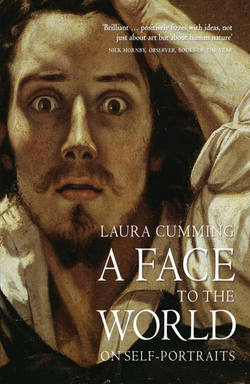

Читать книгу A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits - Laura Cumming, Laura Cumming - Страница 7

2 Eyes

Оглавление‘There is a road from the eye to the heart that does not go through the intellect.’

G. K. Chesterton

Detail of The Adoration Of the Magi, 1475 Sandra Botticelli (c. 1445–1510)

It would be hard to think of a more unnerving stare in Renaissance art than that of Sandro Botticelli, a painter better known for his dreamy visions of peace and love than for undertones of menace and coercion. Botticelli looks back at you, what is more, from a scene that ought to be all hushed and hallowed joy, the arrival of the wise men at Christ’s nativity. But even without his presence there is a sense of threat, for the miraculous birth has taken place in a derelict outhouse of yawning rafters and broken masonry that looks on the brink of collapse.

Between the viewer and the Holy Family, hoisted high for maximum visibility, mills a large crowd showing very varying degrees of respect, all played by members and attendants of the Florentine Medici. Botticelli includes two of his current patrons, Lorenzo and Giuliano, but also Piero the Gouty and Cosimo the Elder, both of whom were already dead at the time of painting. At the far right of this hubbub, in which at least two of the posse seem more adoring of their bosses than the Christ child, stands the artist himself. Stock still, full length, perfectly self-contained, he is the only figure set apart from the scene, muffled in his mustard-yellow robes like an assassin in a crowd, a Banquo’s ghost of a presence apparently visible only to us. The face is sullen, disdainful, unrelentingly forceful, the eyes trained upon you with a stare as cold as Malcolm McDowell’s in the poster for Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. A face, incidentally, that runs counter to the comfortable dog-and-owner theory of self-portraiture that artists tend to look right for their art – Van Gogh a fiery redhead with startling blue eyes, Rembrandt a rich ruin of a face – for it has no affinity with the sensuous rhythms of his work. The artist stands out not because he stands apart, but because of the look he gives the viewer. With a single glance, Botticelli turns the biblical scene into a confrontation.

Why is he here? What occasions his presence? Self-portraits often raise the question of their own existence. You might ask what could possibly justify the casting of the Medici as worshipful Magi, the rich miming the faithful, but this is obviously commemoration in the form of ostentatious prayer. Odd as it may seem to include a couple of deceased Medici, it was an expedient way of keeping their images alive before God and the congregation of Santa Maria Novella, just as Lorenzo and Giuliano would be eternalized in their turn; and if the patrons could appear in this elaborate fantasy, viewing and queuing and even occasionally stooping in awe, then why not the author of the painting itself?

Savonarola, apocalyptic preacher, burner of vanities and scourge of Florentine corruption who would later count Botticelli among his followers, railed against the shocking preponderance of secular portraits in religious frescos in those days. The churches were becoming a social almanac, a portrait gallery for local mafias. There they would be, witnessing martyrdoms, watching miracles, gazing at the Crucifixion – anything to appear in the picture. At least Botticelli did not cast himself as a wise man, but he does not play the family retainer either. His presence, his look, has a far greater purpose: to intensify the whole meaning of the painting.

The Adoration of the Magi, 1475 Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445–1510)

Eye-to-eye portraits were comparatively unusual in fifteenth-century Italy and congregations rarely saw a recognizable face looking directly back at them from a church fresco. Patrons generally appeared in worshipful profile. The sitters in independent portraits – paintings you could hang on the wall at home – were commonly presented in profile too, like a head on a medal, distanced and aloof, partly because they were often transcribed directly from frescos in the first place but also perhaps because profiles are so precise and economic, an enormous amount of information condensed and carried by a single authoritative line. The compiler of an inventory of paintings in Urbino in 1500 is surprised to come across a portrait ‘with two eyes’.1

Until Flemish portraits by Van Eyck and others started to arrive in Italy, with the revelation of a three-quarters view, it was unusual for a portrait to show more than one eye. This shift towards the viewer, this turning to communicate, was beginning to happen when Botticelli painted the senior Medici as Magi, but they still have the idealized remoteness of dead legends, whereas a singular vitality radiates from his eyes. The eyes are the strongest intimation, of course, that this is a self-portrait.

