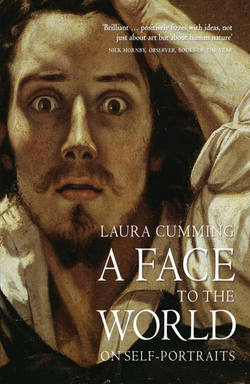

Читать книгу A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits - Laura Cumming, Laura Cumming - Страница 8

3 Dürer

Оглавление‘You make us to thyself and our hearts are restless until we find rest in thee.’

St Augustine

Self-Portrait, 1500 Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

One winter’s day in 1905, a museum guard was meandering through the galleries of the Alte Pinakotech in Munich when he noticed that one of the paintings had changed since the last time he looked. The eyes of Albrecht Dürer’s self-portrait, the most famous eyes in the museum – the most famous eyes in German art – had somehow lost their piercing charisma. The right eye appeared dim and the liveliness of the left severely diminished, as if they could no longer see, and when the painting was taken down, ferocious little rips were discovered in the irises and pupils that had most likely been made, it was agreed, with the tip of a hatpin. The man – or woman – who assaulted the painting may well have used such a weapon, swift, efficient and very conveniently produced and concealed, for it appears that nobody noticed the attack. Somebody unseen, somebody who was never caught, had tried to put out Dürer’s eyes.

Dürer’s eyes – this is how we put it, not bothering to distinguish between the painter and his self-portrait; and we do the same with portraits too. Mona Lisa is what we call both the picture and the young lady from Milan who sat for Leonardo da Vinci. But it feels more natural with self-portraits since artist and sitter are one and the same, being in some profound sense related, image to person. And in the case of Dürer’s 1500 self-portrait, as never before in the history of art, the one would become the counterpart of the other in unique and mysterious ways.

The impact of this painting cannot be overstated: so immediate and yet so remote. At a distance it seems to transmit an unearthly glow that draws viewers across the gallery, and the power intensifies the nearer one gets, not least because the picture is such an unqualified close-up. Dürer presents himself front on, waist up, formidably fixed, immediate and erect. One of his hands is just out of view, as if under the counter, the other fingers the tufts of his fur lapel in a curious gesture that draws attention to both the garment and the wearer, so present and correct, this man who is representing himself. His long moustache is waxed in two scimitar curves that echo the fine arcs of his eyebrows. The hair streams down over his shoulders, a triangle of metal-bright locks, not a single tendril out of place. The face is closed and eerily symmetric. Above all, the eyes transfix.

Even if you knew nothing about German society in 1500, or this period in art, you could assume that Dürer’s contemporaries were amazed by this self-portrait because it still astonishes today. No gold is used in the paint, apart from the inscription, and yet the picture has this peculiar golden radiance. The face appears exceptionally precise and distinctive – strong nose, more of a limb than a feature; slight cast in the eyes; blemish on the left cheek – yet the evidence, for all its heightened clarity, is bizarrely impersonal. What colour are those pale eyes? How old is this person? What is the expression in his look, so pertinacious and yet so withheld? The picture seems both immeasurably more than – and yet strangely unlike – other self-portraits.

It is a double take so improbable one hardly believes it at first. The long hair, centre-parted, the beard and moustache, the gesture of the fingers, the symmetry and stillness and remoteness of countenance, out of time and out of this world: the resemblance startles, incredulity immediately sets in and yet the thought builds like a quake. Is it just chance, a coincidence of fate, or could this man actually have meant to make himself look like Jesus?

People attack portraits when they no longer see, or want to see, them as pictures so much as surrogates or even real people. This is especially true of statues, which are abused exactly as if they were alive, their noses broken, their genitals mutilated, heads and hands brutally severed. Painted people ought to be less vulnerable, safe indoors and protected by guards, but they are victimized too and the connection between people and pictures is held to be so much closer that unlike statues – sightless objects, things apart – we commonly class them together. Nobody would dream of correcting a child who points to a baby in a book, and calls it a baby instead of a picture, and the same is true of our portraits. Even grown-ups plant kisses on images, carry them like champions through the streets, worship them, savage them out of spite or fury, become excited by them as we are excited by people in reality. What is so singular about Dürer’s image, in this respect as in so many others, is not that it has been adored or loathed but that it has excited both extremes of passion and to a greater degree than any other portrait.

