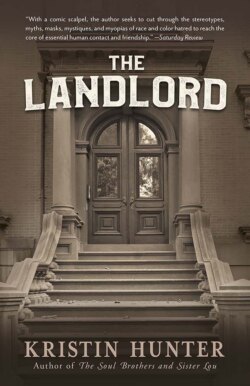

Читать книгу The Landlord - Kristin Hunter - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Elgar Enders patted the four new, crisp rent books in his pocket with tender satisfaction. At last he had a business: Real Estate. An occupational title: Landlord. A piece of property, described in a deed with fine legal exactness: Three stories, four units, so many square feet on a lot one hundred by fifty, valuation for tax purposes, twelve thousand dollars.

Elgar almost crowed, and leaped, and clicked his heels in the air until he remembered that he was out on the street where Mothaw browsed every Monday for bargains in emeralds, the calm, stately street, surrounded by cool, contained people. On a bright, beamy Monday in August, hint of breeze.

Well, now he would be contained too, for at last he had work, something to do with his continually itchy, troublesome self. There would be locks to replace, drains to unclog, light fixtures to repair. He might, at long last, allow himself the luxury of a few choice gripes, in the fine tradition of all workingmen since the beginning of history. As a hobby, he might even gather a compendium of colorful complaints—the howls of London hod-carriers, the steamy swearings of Roman pasta-makers, the mutterings of hordes hauling stones to the Pyramids.

—By the sickly lusts of our incestuous Queen, you are a sodomous son of a jackal-faced dog, you Nile-moldered hunk of rock, you.

Yes, drains were solid problems, the solving of which produced tangible results, unlike those vague, cloudy daily exercises with Borden, his psychoanalyst, or those metallic dialogues with Levin, his stockbroker:

“Aluminum Alloys, keep, check?”

“Check. It’s holding steady.”

“Overseas Pipeline, sell, check?”

“Check. It’s loosening up now.”

“Sell Supersoft Mills, too, Levin.”

“No, don’t sell Supersoft, Elgar. It’s firming up. Check?”

“Roger, Levin.”

Never, never, “And how are you today, Elgar, my boy? Loosening, steady, or firming up? Loosening? I know exactly how you feel, man, I have those days too. Firming up? Fine, congratulations.”

Check. Firming up, thank you, Levin, though you will never ask. With a drain, you knew where you stood. You worked over it long and tenderly, and suddenly there was the satisfying swump, gurgle, swish as it cleared, and you lit up with the holiness of accomplishment, knowing you had done your share in the great work of clearing the drains of the world. Sanitation and sanity. Mens sana et drains sano.

Mothaw would die if she knew her sensitive youngest, her precious downy blondling, yearned to be a common plumbah. And, oh, then he had another happy, eager thought. Maybe Fathaw would die too.

He sang as he swung along, so loudly and tonelessly that a mauveytweed matron, one of Mothaw’s Monday-afternoon concert friends, probably, stopped dead and stared.

“Swump, gurgle, swish, ma’am,” he repeated politely, tipping his hat, and moved on, adding softly, “Go screw. I am happy.”

Elgar felt the dotted outline of his ever-fluid identity filling in, growing almost solid. Catching sight of his grin in a reflecting store window, he tilted his head slightly and patted his thick, buttery hair.

Aha, you handsome dog, you.

Then looked away quickly, superstitiously, lest his image disappear in retribution. He always expected it to, since he was far handsomer than he deserved to be.

God’s gift to women, no doubt about it. Have to share the wealth, spread it around. Sorry, my dear, but ’tis my mission on earth. Who are you to be so selfish?

Someday he would have the guts to say that to Sally, blonde Sally-from-Smith, with her pained look of sacrifice every time she granted him her elegant favors, and to Rita, angry-social-worker Rita, with her dark, stony, Talmudic spells of brooding, and to Lanie, with her constant, lilting mockery. —No, not to Lanie, who was nicer to him than she had a right to be.

“Lanie, are you an octoroon?”

“No, silly, a macaroon. Want a bite?”

