Читать книгу The Landlord - Kristin Hunter - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

Lankily Lincolnesque, faintly skeptical, Borden spoke with pencil poised.

“And in just what ways does this Negress remind you of your mother, Elgar?”

Even a crease in his goddamned pajama trousers. Over them a natty plaid flannel dressing gown. Though the consulting room was as seedy as ever, and floured with circa-1890 dust. On Elgar’s fees, couldn’t he at least afford a cleaning woman once a week?

“Every way,” Elgar replied. “Very massive. Very dominating. Very dangerous.”

“Yes, and very black, if I recall your description. Your mother is a large woman, yes? But she is also white, no?”

That comma yes, comma no at the end of key sentences. Suggestion of Vienna. When it was palpably clear Borden had never studied under Old Papa Whiskers in Vienna. If, indeed, under any of his disciples anywhere.

“Hey, Borden, how come I never see any of your diplomas hanging around here? Could it be you don’t have any?”

“I see I am arousing your hostility, Elgar,” Borden said, tossing a dark, damp, Gregory Peck lock back from his forehead. He did not quite make it. It hung there limply, like the little girl’s who was sometimes horrid.

“—Else why at this particular moment in our relationship would you be questioning my professional credentials?”

“Had to come up sometime,” Elgar answered. “For twenty-five bucks a session, I don’t want to be taken apart by an amateur. Destruction at the hands of a professional, or nothing. It’s my right. I demand it.”

A note of personal indignation crept into Borden’s voice, then was put down by his relentless control.

“And how many of these so-called professionals do you think would make themselves available to you at this hour? No, Elgar, they keep office hours. In nice, air-conditioned, downtown offices. Not in festering rat-holes in the Trejour Apartments, convenient to patients and to nothing else.”

Elgar felt remorse. With weak, watery eyes, long, knobby limbs, and catarrh due to chronic sinusitis, Borden was a poor second to Gregory Peck. A poor second to everybody, really, including plump, professional shnooks in plushy downtown offices. And, sniffling over there behind the owl-rimmed specs, he did look a bit rumpled and sleepy.

“Your questions are of course legitimate. I will answer them at another time. But why do you question my background and my competence now? Why now, Elgar?”

The bastard’s instincts were sharp as a coonhound’s, even when he was full of sleep. Elgar, blank, felt his teeth clamp together. Blocking. Stubborn.

“I will tell you. You are trying to involve me in an argument, a sideline. Because you do not want to hear that this woman who upset you today is not the same person as your mother.”

Elgar banged his fist into Borden’s cruddy old black leather couch, raising a puff of elderly dust. Real doctors had Danish modern, imported, the best, didn’t need ratty antiques as symbols. But real doctors had office hours and professional patience strictly limited to fifty minutes an hour. Elgar needed a lifetime of patience. His fist went through the cracked headrest, landed in a nightmare of sleazy sawdust.

“It’s hopeless, Borden!” he screamed. “Every time I try to do something, it involves people! And people are all impossible!”

“You mean,” Borden said, “they have motives and wishes of their own. They will not gratify your every need instantly, the way your parents did when you were a baby.”

“Like hell they did,” Elgar said. “Like hell. They did no such thing.”

“Of course not, or you would not be here with me tonight,” Borden answered smoothly. “But you wished they would. And you still wish it. A happy babyhood. It is the point in life at which you are arrested, Elgar.”

“I tell you,” Elgar howled, “it’s not just me, Borden! People are all sick out there! It’s a jungle.”

“Nevertheless, everyone out there is not your mother or your father, Elgar. And most of them are probably not as sick as you.”

The growl began deep in Elgar’s throat. “Ohhh, you imitation Viennese quack,” he raged. “Ohhh, you sniffling Hollywood understudy, will you never listen to me? I tell you, today I was chased by raving Indians with tomahawks and frothing Amazons with revolvers. And they weren’t even real Indians and Amazons, they were crazy phonies! Now how can you sit there like a badly designed effigy of Lincoln and tell me that is normal?”