This old painting of a man with prodigious hair and alarming eyes has been kissed and excoriated, worshipped and attacked, carried through the streets and mounted on an altar like an icon. It has been accused of self-love and sacrilege and shocking froideur, in spite of which, or perhaps because of which, women have loved it like a man. The German writer Bettina von Arnim became so infatuated with it – or him – that she had a copy made, one she would send to Goethe, for whom she also felt unrequited love, on the curious grounds that it was so precious to her that she might as well be sending herself.1 But was von Arnim in love with the portrait, or the man, or the idea of an artist who could create such an image? The idea that image, man and artist might somehow be one and the same, a trinity, may well be the most potent claim of self-portraiture.

In any case indifference is not what Dürer’s painting invites or inspires, and this sense of agency is crucial to its power; for all its preternatural stillness, the self-portrait feels almost oppressively vital. Just as things seen in a dream may seem clearer than those in the waking world, so one imagines that this self-portrait might have appeared more vivid than the real man himself, and perhaps the attacker felt this vitality was focused in the eyes. The damage to the self-portrait was clinically specific: just the irises and pupils, not the whites or any other part of the face, as if whoever tried to blind him could not stand the drilling fixity of Dürer’s gaze.

Mercifully the rips did not penetrate the Renaissance varnish and the painting was successfully repaired, except for a minuscule spot of dullness in one of the eyes that is invisible to our own but was fastidiously noted in the museum records. It is here that the details of the crime have been buried for almost a century. Museums do not often acknowledge – are perhaps even embarrassed by – the power of art to entrance, frighten or enrage and any viewer affected to the point of violence is inevitably described as insane. So it was with the unknown assailant at the Alte Pinakotech, who is described as categorically mad in the records. This may have been the case; the paranoid and delusional often believe that paintings are staring at them. But among the dry reports of each minute abrasion, the experts cannot help wondering whether the painting itself supplied motive. Why was the painting attacked? Because of the way it looked at its attacker, of course, a person presumed to have ‘taken exception to Dürer’s penetrating stare’.2 It is not beyond belief, even among those who make strong professional distinctions between art and life, that someone – anyone – might experience the eyes as a personal affront. But it is also possible that the attacker may have taken exception to more than the artist’s stare.

All self-portraits are prefaces of a sort. Just as our faces in some sense introduce us, so these painted faces are perceived – and treated – as the prefaces to artistic utterance. They are reproduced on the covers of autobiographies, monographs and fictional lives. They are displayed at the beginning of the museum retrospective like the host at the party, and sometimes at the end in farewell (in which respect, they are once again being construed as surrogates).

In any case indifference is not what Dürer’s painting invites or inspires, and this sense of agency is crucial to its power; for all its preternatural stillness, the self-portrait feels almost oppressively vital.

The self-portrait is cast as a frontispiece, a prologue before we get down to the real work, no matter that it may be among the artist’s greatest achievements, and this Dürer both courts and defies. He puts his self-portrait forward very consciously as a frontispiece but also as an unprecedented work of art. You are not to think that this is just any old painting of him so much as the defining image of Dürer the man and artist.

That he looks like Christ, that the painting resembles a frontispiece: this much is apparent all at once, but neither observation can quite explain the surpassing strangeness of the image. Strangeness is its first and last note. While there are other masterpieces of which this could be said very few of them are portraits, and still less self-portraits, which commonly have as part of their content the artist’s manifest desire to be the very opposite of strange: in fact, to be quite clearly understood.

The figure occupies a peculiar middle ground somewhere between two and three dimensions. There is no backdrop, but no foreground either and no obvious source of light. In fact, the tawny glow that illuminates the scene, beginning at the crown and rippling down through the hair, appears to emanate from Dürer’s own body. This hair, with its unnatural sheen, spreads in triangular curtains from the top of the head to the exact edge of the frame, perfectly contained as if made to measure; and the inscriptions on either side make an opposing triangle, its base the pointing finger below. These inscriptions – Dürer’s famous AD logo and the date 1500 on the left; the details of name and place on the right – are not written on any depicted surface but that of the picture itself, as part of its symmetrical composition; pendant as the scales of justice, they weigh Dürer’s face in the balance. Nothing is allowed to detract from this sense of order, geometry and design, of very close and insistent frontality. All is congruent. The artist is perfectly fused with his picture.

Dürer does not turn, he does not move, he is not looking out at you from any given time or place. He is simply and starkly himself – self-portraiture at its least equivocal – and yet he is also somebody else.

