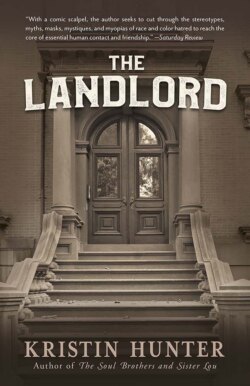

Читать книгу The Landlord - Kristin Hunter - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Even at a distance Elgar’s house stood out from all the others, rising tall and clean as the Washington Monument from a surrounding shambles of shingled lean-tos and upended brick coffins, with the good balanced architecture that had sold him, wide, well-placed windows, a fanlighted prince of a door.

The real estate salesman had assured him, over and over, that the tenants were good, steady, reliable types. None had lived there less than five years. One couple had been there twenty-five years.

He’d added, with odious chumminess, “Can you imagine the ignorance of those people? By now they’ve paid enough rent to buy the house four times over. Best value on our list, too. I approached them, but they weren’t interested. That’s why I prefer dealing with a businessman.”

—A white man, you mean, had been Elgar’s reaction. And I suppose, since slimy reptiles like you also come under that classification, we are expected to have everything in common.

He’d bought on the spot, rather than submit to the rest of the salestalk. No need for dickering, anyway. It was a good buy.

—An excellent buy, he amended, moving closer to admire the gracefully proportioned windows. Congratulating himself on his astute judgment of property values, his shrewd eye for a bargain, Elgar almost overlooked a startling new development.

Each window now contained a large, boldly printed sign.

What the hell?

Elgar kicked the front door open and stormed into the vestibule.

“This property is not zoned commercial, do you understand?” he raged. “It’s residential!”

In the vestibule, a brick-complexioned dwarf with a curly black mop regarded Elgar blandly from its perch on a fire-red scooter.

“I Walla Chee Cho Chee,” it chirped. “Gimme nickel.”

“Who is Madam Margarita?” demanded Elgar. “Where does Fanny live?”

“I Walla Chee Cho Chee,” the dwarf repeated sweetly. “Gimme nickel.”

“Oho,” said Elgar. “An extortionist. I know your type. Just why should I give you a nickel, Walter Shoji? Just because you have the largest, darkest, most lamplike eyes I’ve ever seen? Don’t you know that’s the beginning of creeping socialism? Don’t you know how bad socialism is? Do you want to grow up without a shred or particle of individual initiative?”

It was a good imitation of Fathaw, even to the rasping whine in the voice. Elgar held up a shiny dime.

“On the other hand,” he lectured, “let me demonstrate to you the advantages of earning your bread. You see this? This is worth two nickels. And it is all yours if you will tell me which apartment belongs to Madam Margarita and which to Miss Fanny.”

“You the new rent man?”

“Never mind who I am. I am your Uncle Sam, if you must know. Who are Margarita and Fanny?”

“Don’t know no Marita. Fanny my mama. I Walla Chee Cho Chee.”

Or something like that. Then, in a maneuver that would have done credit to an Olympic skiing champion, the kid leaped, plucked the dime from Elgar’s fingers, and sailed out of the door on his scooter.

“Gone buy me two green yum-yums,” he tossed over his shoulder. “I love green yum-yums. Yum-yum man, he go soon. I hurry. ’Bye, rent man.”

There was such lyrical sweetness in the voice uttering this foreign-sounding babble that Elgar was suddenly homesick for the South Sea islands he had never seen, until he realized how thoroughly he had been tricked.

He turned helplessly, masticating his rage, and studied the names which were variously scribbled, printed, and embossed on the mailboxes. Copee. Perkins. Cumberson. And, in raised gold script letters, P. Eldridge DuBois. Elgar copied each name onto the cover of a separate rent book, using the laborious block printing that was the only thing he had taken away from his desperate years at day school. That P. Eldridge character. Hmmm. Elgar smelled trouble there.

He went outside again and stared at the signs for a full five minutes, deliberately allowing his fury to build to a molten froth as he read:

Madam Margarita

Readings $2

Ring 2 Bell

(If No Anser Ring 1 Bell)

and:

Fanny Hair Styling

$3 Up

Ring 1 Bell

(If No Anser Ring 2 Bell)

Obviously, there was collusion at work here. A conspiracy among his tenants to ruin him. Elgar went back into the vestibule and rang all the bells. Simultaneously, steadily, with the full, unforgiving pressure of his arm.

