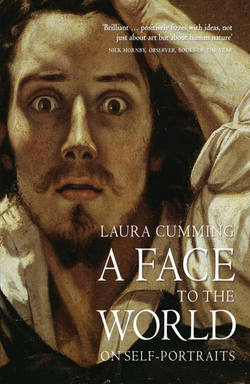

Читать книгу A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits - Laura Cumming, Laura Cumming - Страница 9

4 Motive, Means and Opportunity

Оглавление‘I write not my exploits, but myself and my essence.’

Michel de Montaigne

Detail of The Last Judgement, c. 1538–41 Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564)

At the dead centre of The Last Judgement, within touching distance of Jesus Christ, Michelangelo makes an appearance. He is not on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, where you would have to crane your neck to spot him in the soaring multitude, but right there in plain view above the altar. The artist who has painted the dawn of creation, from the moment God imparts the spark of life to Adam, now appears at the last trump to face God; but all he shows of himself is a ragged epidermis, limp as chamois leather, dangling from the hand of a saint. There and not there, Michelangelo is no more than his own outer casing, displayed as the flayed skin of Bartholomew who was martyred for his faith. And while this Bartholomew is a magnificent creature, muscle-bound, heroic, turning his classical head towards Jesus – exactly as one might imagine Michelangelo, a figure powerful enough to wrestle whole worlds into being – the artist is just an empty overcoat hitched to a rubber mask. Yet Michelangelo was immediately recognizable to his contemporaries, as he is now, even in this exiguous state.

Detail of The Last Judgement, c. 1538–41 Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564)

He is known to have scorned portraiture, especially the scrupulously accurate Northern European variety James Boswell hoped to emulate when depicting Dr Johnson in his biography in ‘the style of the Flemish … exact in every hair, or even every spot on his countenance’. To the Florentine this was just tedious imitation, aspiring to nothing more than the banality of fact. A child of the Italian Renaissance, a student of the classical fragments in the gardens of the Medici villa, Michelangelo believed in the poetry of perfection, the ideal figure, the transcendence of the spirit over the mortal clay. Vasari, who knew him well, even claims that Michelangelo refused to make portraits because ‘he hated drawing any living subject unless it were of exceptional beauty’ and when commissioned to sculpt Lorenzo and Giuliano Medici the artist himself confessed to giving them a grandeur they certainly were not born with. In fact, these effigies in the Medici chapel scarcely look like human beings at all, and when critics descried them as implausible, Michelangelo famously retorted that in a thousand years nobody would know or care what the Medici looked like.

The same is not true of the artist himself, a man who presents such an image of total creative power – the immense scale of his imagination, the sheer force of his labour, from the gigantic block of marble to the sleepless nights and days on the Sistine scaffold, always striving to achieve ever greater figures – that admiration for his art shades into admiration for the imagined man. Long before Charlton Heston bared his biceps in The Agony and the Ecstasy, Michelangelo was already in danger of becoming art’s superman, a cartoon Vasari inspired with his praise of the artist’s prodigious muscle-power. But Michelangelo does not collude with this legend in the Sistine self-portrait, quite the opposite; he presents himself as a man entirely without power.

In his self-portraits, Michelangelo is always more concerned with the inner soul than the outer man. As the model for Nicodemus, helping to bear the body of Christ in a marble Pietà, he sculpts himself with head reverentially bowed and hooded, prayer embodied; as the flayed skin in The Last Judgement, he is not so much portrayed as disembodied. Yet each self-portrait has its distinguishing characteristic that alone might represent him; as Van Gogh has his wounded ear, as Dalí has his moustache, Michelangelo has his broken nose.

It was smashed in a fight with a fellow artist, Pietro Torrigiano, who finally lost his temper, it is said, after years of sharp-tongued provocation. Michelangelo often spoke of his ruined nose – though not the incident – and he alludes to its ugliness more than once in the long sequence of sonnets begun in later life. Of course, it seems to suit his physique, wiry and with a boxer’s build even into old age; but it also fits his temperament, this titan of terribilita who said he took in chisels and hammers with his nurse’s milk. Michelangelo’s nose is his emblem, and it is all he needs to stretch a self-portrait out of the nearly formless Sistine mask.