It is not quite accurate to say that Dürer looks like Jesus so much as an icon of Jesus, since nobody knows what the most famous man in history actually looked like. This is an obvious advantage for anyone who wants to slip his own features into the picture, but what kind of artist would do such a thing? It scarcely seems possible that Dürer could propose anything so flagrant and one cannot help thinking, faced with what appears to be an act of astounding hubris, that there are no other self-portraits like it. No other artist of the period represented himself in the image of Christ, and it has not exactly become a convention in the meanwhile. Egon Schiele’s self-portraits, naked, agonized and arms out-flung, could be construed as metaphorical crucifixions lacking only the wooden cross. Paul Gauguin’s comparisons of himself with Jesus – two martyrs united in suffering – are not so much messianic as ironic in their abundant self-pity. Surely the comparison of oneself with Christ would have been considered sacrilegious in its day (if not now) or at the very least maniacally boastful? So the lay viewer might think. But there is no evidence that the painting shocked Dürer’s contemporaries, despite the fact that they were late medieval Christians.

This fact, however, has troubled modern scholars. Ever since German art historians began to devote decades of their lives to Dürer in the late nineteenth century, the question of what he meant and how he was understood in his day has dogged our interpretation of the painting. If there is no evidence of outrage, then the iconography of the self-portrait must have been seen as (or must now be made to seem) completely unexceptional.

Dürer was not a Protestant; it would be another seventeen years before Martin Luther nailed his ninety-five theses to the church door in Wittenberg. Nor, despite his famously bantering correspondence with the humanist Willibald Pirckheimer, his close friend in Nuremberg, can anyone say for certain whether the artist was even a humanist. Historians have gone to great lengths to work up theological justifications for Dürer’s conceit, each opposed to the next. Dürer represents himself as Christ because he is trying to live up to Christ in life as well as art (Imitatio Christi). Dürer takes literally the idea that man is made in God’s image. Dürer sees the human form as an expression of the divine (consider the perfect proportions of the self-portrait) and therefore as a different kind of Imago Dei. It is possible that the painting represents all these possibilities and more, but what is striking about these interpretations, each a counterblast to the last, is the way they neutralize the actual painting. By the time it has been exhaustively theorized, Dürer’s self-portrait has been made to seem not only simple but really quite orthodox and straightforward – precisely what it is not.

Nobody knows whether Dürer’s contemporaries were vexed by the picture. We do not know why he made it, how many people saw it or where it was hung during his lifetime. No such thing as art criticism existed. As Dürer’s great exponent, Joseph Leo Koerner, has written, ‘the entire body of literature about any specific painting of the 16th century in Northern Europe as written at the time can be fitted on one sheet of paper’.3

We do know that Dürer exchanged works of art with Raphael and that his gift to the Italian was no simple depiction but an extraordinary mock-up of the Veil of Veronica. Dürer had painted Christ’s face in gouache on transparent cambric so that it looked the same from both sides and appeared to float in thin air when held up to the light. Christ’s features were those of Dürer.

Since this fabled item disappeared long ago there is no way of gauging how shocking it might have seemed. But it clearly played on the idea of the vera icon as a sort of supernatural self-portrait, Christ’s image mysteriously transmitted without human hand on to Veronica’s veil as he wiped his brow. No human hand; the brushstrokes in the 1500 self-portrait are almost indiscernible.

The painting, with its power of looking, its hieratic solemnity and remoteness, so alien in its lack of intimacy or ingratiation, was evidently made to look like an icon – and yet it is emphatically one man’s portrait. The figure may aspire to imitate Christ, or to resemble icons of Christ, but the inscription pulls hard in a secular direction. ‘I Albrecht Dürer of Nuremberg painted myself with everlasting colours in my twenty-eighth year.’ Nobody is to be in any doubt about which mortal painted the picture, or that it is a self-portrait – as against an icon – resolutely made to last for ever. The more one contemplates this painting, the first proleptic leap in self-portraiture, so cunningly conceived as a double identity, the more it seems to be poised in perfect tension between icon and portrait.