There was an immediate response that made him jump. It came from the third mailbox, the only one which boasted a tricky little microphone and speaker. Out of this elegant, custom-installed device came a click, the spooky burr of static, and then a crisply insulting, British-style voice.

“State youah business, please.”

“What?” roared Elgar. “Who the hell are you?”

“Dubwah heah,” the gadget replied silkily. “State youah business.”

“Well, Mister DuBois, you’d better state your business. I am the new owner. Do you know anything about those signs out front?”

“I do not participate in the vulgar activities of this establishment, suh,” was the suave answer.

“Well, do you participate in vulgar money-making activities, like the rest of us? Readings, for instance? Or Hair Stylings?”

“I, suh, am a Creole,” the device answered, settling the question forever.

“I don’t give a damn what you are!” Elgar bellowed. “You better pay your rent American!”

The thing was offended. “Rally!” it exclaimed breathily, and clicked off.

Elgar had still not gained admittance to his own house. And, in a typically Elgaresque blunder, he had left the keys at the real estate office. Biting his lip to contain a really royal flow of curses, he folded his arms and leaned all his weight against the bells.

In response, a blur of crimson like a full-blown anemone exploded into the vestibule.

“Where’s Walter Gee? Have you seen him?”

Scarlet silk emblazoned with golden dragons, slippery and, he hoped, precarious, was the only covering of the softest, smoothest expanse of beige skin Elgar had ever seen, and Elgar was a connoisseur of such matters. You could drown in skin like that, and die happy.

As his eyes slowly traveled upward, a rounded knee obligingly peeked out from beneath the robe. Elgar’s eyes halted there. It was a long time before he reached the face, but that was satisfactory too. Adorable, in fact, if you had a taste for the exotic. Slightly Mongoloid features, almond-shaped black eyes with a flat, exciting glitter, shaded by lashes that almost swept the floor. Now batting at the rate of eighty bats a minute. Helplessly, fatuously, Elgar smiled.

“Where is Walter Gee?” she repeated crossly. “Mister, have you seen my little boy?”

“There was a kind of a pygmy con man hanging around here when I came in,” Elgar replied. “He got a dime out of me and disappeared.”

“Ooh!” she shrieked. “You gave him a dime? To buy that nasty green Wop ice cream? A dime’s enough for two of those things. He gets sick to death from one. If I have to take him to the hospital, I’ll sue you.”

“How much?” Elgar asked, thinking, Take it all, take everything I’ve got. It’s yours, if you’ll just let that robe slide down a little lower on the left side. Ah, there.

She ticked it off on her fingers. “Ten thousand for damages to my child’s life and limbs. Ten thousand for court costs and lawyer fees. Ten thousand for medical expenses. Ten thousand for my mental anguish, and ten for my husband’s mental anguish. That’s fifty thousand dollars if he don’t die. If he does—”

She looked up at Elgar suddenly, the lashes batting like moth wings, the eyes beaming an expression soft and seductive as a Univac’s.

“You’re kinda cute, though. For a white man. Who are you?”

“I’m the new landlord.”

Her eyes widened. “Maybe I won’t sue you, then. Maybe I’ll just settle for five years’ free rent. I’m Fanny Copee.”

“Charmed,” he said. “Always wanted to meet the Dragon Lady.”

She was not smiling. “You go find my little boy,” she said. “Walter Gee Copee. He’s only four years old. Find him quick, before he eats that nasty, rotten green poison. Then you come in and have a little talk with me.”

“Delighted,” Elgar said. “I was intending to have a little talk with you anyway. About, uh, the hairdressing.”

Her hand darted out and brushed Elgar’s hair, sending a jagged shiver to his toes.

“Oh, you don’t need nothin’, Landlord. Except maybe a little dandruff treatment and scalp massage.”

She wiggled her fingers by way of illustration. Elgar giggled helplessly while she looked him up and down, assessing her power. It was complete. Then, by God, she winked.

“I give body massages, too. Real good ones, Landlord.”

Just as he reached for her, she whirled and vanished in a storm of crimson petals. Leaving him to speculate on how a tailor in Hong Kong could have known exactly where to embroider a golden dragon to tantalize him so acutely in America.