Michelangelo was in his late sixties when he finished The Last Judgement and much preoccupied by thoughts of dying, death and the resurrection of the body, the end of time and the punishment, or forgiveness, of sins. He often wrote about shrugging off the mortal coil, escaping his ugly and sinful body in hope of spiritual redemption, and in Sonnet 302, appealing to God’s grace, he recalls the sacrifice of Christ on the cross:

You peel of flesh the same souls you apparelled

In flesh; your blood absolves and leaves them clean

Of sin, of human urges, all that is mean.1

The self-portrait epitomizes this longing for absolution, the peeling away of the flesh in order to be reborn. It imagines the exact nature of this out-of-body experience and makes it visible to all. Here is Michelangelo as he once was, a remnant of his former self, spirit flown; and here is how he might be in the full-scale bodily resurrection, more like Bartholomew with his nose intact. For the point about the saint is that he is an ideal figure, a higher being compared to this discarded rag.

How one is to achieve this transfiguration was the great anxiety of Nicodemus, the elderly Pharisee who repented his sins the minute he heard Christ speak. In St John’s Gospel, Nicodemus asks Christ directly ‘how a man can be born again when he is old’, to which Christ gives no answer except that he has to be reborn. Michelangelo asked the same question in a late sonnet: ‘How might I find salvation, with death so near and God so far away?’ Like Nicodemus, uncertain of salvation, he must neither presume nor despair since both are sins against hope. And hope is all; hope and prayer.

The alleged relics of Saint Bartholomew lie beneath the altar of a church only a few miles from the Sistine Chapel, a shrivelled parcel brought to Rome in the tenth century. One imagines them folded like garments. Yet Michelangelo, who had dissected corpses and peeled back the skin to study the anatomy within, would have known that the membrane does not come away like a coat. The flayed skin in The Last Judgement is not remotely realistic, any more than the impossible pose of Adam reaching out that tentative forefinger to God; Michelangelo’s profound understanding of anatomy is not put to the service of knowledge, as with Leonardo, so much as passionate faith. As for the likeness, no Flemish artist would have called it a portrait. Yet this coat has a face, and this face has vestigial animation, the head turning dolefully sideways. It needs to look like Michelangelo, even in this unimaginably debased state, to be part of this vision of bodily resurrection, to personify the artist’s prayer. Michelangelo offers himself up to God not as Dürer has – in His divine image, perfectly beautiful – but as the shucked skin of a repentant sinner.

Nobody seeing this image in the Sistine Chapel could imagine that mere self-depiction was the artist’s object. Michelangelo is there at the last judgement, suspended between heaven and hell, appealing to God for redemption. One might add that the difference between saint and skin is also the opposition between Michelangelo the idealized artist and Michelangelo the broken-nosed mortal, a warhorse who wore the same dog-skin leggings for months on end until his skin came away when he peeled them off, an old man who had no use for his body other than to keep on working for the greater glory of God.

Nor would one imagine that anybody could construe this as simply a signature, and yet that is the received tradition of art history. Self-portraiture starts in the margins as a way of signalling authorship – painters should be seen as painters, not just anonymous craftsmen – and develops as a way of promoting one’s art in person. It becomes more prevalent with better mirrors, better paints, a bigger clientele, more competition and thus a greater need to promote oneself. Before self-portraits eventually break free of the crowd, becoming the image of I, myself and me alone, artists are generally there as witnesses – the self-portrait in assistenza – which is really a cover for signing the painting with one’s image. Histories of self-portraiture tell this originating myth over and again, beginning with Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel in 1425, his eyes on Christ (a giveaway), and ending a century or so later with Raphael chatting to Ptolemy and Zoroaster (another giveaway) in the School of Athens, as if these artists had no larger concerns than self-promotion. In between, of course, there is the troublesome precedent of Albrecht Dürer; but he is just freakishly early.

Whether Dürer was the first artist to paint an autonomous self-portrait can hardly be said for sure since so few works of art from this period survive. The tenacious idea that people never painted themselves alone before the Renaissance, or with any degree of self-consciousness, is in any case rather like the idea that people had no selves to paint, that a sense of self was something that had yet to be invented. This idea was promoted early on by the founding father of art history, Jacob Burckhardt. But Burckhardt’s vision of the Renaissance as the moment when the fully rounded modern self finally steps free of medieval mass-uniformity is challenged even by paintings themselves: lost masterpieces such as the legendary self-portrait of Apelles, famed as the greatest artist of Ancient Greece, or Van Eyck’s grave self-portrait in which he seems to be contemplating both himself and death. Conversely, the artist’s face among the crowd never really disappears; all self-portrait traditions come round again in perpetuity. Frans Hals is there among the Amsterdam burghers in the seventeenth century. Velázquez appears in The Victory of Breda. Edouard Manet listens pensively among the milling figures in Music in the Tuileries. The British sculptor Marc Quinn’s rubber cast of his own skin, still bearing his features, hangs upside down from a hook, flapping open like a skinned banana but completely empty as if Houdini had flown (its title is No Visible Means of Escape). Quinn is always trying to free the spirit in his self-portraits, like Michelangelo half a millennium earlier.

