Читать книгу A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits - Laura Cumming, Laura Cumming - Страница 6

1 Secrets

Оглавление‘The world so conceived, though extremely various in the types of things and perspectives it contains, is still centerless. It contains us all, and none of us occupies a metaphysically privileged position. Yet each of us, reflecting on this centerless world, must admit that one very large fact seems to have been omitted from its description: the fact that a particular person in it is himself.’

Thomas Nagel, The View from Nowhere.

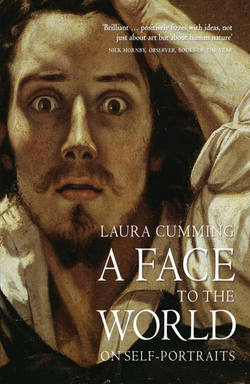

Portrait of a Man (Self Portrait?), 1433 Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441)

On a clear day, when the sunshine is bright, we cannot help glimpsing ourselves as spontaneous reflections, vividly present in polished metal and glass, more provisional in opaque surfaces. The pianist becomes aware of his fingers echoed in the sheen above the keyboard. The caller sees his face in the mobile phone. The writer becomes a shadow in the computer’s screen when the glare gets too harsh, coming between her thoughts and her words as maddeningly as those vitreous flecks that drift across the optical field when staring at a white sky or during the prelude to a migraine; each is an involuntary manifestation of oneself.

At home we only have to draw a curtain to deaden our own image but the wider world is not so conveniently adjusted. We spot ourselves large as life in the windows of shops, tiny in wine glasses and spoons, in others’ eyes and the lenses of their spectacles. Mainly we ignore these inklings of ourselves, except when the object that contains them is big enough to be exploited as a face-checking device, but the truth is that nobody actually needs a mirror to see how they look. The daylight world is a sphere of endless reflections in which we are caught and held, over and again, and even at night the curtainless window becomes a mirror when backed by outer darkness. Surrounded by these shining surfaces and the reflections they give back, there is no getting away from our selves.

Flemish painting loves this world of surfaces. It aims to do them to perfection, as if getting them exactly right was the guarantee of some higher truth than material reality. And this must have seemed the case nearly six hundred years ago when these painters very suddenly began creating images of God’s universe so persuasive to the eye, all the way from the broad rays of the sun to the microcosmic fire inside a diamond, that contemporary viewers thought they could hardly have been made by human hand. A saint’s golden cope and all the tinsel-bright threads running through it; a carpet and all its individual woollen staples, and then every thread in each: surely this must be some kind of God-given miracle, for such minutiae couldn’t possibly be rendered by an ordinary mortal with a paintbrush. The old strain of incredulity rings true even today since one still marvels to see such immaculate illusions of life unfolding from the nearest dewdrop to the furthest range of mountains. And if Flemish art aspires to a visibility that amazes then the work of Jan Van Eyck goes even further, rising to a kind of godly omniscience – all you can see and more, as much of the world as can be gathered into the little compass of a painting, above, below and beyond. Van Eyck developed a way of expanding the field of vision by using reflections to show what was just out of sight as well as what was beyond the picture altogether: the entire skyline of a distant town reflected in the gleaming helmet of an archer, an offstage martyrdom in a heretic’s breastplate. The armour will be super-real, so like the thing itself as to baffle belief; the reflections will make visible even more of the world.

When it comes to reality, Jan Van Eyck is the supreme master. His art is so lifelike it was once thought divine. But he does not simply set life before us as it is – an enduring objection to realism, that it is no more than mindless copying – he adjusts it little by little to inspire awe at the infinite variety of the world and our existence within it, the astonishing fact that it contains not just all this but each of our separate selves. What is more, Van Eyck makes this point in person, and not once but several times with a humility that amounts to a trait. Yet experts barely seem to notice the human aspects of these incidental appearances, or the startling solo portrait he left of himself, for arguing about whether they can be deemed self-portraits in the first place. This is one of the disadvantages of being a pioneer; Van Eyck is too early to assimilate. Because there is no flourishing tradition of self-portraiture in Europe yet, he is not allowed to be painting himself. Clearly there must have been great self-portraitists before him when one considers how much art of the period is lost (some estimate that only a quarter of Renaissance art survives) but even quite serious art historians seem to imagine that nobody could produce a sophisticated self-portrait without a sophisticated mirror, or that nobody had a self before its supposed invention later in the Renaissance and that Van Eyck is only fooling about with figments. But his art argues against such primitive and arrogant notions and does so with characteristic grace. Look at the way that Van Eyck finesses his own image into a great altarpiece such as The Madonna and Child of Canon van der Paele by way of drawing attention to the fact that anyone who looks at a bit of fiercely polished metal, no matter how grey the day, is pretty much bound to see himself.