Oversexed because underloved, that was what Borden said. A common problem. As if that made it better, not worse. Once the love-index rose, the sex-hunger would fall off.

Meanwhile, his blood stirring, his head reeling, Elgar leaned back absent-mindedly against the row of bells and tried to make sense of things that defied all reason. Haughty Creole aristocrats, scheming Samoan midgets, litigious Dragon Ladies—all, obviously, stark staring mad. What had God wrought? What had he bought? The Mental Health annex of the World Health Organization? The official U.N. nut-hatch?

Good, steady, reliable tenants, my foot. Ooh. Wait till he got his hands on that rotten, lying little real estate agent. He’d wrap his crooked incisors around his slimy fangs, by God; he’d make his mouth resemble the rubbish heap at the Royal Doulton factory.

The vivid details of Elgar’s plans for the real estate agent were interrupted by a rumbling like a locomotive in the hall.

“Fanny Copee,” it boomed, “you get out of the way and let me handle this!”

The owner of the voice flung open the door and steamed toward Elgar, full speed ahead.

“You got till I count to ten. Then you better be off these premises.”

Elgar stared up at the darkest, most massive woman he had ever seen. About six feet tall and four wide, wearing sinister rimless glasses, trembling even more than he was, and pointing a gun at him.

He had always been afraid of the dark, and at the sight of all that blackness coming at him, narrowing and concentrated to the point of the black steel barrel that would finally diffuse his paleness into atoms, something loosened the stopper that kept Elgar’s compartments watertight, and all of his guilty fears flooded down to his knees. He almost desired her to pull the trigger.

“I count fast. I went to the tenth grade in school. So you better move.”

“Wh-why are you pointing that thing at me?” he managed.

“My powers told me evil was coming my way this morning. ‘Expect evil on your doorstep,’ they said, so I was prepared. Get movin’ before I call the police on you.”

At the word “police” there was a toccata of high heels, and Fanny blazed into the vestibule again.

“Police? Miss Marge, have you lost your mind? My Charlie just got back home from his last sentence!”

“Don’t worry, honey,” Marge said. “They won’t be after Charlie this time. This time they’re gonna take away a white man. For breaking and entering.” Marge shrugged. “Though why you want that troublesome husband of yours home anyway is more than I can see. If you had any sense, you’d of let me dispel him for you long ago.”

It had been like this all his life. No one ever recognized Elgar. Everyone refused to grant him an identity.

“But I’m the new owner of this house!” he spluttered.

“Sho,” Marge said. “And I’m the First Lady of the United States.”

“He is, though,” Fanny said. “He’s the new landlord.”

“How do you know, you simple-minded child? Just because he told you? Did you think to ask him how come he ain’t got no door keys?”

Elgar was choking. Gasping for air. “I’ve got papers,” he said. “I can show you.” Then he stopped, humiliated because he again had to prove that he existed. And, this time, to an enraged hippopotamus who probably couldn’t read.

Sure enough, she said, “Papers don’t mean nothin.’ I can’t read.”

“I thought you went to the tenth grade in school,” Elgar said.

Fanny said, “Ha ha, Miss Marge, that’s a good joke on you!”

Marge tossed her a death-ray and muttered, “Dumb teachers didn’t know the right way to teach me. It was their fault, not mine. You better not get smart with me, you loiterer. Not in my vestibule.”

“It’s my vestibule, I think,” Elgar insisted weakly.

The large, shadowy menace moved toward him, blotting out what little light remained, and touched the point of the gun to the third silver fleur-de-lis on his blue tie.

“You tryin’ to take advantage of me because I’m a woman?”

“Believe me, Madam,” he assured her warmly, “it is the farthest thought from my mind.”

“Well, don’t try it. I’ve counted to ten three times. By rights you’re dead already. You’re a ghost. You hear?”

It was far too close to Elgar’s actual feelings about himself. He was fading fast when rage, the only strong and dependable emotion he knew, saved him.

“I am no ghost and no loiterer, either. I am the legal owner of this property. And right now I am planning legal steps to evict you, if you don’t immediately put away that illegal weapon.”

“Take more than a dozen little boys like you to evict me,” was the serene answer. “I been here fourteen years. I expect to be here another fourteen. And without no constant doorbell ringing to disturb my concentrations, neither. This is my house. You’d better be on your way out of it right now.”

