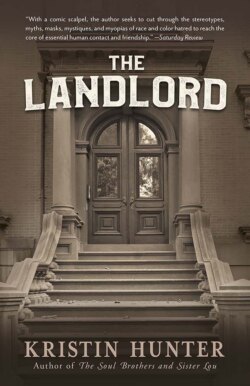

Читать книгу The Landlord - Kristin Hunter - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

Aliquid, cooling breeze kissed Elgar awake from his sound sleep in tumbled, soiled sheets. The first morning of September. End of summer’s slumming. Away with languors and odors. Up then, and singing, even though the singing be hopelessly off key.

Elgar obeyed, leaping into the shower with several appalling bars of:

H,

A,

Double r-a,

G-i-n spells Harrigan.

—Or does it? he wondered as he toweled briskly.

Proud of all the Scottish blood that’s in me,

Divil nor man can say a word agin me.

To a tune strangely resembling “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.” Mothaw tried to make me musical. Lord, how she tried. An effort of a massiveness equaled only by her monumental failure.

Out again, scrubbed and shining, to select a tie. Wrinkling the fine, sensitive, aristocratic nose against yon paper bag with aromatic contents, waiting patiently by the door. Remembering to give thanks for small favors, such as one remaining clean set of underwear.

He put on his brightest blue tie, to stabilize his sea-change eyes. His eyes, like everything about Elgar, were fluid, desperately in need of anchors. He preferred them sky-blue for happiness, though wore green ties on mean days, gray ones on hopelessly bleak days.

On the dresser beside the tie clip (stainless steel, fifty-nine cents, Mothaw’s gold gift—one long lost) lay the four rent books, unopened and uninscribed except for the four hopeful names on their covers.

This was the day he meant to write in each of them, Received of for one month’s rent payable in advance the sum of, and his signature. (And show good cause, Mr. Copee, why it should not be written in your blood.) On second thought, a green tie might be the best choice.

Rent books and trusty Waterman tucked in breast pocket, Elgar swung out into the street and across to the air-conditioned igloo where he breakfasted. The D-R’s chilly interior featured a white formica counter, booths and stools with white plastic cushions, all surfaces frosty-painted and disinfected. And Lanie, capably poised behind the counter in uniform like a tall Supervisor of Nurses.

Might as well let her know immediately that the patient had recovered. “Scramble two light,” he said. “Extra cream in the coffee.”

Her eyelids, with lavender circles above and below, parted wanly. That must have been some all-night songfest and gabfest. “Don’t you want toast, Elgar?”

“No. Watching the old waistline,” he said, and patted his iron middle.

Not one to give up easily, Lanie slammed a large orange juice down in front of him. “What was the big fat idea, running out on me last night?”

Sipping, he said, “Oh, you seemed to be having fun. I’m no music lover. Besides, I had to get up early this morning.”

“Projects?”

“The project. On Poplar Street.”

“Oh. In that case you’d better have some brandy in the coffee,” Lanie prescribed gravely, and reached under the counter for the giant battered mail-pouch she called a handbag. Inside he knew was a cunning little flask, dark-blue glass and filigree silver.

He held up a warning hand. “No, thanks. Fortification will not be necessary.”

“Whatever you say, Elgar.” As she drew his coffee, steam from the urn flushed her cheeks prettily. “What’s holding up those scrambled eggs light, Lucy? Are you laying them, or what?” With a distracted pushing back of her steamed and discouraged hair, forgetting that she had never given the order. Her partner looked hurt, but instantly put butter on the grill and began joyous beatings in a bowl.

“I tried to win Marge over to your side, Elgar. I used every argument I know. But I can’t promise you she’ll do anything for you. She’s had a rough time lately. All of your tenants have had rough times.”

“Don’t you think,” he said, “there may be another possibility, one you have not yet considered, Lanie? That I, myself, may be equal to the problems involved?”

“I think,” she said, “you were a damned fool to get involved.”

Those words, precisely, were Levin’s on the phone two hours later.

“Yes, I said a damned fool. That was what I said, Elgar. Check. What was the matter with those municipal bonds I told you about last week? What, Elgar, did you find so repulsive about Allied Preferred? And if you were determined, really determined, to get into real estate I could have gotten you mortgages. Six per cent, guaranteed.”