The Madonna and Child are sitting in a space so cramped there is hardly room for their visitors: St Donatien on the left in a blue and gold cope, St George on the right in a cacophonous suit of bronze armour. George is a bumptious figure, disturbing the peace and treading clumsily on the vestments of the old cleric kneeling beside him, namely Canon van der Paele, who has commissioned the picture and is even now being introduced to the Virgin.

The point of the picture ought to be the relationship between these four large adults but there are so many other pressing attractions. The heavy eye-glasses in the Canon’s hand, the circular ventricles of the windows, the individual design of every single chequerboard tile; above all the stupendous patterned carpet that begins beneath the Virgin, folds its way down the ceremonial steps and stretches right out of the picture as if to meet the viewer’s own feet, a sensation fully underwritten by the staggering depiction of this woven stuff, too thick to make perfect right-angle bends down each step, its weave stiffening here, flattening there, casting the tiniest of shadows within in its own texture: infinitesimal.

Van Eyck seems to have started out as a miniaturist and part of his achievement is to sustain that technique on a larger scale without any loss of effect so that his pictures never disintegrate into smaller catalogues of detail; you can be densely absorbed in that carpet without losing your sense of the circulation of air, the passage of light or the reflections that keep the space flutteringly alive. St George doffs a helmet ribbed like a conch, its volutes reflecting the mother and child over and again; and the entire scene, from the red granite column behind him to the cold Northern light of the window, is repeated in his breastplate and shield. But there is one reflection that has no identifiable source in the picture because the original stands outside it – a tiny figure in a red turban, one arm raised to apply a brushstroke.

Madonna and Child with Canon Georg van der Paele, 1436 Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441)

To describe this self-portrait as modest would be an understatement; it is not even the size of a match. Only in a reproduction fully as large as the painting itself – approximately six feet by four – would anyone be able to see it in context. The hiding place is what gives it away, as well as the pose, for to be reflected in the saint’s angled shield at this size the man in the turban would have to be standing back from the picture, near the centre, approximately where we stand to look. And what did the artist see when he stood there? Not the armour, of course, but the wet oil paint itself in which, working close, he must have been hazily reflected.

Detail of Madonna and Child with Canon Georg van der Paele, 1436 Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441)

The conceit is that the armour he has painted is so sparklingly real Van Eyck can see himself in it, and perhaps there was an actual suit of armour in the workshop, a material object to summon in all its hard glory. But there were no saints and Canon van der Paele clearly never met Mary; the artist is making up his world. There is the fictional scene, the wily old canon sucking up to the mother of God, and there is the miraculous illusion of reality that abets it; between the two, slipped into the surface of the picture, is a reflection of the truth and reality outside it: the painter’s side of the story.

Jan Van Eyck was probably born in 1390, possibly in Maastricht. He worked mainly in Bruges as court painter to Philip, Duke of Burgundy, who sent him on at least two ambassadorial missions by sea, voyages so weather-pitched the ships were forced to dock in England for safety. First he painted Isabella of Spain as a potential bride for the Duke and then he painted Isabella of Portugal; neither portrait survives, but the Portuguese Isabella won the contest.

Philip treasured Van Eyck’s friendship as well as his art, giving him vast bonuses and expensive gifts, becoming godfather to his daughter and supporting his widow. That he prized their conversation is apparent from an outraged letter to some of the painter’s clients who were withholding payments, an insult that the Duke takes personally, declaring he will ‘never find a man equal to [Van Eyck’s] liking, nor so outstanding in his art and science’.1 Not just art but science as well, meaning knowledge of mathematics, optics, astronomy, geometry, all the learning that enriched Van Eyck’s painting and no doubt his table-talk, but possibly something else too: the invention of oil paint itself.