Albrecht Dürer was first in so many ways. Born in Nuremberg in 1471, he was the first great sightseer in European painting, making the hazardous crossing of the Alps more than once, living in Venice, travelling back through Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. He once voyaged for six days on a small boat in the middle of winter in search of a whale that had washed up on a beach in Zeeland. Like his contemporaries he was fascinated by marvels and his journals are full of astonishing sights – a great bed in Brussels sleeping fifty men; soaring comets; Siamese twins; the bones of an 18-foot giant. And whatever Dürer saw, he drew: a ferocious walrus, a dragonfly landing awkwardly on the ground, even what appeared to him in dreams; the face of Christ as it came to him one feverish night, a hellish deluge flooding a plain. Dürer was the first to paint a landscape purely for its own sake and to make the sights he saw available to the world in the form of mass-produced prints, a medium in which he is the true pioneer and the first genuinely international artist.

It may be anachronistic to say that Dürer was the first to use his own image as a brand – others did this for him, issuing his self-portraits in the form of prints and medals even while he was alive – but he does seem to have felt as no artist before him the value of putting a face to one’s name. How easily reputations could be forgotten must have been clear to him in his native city where he was surrounded by the masterworks of artists whose names were unknown, their histories forgotten, in the city’s cathedral and churches.

In Italy, in 1494, Dürer complains in a letter home of the bitter contrast between Nuremberg and Venice where painters like Titian and Giovanni Bellini are spoken of as heroes. ‘Here I am a gentleman, at home no more than a parasite.’4 In Venice he also signs his works with new flourish. ‘Albrecht Dürer the German brought this forth [exegit] in five months’ is the exultant inscription on one altarpiece, alluding to the poet Horace’s boast of bringing forth (exegit) a monument. That Dürer was alive to the originality of his own work is apparent from his campaigns against the pirating of his prints, and the AD logo, with which he signed every painting and drawing, was central to the celebrated lawsuit (a precedent, needless to say) in which he defended his intellectual copyright. Dürer’s first drawing is also his first self-portrait, made at the age of thirteen – the first example of such precocity in art.

Self-Portrait at 13, 1484 Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

It is a marvel in itself, this queer little drawing in silverpoint. Even so young, even starting out, Dürer does not do anything conventional. He does not draw in pencil or chalk, he does not draw something or someone easier. He does not even portray himself from the front but in three-quarter view, looking and pointing to the right, a set-up so challenging it probably involved more than one mirror. The medium is as tricky as possible since silverpoint, which involves drawing with a fine stylus on specially prepared paper, cannot be erased or corrected. Dürer’s father, a goldsmith, had already made a silverpoint self-portrait, in the same pose and holding one of the delicate tools of his trade; his son does nothing so humble. The right hand is not drawing, as it might have appeared in the mirror, nor holding anything so rudimentary as a stylus. In place of the tool is the boy’s gesturing finger, pointing to a world beyond that of the picture. And sure enough the future is all there in this little sheet of paper: virtuosity, incisiveness, the intense scrutiny and detachment, the fascination with everything from the individual strands of hair to the crumple and fold of fabric, stiff as carved wood. Even the elongated finger, elegant as his friends attest, is seen again in the 1500 self-portrait where pointing becomes even more significant.

Dürer’s art is always pointing things out, defining their likeness, making them visible and more of them than ever before. The tusks of a walrus, a greyhound’s quiver, the muzzle of a bull: superbly drawn and zoologically exact. Isolated on a page out of context, they look newly strange and wondrous; and things that are genuinely wondrous because imaginary – a merman, a horned devil, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse – seem actual because they are visualized out of observable truth.

The thirteen-year-old Dürer is a strange creature, too young to be producing such a work, and yet preternaturally wizened and aged: the child as father to the artist. Decades later, Dürer annotated the page with something like paternal pride: ‘This portrait of myself I made from a mirror in the year 1484 whilst I was still a child.’ Just noted for the record, as it seems, but to whom are these words addressed? Not to his descendants, for Dürer had no children, but to everlasting posterity.

‘I made this in five days.’ ‘This I made in awe when I was ill.’ ‘I saw this in Antwerp.’ Everything is annotated. There is more writing in Dürer’s art (and upon it, in the form of postscripts) than practically any other of that era and had he been an author there would surely have been meticulous volumes of autobiography. Time past can never be regained, or so it is said, but Dürer labours continually against this miserable dogma. He preserves everything, records everything, nothing must be lost to dust and oblivion. There are notebooks, travelogues and a long family chronicle; he wants to record in word and image everything he experiences, from the quotidian to the momentous. On the flyleaf of his copy of the new edition of Euclid he writes, ‘I bought this book at Venice for one ducat in 1507. Albrecht Dürer.’ On the tragic drawing of his mother in later life (which also records the strong family resemblance) he puts down the date, of course, and then ‘This is Albrecht Dürer’s mother when she was 63’ so that we would always know who she was and how she looked. Perhaps Dürer feared that she was mortally ill (he made portraits of both of his parents on the eve of his first trip to Italy, presumably in case he never saw them again). Not many days later, he adds the last words: ‘She passed away in the year 1514 on Tuesday before Cross Week two hours before nightfall.’ The portrait that begins as her living likeness becomes her epitaph.