“It’s my house, I own it,” he half sobbed. As, once, into Mothaw’s ironclad lap. “I paid money for it. Lots of money. That’s why I own it. That’s why it’s mine.”

“Oh yeah?” she said with amused tolerance. “What else do you own?”

“Three cars, two motor scooters, five horses, a stable, and five hundred shares of General Motors.” Oops, time to call Levin.

“I have to call my stockbroker right now,” he said, and lunged towards the hall, where there must surely be a phone.

Marge braced herself and blocked him, screwing the gun into his ribs.

Elgar’s jellied knees liquefied completely. He was looking up at her from the cold, hard tiles of the vestibule floor that had seemed so quaint and friendly on the first visit. But calmly, without surprise, because his life up till now had been one long pratfall anyway.

Behind the lenses, Marge squeezed her eyes together in a vain effort to hold back two enormous tears. Apparently he had failed her by not being a proper loiterer after all. She stood over him, pointing the gun with an accusing quiver.

“My, that’s sure a lot for one little man to own. Now tell me something else. What did you have for breakfast this morning?”

She’d probably never heard of Librium; better not mention it. “A Coke,” he said sheepishly.

“I knew it,” Marge said. “You rich people are all alike. Starvin’. I know all about it. I used to cook for people like you. All them artichokes and anchovies and grape leaves. No nourishment in any of it anywhere.—Fanny Copee, stand out of my way. I got to get this poor little landlord upstairs and inject some nutrition in him.”

While Fanny cried, “Don’t hurt him!” and he pleaded, “I can manage by myself, let me, Mothaw,” Marge got Elgar from behind in a lifesaver’s grip and, using her knees and the barrel of the gun as pistons, propelled him upstairs.

Decorating one of Marge’s kitchen chairs, he felt insubstantial as a pillow loosely stuffed with feathers, for that was how she had treated him, first dumping him there, then plumping him briskly all over to make sure of no broken bones.

In addition to Elgar, the small dark room had other interesting points of decor. Its four walls were a kind of master composition in collage and découpage by a member of the Fauve school. Plastered over every inch of wall space were hundreds of aging magazine pictures, recipes, newspaper clippings, post cards, record covers, sheet music folders, and photographs. Not a space showed between these products of fourteen years of gleeful scissorswork, which were cleverly layered and relayered over each other so that most were tantalizingly only half visible. But he recognized “A Tisket A Tasket” by Ella; John Barrymore and Jackie Robinson in black and white; Pecan Pie and Glazed Ham in full color; Christ’s Agony in the Garden, ditto; “A Guide to Canadian Birds,” rotogravure; and one startling newsprint item that held his attention for some time: “Ten Steps to a Dream Figure.”

She who dreamed of a dream figure waddled through this decorator’s fantasy, ponderous and menacing as a hydrogen bomb, briskly stirring and turning things that bubbled and sizzled and steamed. As she worked she sang, in an incongruously sweet little-girlish voice, accompanied by rhythmic slamming of lids and doors,

I was out all night, my revolver in my hand.

Out all night, my revolver in my hand.

Lookin’ for that woman who ran off with my man.

Finally, with angry emphasis in each plop, she set in front of him:

A bowl of grits,

Four slices of toast,

Six strips of bacon,

A piece of fried ham,

Four fried eggs,

A plate of three-inch biscuits,

A pot of coffee,

And a tureen of cunning little dark sausages frolicking in rich brown gravy.

Oh, he’d pay for this, Elgar thought, swabbing up gravy with a biscuit in each hand, gobbling down three eggs. Most assuredly, most royally he would pay for the crisp sweetness of the fat on this ham. His stomach, tender as the insides of a baby’s thighs, would soon make him groan, and scream, and twist up in knots like a demented pretzel. All that grease. Ugh. Elgar licked his fingers and dipped another biscuit in gravy.

What else could he do, with her standing there waving that weapon at him?

“Eat that other biscuit. Don’t waste it. When my old man said he was tired of my biscuits last week, I knew it was all over with him and me. Next day he was gone.”

Elgar hoped he was not destined to be her next old man.

“Don’t waste that gravy, neither. Sop it all up.”

“I might get sick,” he pleaded.

Fire sparkled behind the rimless bifocals. “Why you puny little thing, you got a nerve. Insulting the first good meal you ever had in your life.”

