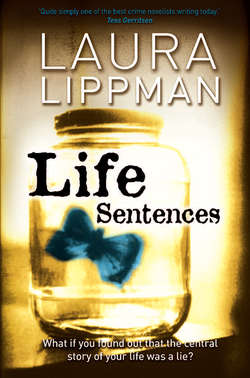

Читать книгу Life Sentences - Laura Lippman - Страница 15

Chapter Six

ОглавлениеWhere the hell is Banrock Station?

Teena Murphy put the box of chardonnay on the conveyor belt at Beltway Fine Wines, something she did—damn—every six days, on average, and it might have been a little more frequently, but she allowed herself vodka on the weekends. Yet this icy February day was the first time she had been moved to consider the name of her weeknight wine of choice. Box wine had many advantages—the price, the relative lightness of the carton, a key consideration for her—but Teena preferred it because she didn’t have to confront how quickly the level was dropping.

‘You having a party?’ a voice behind her asked, a playful tenor. ‘How come I wasn’t invited?’

She turned, surprised that anyone at Beltway Fine Wines would joke with her that way. Teena had been a knockout in her prime, but her prime was a long time ago. She had also let her hair go gray, which made her look older still, as did her small, fragile-seeming frame. People didn’t joke with slightly hunched, gray-haired ladies in the after-work rush at Beltway Fine Wines.

Unless they knew you once upon a time.

‘Lenhardt,’ she said. ‘What are you doing in my home away from home?’ If she made the joke, it couldn’t be true. Right?

Her former colleague laughed. He had aged, too, but then—it had been fifteen years, easy, since they had seen each other last. Teena still got invited to the Christmas parties, the retirement parties, even the homicide squad reunions, but she never attended. Her invitations may have arrived on the same paper, in the same envelopes as everyone else’s, but there was a whiff of pity about them. Pity and contempt.

‘You look good, Teenie,’ he lied. Even in his wilder days, between his two marriages, Lenhardt had been able to compliment a woman without making it sound like a pass.

‘You, too,’ she said, and it wasn’t as much of a reach. He looked as good as he ever had. Lenhardt—now in his fifties—had always been a little stocky, and there was only a touch of gray in his sandy hair.

‘Where you living these days?’

‘On Chumleigh, off York Road.’ Quickly, defensively, always aware of the gossip that she had cashed in on her misfortune. ‘West of York Road. And it wasn’t so expensive when I bought in.’

‘Chumleigh!’ He laughed at her blank look. ‘You don’t remember the cartoon Tennessee Tuxedo? His walrus friend, Chumley? And Don Adams was the voice of the penguin? No? Ah well, as a Baltimore Countian, you’re one of the citizens I’m charged with protecting and serving, not necessarily in that order. You working?’

‘At Nordstrom.’

‘Explains the fancy duds. But then—you always liked clothes, Teenie. I remember—’

‘Yeah,’ she said, not wanting him to finish the sentence: How excited you were when you got to join CID, wear your own clothes. She had dressed beautifully once she got out of uniform. It had been the eighties, not fashion’s finest hour in hindsight, and she had gone into credit-card debt for that outlandish wardrobe. It had been the age of fluffy excess—oversize shirts, big jewelry, riotous prints. She remembered one skirt with enormous cabbage roses. Oh, and those big Adrienne Vittadini sweaters, which someone of Teena’s height could practically wear as dresses.

Her colleagues had teased her, saying she looked like a punk, not getting that the look was, in fact, a romantic take on the downtown look. She had even been called in, told to tone it down, but her union rep had stepped in and said her clothes were within the guidelines for dress. The department was used to fashion plates, but the male version, peacocks strutting in expensive suits and ties. The other women in homicide, all two of them, went for that boring dress-for-success thing, suits and little bows. Teena would have rather gone back to wearing a uniform.

Now she wore dark, somber knits purchased at her employee discount. To sell other women expensive clothes, she had found it helped to have a neutral look, one that couldn’t be pinned down in terms of label or cost. Because, of course, that was the paradox of waiting on wealthy women, the unspoken accusation hurled out when someone discovered she couldn’t wear something new and trendy: What do you know? You can’t afford these things. But Teena knew the clothes better than anyone. She lived among them, day in and day out. She thought of her life at Nordstrom as akin to a position in some strange animal orphanage, full of exotic beasts that needed new homes. She was careful about matching her charges to their future owners, determined that the rarest specimens go to customers who were worthy of them.

‘It’s funny, running into you,’ Lenhardt said. His cart was filled with what Teena thought of as reputable purchases—three bottles of wine, a bottle of Scotch, a case of Foster’s. She wondered how long those would last him, how often he shopped here, if he drank one beer with dinner, or two, or three. ‘It was only a day or so ago that I got a call from someone looking for you. But that’s how it goes. You go years without seeing an old friend, then, boom, the name’s suddenly in the air. Ever notice that?’

The clerk loaded her box back into the shopping cart. Beltway Fine Wines had a distinctive smell that Teena could never quite pin down, a combination of wood, damp cardboard, and something spicy. She wondered if the various spirits under its roof slipped into the air. She always felt a little…altered when she was here, but then, she came here after work, when she was in the middle of the transition from work Teena to home Teena. No one called her Teenie anymore, but she still couldn’t carry her full name, Sistina.

‘Someone called you, looking for me?’

‘She was shut down by the public information officer in Baltimore City, I think, so she dug around, found some of your old compadres, those of us who jumped ship back in the early nineties. I guess she assumed we were disgruntled types, more likely to break rank. She was half-right.’