“It is certainly,” Borden admitted, “very odd behavior. At least by our standards.”

“By any standards in any sane world, Borden! But the world is crazy, that’s what it is. Crazy full of maniacs!”

He sat up on the edge of the couch and leaned forward, palms up, straining to communicate.

“Borden, this morning I was so happy. The sun was shining, I had a purpose, I loved everybody.”

“You did not,” Borden interrupted. “You have never loved anybody, Elgar. Not even yourself.”

Elgar decided not to get caught on the horns of that old dilemma. He let it pass.

“Well, I had that good feeling. You know. The Best of Show feeling.”

Borden nodded. Taking Best of Show with his champion Great Dane had been the brightest event of Elgar’s childhood. Though even on that day of shining accomplishment the only identification under his picture in the papers had been “Owner.”

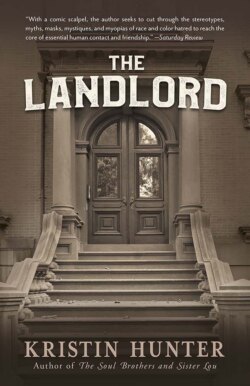

“I was actually singing. Out loud. I was going to do useful work in the world. Keep busy. Be a landlord.”

Elgar felt his face screw up grotesquely and grow inflamed. Thank God he was no longer ashamed to cry in front of Borden.

“Now I see there’s nothing for me to do but join a Trappist monastery! And even there I’d have to get along with the other crazy monks.”

“You would, Elgar,” Borden agreed sadly.

“So what’s the use, Borden?” Elgar wailed, tears gushing down his twisting face.

“The use of what, Elgar?”

“The use of all this talking and analyzing. What’s the use of getting well if I have to live in a sick world?”

“Maybe then it will not seem so sick to you.”

“Oh no?” Elgar retorted. “You mean, when we’re finished, imitation Indians out to scalp me in broad daylight will seem perfectly normal? In that case, Borden, I’m quitting right now.”

“Your privilege,” Borden said. “If you are not interested in being happier and functioning more effectively.”

“You don’t hear me, Borden!” Elgar screamed. “Man, you don’t hear, see, or read me at all. Oh, you are so dumb, Borden. Dumb, deaf, and blind.” He pounded the couch for three-time emphasis. “Why should I be interested in functioning? How in hell can I be happy? If everybody else is crazy?”

“Perhaps you can help them to be less so,” Borden said.

“Help those crazy, man-eating cannibals? Why should I? So they can eat me alive? Get away from me with that sick, social-worker jazz, Borden. All I want is to enjoy my life. Fast cars and sweet music and fast, sweet women. I can afford them. Why can’t I enjoy them?”

“Yes, why can’t you?” Borden’s mocking flute note echoed.

“That’s all I want,” Elgar said defiantly. “Is it so much to ask? Why the hell do you want to complicate things by having me help people, for God’s sake?”

“Elgar,” Borden said, “perhaps you imagine I put up with crazy, man-eating cannibals like you for the money and the things it buys. But I assure you, no amount of money could pay me to be eaten alive like this.”

Elgar sank back on the uncomfortable couch. “You great, big, sentimental fraud. If I ever find out you’ve been lying to me I’ll murder you, you hear? And then I’ll go out and commit atrocities on sweet old ladies.” His gusty sigh was followed by a sour belch. “What’s the first step, Borden?”

“First,” Borden said, “we learn to distinguish between this very interesting and unusual Negress and your mother. So you can deal with each in appropriate fashion. Your mother is white, yes?”

“Borden, as I have said many times before, you are a genius of the obvious. Of course my mother is white, you dimwit! But take a picture of her and print up the negative, and you’ve got Madam Margarita.”

“Madam Margarita?”

“Alias Marge Perkins. Second floor rear. Fifty dollars a month, which I have not been paid.”