“Oh, but ish excellens,” he said, and hastily restuffed his mouth.

“Men,” Marge said heavily, and sat down in the chair opposite Elgar. “The more you try and please ’em, the more they mistreat you.

“Fourteen men,” she keened. “Fourteen men in fourteen years. I treated each one a little bit better than the last. And each one left me a little bit sooner.”

It could almost be set to music. It had a lilt and a beat. And the features buried in the swollen dough of her face had once been small and neat and pretty.

“I’m sorry,” Elgar said, and reached out to console her hand.

She jerked it away from him. Her wiry gray hair, bursting its pins and springing loose from its braids, stuck out in angry spikes.

“I’ve had a hard life, mister,” she said as she caressed the butt of the gun. “I’m through trustin’ people, especially people in trousers. You want some molasses?”

He didn’t, but nodded; better not refuse any more of this gunpoint hospitality.

Without taking her eyes from his face, Marge reached out to a shelf behind her, plucked a molasses bottle from it, and slammed it down in front of Elgar. He wondered what he was supposed to do with it: put it on the eggs? the sausages? He also wondered if Marge might be that mythical creature Borden was always describing, the Loving Person. Maybe she just had an angry style of loving.

“Ummm, thank you,” he said noncommittally, and let his eyes wander back to the shelf, hoping to avoid both issues, molasses and men, since he could not win at either.

The curiously assorted contents of the shelf did not make him feel any better. It held a long, black, very dead-looking hairpiece, a human skull and several teeth (her next-to-last old man?), standard bottles of corn oil, vinegar and mustard, and, next to them, some distinctly evil-looking bottles labeled Compelling Oil and Dispelling Oil.

She caught the direction of his gaze and said, “See what men have done to me? For fourteen years I only practiced white arts, mister. Now I practice black arts too.”

Plucking one of the nastier bottles from the shelf, she emptied it into a teacup and began to stir.

“What’s that?” he asked in alarm.

“Clarifying oil,” Marge said somberly. “I read the morning wrong. First time in three years.”

“Don’t worry,” he said, patting her hand gently. “I’m sure it’ll clear up soon.”

This time she let his hand remain. “I read evil visitors on my doorstep today,” she said glumly, and continued stirring. “But you’re too pitiful to be evil. I must have made a mistake. —Ah! Now I see.”

Elgar tried to see something in the murky liquid too, but it was as blank to him as his future appeared right now.

“I’m supposed to protect you from evil,” Marge said. “That’s it. You came my way so’s I could keep you from harm.”

She pushed her chair back from the table, angrily accepting God’s will or Belial’s or whoever’s. “All right. Though I know you’ll repay me with suffering.”

“Oh, don’t say that,” Elgar pleaded. “How can you be sure?”

“Men,” she repeated with tragic emphasis, her fingers curling toward the gun once more.

“One way you might help me,” he suggested feebly. “Since you’re supposed to anyway, I mean. You might, if it doesn’t inconvenience you awfully, put that gun away. Just a suggestion, of course.”

“You the first fool this thing ever fooled,” she said. “It’s old and rusty as me. Never even been loaded. See?”

Aiming just to the left of his ear, she pulled the trigger.

After the explosion, Elgar turned, shuddering, and observed a black smoking hole in Betty Grable’s left knee. Though nothing could tarnish that immortal pin-up smile.

Marge rose sheepishly and put the gun in a drawer.

“Tell me about the other tenants,” he said after a long, long exhale. “What’s this DuBois guy like?”

Marge elevated her nose and sniffed haughtily. “Oh, Professor DuBois don’t bother with the rest of us. He’s a college president.”

“Really?”

“Sure. The college is across town somewhere, he says. —Course I never heard tell before of no college selling degrees for fifty dollars. But it’s supposed to be legal and proper. I guess I’m too ignorant to understand these things.”

Elgar caught himself wondering if the man would sell him a degree. After eight expulsions, the complete Ivy League circuit in four years, even Mothaw had given up. But then, he had given up trying to please her. Didn’t he tell Borden so every day? The hell with college.

“What about the Cumbersons?” he asked. “The couple upstairs.”

“Don’t ask,” Marge said ominously, beginning to stir her cup of oil again.

“Why not?”

“’Cause they been here twenty-five years and nobody’s ever seen them, that’s why.”