Some years later Dürer draws himself half naked in the dire illness that probably overcame him during his search for the whale. One hand behind his back like a gallant about to bow, he points with the other to a circle inscribed around a point on his side and painted a delicate yellow. ‘There, where the yellow spot is located, and where I point my finger, there it hurts.’ The drawing was intended for his doctor and must be the most elaborate diagnostic aid in all art for it is a fully realized self-portrait in which the artist cannot suppress his mania for observation despite the suffering.

Self-Portrait in the Nude, c. 1503 Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

There are other drawings that probe – struggling to keep his face still in the mirror, head in hand, cheek awkwardly squashed; getting older; growing emaciated. But starkest of all is a full-frontal nude in which Dürer leans towards the glass to get a better look at himself, light striking his bony kneecaps and cheeks, the veins of his legs visibly standing, the long locks in a hairnet. Perhaps this is a man in his prime (he was approximately thirty-three) and certainly the torso is lean and strong, but it is an unstinting anatomy of nakedness, the dangling scrotum insidiously echoing the protuberant eyeballs, the cast in the left eye now more explicitly noted. Dürer is a peculiar sight even to himself, an alien creature in the world. The sense of an objectivity approaching estrangement is acute; Dürer, examining himself, sees something as strange as the wonders on his travels.

Dürer painted two self-portraits before the climax of 1500 and they have both been deplored as appallingly narcissistic. At twenty-two he looks pretty and girlish, clean-shaven in his raked cap with its scarlet cockade, fair hair artfully disarrayed. Other men in portraits of the period wear these ruched white shirts but never as low-cut as this. Between his fingers he holds an eryngium, an allusion to Christ’s suffering but also supposedly an aphrodisiac and guard against impotence. Whatever it meant to Dürer’s contemporaries in the arcane symbolism of the times it is displayed here, and depicted, as if it were some kind of outlandish scientific specimen, an object to be handled and examined. Some say this is a betrothal picture, painted on parchment so that it could be conveniently dispatched to his future wife. If so, and very unusually for Dürer there is no written evidence, then the inscription reads oddly. Next to the date, he makes the ambiguous announcement, ‘My affairs run as ordained from on high’, or in another translation, ‘as written in the stars’. Perhaps it is a declaration of piety, but if pious then not quite humble; and if a reference to the wedding then not quite enthusiastic, as if Dürer was having to resign himself to what was indeed an arranged marriage. It remains extremely hard to match the words to the image in any clinching sense, partly because it is impossible to read the tone and expression of the face. One commentator claimed to find nothing but vanity there; arguing that if the ‘painting breathes love at all, it is love of self’.5 Love of clothes, maybe; love of symbolism or botanical forms: this much is evident from the picture. But as for Dürer’s sense of himself, the face – expressionless, uninflected, exacting as a study of cowslips – gives nothing away.

Dürer was teased for his long hair in an age of collar-length cuts and took real pride in his outlandish coiffure, including the moustache – ‘sharpened and tuned’ as an acquaintance quipped – calling himself ‘the hairy bearded painter’ in a surviving fragment of doggerel.

Self-Portrait with Eryngium, 1493 Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

Goethe, who owned a complete edition of Dürer’s prints, praised his supreme vigour and ‘wood-carved manliness’. That is there in the prints, of course, but there is nothing manly about the way Dürer looks either at twenty-two or four years later in the Prado portrait. The costume is a deliberate challenge, part troubadour, part op-art couture, from the black and white stripes to the doeskin gloves (a Nuremberg speciality). Not only does the artist not portray himself painting, he defies the very notion of manual labour by presenting himself prophylactically gloved.