Even where conventions develop – the artist as witness, as religious adherent, as professional painter – self-portraits often have far more complex origins and motives. They are made as love letters, appeals for clemency, campaigns against specific people or the art world in general. They are made in revolt against one’s patron or to exorcize one’s demons, like Franz Xaver Messerschmidt with his stricken, gasping, grimacing bronze heads made to see off the Spirit of Symmetry. Sometimes they are made out of madness or fury.

Detail of St Benedict’s First Miracle, 1502 Giovanni Bazzi (‘Il Sodoma’) (1477–1549)

When the monks of Monte Oliveto hired Sodoma to paint a fresco of the first miracle of Benedict, their patron saint, he arrived with a menagerie of horses, dogs, guinea pigs, badgers, swans and a raven he had taught to shout amusing insults when people knocked at the door. Sodoma insisted they all be stabled, and then demanded numerous items of clothing for himself and his assistants – Florentine stockings, new shoes, even the ostentatious yellow cloak of a Milanese nobleman who had come to take orders. The monks kept a written account of the visit in which they refer to the artist as ‘Il Mattaccio’, the buffoon. He did not leave for three years.

Sodoma was supposed to be painting the boy Benedict successfully praying that his nurse’s broken tray will be mended by divine intervention, and sure enough you see the tray and Benedict praying on the left, and then receiving congratulations on the right. But bang in the centre, far larger than anyone else, dressed in the Milanese cloak and the Florentine hose, is the artist. Around him flock the badgers, swans and raven, as if he were St Francis of Assisi. Way in the distance hangs the mended tray, to which Sodoma gestures – here, take a look at this! – as if he had performed the miracle himself.

It is impossible to view the painting without being completely distracted by Sodoma. He is not there because he believes, like Botticelli. He is not there as a witness so much as the main protagonist. This is simply an insane folly that the monks never managed to prevent, if they ever tried, worn down by his obstreperous presence.

One assumes piety in Renaissance artists because the alternative seems too heretical for the times, just as one assumes that any artist of any era appearing in a Bible scene must be on the side of right. But Caravaggio, in his early self-portraits, is among the dramatis personae of some very violent biblical incidents in which he is no simple onlooker, nor even on the side of virtue; never entirely innocent, he is always in some measure complicit.

Caravaggio is there, for instance, in The Taking of Christ in which Jesus is being arrested with appalling force in the garden of Gethsemane the night before Good Friday. The sense of motion, of figures gesturing and twisting in the darkness, is vividly proleptic, as if they might burst right out of the canvas. Christ is the only still figure, hands calmly clasped in the brutal onslaught, withstanding the terrible right to left motion as Judas and a rush of soldiers in jet black steel close in as if for the kill. Violent, crowded and tight, the event is caught in a flash-bulb glare – and at the far right is Caravaggio himself, holding up a lantern to illuminate both scene and picture.

Caravaggio has made it visible, brought this vision of Christ’s courage and suffering into the light. But the lamp is not some trite symbol, any more than the self-portrait is a signature.

The Taking of Christ is not just a revelation, it has the character of a revelation, of darkness suddenly vanquished by light. Caravaggio shows us the scene and his face in profile, craning to see over the heads of the soldiers, bearing the same expression of open-mouthed awe we all might wear before this violent kidnap. He is on the very outskirts of the picture, struggling to see and make the gospel story visible, this artist evangelist. But his light also aids the soldiers he appears to accompany. Is he not in some sense their accomplice?

‘Pinching himself from time to time, Messerschmidt would cut a terrifying grimace, scrutinise his face in the mirror, sculpt and after an interval of about half a minute repeat his grimace… He seemed afraid of these heads and admitted that they represented the Spirit of Proportion. The spirit had pinched him and he had pinched back… at last, the defeated spirit had left him.’2

Some people have seen mutiny in this self-portrait, a sort of take-me-as-I-am retort to a patron who may have been trying to control the contents of the image. Certainly, almost half of Caravaggio’s paintings were regarded as too independent for the Church. But even if it started this way, which seems a limited motivation – my vision as I have conceived and shown it – this self-portrait is profoundly uninterested in drawing attention to Caravaggio. It is a work of spiritual empathy; Caravaggio enters into the scene in every way.