But Botticelli is not just putting in a proprietorial appearance, the painter painted. In The Adoration of the Magi, the self-portrait activates both the scene and its meaning. Just by turning and looking so challengingly at you, he shifts the tense so that the nativity no longer seems like ancient history but an incident of the moment, its significance forever urgent. There is fixation in that look, not just born of strained relations with the mirror, but perhaps of the kind that made Botticelli labour for twenty years over his never-finished illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy, or that would eventually drive him to destroy his own paintings in Savonarola’s notorious bonfire of the vanities. At any rate, the stare is a deliberate pressure, almost a demand or accusation. You who look so complacently upon this scene that I have envisaged for you – how deep is your adoration, your love?

Self-portraits catch your eye. They seem to be doing it deliberately. Walk into any art gallery and they look back at you from the crowded walls as if they had been waiting to see you. The eyes in a million portraits gaze at you too, following you around the room, as the saying goes, but rarely with the same heightened expectation. Come across a self-portrait and there is a frisson of recognition, something like chancing upon your own reflection.

This is self-portraiture’s special look of looking, a trait so fundamental as to be almost its distinguishing feature. Even quite small children can tell self-portraits from portraits because of those eyes. The look is intent, actively seeking you out of the crowd; the nearest analogy may be with life itself: paintings behaving like people.

Eye-to-eye contact with others – a glance, a stare – is the purest form of reciprocity. Until it ends, until one of us looks away, it is the simplest and most direct connection we can ever have. I look at you, you look at me: it is our first prelude, an introduction to whatever comes next; if we smile, shake hands, converse, get married, it will always be preceded by that first glance. We talk of eyes meeting across a crowded room, of recognizing each other immediately even though we had never met; we speak of love at first sight. Conversely we could not stand the sight of each other. Just one look was enough.

Since painted faces cannot hold your interest by changing expression, much depends on the character of that look. It is the first place we go, as in life, and if it is too tentative or blank or disaffected it might also be the last; the overture rebuffed. Some artists are disadvantaged from the start because they cannot get a fix on their eyes in the mirror, an aspect of excruciating strain that shows up in the picture exposing the pretence that they were ever looking at anyone but themselves. Others have to deal with spectacles or myopia or some insurmountable affliction, although the Italian painter Guercino movingly transformed the brutal squint he suffered from birth (Guercino means squinter) into a sign of unimpaired imagination by painting his eyes so deeply shadowed that one understands that this man’s vision turns inwards. His self-portrait shows, by concealment, what it might be like to have partial sight; mutatis mutandis, one sees what he sees. This is in the gift of self-portraits with perfect sight too of course. Whenever the look that originates in the mirror stays live and direct in the final image then the viewer should have a vicarious experience of being the artist – standing in the same relation he or she stood to the mirror, and the picture.

Self-Portrait, c. 1546–1548 Jacopo Comin Tintoretto (15I8–1594)

This sharpening of vision is very marked in a self-portrait Jacopo Tintoretto made in his late twenties. The Venetian turns to look our way and there is inquiry in his dark-eyed stare, a hook so strong you cannot immediately pull away for the sense of being held in his sights. The look is charged, the intensity meant, and abetted by other aspects of the image: the turning to stare over one shoulder, the gathering frown, appearing to cast a cold eye upon oneself in the encroaching darkness – no illusions, no fears – not to mention Tintoretto’s burning good looks.

It is an obvious and much-remarked fiction of self-portraiture that the viewer, rather than the artist, is the focus of all this intense interest. Tintoretto perfects the illusion. He has not gone right through the looking glass the way some artists do, their eyes worn blank by staring; he is not lost in self-contemplation, not caught in some infinite regression of looking at himself looking at himself, and so on. He is all attention.

