sang have a talent for contemporizing traditional tearooms. Portions of an old wall built in the Yi (Joseon) Dynasty for protection and definition around the city of Seoul emerge from the city perimeter at irregular intervals and provide for interesting relationships between old and new, as evidenced in Historical Stone Wall House (page 40) by Choi Du Nam. Square within a Square (page 212) shows the contrast between rural settings and urban designs, Mountain Atelier (page 86) exemplifies how unstructured elements can be combined with structured ones, and Reflex Penthouse (page 146) demonstrates the contrast between noise and silence in a single space. Light and dark have once again been reintroduced into contemporary structures creating an ambience of mystery, subtlety, and reflection. Walls have transparency, translucency, and texture. Spaces have shade, shadow, filtered light, and moonlight. Papered screens, large overhangs, and movable walls all are historical precedents which contribute to contemporary expression. The Lock Museum and Residence (page 28), Fashion Designer’s Muse (page 50), Folding Screen Mountain Retreat (page 116), and Tribute to Korean Modernism (page 182) all maximize the use of papered screens and filtered light. To the unobservant eye, these contrasts may appear strange and discordant, but within imperfection rests the perfection of nature.

As the world becomes more globalized, most countries are losing their architectural and cultural heritage to technology and expanded economies. National expressions of “style” and “substance” take a back seat to nondescript buildings and interiors which respond only to changing populations, limited budgets, and functionality. Some respond to this loss through mimicking or applying traditional images to pedestrian structures. The compromise reached often results in poor architecture and internal design that is neither contemporary nor traditional. Korea, however, has made significant gains in meeting the challenge of integrating tradition with contemporary architecture and interiors. Reaching a point where it can be identified as “Korea style” is significant. Through Korea’s effort, other cultures may learn how to develop a style which reflects their own culture while meeting the demands of modernization. Korea’s inclusive approach to design, integration of nature, and respect for heritage are important fundamentals for success. As this book shows, “style” is not necessarily shallow nor applied. It can mean substance, integration, and promise.

The Reflex Penthouse (page 146), a study in oblique angles and minimalist aesthetics, was an ingenious response to the site’s physical and legal restrictions.