Self-Portrait with Gloves, 1498 Albrecht Durer (1471–1528)

Dürer is dressed as lavishly as the patrons he portrayed, striking the same pose and raised up to their social level. By now he was celebrated in Venice, had published the Apocalypse, his best-selling folio of prints, been praised to his face by Bellini. His clothes are a reward and a proof of success, along with the Italian landscape (a compositional first) framed through the window. The point of this picture is the whole combination: experience, money, cosmopolitan style, the picturing of oneself as a work of art, as a third-person portrait. For the painting says portrait – Nobleman with View – even though the inscription says self-portrait: ‘I made this from my own appearance when I was twenty-six.’ The face, all stillness and social standing, declares nothing except the strain of representing binocular vision. Far from the ‘pharisaical self-admiration’ that so appalled the English art historian John Pope-Hennessy, the narrow eyes do not speak of pleasure. There is no disclosure of self, no hint of the interior life. If you believe that clothes maketh the man you might conclude that this one is a peacock but the discrepancy between the showy clothes and the show-nothing face is sharply pronounced, almost a disconnect between outer and inner beings. Dürer may be his own protagonist here but subjectivity is by no means his subject. It is as if he has slipped himself into a portrait, adjusted the pictorial conventions so he can speak of himself in the third person as a man of mode and culture, a well-travelled man, a man who wears gloves when posing for a portrait. Dürer is thinking – as always – about pictures and picture-making and how he can exploit and reinvent them, just as in 1500 he would produce the most completely pictorialized of all self-portraits.

Painted at the midpoint of the millennium and exactly halfway through Dürer’s life, though he could not know it, this picture is cherished by German commentators as the epochal image of the German Renaissance, the triumphant face of German painting. Surely a man so conscious of his reputation must have envisaged such an outcome for his self-portrait, it is implied, and it is true that the image seems explicitly ordained. Scholars have been able to show that Dürer was looking at an actual frontispiece, in a new book by the German humanist Conrad Celtis,6 from which he may have extrapolated the configuration of lettering and image. At any rate, the Roman lettering, the insistently frontal depiction, the figure symmetrically cropped and contained by the frame: this is certainly the authorized face, Dürer as he intended to be seen and known. It was obviously never meant to stay quietly at home with the family for ever, like so many self-portraits, and indeed it must have had at least one ceremonial viewing within months of completion. Celtis, who was also Germany’s poet laureate, published a poem in its praise before the year was out.

How far did Dürer have to go to transform his own person into an icon? The earlier self-portraits, from the age of thirteen, add up to a time-lapse sequence in which the face is more or less recognizably that of one man, and he does not look very much like this. It is true that German mirrors were still quite primitive when Dürer was young – pieces of tin backed with lead, very often spherical – whereas the Venetian glass-blown mirrors he could later afford were comparatively sophisticated. But still the 1500 face is smoother, the cast in the eye less apparent, the hair a different colour; and to see what lengths Dürer would go to in the interests of advanced art you only have to consider those locks.

Straggly but generalized at twenty-two, they could still pass as approximately the same hair at twenty-six, softly brushed and realistic. But by 1500, there is nothing natural about them. They look more like the curling tendrils of a Wallachian ram than human hair, and in fact more like some sort of metal twine. Dürer was teased for his long hair in an age of collar-length cuts and took real pride in his outlandish coiffure, including the moustache – ‘sharpened and tuned’ as an acquaintance quipped – calling himself ‘the hairy bearded painter’ in a surviving fragment of doggerel. Even in crowded religious scenes his passing self-portrait will always be identifiable by the hank of hippy hair, but it is never as long as in the 1500 self-portrait and never so preternaturally curled and intertwined. This is fantastical hair and sticklers for forensic evidence can even consult the real lock taken from Dürer’s head two days after his death and cultishly preserved in a silver reliquary, now in Vienna, to see that the former looks unreal by comparison.

Dürer chose to represent his extraordinary hair and its weird reflective sheen with a precision so spectacular his contemporaries could scarcely believe it was done without magic, or at least without a magic brush. Bellini, according to Dürer practically the only painter in Venice who could view his works without envy, was so dazzled by the strand-by-strand depiction he imagined Dürer must possess a special brush that could be used to paint several hairs at one stroke; Dürer apparently responded with a private demonstration of his extra-special steadiness of hand. But against these exceptional powers of realization – the numbering of every hair, every twist – is an extreme and opposing artificiality that goes several ways. The hair is a triangle that points to the picture’s dimensions and the proportions of the figure. Or you might say it is arranged like a ceremonial headdress, or draped like a veil, or that its metallic sheen suggests something more numinous, like an aura or halo.