According to Vasari, teller of tall tales, Van Eyck one day took a most painstaking piece of work out into the sunshine to dry. When he returned, the varnish had cracked and the wooden panel was splitting. Infuriated, but being a man who ‘delighted in alchemy’, Van Eyck experimented with numerous concoctions of egg and oil until he hit upon a secret formula of linseed and nut oil, mixed with ground pigment, that was not only heatproof but waterproof too and which brought a beautiful new lustre to his colours. Out of base substances, Van Eyck supposedly transmutes the precious stuff that ‘all the painters of the world had so long desired’.

Oil painting existed before him, of course, but most artists were still working with tempera or gesso, mixing their pigments with egg white or damp plaster, and getting stuck with their quick-drying effects. Oil paint gives depth and luminosity and reflects light from within, layer by translucent layer. Fluid and lingeringly slow to dry, it allows for infinite variations of hue, tone and consistency and the subtlest of blends and transitions. Van Eyck exploited all these properties to the fullest degree as no other painter before him, inventing not so much a technique as an entire tradition of painting.

His own pictures look as if they have never quite dried, their surfaces shining with liquid light like the very substance of which they are made. Had he lived in the late twentieth century, Van Eyck might even have painted a stunning picture of oil paint itself: the texture and gleam of it on the palette, another wonder of the world. And working so intensively with the palette and so close up to the surface of each panel he must have glimpsed himself in the oil – not exactly a face, just an imprecise blur in whatever he was painting. As long as the sun shines, there is no getting away from ourselves.

Does this painted reflection amount to a self-portrait? It is too small to be much of a likeness, this indirect glimpse, and for some its size irresistibly reduces it to a joke. ‘More playful than profound,’2 comments one art historian, with a touch of patronizing indulgence, arguing that the artist does not show himself so much as his character. It is true that one could hardly extrapolate a recognizable likeness from the face and yet something more than character is surely represented in this little self-portrait.

Not at all, according to other experts, for this is not Van Eyck.3 Lay people may want it to be a self-portrait but they only see what they want to see and there is no textual evidence to support the claim. Written evidence trumps visual evidence for art historians even more than for lawyers; without documentary support, such identifications are purely subjective.

Of course, the case could be argued in terms of custom and practice. Artists often appear at the back, in the margins or among the crowds in Renaissance paintings pointing at themselves – it was me, I painted this – and sometimes even gesturing at their painting hand – I made the whole thing with this. (One would have thought the tiny brush in Van Eyck’s hand would have amounted to a form of positive ID too but his case proves more complex.) Some go even further, putting a name to the face. Benozzo Gozzoli included himself among the throng of Medici godfathers and hangers-on wending their way down a valley on horseback in his Procession of the Magi for the Medici chapel in Florence. He wears a scarlet hat with the words ‘Opus Benotti’ lettered in gold round the brim, a pun on his name – Ben Noti, well noted – which was also something of a self-fulfilling prophecy since his is practically the only name not now lost. The caption beneath Pietro Perugino’s pretend ‘portrait’ of himself hanging from its trompe l’oeil chain among the frescos of the Collegio del Cambio in Perugia declares that if the art of painting had never existed then Perugino would have invented it, though since he lavished more care on himself than anyone else – the self-portrait could almost be Flemish – no one could be fooled by this third-person rhetoric. It is traditional to regard such self-portraits as elaborate signatures or advertisements, instances of attention-seeking painters asking to be elevated to some higher status than anonymous craftsmen, though even Gozzoli and Perugino show more conceptual wit than such narrow interpretations allow. But Van Eyck presents problems for experts. Unlike either of the Italians, he did not support this or any other self-portrait with written certification.

So there are supposedly no self-portraits by Jan Van Eyck because none can be substantiated; or there might be one; or they are all just stick-men in a running gag. If Van Eyck paints a reflection of himself in a pearl he is simply celebrating the shininess of the world, not alluding to his own place within it. If he paints a reflection of a man in a turban in The Arnolfini Portrait, it is just another way of signing the work. Right at the outset, the depth and complexity of self-portraiture are already being denied.

