Читать книгу Korea Style - Kim Unsoo - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

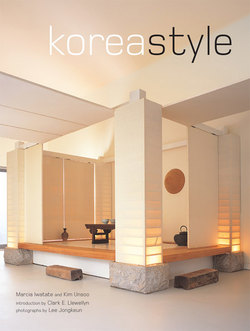

Оглавлениеmetropolitan sanctuary

DESIGNER KIM CHOON

This 210-square meter split-level house in Pyeongchangdong, a residential district coveted for its proximity to downtown Seoul and to the natural wonders of Bukhan Mountain, is home to interior designer Kim Choon and his wife, a creative director, and their dog.

One goal in building the white stucco and Indian sandstone-clad residence in Pyeongchang-dong was to live in unison with the strong gi or primal force of the universe that this area is said to possess. The concept comes from the Five Elements School and Yin and Yang, which still play an important role in the lives of Koreans (see page 38). By recessing the house into the steeply sloping site, the designer has obtained harmony with the surrounding landscape, with the added benefit of privacy from neighbors. He also strongly believes that sub-ground structures are energy efficient as they are well insulated against the elements, subject of course to moisture-guard provided by double retaining walls. “I wanted a sanctuary to stimulate the five senses: music provided by the birds, open spaces with natural light, aromas from my wife’s cooking, views of lush greenery, and a simple, easy-maintenance environment.” The addition of an interior pool, one of the designer’s signature features, also feeds the five senses.

Reminiscent of Korean vernacular architecture, the house is surrounded by courtyards. Three recessed courtyards, planted with maple trees, wisteria, and carpets of moss to ensure seasonal views, provide access at various levels as well as screening for each room. The house merges seamlessly with the courtyards because of the expansive use of glass. To withstand severe winter cold and condensation from the floor-heated interior, a double-glazed German window system was favored over frameless glass. The U-shaped spatial arrangement and the use of folding doors for individual rooms are reminiscent of the interrelated linear layout of traditional architecture. The dining room, with rooms built on either side, resembles the multipurpose space between the front and rear courtyards, called daecheong, in traditional Korean houses (see page 138). The individual rooms are enclosed yet airy since all doors and windows are left open much of the time to heighten the connection with the exterior.

While the courtyards are contained and intimate, the interior is spacious and bright. Exposed concrete floors, glass walls, blond wood, and pure white walls contribute to the home’s contemporary minimalist ambience. At the same time, they reflect a traditional aestheticism that values minimalist shapes, overall effect, and balance over excessive attention to detail. The couple’s enthusiasm for antiques, collectibles, and art knows no bounds, making this unassuming space an ideal setting in which to display their fascinating collections.

The living room glows in the late afternoon sun, softly filtered by a large maple tree planted in the upper courtyard. Clustered around a striking coffee table constructed from pieces of old pinewood rice cake boards, the crisply tailored canvas seating is offset by tasteful Korean antiques: soban tray tables (see page 157, below) and a rare zelkova wood steamer trunk. The trunk appears Western but is unmistakably Korean because of its lock design. The wooden figurines on top were discovered in a flea market in Beijing. A large sisal carpet defines the seating area. The massive fireplace with white marble surrounds, where three separate fires can be burned, dominates the entire south wall. In the central fireplace section, dragon andirons purchased for feng shui protection are, oddly, of French origin. The audio-visual system’s towering B&W speakers are disguised behind screens high on the walls, while AR speakers rest in an opposite corner and on the roof of the teahouse. The blank wall above the fireplace functions as a projector screen. Spanning the entire length of the wall on the upper courtyard side, sturdy steel bookshelves support the couple’s extensive collection of books and magazines. The catwalk above the shelves provides additional space for displaying a tall Thai Buddha and a Chinese birdcage collection, while also allowing for window maintenance.

Sandwiched between two courtyards, the focal point of the dining room is a narrow pool surfaced with black granite and lined with old millstones and blocks once used to “iron” laundry with wooden bats (see page 46). Crafted by the late Japanese friend and furniture maker Kimura Jiro, the customized dining table, paired with vintage bentwood chairs, is made of reclaimed zelkova wood hand rubbed with natural lacquer. A Jasper Johns “Crosshatch” silkscreen print and a Thai Buddha image are displayed next to a pair of striking French iron doors discovered in a New York architectural salvage shop. The table is set with hand-thrown porcelain inspired by the pure color and forms of the early Joseon period. Marei, a Tokyo-based design and restaurant consultant studio co-owned by the wife and a partner designer, created these for a restaurant project in Seoul.

The culinary-loving wife designed the functional details of the open-plan kitchen, which is finished in a palette of white – honed white marble countertop and white laminate cabinetry – with a rear back-up area. The stainless steel gas cooker top, oven, and dishwasher are from Neff, a German manufacturer. Conveniently at hand, dried foods and seasonings in glass jars make an interesting and colorful display on inset shelves. An opening in the back wall provides easy access to the kitchen counter from the rear back-up area. Designed to cover the entire kitchen area, the large hood efficiently absorbs all cooking fumes. Beam lamps above the grilles project fingertip lighting. The doorway at back leads to the walk-in closet located between the master bedroom and bathroom.