Why do artists paint self-portraits? It is not a question prompted by portraits. One does not stand before images of monarchs, philosophers, aristocrats or popes trying to guess why they were immortalized in paint. The ruffed courtier, the periwigged anatomist, the uniformed soldier: their place in history, complete with details of occupation and status, and a discreet essay on personality, is pictorially assured. Even if the entire lives of anonymous sitters are lost, one thing is known about them: that somebody wanted their portrait; somebody paid an artist, or perhaps the artist himself wanted to record their image. But even this last possibility does not necessarily hold true in the case of self-portraiture, for many artists have dragged forth a likeness only under duress; at least one was painfully extracted in the mistaken assumption that it was required (see Chapter 12) and many more have been created, then rejected, in a state of heightened disgust.

The Taking of Christ, c. 1602 Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1574–1610)

Some are made with nobody in mind, others for anyone or everyone. A select group was commissioned (and continues to be commissioned) for a very particular audience, namely visitors to the Uffizi self-portrait collection in Florence. This began as the private gallery of Cardinal Leopoldo Medici, who had become obsessed with images that embodied both artist and style. He started with Guercino in 1664 and amassed a hundred more, past and present, before his death. Now there are over a thousand including works by Titian, Rembrandt and (questionably) Velázquez, and the Uffizi has had to ban unsolicited donations from those ambitious to join the club.

Anyone managing to get an appointment to visit the Vasari corridor where a portion of the collection is displayed will see that Leopoldo did not always get much return on his interest in style. An early etching of the collection, hung three deep floor to ceiling, shows what is still apparent today: that it contains some of the dullest self-portraits ever made. Head and shoulders, facing the same direction, many are not much more than variations on a passport photograph. Formal to a fault, but rigorously avoiding anything personal, they end up in opposition to everything that makes self-portraiture interesting: no sense of self, or negotiation between the self and the world, no implied milieu, no distinctive stance, gesture, expression, intellectual or conceptual ideas, just a conformity to type. Of course, there are tremendous exceptions, many discussed here, and the sense of collegiality is strong and affecting. But the official honour appears to have crushed the independent spirit.

Self-portraits do have other coarse and uncomplicated functions. Sir David Wilkie, in a rush to complete his enormous tavern scene The Blind Fiddler, inserted his own face in the wig and mobcap of a tipsy woman as if it were no more than a handy set of asexual features. Francis Bacon said he painted himself only because ‘everyone else was dying off like flies’,3 although the idea that artists make images of themselves faute de mieux, being so compelled to paint a face that even their own will do, strikes a false note when one considers that the struggle to describe oneself is hardly a casual experience. Even Picasso, superfluent draughtsman, complained that he could never catch the look of himself on paper and would have to cut a hole in a canvas and put a mirror behind it in any case just to glimpse what he really looked like.

When an artist wants to join the great art club of tradition, the ambition can be outrageously flagrant. Sir Anthony Van Dyck reprised Raphael’s double portrait with friend; Rembrandt painted himself in the distinctive poses of Peter Paul Rubens and Titian; Otto Dix went right back to the purity of Hans Holbein, drumming home his claim to German cultural inheritance. James Whistler tried to paint himself in the pose of Velázquez’s Pablo de Valladolid and spent the last three years of his life intermittently trying to raise some trace of the Spaniard’s spirit in this ghostly failure of a seance. Even the smallest anthology of artists showing off royal gold chains would include Titian, never seen without Emperor Charles V’s special gift, Rembrandt, who probably had to buy his own, and above all Van Dyck’s Self-Portrait with Sunflower. Made when he was court painter to Charles I of England, this startling image is nothing less than an awards ceremony: Van Dyck, in scarlet satin, turns his head our way while lifting his important chain with one hand and pointing at the outsize flower with the other. The triangulation of hands, eyes and flower joins the dots – I got this royal gold for that painted gold – though the symbolism of the sunflower was enigmatic even in the seventeenth century. Did it imply art or nature or the sunshine of the king’s favour, this dark oval crowned with golden petals turning its face upon the artist?

The picture is a glowing self-appraisal, but like so many of Van Dyck’s portraits that smooth away the flaws and bestow ineffable glamour on the English court, the artist cannot seem to stop himself from undermining the perfection with contradictory details. What tells against all this glory is the tendril of damp hair clinging to Van Dyck’s slightly clammy brow; the artist would be dead at forty-two, it was said, of overwork.