It’s hopeless, Levin, Elgar thought. I could shout at you all day, still you’d never understand my needs. Aloud he said, “Levin, a mortgage can’t talk to you.”

“It can’t throw a spear at you, either. Check? Or did I misunderstand you when you said that was what happened this morning?”

“No,” Elgar said. “No, you did not misunderstand me. No, Levin, your hearing checks out one hundred per cent accurate. Perfect.” He hung up and left the glass cubicle, fiendish fishbowl making private agonies public, to sit on the curb, supporting heavy head in hopeless hands.

Fanny, more tempting than ever in tight pink lace, had met him at the door, hair soft and sweet, voice crooning to match, promising reason. She had, she said, a job. And would get paid the following Thursday. The Cumbersons, she continued, would get their pension check at the end of the week, on Thursday or Friday. It was only necessary to catch the old man before he went out drinking on Friday night. And he was not to believe any of Professor DuBois’ stories—that man had loads of money, especially on Sundays. His habit being to take up collections in churches all over town to further the work of higher learning, he would hit at least ten churches between the eleven A.M. tolling for services and the dismissal of Bible classes at three, clearing fifty dollars easy. As for Miss Marge, she would be good for her rent next Wednesday. Not tomorrow but a week from tomorrow, every other Wednesday, that was when the lady she worked for got paid.

“So all you have to do, Landlord, is come back Friday, Sunday, next Wednesday and next Thursday.”

“But this is Tuesday!” he’d howled. “What the hell am I suppose to do today?”

Her rather grotesque suggestion elicited a reply in kind from Elgar. Soon their conversation was blazing merrily in the vestibule, a ball of fire tossed in spirited fashion between fishmonger and fishwife.

Unfortunately the vestibule was not soundproof. Though to judge by her expert use of language, Fanny could take care of herself nicely on any waterfront in the world, Copee came to his wife’s rescue.

The vanishing American had vanished today, but this provided small reassurance. Copee was, Elgar gathered, only part Indian, and today he had reverted to pressing the cause of his other ancestors, and sporting their garb, a majestic swathing of brightly printed cotton. Apparently the vengeful African was his favorite role. He moved easily in bare feet and batik toga, and his awkwardness with a tomahawk was no cause for complacency, judging by the expertise with which he hefted a six-foot spear.

But just in case, backing him up with a baseball bat was his and Fanny’s older darling, Willie Lee, a lean little warrior with mean little eyes that suggested there was nothing whatever left to teach him in school.

They stood arrayed against him, Fanny with sloe eyes blazing, her husband menacing in his gorgeous robes, and their redskinned, evil-eyed son—an exotic tribe who did not look exactly like Negroes, or Asians, or Indians, but like a blend of all three. A new breed, stranger than any of its components, and more sinister.

“Uhuru!” cried Charlie with a deft, sudden gesture that confirmed Elgar’s suspicions that he was no stranger to spear-craft. “Out of my house, on the double, invader! Uhuru!”

“Freedom!” piped little Willie. “That means, ‘Freedom now!’ Mister, you better go.”

“Howdy,” said Elgar wearily. “I was just leaving.” He turned and descended the steps just as the shaft swooped overhead with rocketlike grace.

Now, trying to forget the unfortunate incident, he became absorbed in the morose progress of a frail white candy wrapper down the gutter. Caught up in the whirls and eddies of last night’s rain, it bobbed, backtracked, struggled weakly, drifted sadly sidewise, finally sank down the corner sewer, reminding Elgar all too forcefully of his likely future progress. If present currents were any indication.

For a bit of cheering contrast he thought of his older brothers: Moe, a thriving banker, and Shu, now happily managing three of the Seven Branches. Each had progressed easily and logically from the standard schools to junior exec jobs to management, acquiring on the way the standard one skinny wife and three fat children. Could either of them, with their perfect sense of order and sequence, ever possibly get into such a hopeless situation? And, if the impossible occurred, could either fail to become extricated, smoothly and with a handsome profit?

No, he knew, was the answer. To both.