But it is not romantic to call these reflections self-portraits; it is a mark of respect. Van Eyck’s art teaches the eye to see the world on an infinitesimally small scale, and it hardly belittles picture or painter to suggest that the miniature figure in the armour expresses self-consciousness in its maker: a figure in the visible world. What wit, moreover, to clinch this extraordinary illusion of reality with a reflection that introduces the here-and-now right into the picture, as if the real and painted worlds were continuous; while at the same time jamming that illusion with a reminder of the artifice involved in the picture’s making personified in the image of its maker. Discount the possibility of a self-portrait and you deny Van Eyck all of these marvellous possibilities. Put simply, you refuse to allow that he could be such an intelligent painter.

Appearances are everything in Van Eyck’s art, and his art is devoted to making them real. Most representational painters leave something to the viewer, requiring us to imagine or deduce some parts of the picture, but Van Eyck does the opposite: his paintings are stupendously complete. Not a hair out of place. Yet it is precisely this fullness of reality that Michelangelo dismissed in an early objection to the realism of the Flemish school: ‘They paint stuffs and masonry, the green grass of the fields, the shadow of trees and rivers and bridges … And all this, though it pleases some persons, is done without reason or art.’

Without reason? Without art? Look at another painting by Van Eyck, in which the Madonna and Child are foolhardy enough to grant an audience to the Duke of Burgundy’s intimidating chancellor. Rolin is a big man with a savage haircut and a look of brute cunning, much like the enforcer he was in real life. The Madonna appears to be drawing cautiously back, but the child on her knee is blessing the politician: exactly what Rolin had paid for.4

Behind the lavish chamber in which they sit a whole world unfolds through the windows: green fields, rivers, the shadows of trees and bridges, a sparkling city and beyond it brighter vistas yet. ‘Even those landscapes which seem to extend over fifty miles retain the same degree of solidity and the same fullness of articulation as the very nearest objects,’ wrote the art historian Erwin Panofsky in a famous passage of praise. ‘Jan’s eye operates as a microscope and a telescope at the same time.’5 And all this reality – the palace garden and every leaf of it, the meadows and every blade of them to the furthermost glittering pinnacles – is paradise on earth, the landscape of the New Jerusalem.

Detail of The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, c.1435 Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441)

Between this world and the next, near and far, two little figures are posted like watchers on a promontory. One is studying the view from the palace battlements, the other turns slightly, glancing back in our direction. He wears a red turban and carries the rod of a courtier. The crucial fact about this figure is once again its position, on the threshold between two worlds, present and future, and right at the epicentre of the painting. Draw the diagonals and they would meet on a point: the hand of the man in the turban.

The angel in the New Jerusalem, according to Revelation, has a rod to measure the glorious architecture of the city. The measurements of Van Eyck’s New Jerusalem are exceptionally small – the whole picture is only about two feet wide – and his rod is thus sensationally tiny, a microscopic yardstick for a miniature vision. But even without the biblical aside, and Van Eyck’s paintings are always theologically rich, the little man in his eye-catching turban has a modest humour all of his own: discreet enough to escape Rolin’s self-centred attentions, you feel, but there for those who have eyes to see him.

Van Eyck places himself at the crosshairs of his own field of vision; painting the world, and all its contents, he numbers himself within it. This is not narcissism but modest logic: even without a mirror, or reflections, we are visible to ourselves somewhat. Shut one eye and the projecting nose becomes apparent; look up and see the overhanging brow. We have an outer as well as an inner sense of our own bodies that reflections confirm or confound; and catching sight of these reflections, we are made episodically conscious of our own bodily existence – atoms in time, maybe, but nonetheless the viewing centre of our world.

It has been argued that the only reason anyone ever imagines these little men in red turbans might be Van Eyck is because of another painting by him known as Man in Red Turban.6 Or at least that was its title until very recently when visual evidence was finally allowed to outweigh academic caution just a fraction and scholars relabelled it Portrait of a Man (Self-Portrait?).7 In fact, there is a faint long-nosed resemblance between this man and the courtier with his rod that has nothing to do with turbans; and turbans are in any case off the point.