Self-Portrait with Sunflower is a public performance, a star turn. It implies and requires an audience. The triangulation within it projects directly outwards too: Van Dyck looks at us, we look at the sun-king, who in turn gazes upon his favoured painter. It is a picture that calls for applause.

But it is not congenial; it is not, so to speak, on our side. Even the most out-turned of self-portraits, those that invite a two-way encounter, or where the artist is explicitly appearing by popular demand, are not necessarily sociable. Some artists want to appear in public, and tell you so in their self-portraits, others have been forced to do it and show it in defensive recoil.

Compare two paintings made a few years apart. We know precisely why Nicolas Poussin portrayed himself for his motives are laid out in an irritable letter; about the origins of Judith Leyster’s self-portrait we know nothing except what the painting reveals. In fact, so little is known about Leyster that for centuries her paintings were attributed to Frans Hals, whose fame obscured her reputation quite literally in the case of a picture that was found to have her monogram (JL entwined with a star, punning on her surname, which means lodestar) hidden beneath his forged signature. Leyster’s existence might eventually have been forgotten but for this buoyant picture.

Self-Portrait with Sunflower, c. 1633 Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Intimacy is its trick: she was just working in her studio when you walked in, whereupon she pulled up a seat for you too. Cropped like an informal photo, just below the waist and so tight that one elbow and part of the collar do not make it into the frame, she leans casually back with a conversational smile, off duty for a sociable moment.

Leyster smiles, the work-in-progress implies, because she is the kind of artist who paints merry fiddlers, and perhaps because she is fond a joke. She is not trying to downplay her art, in which she takes evident pride, so much as play up its levity. The neat positioning of the two heads, inclined in different directions but both looking at you, embraces you in the mutual warmth of the circle. Like Walt Disney side by side with his animated Mickey, Leyster gestures lightly at the fiddler with the tip of her brush inviting you too to smile at the antics of the little fellow sawing away with his bow. You could not have a warmer welcome.

Poussin, by contrast, distances himself from the task. He sits back from the picture plane, enclosed by his own paintings – the three behind him, the one before him – in an attitude of fastidious withdrawal. He has only agreed to paint a likeness of himself because nobody else in Rome is up to the task, and only to satisfy a friend. ‘I should not have undertaken anything like this for any other living man,’ he informed his old friend Paul Chantelou, who hardly needed to be told since he had years of difficulty persuading him to paint the picture in the first place.

Self-Portrait, c. 1630 Judith Leyster (1609–60)

Poussin is sequestered in gloom, black hair, black cloth draped over his shoulder like funeral weeds swathing a coffin, black diamond glittering in his ring. His shadow falls ominously across the Latin inscription on the canvas behind him: an effigy of Nicolas Poussin from Les Andelys at the age of 56 in the year of the Roman Jubilee in 1650. It reads like an epitaph, proclaiming his affiliation with classical Rome in an austere third person as if someone else was speaking. The painting is resonant with solemn music.

Yet it is not the mood, or even the strange composition of the picture with its quadratic forms and its mysterious air of deliberation and finality, that strikes some commentators so much as the trail of visual ‘clues’ waiting to be deciphered. His toga: a Masonic robe? The four-sided pyramid of his diamond: an emblem of Freemasonry, or a symbol of Stoicism (constant as a rock)? The eye on the diadem worn by the woman in the canvas behind him: the Eye of All-Seeing Vigilance that represents the Supreme Being to Freemasons? Why, the picture was practically painted for Dan Brown to decode.

That this woman represents friendship or art, as prescribed in iconographic dictionaries of the period, seems a good deal more feasible and makes sense given that the picture was a gift for a friend. But the character of the picture would hardly be altered even if she turned out to be All-Seeing Vigilance; it is her positioning in the composition – as much deliberated as every other element – that matters. She looks the other way from Poussin, her animation balanced by his absolute composure, just as his hand rests motionless upon the book while the golden frames of the paintings shoot back and forth like trains rushing in different directions behind the stationed gravity of his head.

Self-Portrait, c. 1650 Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665)

For Poussin these paintings, whatever they show, are his life. By the time he finished this self-portrait in his mid-fifties he had a reputation across Europe as one of the most intellectual and disciplined of masters. He had left France more than twenty years before, despising French painters as strapazzoni, glib hacks who ‘make a sport of turning out a picture in 24 hours’. Truth could only be distilled from intense and protracted cogitation. Compositions had to be tested over and again in advance, rehearsed with wax forms in a toy theatre. Even the most violent action in his work is marked by stasis and meditation. His paintings require you to stop and think, learn, mark and inwardly digest their mysterious dramas, and so it is with this self-portrait – a summation of his art as well as himself, neither offering instant disclosure.