Of course he did, he was always hungry, no matter how bitter a draught of guilt washed down his dinner. And, no doubt about it, the sight of him curled up next to that golden cornucopia would be just the ticket to send his old man to sudden, apoplectic death. The intensity with which this consummation was desired was probably what tightened the knot in Elgar’s stomach so viciously, doubling him over on the street. There was nothing organically wrong with him.

“All right, Elgar.” Borden, with the goddamn kindliness in his voice, puff-puffing on the pipe. “Let’s be honest, now.”

“Certainly, Borden, though if you insist on playing this like a gentleman’s game, a Christly hour of chess or something, it won’t be easy. But if you want honesty, Borden, to tell the truth, it’s a fake, that bit about my spreading the wealth. It’s more a case of covering my bets, you see. I have to have lots of women, because if I concentrate on one, when she leaves me, I’ll be alone.”

“Alone and worthless?”

“Yes, Borden, you bastard.” Oh, yes, I’ll have a thing or two to tell you this afternoon.

But first there was lovely, solid stuff to buy. A two-inch copper joint, weatherstripping, a set of wrenches. —And I’ll take a set of wenches, as well. The very best you have.

But how much weatherstripping? Take a chance, guess, or go measure all the windows?

“Waste not, want not, son. Get it right the first time.”

“All right, Fathaw, I hear you!” he screamed. “I’ve been hearing you all my life!”

He stopped and stared fiercely at three startled passersby who averted their eyes, then took up their directions again, jerkily, like frames in a movie reel that had been momentarily frozen. Elgar laughed maniacally—Make way for the madman—and moved on beyond them, beyond weatherstripping, to dreams of his house of the future.

One day, the present tenants gone, he would strip the place of its apartments, remake it into the residence he would by then deserve. By then he would be able to allow himself a pleasure palace arranged to permit the endless play of light on textures and furnished to indulge all the whims of a restless, robust mind. Then he would leave his dank death-cell in the Trejour Apartments, no longer needing Borden in the same building to reassure him, tell him over and over again that he was real, and good, and deserved things. There would be no more screams into the phone in the middle of the night.

“Borden! Borden, are you up there?”

“Yes, Elgar.” —Always patient, even when awakened at three in the morning. Couldn’t he ever get upset? “I’m here, and you’re there, aren’t you?”

“Christ, I know I’m here, you incredible idiot.”

“Good. Then good night, Elgar. Go to sleep.”

The click, and Elgar would let loose a stream of spluttering curses, yet be somehow satisfied by the exchange, and able to sleep at last.

Someday he wouldn’t need Borden always handy to shore him up and undermine him at the same time. Steadying him with his right hand, while with his left he was draining Elgar of dreams and memories, making him paler, pushing him toward disappearance. And charging him twenty-five dollars an hour for the bloodletting.

Elgar sucked in his breath, squinted his eyes shut, and concentrated on seeing the house as it would be someday. His house, an extension of himself, in that fine future when he would have a self to extend.

. . . Rip out the stairs and partitions, recess the second story into a gallery bedroom opening on a balcony, give the first-floor living room a three-story cathedral ceiling. One starkly beautiful light fixture that he would commission, a dancing constellation of lights visible at night through three stories of glass. Of course he would have to curtain that fall of glass, at from twenty-five to fifty bucks a yard, and . . .

His father’s hand, pinched with penury in the midst of its millions, unable to replace anything until it frayed and fell apart, clamped down clawlike on Elgar’s before it could react to the lovely, crunchy feel of that fabric. An unbelievable shade of goldy-green, it slithered away into the dank subterrain of dreams that would never be realized.

Certainly nothing so lush and lovely would ever see the light of day on the cut-rate counters of J. P. Enders and Co., Seven Branches, Never Undersold. From all seven branches a clammy sea of plastic billowed forth endlessly to curtain the world, for J. P. Enders was the Junk Emporium, and he, Elgar Enders, was the son and heir of the Emperor of Junk. Try as he might, he could not abdicate the throne.

Measure he must.