Van Eyck stares piercingly out of the picture, a tight-lipped man with fine silver stubble. His look is shrewd, imperturbable, serious. The eyes are a little watery, as if strained by too much close looking, and there is a palpable melancholy to the picture. Look closer, as Van Eyck’s art irresistibly proposes, and you notice something else – that the eyes are not in equal focus. The left eye is painted in perfect register and so clearly that the Northern light from the window glints minutely in the wet of it – the world reflected; but the other is slightly blurred, you might say impressionistic. These eyes are trying to see themselves, have the look of trying to see themselves in some kind of mirror. ‘Jan Van Eyck Made Me’ is written below the image. Along the top runs the inscription ‘Als ich kan’ – ‘As I can’, and punningly ‘As Eyck can’.

Van Eyck painted the ‘Als ich kan’ motto on the frames of other portraits too but it is far more emphatically displayed here to create the illusion that it has been carved into the gilded wood itself. It also appears where he normally names the sitter. But more than that, its play upon the first and third person epitomizes the I-He grammar of self-portraiture to perfection. Here I am, gravely scrutinizing my face in the mirror, and the picture; there he is, the man in the painting.

I am here. He was here. ‘Jan Van Eyck fuit hic’ is written in an exquisite chancery hand on the back wall of The Arnolfini Portrait. Ever since Kilroy was here and everywhere in the twentieth century the phrase has epitomized graffiti, which is, in its elegant way, exactly how Van Eyck uses it.

Everyone knows the Arnolfini – the rich couple with the dog, the oranges, the mirror and the shoes, touching hands in an expensively decorated bedroom. But nobody knows quite what they are doing there, in a bedroom of all places, an intimacy unheard of in Flemish portraiture. This joining of hands, is it the moment of betrothal, the marriage itself, the party afterwards, or nothing to do with a wedding? The bed awaits with its heavy scarlet drapes, the dog hovers, the texture of its fur exquisitely summoned all the way from coarse to whisper-soft. Perhaps he is an emblem of fidelity; perhaps this is a merger between two Italian families trading in luxury goods, as lately suggested, but all interpretations are necessarily reductive for none can fully account for the strange complexities of the painting. Even if one knew precisely why Giovanni Arnolfini was raising his right hand as if to testify he would still be a peculiarly disturbing presence, with his reptilian mask and lashless eyes, dwarfed beneath a cauldron of a hat. He touches, but does not look at the woman. She struggles to hold up the copious yardage of a dress that nobody could possibly walk in. Behind them is that writing on the wall that makes so much of the historic moment, and beneath that is the legendary mirror in which Van Eyck is reflected (in blue), entering into the scene.

Jan Van Eyck was here. It is not strictly accurate in terms of tense, of course, for Van Eyck has to be here right now as he paints his story on the wall. He sends a message to the future about the past, but it is written in the present moment; the paradox is its own little joke, as for every Kilroy. But the mirror also tinkers with the tense of the picture. Without it, you would simply be looking at an image of the past, a time-stopped world of wooden shoes, abundant robes and a sign-language too archaic to decode. But things are still happening in the mirror, a man is on the verge of entering, life continues on our side – the painter’s side – of this room. For Van Eyck invented something else too, not just a new way of painting but the whole idea of an open-ended picture that extends into our world and vice versa. Just as his reflection passes over the threshold to enter the room where the Arnolfini stand, so he creates the illusion that we may accompany him there as well. The tiny self-portrait is the key to the door. Art need not be closed.

Detail of The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434 Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441)

The inscription in The Arnolfini Portrait announces the artist’s role as witness and narrator – I was here, this was the occasion – though the self-portrait says something more about the reality depicted. The liquid highlights in the eyes, the pucker of orange peel, the flecked coat of the dog, the embrasure of clear light, reflected again in the brass-framed mirror: the whole powerfully real illusion was contrived by Jan Van Eyck, transforming what he saw into what you now see here. He is there in the picture connecting our world to theirs, a pioneer breaking down frontiers.

As usual, the painter makes no spectacle of himself. Van Eyck’s self-portraits are conceivably the smallest in art, certainly the most discreet, yet their scale is in inverse ratio to their metaphysical range. The visible world appears to be outside us, viewed through the windows of the eyes, and yet it contains us all.