An antique stone frog, the shimmering flames of floating candles, and the soothing sounds of trickling water greet guests as they enter the dining room. Set with black pebbles, old millstones, and blocks once used to “iron” laundry with wooden bats, the pool, along with the moss-covered garden and kilim carpet, add textural interest to the exposed concrete dining room floor.

A collection of Baekje (18 BC – AD 600) and Unified Silla period (AD 668–935) earthenware is displayed under a large “Hollywood” acrylic on canvas by Kim Janghee. The pure shapes and combed patterns of the ancient Korean earthenware harmonize beautifully with the contemporary painting.

In order to keep the kitchen compact and tidy, the owner’s extensive collection of tableware and bulky kitchen appliances, including a professional grade slicing machine and ice cream maker plugged in and ready to go, are stored in the rear pine-veneered floor-to-ceiling closet. Electric outlets have been provided in two different voltages, Korean and Japanese, because of the many Japanese-manufactured appliances in the kitchen.

Installed on the opposite side of the spacious six-meter-high living room, the teahouse, another signature feature of the designer, provides an intimate and meditative space. Although the design incorporates contemporary strip lighting and other innovative features, and is without doors, it does contain vernacular elements such as papered walls, an oiled-paper ondol floor, pinewood borders, and round pillars (traditionally forbidden in private residences but often seen gracing old upper-class houses). A novel element is the tabletop floating above a sunken pit – inspired by those found in contemporary Japanese restaurants – to provide greater comfort to users than conventional floor seating with tray tables. The tabletop and its base block can be removed, and a hinged panel, set upright into the back wall, can be lowered flush to the floor. This versatile panel, oil-papered on the reverse to match the floor, allows traditional bedding stored in the closet paneled with old carved wooden doors on the right, to be laid on the floor. By lowering the woven bamboo screens, the teahouse becomes an extra guest room.

Inspired by traditional Japanese aesthetics, the modern woven bamboo floor lamps are designed by Marei and made by a group of skilled Japanese artisans. The lamps replicate the linear shape of the adjacent antique dwiju grain chest, stripped to expose its natural blond color. Dwiju were constructed with four sturdy posts to support the weight of the contents. Straight-grained wood was used for the posts while panels of beautifully grained woods, such as the zelkova seen here, were employed for the front. A collection of late Goryeo Dynasty (AD 918–1392) celadon liquor bottles is displayed on top.

An antique soban tray table embraces two old lacquered paper craft containers used for holding a literati-scholar’s accouterments. Such containers were crafted in sets ranging from one to six. The starkness of the white canvas-upholstered armchairs is counterbalanced by eye-catching cushions covered in the famed Charles and Ray Eames “Small Dot Pattern.”

With their ovoid bodies and graceful necks, the celadon liquor bottles on top of the dwiju grain chest on page 24 are in the classic shapes of cheongja. Although influenced by Chinese wares such as Ru, Ding, and Yue, the gray-green hue – coveted by the aristocracy and Seon (Zen) Buddhist monks who preferred it to white porcelain – and sanggam inlay are unique to the Korean peninsula.

Framed by a roaring fire, a collection of burial horse clay figurines from an unknown period is a whimsical adornment on the pinewood slab coffee table set with champagne and finger food.

In a corner of the living room, a refined late Joseon-period ginko wood soban table holding a stack of antique dishes and art books, is paired with a large canvas floor cushion on a kilim carpet.

The linen closet in the bathroom, carved with flowing calligraphic works by the owner’s father, is a reproduction of a traditional bookshelf-cum-cupboard. It is a good example of Korean furniture that is highly esteemed by local and international collectors for its simplicity of lines and planes, discreet use of metal hardware, and pragmatic design. Hinged doors not only pull open but also slide in either direction, allowing access to every corner of the cupboard. An early “Building” collage by Ohtake Shinro adorns the wall. Throughout the house, a personal, eclectic mix of objects throws period and contemporary pieces together, such as the stainless steel Alessi canisters, Chinese lacquered letterboxes, and Korean celadon ware seen on the hewn pinewood vanity counter. Unusually, everyday table wine is housed below.

The powder room is an ever-changing gallery for the couple’s extensive collection of miniatures, such as the old Moroccan kohl containers shown here. An old pinewood rice cake board is fitted with a stainless steel basin and fixtures from Vola.

A nineteenth-century zelkova wood yakjang – a medicine chest with a distinctive row of small drawers originally used to store medicinal herbs, and now toiletries – stands in front of a window looking out to a moss garden. A wood Thai Buddha on top is silhouetted against the light. An extraordinary life-sized reproduction of one of the famed Chinese Xian tomb terracotta soldiers and a light-installed Balinese offering house in the background are glimpsed through the window.