Borden raised a long, knobby, significant finger. “Just a thought, Elgar. Does the second floor rear have any special associations for you? A particular part of the house in which you grew up, perhaps?”

“It was the bathroom,” Elgar said. “Oh, Christ, Borden, you’re way off base. And we’ve been at it two hours.”

“I am not at my best under such conditions, Elgar,” Borden admitted stiffly. “Especially when my sleep has been interrupted. I too am human.”

“Well, rest up then, baby,” Elgar said. “You’ll need it tomorrow. See you then. Usual time, same station.”

“See you, Elgar,” Borden sighed. “Sleep well, now.” With a feeble Gregory Peck grin and a limply Lincolnesque wave of benediction.

Always the second-rate, Elgar thought gloomily, kicking the leprous paint on the stairs as he descended to what he laughingly called home. The Trejour Apartments, which he shared with desperately hopeful sellers of Fuller Brushes and encyclopedias and seedy senior citizens on meager pensions and smearily made-up chorus girls who were not above taking turns onstreet between turns onstage. And his own, private, lukewarm-running psychiatrist. Operating on the margin, like everyone else in the building. Without benefit of license or A.M.A. membership.

He expanded on his theme as he descended to his non-air-conditioned Inferno. Shirts and socks and ties off bargain counters. Ill-fitting “irregular” underwear torturing his crotch, Reduced for Quick Sale lettuce wilting his salads. Elgar bought these things not because he had to, God knew. Because he was compelled to. Because he had been educated early to deserving nothing but bargains: second-run movies, second-hand cars, retread tires, low-octane gasoline. And low-octane girls with pimples, and sorority pins, and brothers who belonged to the American Legion. —Except Sally, who qualified because she was so U she made him feel the requisite amount of discomfort. And Lanie, a first-rater who was determined to live up, or down, to her second-class birth.

Part of the problem of course was that all of Elgar’s girls had to be the kind who would not be after his money. They had to be too kooky and independent (Lanie) or too scornful of wealth (Rita) or too rich themselves (Sally) or just too damned dumb (the rest) to know or care he had it. Elgar had proposed to nearly all of them, and kept proposing, at regular intervals, to test whether he was loved for himself alone. A girl could prove this to Elgar only by rejecting him. So far, all those put to the test had passed.

Continuing his descent he noted that the depressing plastic treads from one of the Seven Branches were missing from half the stairs. The defunct miniature bulb over his door was still unreplaced after two weeks. Jesus! With only half a chance—with only half a houseful of half-sane tenants—Elgar could easily be a better landlord than the owner of the Trejour Apartments. A treasure, indeed. Fit to be buried. Quickly.

Finally fumbling the key into the slot in the pitch-black door and twisting it successfully, Elgar kicked his way into his torture chamber and was greeted by the reeking bag of garbage he’d meant to take out that morning. Reached for the light switch, missed, plunged his hand into an overflowing ash tray. Swore, finally got a light on, and stood there in the midst of unwashed laundry, unread papers, unwashed beer glasses, unmade sofa-bed. At these rents, maid service not included.

There he stood, a monument to the inevitable human condition: surrounded by his own filth. Elgar Enders, heir of the tasteless ages. Worth, at this very instant, a quarter of a million dollars. Worth, at the unpredictable and joyous instant his old man’s heart stopped beating, a half-dozen millions. Currently the possessor of thirty dirty pairs of thirty-nine-cent F. W. Woolworth socks, and not a single clean pair, and unable to do better by himself. Couldn’t do anything better right now than penance.

But couldn’t stand the place right now, either. Not until he was close enough to unconsciousness to sleep anywhere, in the handiest cozy gutter, even in his own apartment if necessary. Achieving the desired comatosity would require several hours and quite a few drinks.

Might as well be consistent about the pattern, Elgar decided. Go across town, other side of the tracks, and visit his second-class-citizen girl friend.