“That’s impossible,” he said.

“It would be if they was alive,” she said.

There was silence in the room except for the dainty tinkle of Marge’s spoon in the cup and the rippling of hundreds of tiny, ghostly rodents, dancing behind her varicolored wallpapers and up and down Elgar’s spine.

“Mr. Cumberson was already retired from the railroad when they moved here,” she said. “That was twenty-five years ago. They were both over seventy then.”

“And nobody’s seen them since?”

“Nobody.”

“Well, who pays their rent?” he wanted to know.

“Every Thursday a pension check comes for Mr. Cumberson. I never seen nobody take it out of the mailbox. But every Friday, it’s gone.”

Elgar was indignant. “You’ve been here fourteen years yourself!” he exclaimed. “You must at least have heard noises. In all those years, didn’t you ever get curious, just once, and go up there?”

“I sleep sound,” Marge said, “’cause I got nothin’ on my conscious, and I don’t look into what don’t concern me. Landlord, if you want to go up there, go ahead. All I can say to you is, I got the powers, and I don’t go. ’Cause my powers tell me, ‘Let well enough alone.’ ”

“What kind of powers?” he asked fearfully.

“Oh, nothin’ special. Nothin’ worth botherin’ about. Except, see, any time you got a little something troubling you, tell Miss Marge, and maybe she can fix it. A person robbing you, or crossing you, or spoiling your luck, or some little thing like that.”

“I’ll remember,” he promised. That was motherly kindness glowing at him from behind the rimless glasses. At least he hoped so.

“What are the first-floor tenants like?” he asked. “Copee, isn’t that their name?”

“Oh, Fanny’s a good girl. Just a little ambitious, that’s all. She’s a good mother to those two boys.”

“What about her husband?”

“I don’t believe in speaking evil, Landlord. Besides, I’m concentrating now. If you want, you can go downstairs and meet him yourself.”

She had lit a black candle, and smoke seemed to be curling upward from the cup while she mumbled unintelligible phrases. As the atmosphere was getting distinctly creepy, Elgar decided to follow her suggestion.

But felt not at all the dashing lover as he knocked at fabulous Fanny’s door. Stuffed with sausages and badly shaken. Not the most romantic of conditions.

Worse, he hardly recognized his wild non-Irish rose when she bloomed wanly in the doorway. Face scrubbed, hair skinned back severely, lashes batting more with fear, now, than coquetry. Until now he’d repressed the whole business about husband and children, little-mother role not suiting her, somehow. But from the glorious dragons rampant on scarlet fields she had changed to a mournful, motherly Muu Muu of limp, gray seersucker.

The first-floor apartment was a Dragon Lady’s lair, though: red walls, lowering reddish lamps, gaudy Chinese-type furniture crouched to spring everywhere.

Finger to her lips, Fanny let him in and said, “Shhh. Charlie’s studying his history.”

From the deepest armchair a curl of smoke rose. Pipe, not incense.

“Who goes there, wife?” came a voice from that vicinity. “Friend or foe?”

“Ofay,” she answered, giving Elgar the key to the pig Latin the Enemy was not supposed to understand.

“Then let him wait hat in hand,” came the answer. “As I have waited all day long in his employment lines and his unemployment lines.”

“Now wait a minute,” called Elgar. “I don’t know where you were today, but those weren’t my lines you were in. I don’t have any lines. As it happens, I don’t have a hat, either.”

The chair swiveled. A thick tome was lowered with awful deliberateness to reveal ruddy-brown, warpath features topped by angry, upstanding black hair.

“Who dares to contradict me in my own house? In my castle which he has invaded?”

“As it happens it’s my house,” Elgar replied. “I’m the new landlord.”

“And as it happens this sector of it is my castle. Within which I am king. You are here only on my forbearance.”

“I am here on my business,” Elgar corrected. “Which is to request your wife to remove her commercial advertising sign from my residential window.”

The king rose from his throne to menace Elgar. Unfortunately his height, about five-four, and his bandy legs did not go with the imposing attitude. Elgar judged he could easily take him in a fight if necessary. Which might prove to be the case.

“So,” Charlie intoned, “you would deny this poor woman the livelihood which she must earn to pay your unconstitutional rentals. Oh, I know you, mister. I don’t need to know your name. Whoever you are, you are the exploiter, the Enemy.”

