Читать книгу Korea Style - Kim Unsoo - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеlock museum and residence

ARCHITECT SEUNG H-SANG

Daehakno, meaning “University Road,” is an area in Seoul known for its art and youth culture. Often compared to Montmartre in Paris, it was originally the home of Seoul National University, Korea’s most prestigious institution of higher learning. The expanding university has since moved to another location, but the street remains a popular hang-out for people from all walks of life. Many of the old residences have also disappeared due to the rapid commercialization of the area. Now, over forty theaters and concert halls, along with cafés and restaurants serving everything from authentic Korean barbecue to fast food, occupy the area.

The building, constructed without the use of a single bolt, resembles a large rust-red box encased on all sides in uninterrupted sheets of Corten steel. To avoid leaving traces of welding on its surface, an innovative technique of welding the steel on the inner side was employed. A single box window punctuates the monochromatic façade. Perched on top of the monumental steel box is the glass box housing the living quarters. The building plan and its model was the first architectural work to be included in the collection of the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Korea.

Amidst this disjunctive urban landscape of old and new, Choi Hong-kyu chose to build a spectacular home for his family and beloved collection of over 3000 locks from Korea and abroad. Hailed as a modern-day blacksmith and the owner of a wildly successful architectural hardware store called Choigacheolmuljeom, Choi is an avid collector of Korean antiques and an expert on metalwork. He has single-handedly changed the perception of metal and metal-workers in Korea today. Committed to providing a huge selection of architectural hardware, he opened his shop in 1989 with five designers on the staff and a workshop where skilled blacksmiths turn out regular products as well as custom-designed pieces. He also runs a blacksmith school with the hope of reviving the art and craft of traditional metalwork.

A multifunctional building was required to house both the public (commercial and non-profit) and private spaces: a café on the ground floor, an antique shop and gallery on the second floor, the museum’s temporary exhibition room on the third, a permanent collection on the fourth, and a residence on the fifth and sixth floors. “Most people regard metal as being cold and hard, but to me it is a warm and soft material with infinite potential to variegate. I wanted the building to express these qualities of metal.” Deeply impressed by architect Seung H-Sang’s work, especially his design for the headquarters of advertising company Welcomm, Choi commissioned him to design the Lock Museum Building with a vast floor area of 1600 square meters. The architect’s philosophy is to allow the innate qualities of materials to express themselves. His signature material, untreated Corten steel, was employed for this project without the addition of other textures or finishes.

Duality similar to the hard/soft, cold/warm characteristics of metal is manifest in the inner design of the Corten steel enclosure: the paper-swathed glass box residence perched atop and the glass atrium inserted into its central core opening inner spaces to the sky. The architect refers to the atrium, which dissects the upper three floors of the building, as also being a device to orientate visitors within the dark museum. The unadorned architectural material defines the character of the building, allowing time and the elements to produce a protective patina of rust. In this building, the passage of time not only enhances the beauty of metal but also magnifies the historical value of the precious artifacts housed within.

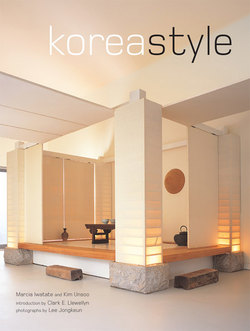

Sliding papered latticed screens envelop the glass-walled residence and imbue the house with softly filtered light and a tranquil ambience. At night, the screens are fully opened to reveal the glittering city nightscape. The diagonal lines of the staircase leading to the upper mezzanine level add to the dynamic aesthetics of the house.

The staircase railing extends around the mezzanine floor for visual continuity. Lined with built-in bookcases, the passageway leads to the master bedroom suite. A glass-enclosed courtyard provides plenty of sunlight and views from the family room, hallway, and master bedroom of a lush grove of black bamboo.

The top half of the central glass atrium is seen from the bridgeway located on the west side of the residence. A Corten steel planter is built along the outside of the inner corridor. The void below houses the moss-covered garden in the fourth-floor museum.

The pristine double-height living room features an entire wall of papered latticed screens. Designed by the owner, the mini-malist coffee table adorned with a bowl of fragrant quinces was crafted in sandblasted stainless steel at his workshop. His portrait sits on the low pinewood bench at the far end of the room.

Highlighted by filtered light, the grid pattern of the screens and linear planes of the pinewood dining table and Corian kitchen counter create a stunning composition. The kitchen counter and cabinetry are all from the Spanish manufacturer Gamadecor.

Enamored by its wonderful aromatic and therapeutic qualities, the owner imported a hinoki (cedar) wood tub from Japan for the master bathroom. The hinoki bathroom is located off a long galley sink area, with a Corian counter and cabinets designed by the architect, which connects the master bedroom at one end and closet/storage spaces at the other.

Built along the north side of the living and dining area, the terrace fulfills the owner’s dream of a roof garden and water feature. A careful selection of Korean wildflowers and plants border the stone path. A white plastered “flower wall,” typical of those developed in the sixteenth century to decorate the inside of stone boundary walls, contains delicate hand-molded and fired plum blossoms by artisan Suh Sanghwa, who restored the walls of Gyeongbokgung Palace.

Box-framed antique pillow ends make beautiful displays on a shelf in the family room.

A contemporary clay pot by ceramic artist Lee Heonjeong, placed in one corner, softens the linearity of the living room.

A 150-year-old rice cake board serves as a coffee table in the upstairs family room. Carved out of a single piece of pinewood, its concave center and short legs are characteristic of those found in the Tongyoung region of Korea.

A pair of lava stone tomb guardians from Jeju Island greets visitors as they enter the museum. The moss-covered garden on which they are placed is located at the bottom level of the atrium that dissects the upper three floors of the building.

Korean fish-shaped locks are generally in the shape of a Crucian carp. They symbolize success because of the expression “the fish turns into a dragon,” fertility as fish produce many eggs, and protection as fish do not close their eyes even at night. The color blue refers to spring and is believed to ward off evil and bring prosperity.

Traditional Korean house gates opened inwards with a ring on the outside and a latch on the inside. Latches were often more symbolic than secure. This late Joseon-period gate latch is very realistic, with the growth rings of the wood used to depict the backs of the fish.

A streak of sunlight streams in from the small gallery in the back installed with windows.

Typical of all Korean locks, regardless of the period, a hambak lock features a round watermelon-like attachment in the center of a basic deegut (third letter of the Korean alphabet) shape. Made in the late Joseon period, it has a locking mechanism that is somewhat similar to modern-day locks.

The museum is designed as a labyrinth for visitors to “discover” treasures in the dark. Locks are encased in glass, like pieces of precious jewelry, dramatically highlighted with concentrated beams of narrow light. Lighting at the Gallery of Horyuji Treasures in Tokyo, designed by MOMA architect Taniguchi Yoshio, was a great source of inspiration for the owner when setting up this museum.

Curated and designed by the owner is an exhibition entitled “Locks of the World.” The plastered panels on which the locks are mounted were painted in the five traditional colors of Korea. Called obang saek, the colors – blue, red, yellow, white, and black – symbolize the Five Elements as manifestations of Yin and Yang on earth (wood, fire, earth, metal, and water) necessary for balance and harmony. To have one element out of balance weakens both the mind and the body, and disrupts the flow of gi or primal force of the universe.

At the owner’s suggestion, glass walls were used in the museum’s temporary exhibition hall to showcase his collection of prehistoric Baekje (18 BC – AD 600) and Silla (57 BC – AD 936) earthenware and stoneware. Floor-to-ceiling sliding panels are pulled closed when wall space is required inside the exhibition hall.

A selection of typical Korean hambak locks.