The eyes are unusually large as if they dominated the other senses. Light catches the upper lid of the left and the lower rim of the right so that one has an uncommon sense of their spherical form within the socket. Perhaps these are the red rims of a man who painted with insomniac drive right through the night, creator of the tumultuous murals that cover wall after wall of the Scuola di San Rocco in Venice. At any rate, the eyes have their own special force of character and they have the reciprocal effect of making the viewer stare hard in return. It is no stretch of the imagination to feel you are both equally intent upon the other, but that you have also slipped into his position, seeing what he saw, entering into his self-knowledge. Centuries before anyone discovered how the eye actually works, Tintoretto has hit upon a true metaphor, for the eye is indeed an extruded part of the brain, drawing whatever it can of the outer world in through the retina to be transformed into neural images. Nowadays some specialists consider the eye a part of the mind itself, its freight of information modified by individual cognition, and even in Darwin’s day its curious status was enough understood for him to have written that ‘the thought of the eye makes me cold all over’.2 But Tintoretto, without any knowledge of the mechanics of seeing, senses the connection between mind and eye: to see is to know.

Look at me when I am talking to you, we say in pain or exasperation to those who have turned away – putting us out of sight and by implication out of mind. The simplest way for anyone to thwart our attentions, to block our access, is to look away. The barman who does not want to take an order will not meet the customer’s eye. The pedestrian who has stepped out in front of the car looks into the middle distance to avoid the motorist’s glare. An especially chilling way to deny another person is to stare straight through them as if they were just not there.

Self-Portrait, 1813 Anton Graff (1736–1813)

Self-Portrait with Spectacles, 1771 Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1699–1779)

This is precisely the look of many portraits where the sitter is supposedly a cut above – the royal portrait, say, or the duke on horseback – but most portraiture aims for some kind of connection. The Italian artist Giulio Paolini made the point in the 1960s by showing just how disconcerting it feels if this communion is deliberately thwarted. Paolini displayed a black and white reproduction of a Renaissance painting, Lorenzo Lotto’s Portrait of a Young Man, which shows a beautiful youth staring very candidly, and captivatingly, back at the viewer; or so it seems. But Paolini killed that illusion at a stroke simply by calling his version Young Man Looking at Lorenzo Lotto.

Common sense says this can only be true, that the sitter’s eyes were always on Lotto while he worked; but common sense is exactly what we naturally suppress when looking at the eye-to-eye portrait. It is our willing suspension of disbelief, our contribution to the occasion, and if the young man is no longer looking at us, if his eyes are refocused on someone else, then the party is over. The painting withdraws, becomes the record of two dead people looking at each other in some previous century, an effect of deflation and exclusion. It is the end of the rapport most portraitists want and exactly the opposite of self-portraiture’s aspiring eye-to-eye transmission of a first person encounter.

But an inept self-portrait will prove Paolini’s point quite unintentionally just by botching the eyes. The artist gets into a loop of looking at himself in the glass and reproducing that look that meets nothing but itself.

The Swiss-born painter Anton Graff is doing his best to see what he looks like, visor in position, brows pinched with effort. He poses as if turning aside from his latest commission, a portrait of some portly and presumably once-famous patron, but the pretence is not plausible for a moment. The Graff in the picture who wants to show himself doing what he does best – he was a very successful portraitist whose sitters included Schiller, Gluck and Frederick the Great – cannot really be working on that portrait, since he must be working on this self-portrait instead. And sure enough, he is trying so hard to paint both eyes in focus that you know he is really painting his own face. Graff’s gaze swithers; he cannot see us for the struggle to see himself.

A few decades earlier, Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin looks over the top of his pince-nez, one eyebrow raised with perceptible interest in an attitude of scrutiny that could not appear more sociable by comparison. The pose is almost humorous – who is not familiar with the rhetoric of lowering one’s spectacles as if pretending to consider someone else more pointedly – and the artist is at home in his jaunty bandanna, neck cloth loosely knotted against the cold, a note of domestic intimacy that runs through his work. But Chardin, now in his seventies, is both watchful and grave.

His eyesight failing and the smell of the oil paint he had used for half a century now making him ill, Chardin was forced to give up oil for pastel instead. The light focusing through the lens, the steel frames, the eyes with their glint of curiosity: all are achieved with this tricky medium, so easily blended and yet so fragile and fugitive.