These paintings spread like a hand of cards behind him – an allegory, a blank canvas, the back of a canvas – are all easel pictures. Being an artist in Rome at that time still meant producing frescos, panel-paintings and altarpieces to order, their subject matter generally dictated by the patron. But for Poussin it meant only one thing, easel paintings on landscape-shaped canvases, stretched, framed and painted exactly like the ones in this picture. His landscape-narratives, moreover, and his great religious paintings were never some compromise with a patron. Poussin, considered to have had a stern and melancholy temperament, prone to irritation and loathing constraint, avoided all the usual professional conventions to the point of bypassing the market altogether. He worked only for patrons who had become friends. That he sits in a booth of his own paintings feels majestically apt for an artist whose sense of freedom depended on making art for himself. He would not have painted himself ‘for any other living man’ and he never painted any other living person.

The public reputation encloses the painter, and the painter’s passionate sense of vocation dominates the picture, a passion that has its ultimate testimony in his face. Poussin appears worn out, hypertense, his eyes red-rimmed with the effort of achieving such a high degree of probity. And yet the expression pulls in another direction too, from this fierce look of honour and discipline to something that looks surprisingly like sorrow. It is often said that Poussin was two different artists, that the younger Poussin was a proto-romantic whose pictures were charged with all sorts of conflicting and dangerous emotions, a man who could draw himself tousled and scowling in the early years in Rome, the kind of man who could be arrested during a street brawl like Caravaggio. This artist cools and contracts into the later Poussin, strict classicist and mythologizer whose paintings are above easy pleasures. Perhaps Poussin has moved from intensity to profundity, but something of the younger man’s strength of emotion is alive in the older man’s face.

Deep-seated within the picture, Poussin avoids social contact. He makes an appearance, as all self-portraitists must, with a marked sense of withdrawal. But this refusal to draw close, to be on our side, is elevated to the level of pictorial principle.

Self-portraits raise the question of their own existence but also of our common mortality. Michelangelo appears as the skin of a corpse, alluding to his disappearance from this world (a self-portrait that might alert one to the pathos and humility of his work instead of the usual narrative of power). Goya painted the doctor who saved him from death raising a cup to his lips, supporting his body as in a pietà. The artist’s gratitude is repeated in words beneath; without Dr Arrieta, extinction. Murillo also explained the purpose of his self-portrait with an inscription that is unusually prominent, scrolling out of the bottom of the picture like a document from a fax and transmitting its message just as effectively: ‘Bartolomé Murillo portraying himself to fulfil the wishes and prayers of his children.’

Murillo was the leading Sevillian artist of the seventeenth century, more successful even than Velázquez; after his death, the government had to enforce an export ban simply to stop the last remaining Murillos flooding out of the country. Although he was Spain’s foremost religious painter, he was even more celebrated abroad for his images of street urchins. Children were his subject and his passion; orphaned at the age of eleven and brought up by one of his sisters, he had twelve children of his own. When his wife died, he remained a widower, raising the entire family by himself. Cholera and typhus orphaned many of the models depicted in his pictures and he lost several children during the worst of the epidemics. The words beneath his self-portrait are not empty but a tender expression of paternal love for his surviving offspring, tinged with deep knowledge of mortality.

Murillo is specially dressed to appear after his death in a fine lace collar and black silk tunic (he was, by all accounts, generally more threadbare). Although the highest paid artist in Seville, he gave most of his money to charity and regularly worked for the church without pay; the strain of labour registers in his face. He appears in an oval frame propped on a shelf; perhaps it is a mirror – there is that silvery play of light across the face – or perhaps it is a painting. Either way, it is modelled on contemporary frontispieces representing pictures within paintings.

Self-Portrait, c. 1670–73 Bartolome Esteban Murillo (c. 1617–82)

But the illusion is broken, literally and metaphorically, by the artist’s own hand which reaches out to rest casually upon the frame, signalling subtly towards the palette and brushes on the right, balanced on the left by a drawing – what else? – of a child. Between the tools he used to make art, and the art that supported Murillo’s family, are the words he wrote for his children; the chain of creation is complete. The inscription is poignant but so is the gesture, for in that breach of illusion where Murillo’s hand moves between the two pictures there is a brief sense of freedom, a quickening, as if he were still living.