There remained his father, Julius Pride Enders. Old Iron-fists himself, the King of Merchant Princes, with his standard solutions to the problems of Holding Your Own and Getting Your Return and Giving the Peasantry What They Want While Keeping Them in Their Place (Down). Applied to limited questions, Fathaw’s answers were remarkably successful, though. No doubt, if Elgar phoned him, he would have a good suggestion or two for Holding Your Own Under the Present Shaky Conditions. But at the thought of calling Fathaw and asking, “What do you do when the peasantry hurls spears at you?” Elgar’s stomach refused to stay in its place, became an angry jack-in-the-box demanding its own Freedom Now.

Elgar had demonstrated his own imperfect sense of sequence by taking up a series of undistinguished occupations—forester, stable hand, horse-farm manager, construction worker, building contractor, bum—while postponing plans to study architecture, plans to study law, plans to go into real estate, plans, plans, plans. The current abortive attempt at real estate would be viewed by now as an unfunny family joke. The latest illustration of his disappointing failure to jell as solidly as citizens Moe and Shu. Who every day in every way, mental and physical, in their small boxes of offices and their large, boxlike, eighteenth-century houses, were growing squarer and squarer. While Elgar, still suffering from a constitutional inability to shape himself along cubical lines, knew of his future only what he had always known: he could not stand to be like them.

This knowledge, however, was a frail stalk to depend on for support in one’s upward climb from the gutter. For, if he was not like his brothers, who or what was he?

Elgar’s reflection on glass panes, as he fled back into the phone booth, was a silvery, ghostly blur.

The minute he heard Fathaw clear his throat at the other end, Elgar knew it had been a serious mistake to call. That harrumph, the backfiring of a twelve-inch cannon, announced a heavy forthcoming barrage.

“What’s the difficulty this time, Elgar? Haven’t Neeby and Levin been following my instructions?”

Neeby was the Trusts and Investments man at Moe’s bank, and his instructions were to turn certain regular sums over to Levin, who had his instructions on how much to invest and how much (a trickle) to release to Elgar. Steel-eyed Levin watched fish-eyed Neeby, and Neeby watched Levin, and Fathaw watched them both, and they both watched Elgar. Oh, it was a pretty, pretty net in which they had him dancing like a deranged butterfly, balancing his doom against his father’s.

“Are you still seeing that crackpot talking doctor, Elgar?” Fathaw’s respect reached out to encompass all solid things like land, figures, prime ribs of beef and machinery, but withdrew contemptuously from anything so slippery and limitless as talk.

“Yes,” Elgar squeaked. “Yes, Fathaw. He’s helping me.”

“Well, why in hell do you need help? You’re crazy. I mean you’re not that crazy. All you need is a good hard job. A stiff upper lip. Some good fresh air in your lungs. Why don’t you get away from it all? I mean camp out in the woods, rough it, don’t waste money on one of those expensive resort vacations. Go up in Canada with your brothers and bag some deer.”

The standard answers, with the standard reference to curbing expenses which always occurred in the first thirty seconds of Elgar’s conversations with his millionaire father. Also the standard suggestion about hunting, which Elgar always ignored, out of a conviction he was bound to fail, being essentially on the side of the deer.

“Why must you always assume there is a difficulty, Fathaw? I called to ask what you know about real estate.”

“What do you mean, ‘what I know?’ I know everything about it, of course. Know real estate like the back of my hand. That tract along the Upper County line. Built a shopping center up there recently. Now developing a town around it. Endersville. What’s Levin suggesting? Mortgages?”

“Why must you assume I act only on Levin’s suggestions? No, an apartment house, Fathaw. My own idea.”

“Tricky business, apartments. More nuisance than profit. Anyone who would rent a place to live is a gypsy. A vagrant. Miserable, dirty little people. No sense of responsibility. Wear and tear on property. Precious little return on your money. Bad business, Elgar, for anybody except old men and widows. And you know I don’t consider anyone old till he’s passed seventy-five. My time is money, you know. Real estate’s a large subject. Don’t be vague. What’s your problem?”

“The fact that you’re not even past sixty-five,” Elgar whispered into the phone, his clenched fist poised to drive through the nearest pane of glass, the one that held his own vague reflection.

“What?” the old man bellowed. “Speak up, will you?”

“The fact that as yet I’ve derived no income from this property. Have you any thoughts on how to collect rent from tenants?”

“Put it in the hands of a constable! Give them thirty days! Let him evict them!”

Put your problems but not your money into someone else’s hands. Another standard answer which had worked well for Fathaw all his life.