He was beginning a kind of rain dance, hopping around slowly on one foot. Hop, turn, and point a skinny finger at Elgar’s nose.

“What is more,” he accused, “you have probably been coveting my wife and plotting to seduce her behind my back. It is not enough to be an exploiter, you have to be a seducer too. Like others of your breed. Oh, I know your kind.”

“Charlie, please,” Fanny interrupted. “He’s not so bad really.”

“They’re all bad, squaw. See to your papooses. Make sure they are asleep. Some things are about to happen which I do not intend for tender young ears.”

—My howls while he scalps me? Elgar wondered.

Fanny, leaving the room, gave him an eloquent eye-roll and a shrug which seemed to pooh-pooh his fears.

Clearing his throat for courage, Elgar said, “What were you reading when I came in, Mr. Copee?”—expressing, he hoped, the proper amount of polite interest.

The title “Mister” must have helped. Charlie growled almost civilly, “The History of the Choctaw Nation. Are you familiar with it? You should be. Three times your people made my people false promises. Three times you robbed them of their lands and forced them to move. Three times, yet not a hand of my tribe was raised against you.”

He had the effective trick of all successful politicians, Elgar noticed, repetition for emphasis. Three times was the rule. Especially effective when the phrase repeated was also “three times.”

“Bravo, Mr. Copee!” he applauded. “Ever think of going into the speechwriting game? You’ve got a real knack for it. Washington could use you.”

“Laugh while you can!” retorted Charlie. “Your laugh sounds hollow, white man. Your short hour is almost up. You cannot delay vengeance forever. Soon we will ride the plains and reclaim our lands.”

“You don’t look like much of a rider to me,” Elgar said. “Too bent over. You got to get that old back straight as a ramrod.”

Charlie unconsciously corrected his posture, Elgar assisting with a slap on the back.

“Better,” Elgar approved. “More like it. Don’t let the shoulders sag, now.”

“So history repeats itself,” Copee said with bulging eyes. “First you rob me of my land, and then you come onto my reservation and dictate to me.”

“Only about the signs, Chief,” Elgar said. “This is not a commercial reservation.”

“Well, that’s good. Because I’ve just decided to pay no more of your commercial rentals. You stole my ancestors’ lands. By rights you owe me and my descendants three hundred rent-free years.”

“Well, you can’t have them, Chief,” Elgar said, facing up to him, glaring, their noses almost touching in a dangerously intimate powwow. “So you just better get on that horse and ride West. Hit that long dusty trail into the sunset, if you don’t intend to pay rent, or if your wife intends to operate a business here. Either or both. That’s all I came to say. Thank you.”

Copee said, “Our tribe is slow to anger. But you have taken advantage of our patience too long. This time you have gone too far.”

Everybody around here was sensitive to advantage taken, Elgar noted. Must try to avoid giving that impression in future.

“Charlie! No!” shrieked Fanny, back in the room in enchanting deshabille. Elgar barely had time to notice the interesting new item she was wearing, or rather not wearing. He was too busy watching her crazy husband remove something from the cushions of his chair.

A tomahawk. Which he waved over his head as he resumed his rain dance.

“The tribal wrath is aroused!” he chanted. “The ancestors must be appeased! The tyrant must leave the reservation! This is war!”

With a cute little side-arm windup, he suddenly hurled the tomahawk. Just missing Elgar’s head, it dug deeply into the wall, jarring loose a shower of plaster, and hung there trembling.

“I’ll bill you for the plaster job,” Elgar said evenly. But he was moving fast.

Fanny, holding the door open for him with one hand and keeping up a wisp of pink froth with the other, whispered, “You lucky. This ain’t nothin.’ Last month he was a Black Muslim. Next time, come around in the daytime, Landlord.”

Wheezing and puffing, Elgar tore up the street, remembering with shame that nothing had been accomplished yet in the way of measuring windows for weatherstripping. And not one “Paid” entry in any rent book, either. Worse, he felt an attack of gas coming on, and wanted badly to slow down for a burp or two. But seemed to hear moccasined feet slipping and slushing behind him.

“Borden!” he screamed as he whizzed around the corner, “Borden, there will be no cute phone calls tonight, you understand? Cancel all your other patients and prepare to see me in person. Man to man, face to face, Borden. This is war!”