Certainly it alludes to the hair of Christ in icons, and specifically an icon by Van Eyck that Dürer is known to have admired. Anyone who saw the painting in Dürer’s day may even have been not so much struck as deceived by the resemblance. Koerner points out that the artist’s contemporaries would have seen so many icons, and so few portraits, especially with such distinctive compositions, that to them it probably looked more like an icon than a portrait.7 Dürer actually became the face of Christ for future German artists. His self-portrait appears in many prints and images as the face on Veronica’s Veil and a century after his death, Georg Vischer even cast Dürer without offence in Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery. There he is, right at the centre of the picture, radiating celestial light, his self-portrait by now a sacred relic; Dürer as the Holy Redeemer of German painting.

Vischer’s very queer picture, almost a collage with its cut-out figure and mismatching styles, makes one significant alteration to the original. His Dürer is making a straightforward gesture of blessing, whereas the hand in the 1500 self-portrait only teases at a benediction and it is not entirely clear what the fingers are actually doing.

This equivocation goes to the strangeness of the picture, the gesture being as hard to divine as the remote expression in the face. It also breaches the presentation of the portrait as an icon. It might seem that Dürer is just signalling his own identity according to a fairly conventional formula – here I am, here is the hand that made me – but he is not just, or not precisely, pointing to himself. He appears to be fumbling the fur of the lapel between his fingers, perhaps drawing attention to its texture as well as his own virtuosity in depicting such luxurious softness. But this fiddling is a taunt because it is so ostentatiously private. Whatever he feels, whatever he senses in his fingers, ought to connect straight up to the face, but when you get there all explanations are frustrated.

If the hand is a sign – pointing upwards, pointing to Dürer, pointing out his virtuosity – it is also a geometric crux that sends you back to picture-making. The principles of its own construction are so much part of the picture’s content that the little A of the logo chiming with the big A of the head is no accident and repeats the ingenious point in miniature: A is the artist, the artist is the image, a sign literally embodying the person, and incomparable art, of Albrecht Dürer.

Dürer died in Holy Week, 1528, a significant time for those inclined to worship the artist. ‘Whatever was mortal of Dürer,’ sighs the epitaph over the saint’s grave, ‘is covered by this tomb.’ Two days after his death the cherished lock of hair was cut and given to his assistant, the artist Hans Baldung. Three days after his burial, adoring students exhumed the body in order to make a death mask. By a most resonant coincidence, when the grave was again reopened in the nineteenth century by fanatics hoping to measure the divine proportions of Dürer’s head the body was gone and they found instead the corpse of a recently departed printmaker.

If Dürer had never painted the 1500 self-portrait then the unprecedented plethora of festivals held in his honour right up to the present day would all have lacked a figurehead. There would have been no face to carry like a monument through the streets of Nuremberg when he died. There would have been no altarpiece at which to worship for the nineteenth-century Nazarenes, those German artists also known as the Albrecht-Düreristen for their long hair, who gathered every year to celebrate the anniversary of his birth. There would have been no model for the bronze figure erected by mad King Ludwig of Bavaria in Nuremberg in 1840 – the first public statue ever to commemorate an artist – or for the miniature replicas of that statue, like little Eiffel Towers, that immediately went on sale as souvenirs of Nuremberg and its celebrated son.

Other works could have come to represent Dürer’s genius: the famous watercolour of the quivering hare, Knight, Death and the Devil, with its man of steel in a German helmet assailed by forces of evil, the mysterious Melancholia with its morose angel, face like thunder, sitting in her junkyard of allegorical symbols. But what else could represent the cult of Dürer, man and artist, better than the 1500 self-portrait in which he sets himself forth as an icon?

An icon ought to be awesome and so this one is with its coldly glowing charisma. Dürer comes before you, but he is as remote as a deity ought to be and fully as unreadable. In the very act of showing his face, Dürer put an unbreachable façade between himself and his viewers. You can see what he might have looked like, what marvels he could make of himself and his art, feel unnerved or entranced, but whatever your feelings before this self-portrait you are on your own. The artist remains a closed question. And although he supposedly establishes the whole tradition of self-portraiture, Dürer also shows that it has no straightforward course, for the example he set in 1500 was the first and last of its kind. Nobody could repeat this idea, this act of creation. It is the alpha and omega of self-portraits.