“I don’t want to do that, Fathaw. I want to handle it myself.” Even as he uttered this plea he knew it sounded ridiculous. As when once he had pleaded, “Let go of the bike. I want to ride it by myself. Even if I fall flat on my face.” Which, of course, he had done. His stomach went into such acrobatics at that point, Elgar had to put his head between his knees.

“Elgar,” said the stern voice at the other end, “where exactly is this property of yours?”

“Right in the center of town here. Corner of Jackson and Poplar Streets.”

“Elgar. Isn’t that a colored neighborhood?”

“It seems to be,” Elgar admitted. “Yes, Fathaw, that’s what it seems. Of course,” he added, “as you know, Fathaw, all things are not what they appear to be. My tenants refer to themselves as Creoles and Choctaw Indians. And sometimes, I believe, Nigerians and Senegalese.”

“Elgar, you are even more of a fool than I thought!” roared his father. “Nigerians, indeed! Your mother and I are simply at our wits’ end about you, Elgar. She worries about you constantly, about your bad habits, your foolish ventures, your undesirable companions. Frets night and day because you never visit us and never call. While your brothers are such loyal sons. What a contrast. I never know what to tell her about you. I never even know where you are. This nonsense of yours must stop, sir, do you understand? It must stop right now! I am going to put your mother on the phone in one minute. But first I want to know where you are, Elgar. I mean where you are right now. We’re coming down there to get you.”

“I am in Hell, Fathaw,” Elgar said simply, and hung up. And, retracting his hand at the last instant, slammed the receiver through the nearest pane instead. Showers of glass sprayed his face, miraculously missing the dangerous-glinting green eyes.

Hurrying numbly through dim streets to keep his scheduled appointment with Borden, he was only vaguely aware of moisture tickling various upper frontal areas. Hence when the good doctor received him with cracks in his professional composure, with his mouth, in fact, wide open, Elgar was surprised.

Until he reached up and touched his forehead. His fingers came away bloody. Touched his cheek. Also bloody. His upper lip yielded another harvest of gore. Apparently the scattering fragments of glass had made him as monstrous as his father’s vision of him.

“Just following my father’s advice, Borden,” Elgar said. “He told me to acquire a stiff upper lip. And it does seem to be getting numb, now that I notice.”

Borden stared. “Elgar, I know you love to be dramatic, and I have my rules, but this seems to be an emergency. If you want to see a doctor about those cuts, I can reschedule your appointment.”

“Funny, I thought you were supposed to be a doctor, Borden. You great big phony. Upset at the sight of a little blood.”

Borden said smoothly, “It is not so upsetting as all that, Elgar. All the same I am willing to delay your hour for fifteen minutes if you want to go downstairs and wash up.”

“No, let’s get right down to business,” Elgar said. “I can stand it if you can.”

Borden replied, “You should know by now that I can stand anything, Elgar. Come in.”

“However,” he added, opening a cabinet to reveal a businesslike assortment of swabs and syringes, “there is no reason why I have to spend the next hour contemplating physical horrors in addition to psychic ones. No. Tilt the face up to me, Elgar. Turn it toward the light. Yes.”

Borden’s fingers were wonderfully deft and confidence-inspiring as he dabbed lightly with antiseptic, peered closely, grunted, bent with tweezers, and removed several splinters of glass from Elgar’s scalp, finished by making rapid passes in the air with a roll of bandage.

Afterward Elgar went over to the mirror and checked. His head was neatly swathed and tied like the kid’s in “Spirit of ’76.”—Yep, he thought, puckering his chin thoughtfully, yep. A professional job.

“Are you quite finished admiring yourself?” Borden inquired. “Then perhaps you will want to lie down over here and describe this latest hair-raising episode. Or should I say, ‘scalp-raising?’ You say it resulted from a conversation with your father?”

Elgar stretched out and studied the dismal patterns on Borden’s mildewed ceiling. “You know I can’t talk to my father, Borden. It’s impossible. He always tried to make me feel like nothing.”

“Apparently he succeeds,” Borden observed. “Since, following your conversations with him, you always attempt to destroy yourself.”

“Aaaaaah!” was Elgar’s only comment. That and a pummeling of the couch.