Chardin is one of those artists whose self-portrait comes as a surprise – not because the face is so intelligent, for he has to be at least this clever to be the greatest still-life painter in art, but because it exists in the first place. Born in Paris in 1699, he never left the city except for a trip to Versailles. He has nothing to say about the wars, politics or public misery of his times, still less the private excesses of the aristocracy, although he must have seen it all for he had a city-centre flat in the Louvre. Chardin stayed at home, secretive, industrious, painting his apricots, strawberries and teacups, hymning the softness of a dead hare, the molten glow of a cherry. His power of touch runs all the way from the silvery condensation on a glass of water to the reflected glory inside a copper pan and the downy cheek of the housemaid dreaming over her dishes. Diderot, his earliest champion, called him ‘The Great Magician’, trying to fathom the mysteries of his art, of those muffled rooms where everything is misty and slightly distanced and warm air circulates like breath. But nobody ever saw him paint and scarcely a single anecdote attaches to Chardin’s life. That he should have left anything as personal as a self-portrait goes against the person of his art.

Self-Portrait, Wide-Eyed, 1630 Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–69)

That it is outwardly turned and makes such vivid eye contact is even less to be expected. For the look is distinctly interpersonal, making a quizzical connection with the viewer from the centre of the image, the perceptual heart of the picture. Chardin turns the same unhurried, penetrating gaze upon himself normally used to gauge the weight of a plum, the quiddity of an egg. You feel what it is to be one of his subjects, and what it is to be Chardin, eyes testing the truth of life directly.

Rembrandt is acting with his eyes. He hooks you by reeling back and showing the whites. The etching has been given the title Self-Portrait, Wide-Eyed but it might as well be called ‘Shocked to See You’. It is as if you personally have caused this effect: you come before him and he reacts, that is the one-two action of the image. The meeting of eyes amounts to an incident. And it is the same with almost all of Rembrandt’s self-portraits: he paints the eyes as pinpricks in shadow, or black holes, or dark discs you have to search for in the gloaming, trying to make the man out. He squints and he leers and he creases up to get a better look at you, a better sense of who you might be, identity always at issue.

Self-Portrait, c. 1655 Lorenzo Lippi (1606–65)

One of Rembrandt’s contemporaries, the Florentine poet and painter Lorenzo Lippi, goes even further with this line of inquiry, this idea that artists’ eyes do not just follow but actively seek you out, questioning who you are, with comic trepidation in his case. Lippi turns timidly towards us from the safety of the shadows, one eye out of sight as if hiding round the corner, the other swivelling fearfully in its socket. Who is there? The picture puts everyone on the spot.

Lippi’s ambition, he said, was to write poetry as he spoke and to paint as he saw3 and this likeness is quick and colloquial. But it is also a neat parody of the eyeballing business of self-portraiture: here is an artist bold enough to paint a portrait of himself yet who seems almost too scared to look. He has one eye on the viewer’s amusement.

Lippi seems to have been better known for his humour than his portraits in any case, spending much of his life at the court of Innsbruck painting respectful likenesses of the aristocrats while at the same time writing a serial mock epic satirizing their behaviour and mores to the mirth of devoted readers back home.4 His jesting image is now in the Uffizi self-portrait collection, still amusing the people of Florence. Unlike most of the many hundreds of paintings in that collection, it was not made especially for the occasion yet seems to have its current neighbours in mind, a mouse that hardly dares squeak among the great lions all around it whose pomp it quietly mocks. With his one-eyed peep Lippi achieves in a blink, what is more, what other artists can only hope for: an intimacy of connection, a kind of wink, in his case, that immediately brings the self-portrait to life.

Where to look? Anywhere but the mirror is an answer for the rare artist who rejects the rhetoric of intimacy. One of the few self-portraits to avoid eye contact altogether is also one of the greatest, painted by Titian in his mid-seventies. By now, the artist’s patrons have long since included popes, dukes, doges and most of the crowned heads of Europe and he shows himself as splendidly dressed as any of them, wearing the gold chains given him by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V who is supposed to have bowed his own knee to retrieve one of Titian’s dropped brushes (a folk-tale so gratifying to later artists that more than one painted the royal genuflection).

Titian sits at a table, this painter of kings and king of painters, one hand tensed against it, the other braced upon his thigh with the fingers powerfully outspread. A fellow artist who had been admitted to his studio in Venice reported that in these later years Titian often painted directly with his fingers, and one might imagine that the artist painted these magnificent hands with his own fingers, his supreme sense of touch evident in their very tips. But Titian is not painting in this self-portrait, of course – he is waiting, and this is the central tension of the picture. The body faces front, massively present, but the eyes turn away towards some invisible point beyond the picture. That you should still be here, that he should be here at all: these are the burdensome but inevitable conditions of self-portraiture, of appearing and being seen. But Titian manages to command your attention by diverting it, his eyes glancing free of yours.