“Yes. It is better to destroy my couch, Elgar. Though even better if you take out your aggressions on appropriate objects. Have you noticed, Elgar, that you have no trouble reacting with anger to any person except your father?”

“Oh, have I ever noticed,” Elgar declared passionately, unconsciously echoing Borden’s speech pattern. “Oh, brother, have I ever. Yes. Yes yes yes yes. When I talk to him I don’t feel anything but weak. That and stomach pains.”

“Which are, as we know, your way of feeling anxiety, Elgar. Stomach pains are anxiety, nothing more. There is nothing physically wrong with your stomach, as you know from having swallowed quantities of barium. As well as a number of even nastier concoctions in your various attempts at suicide, with remarkably limited results. Yes. Your stomach is actually an organ of fantastic recuperative powers, deserving of study by science, Elgar. Now tell me. How does your father achieve his annihilation of you?”

“He hasn’t yet,” Elgar said quickly. “I’m still here. Don’t you see me here, Borden?”

“Of course,” Borden reassured him. “I mean your psychic annihilation. How does he make you feel like nothing?”

“By knowing it all!” Elgar howled. “By having a formula for everything! By being so successful, he is everything!”

“And yet you know that statement is untrue, Elgar. Your father is not everything. This room, for instance, this desk, this chair, they are not a part of your father or his holdings.”

“You don’t know Upper County, where I come from,” Elgar said grimly. “Up there, they would be. There’s nothing in the whole county he doesn’t own.”

“I see,” Borden said. After a pause to formulate his thoughts he announced, “Elgar, I think we have found the key to your identity crisis.”

“Turn it!” Elgar cried. “Open this box I’m in. Tell me who I am.” Adding bleakly, “Unless I’m nothing.”

“No, Elgar, you are not a nothing,” Borden said.

Hope shining through hopelessness, Elgar looked at him.

“You are an anti-everything, Elgar. Engaged in a vast crusade that dissipates all your psychic energies.”

Elgar bared his fangs to growl at Borden’s jargon.

“Wait, Elgar. Let me put it this way. You come from a powerful family with a totalitarian father who insisted that everything be done his way. Who even insisted that his children grow his way, as if you could make a birch sapling become a sycamore. As well as a mother who imposed her musical and other standards upon you, even sending you to a girls’ ballet class. Yes. Your mother is another totalitarian figure. With her loud and constant insistence that your father is never wrong.”

“It gets louder the wronger he is,” Elgar said, and clutched his stomach. “Ouch!”

“Yes, it even hurts you to admit he can be wrong. Growth, Elgar. Painful. Yes. So you spent your childhood being something other than a sycamore, being a birch, perhaps, trying to grow big and strong enough to stand independent of all that Establishment—your father’s estate, his enterprises, his millions, and all the powerful people who support him, including your mother and your obedient brothers. You wished to be a person, not a Representative of something you disliked. You were, we might say, a birch, but no Bircher, Elgar. But, to continue this rather appalling image, you are still only a slim sapling, and every time you spring up in your own form, your father slaps you down. With the force of a giant woodsman. A Paul Bunyan.”

“That’s right,” Elgar said, nodding, reacting to his own fate more calmly than he would to an unfavorable weather prediction. “Yep. That’s how it is.”

“Is that all you can say? And in that tone of meek submissiveness? Elgar, what would you say should be the normal reaction to a person who carries out this systematic total destruction of another person?”

Elgar at least knew his lessons well. “Rage,” he said, almost feeling it. “White hot, scalding rage!”

“But when your father attacks you, you feel—?”

“Nothing. Absolute, pure, numb zero. Less.”

“And the rage only comes later?”

“Much later.”

“And turned, always, on yourself. Yes. To the point of self-destruction. Which is why, Elgar, we have agreed that contact with your father is dangerous for you at present. At your present stage of maturity, even to telephone him is an act of self-destruction.”

Borden paused before dropping the awful question into the silence. It shook the room with the force of a boulder.

“Then why, Elgar, did you phone your father today?”

“I didn’t say I phoned him, Borden,” Elgar replied stubbornly, fighting back his unreasonable fear of being caught. “How do you know? Maybe he phoned me.”

Borden simply stared back at him quietly, that calm, empty stare which at times drove Elgar to fits of frustration. And, at other times, to fits of honesty.

“Yes, Borden, I called him,” he admitted finally. “You sad imitation of Basil Rathbone imitating Sherlock Holmes, you know he couldn’t have called me. He doesn’t know where I live, hasn’t been able to find me since I holed up here in the Trejour. So yes, Borden, I admit it. I walked into that sidewalk phone booth, that elegant glass coffin designed by Mies or somebody like him so all the world could watch my death throes, and put the coins in the box, and dialed my father’s number myself. Why did I do that, Borden?

“—Because the tenants at my apartment house are driving me out of my mind. I haven’t collected a cent in rents from them. I’ve collected nothing but abuse. I thought maybe the great Empire Builder would have a suggestion to help me clear up my minor problems with a small empire consisting of only four measly apartments. But he was no help at all, Borden. So I smashed my way out of the booth again.” Christ, he was crying.

“You wanted him to be helpless,” Borden suggested. “You wanted your father to meet with a defeat. It is what you have always wanted, Elgar. At the cost of your own life, if necessary.”

Tears really flowing now. Stop bawling, he thought, you’ll ruin the bandage, lying prone like this. Shut up or sit up, you slob.

“Elgar,” Borden said softly, “I think it is too high a price to pay.”

Funny, how Borden was really getting to look like Lincoln. Like the Old Emancipator himself.

“To summarize,” Borden said with an elevated bony finger, “you feel a strong desire to kill your father. You can’t stand this idea, so you try to destroy yourself instead. But you are getting better, Elgar. Today you only sliced yourself up a little. Also, I think you no longer need your father or his advice. I think perhaps you can arrive at your own solutions, now that you have made a beginning.”

“Please, Borden, tell me. Where in the crazy mixed-up mess of my life do you see a sign of a beginning?”

“Buying this apartment building. Taking on new responsibility. I think it is a healthy project for you, Elgar. I think you can use it to work out many of your problems.”

Borden glanced at his watch. It usually angered Elgar that he should never fail to notice the end of what must surely be the most fascinating hour of his day. However, today Elgar’s rage, usually his trusty ally in every situation but one, had deserted him.

“Your hour is up for today, Elgar. I suggest you go back to your property and attempt to collect your rents. If you meet with resistance, take out your aggressions on your tenants. That will be good for you. And it will be appropriate.”

Smiling bravely if wanly, the bandaged old warrior saluted his commander-in-chief, tottered out of command headquarters, and made for the front lines once more. To faintly fluting strains of “Yankee Doodle.”

An hour later he was back in his barracks, staring distrustfully at a small, gaily printed white card. It had been far too easy. His instincts smelled a trap. Yet there it was in his hand, frisky and friendly as an innocent lamb.

This time Marge had come to the door to announce that she was the duly elected president of the newly formed Corner Poplar Street Tenants’ Association, and therefore authorized to speak for everyone in the house. The C.P.S.T.A. had held its first meeting today, she said. In addition to the election of officers, they had aired their grievances and come to an important decision.

“What goddamned grievances?” he’d asked in disbelief.

“We’ll get to those later, Landlord. But I can tell you one complaint was about foulmouthed language on the premises. Yours. So just be quiet and read this. Here.”

The card she handed him said:

Does your blood feel tired, does your back feel bent?

Help us raise the roof while we raise the rent!

There’ll be Fountains of Youth * and lots of eats

At the corner of Jackson and Poplar Streets!

| FRIDAY EVENING, | *(ALCOHOLIC CONTENT) |

| SEPTEMBER 4TH | ADMISSION TWO DOLLARS |

8:30 P.M. ’til ???

“We used to have these lots in the old days,” Marge explained proudly. “The rent comes due every week in Harlem.”

“Well,” Elgar said, smiling all over himself, even under the bandage. Pleased and shaken. “Well. What do you know? A party. Well. Am I invited?”

“Well of course, Landlord,” Marge said, with indignant hands on her wall-to-wall hips. “You’re the reason for the party. There wouldn’t be any party except for you.”

“Yeehoo!” he howled, ripping off the bandage like an imaginary ten-gallon hat and doing three rapid battements élevés between the top step and the sidewalk. “Whee! Yoohee!”

“There will be no rowdy conduct allowed,” Marge said severely. “And you got to pay your way in the door, just like everybody else. After all, this is a rent party, Landlord.”