Where to look when submitting oneself to scrutiny? It is a question that presents itself to the public-minded self-portraitist every time. In reality, we usually have some sense of who might be looking at us, especially if the circumstances are familiar. But artists can only see one person looking back from the mirror and have to imagine all the rest – anyone and everyone who might one day see their image – to compose a representative face. The politician filmed in some satellite studio unable to see his interrogator may be analogous, having no rival eyes on which to latch and forced to frame an expression without any guiding response. Under these circumstances, interviewees frequently look up, down or wanderingly off-centre, flustered by the voice in their ear, infuriated by the questions, or just withdrawn into tense concentration.

Self-Portrait, c. 1560 Titian (c. 1488–1576)

The eyes of self-portraits can expose an artist in just this way as dazed or perplexed, lost in drought or self-consciousness, or just defeated by the harsh technicalities. But few have retreated so far into self-consciousness as to have forgotten the world altogether. No matter how intimate the exchange between self and self-image, not many self-portraitists address only themselves, muttering alone in the studio. Self-portraiture is rarely an act of total introspection; attention is what it generally seeks. Some artists aim straight for the public address; others do so while making a pretence of seemly privacy – lowering the eyes, looking away off into the distance. Still others simply want to appear intimate, without giving much away. Joshua Reynolds manages to combine all three just by playing upon vision as a conceit.

Reynolds painted a great number of self-portraits with the public squarely in mind and many of them are unbearably self-serving. But in the best and most original, painted in his mid-twenties when he was just up to London from a Devonshire village and about to set off for the glories of Rome, his sights are set on the future and the road is open before him.

The dynamic young hero stares straight ahead, shielding his eyes against the light with one hand. Literally, he is looking at himself in the mirror but the gesture implies far wider horizons. With the maulstick held across the body like a sword, he also looks ready for the cut and thrust. He is on guard: the artist as saluting swordsman.

It is a variation on the studio self-portrait – the palette, the stick for steadying the hand at the canvas, even a hint of that canvas – but such an advance on the usual scenario. Reynolds makes a character of himself in a drama that is all about seeing and being seen and trying to get a better look at the world. The world, and himself, and his audience, and his painting – the gesture is pointedly specific yet all-encompassing; and then comes a further twist. His eyes are so deep in shadow, like those of Rembrandt, Reynolds’s hero, that it is impossible to tell whether they are truly fixed upon the viewer; and the implication of that shielding hand, what is more, is that it is in any case too bright to make out what lies ahead, that the artist can hardly see. Artist and viewer are ships in the night. Yet the hand against the light tells of a sighting!

‘A beautiful eye makes silence eloquent, a kind eye makes contradiction an assent, an enraged eye makes beauty deformed. This little member gives life to every other part about us; that is to say, every other part would be mutilated were not its force represented more by the eye than even by itself.’

Joseph Addison

Self-Portrait, c. 1747–49 Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–92)

Reynolds painted himself in Rembrandt beret, in the doctoral robes of Oxford University, contemplating a bust of Homer in the manner of Aristotle in Rembrandt’s etching. His sense of achievement was highly developed and his self-portraits are ceremonial – the one painted when he got the freedom of his home town, the one for the king when he took over the Royal Academy – and made for public display within a month or two, usually at the Royal Academy. But he sometimes produced less grandstanding works in which he comes more modestly downstage. In a late painting, now deaf, he cups a hand to his ear the better to hear us in a poignant reprise of this early gesture (his vision would eventually fade as well). Both pictures have a theatrical intimacy – Garrick on stage – that seems to single you out, to signal to you and you alone. They crave, and declare, an audience with these focusing gestures. But although Reynolds salutes the viewer, he has eyes not just for you but the whole wide world.

The eyes of most self-portraits are outwardly directed, seeking to be seen, but they may signify inner vision just as keenly. A head in close up, eyes like dark stars, was rare when Tintoretto painted himself in the sixteenth century but it became very common with Romanticism. The self is concentrated in the mind, the mind in the eyes, twin wells of feeling and thought. Cogito ergo sum translates as video ergo sum, and what I am may be manifest in my powers of vision. Self-portraiture’s special look goes well with this idea of the artist as seer, possessing gifted powers of insight. It is a look popular among the young – Samuel Palmer, at twenty-one, appears charismatically far-sighted, although it is partly the effect of not being able to draw both eyes in focus – and mocked by Picasso in old age. At ninety-one, eyes like mismatched marbles in a primitive mask, one dim and myopic, the other stuck open for ever like some dreadful twist of fate, he is halfway between animal and crazed old totem.

Absorption, 1919 Paul Klee (1879–1940)

There is a little self-portrait drawing by Paul Klee where the eyes are tight shut, so that one deduces that it cannot have been made by looking in a mirror but must effectively be a self-portrait from within, and quite possibly with sex in mind, for there is orgasmic concentration in the features. But what it enchantingly expresses is this idea that inspiration, vision, imagination, soul, everything that really matters in art, come in the end from within. And an extra quirk is that humorous Klee can never be accused of self-regard (an old accusation against self-portrayers) for he was not even looking at himself. What these eyes must have seen, what thoughts, what dreams: Klee’s self-portrait draws one intensely into his mind without following the usual invitation through the open eyes, a sweet retort to the old line about souls and windows. And one remembers that he did not make any distinction between the inner and outer worlds in his work. ‘Art does not render the visible,’ Klee said, ‘it renders visible.’ He was speaking mystically and what is rendered visible in his art is surely at the very least his own spirit – lightsome, benign, visionary, intimate and as comical as this little self-portrait.

What the eyes have seen, literally and metaphorically: this is the concern of all art. In this sense the eyes are the artist’s truest emblem and attribute. How perfect that they should also become the crux of an artist’s self-portrait, the focal point, the first line of communication between artist and viewer.

Yet no self-portraitist actually needs to meet our gaze directly to exert continuous pressure or keep our eyes upon his. This is nowhere more apparent than in an etching by Francisco Goya that speaks as powerfully with the eyes as Botticelli even though it does not even have the advantage of two and never fixes fast, or unequivocally, upon the viewer.

Goya turns slightly out of formal profile, throwing a sidelong glance out of the picture. The look is withering, as pungently directed outward as inward. It is an opening shot; it is the etching with which he prefaced Los Caprichos.

This volume of prints, unsurpassed in their terrifying visions of human violence and folly, avarice and cruelty, their riddling captions like the overheard speech of mysterious offstage commentators, goes so far beyond explanation into nightmare that it is often perceived as purely a figment of the artist’s tormented imagination, no matter that the voice of the captions declares ‘I saw this’ or ‘I was here’. Goya originally opened the volume with that deathless image of a man slumped over his desk, the air thronged with bats and evil critters that might indeed be issuing from his nightmares; and ‘The Sleep of Reason’ has been taken as an allegorical self-portrait depicting the source (and modus operandi) of all that follows. But Goya replaced it, significantly, with this likeness of himself as a top-hatted man of the world casting a cold eye upon the viewer.

Self-Portrait, pub. 1799 Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828)

It is an acerbic pastiche of the conventional famous-author portrait that has prefaced so many books, then and since. The profile puts the self-portrait straight into the third person: there is the author, Señor Goya, his name written below, corresponding precisely with Goya’s verbal description of himself throughout as el autor, or el pintor. And yet he breaks out of that profile, as if coming alarmingly alive. Facing left, he appears to turn his back upon what follows as if in disavowal; but then again, isn’t he rather like the kind of figures who occasionally turn up in the book? Goya may be the maker, or the narrator, but he is not above the vileness depicted herein.

We always say that in his images of sexual corruption, torture, war crimes, bullfights, Goya is the master of modern documentary, that whatever he had to say about the Spanish Inquisition or the horrors of the Napoleonic invasions of the early nineteenth century applies to Afghanistan or Abu Ghraib. The priest lusts, the paedophile rapes: the artist has seen it all and brought it back to us in its absolute horror. But it is very hard to read the tone of Goya’s art, to know who is speaking, who saw what, whether the talk is ever straight.

Look at that telling eye: it seems to swivel between there and here, then and now, between immediacy and distance. Pose and eye, taken together, make Goya both an observer and a man observed, the creator but also the subject. Yet the look is insinuating, and deviously incorporates the viewer. That left eye, half obscured by the heavy eyelid and nearly disappearing out of view, has you snared in its sights, for you and I are part of this too.