Lenhardt had left when a new chief tried to force a rotation system on the homicide squad. Teena might have joined the exodus, but she had her accident a few months later.

‘She?’

‘Some writer. Kinda famous, I think—I remember my wife reading one of her books for book club. She’s working on a new book.’ He swiped his credit card, took his bagged purchases from the clerk. Teena realized she was blocking other shoppers trying to make their way to the exit. She began rolling slowly forward, but Lenhardt caught up easily and fell into step beside her.

‘Why does she want to talk to me?’

He gave her a look. ‘Do you want to talk to her?’

‘No.’

‘That’s what I thought. I didn’t tell her anything. I didn’t have anything to tell, but if I had—I wouldn’t have, Teena. You know that.’

‘But—why? Why now?’

‘She just realized she knows—what was her name, the one who never talked?’

‘Calliope Jenkins.’ She felt like a child risking the candy man. Say the name three times and she’ll appear. Not that Teena was scared of Callie Jenkins. Not exactly.

‘Right. They went to school together.’

‘And that’s a book?’ Her voice screeched a little on the last word, but the whoosh of the automatic doors provided cover. They were outside now, and the wind was cutting, carrying little pinpricks of rain that stabbed exposed skin. She had forgotten to put her gloves on and her hands ached. The medical experts hired by the other side during the arbitration said Teena’s Raynaud’s was coincidental, that she couldn’t prove it was a direct result of the accident. Small-framed women were prone to it, they said. Still, Teena never minded the cold before the accident.

‘Her name is Cassandra Fallows,’ Lenhardt said. ‘This writer, I mean.’ He had followed her to her car and she had a pang of embarrassment at its plainness. An out-and-out hooptie would have been less humiliating than this green, well-kept Mazda, which seemed to announce to the world how small and dull her life was. ‘On caller ID, she comes up as a New York area code. Begins with a nine at any rate. In case she does find you. Although I admit I tried, out of curiosity, and your number is unlisted, although your address comes up readily enough through the Motor Vehicle Administration. Not that she can get that without driving down to headquarters in Glen Burnie. Still, you know, if she’s even a half-assed researcher, she’ll be able to find your address. Unless—you own or rent?’

‘Own.’

He grimaced. ‘Well, that’s good—I mean, rent is just throwing money away—but that makes it easier to find a person. Sorry, now I sound like your father. I am a father now. A boy and a girl, Jason and Jessica.’

‘Congratulations.’ She meant it. Being a father, a parent, seemed miraculous to her. Anything normal did. But her mind wasn’t really on Lenhardt’s kids. A writer, doing a book. Every couple of years or so, back when the case was fresher, she would get a letter from a reporter, usually someone new at the Beacon-Light, an eager kid who had just stumbled over the story. She should have expected this, with the New Orleans case kicking up Calliope’s name, however briefly. She herself had started when she heard the news. But it had been so long since anyone had spoken of Callie to her. That was another reason not to attend cop parties. No back-in-the-day, no war stories.

‘Bye, Lenhardt. It was nice seeing you.’

‘Maybe our paths will cross again,’ he said.

‘Maybe,’ she said. Especially if you shop here regularly.

She drove home and, as it often happened, was shocked to find herself there fifteen minutes later, panicky to realize that she had driven so mindlessly. She had always been prone to zone out that way. It was part of the reason she almost never drank outside the house—at her size and weight, a generous glass of wine could edge her over the legal limit. Oh, it couldn’t make her drunk—based on her consumption of box wine, it took quite a lot to make her drunk—but who would believe that, should Teena Murphy be pulled over in her fancy clothes and plain car? They would expect her to be drunk. It would explain how she survived being her.

Pulling into her parking pad, she heard something—a branch cracking perhaps—and almost jumped out of her skin. The sound was the only memory she had, and she wasn’t even sure if that was true or something her brain had manufactured after the fact. But any kind of snapping, cracking noise threw her into a panic. She couldn’t be sure, but she believed that she hadn’t screamed until she heard the sound, all those breaking, snapping bones, like twigs under a giant’s foot. In her ears, it sounded like scoffing laughter, someone taunting her. Not that Calliope Jenkins had even smiled, much less laughed, in all the time she had tried to talk to her over the years. Still, Teena always believed she was laughing on the inside, delighted by her ability to play them all.

The accident happened a couple of months after they announced Callie Jenkins’s release. Now that was sheer coincidence. Teena had gone to pick up a woman, the mother of a kid who had just been charged in a homicide, and the woman freaked out. Teena had always prided herself on not making the mistake of going for her gun too early, something women police were faulted for. Small as she was, she could and would take a beat-down. But she was tired that morning—not drunk—and she had gone for her gun, and the woman had knocked it out of her hand, sent it skittering under the car. Teena had been groping, grasping for it when the car started to roll backward.

She let herself into the small, neat rowhouse she had purchased with her settlement from the car manufacturer, the deep pocket that had finally swallowed responsibility for her accident. Oh, they didn’t admit the parking brake was faulty, and they had done enough research, her FOP lawyer said, to know they could pretty much destroy her credibility in court. They just decided it was cheaper to settle and what was nothing to a big car company was more than enough to buy this house, in cash, on Chumleigh Road. Chumley! Now she remembered. She had watched that cartoon. She just forgot. She forgot a lot. She was forty-six years old and she could barely believe that she was once a little girl who had watched cartoons, who had decided she wanted to apply to the police academy because of Angie Dickinson in Police Woman.

‘She’s part of the gimp lineup, you know,’ her father would say, referring to the other popular television shows of the day. ‘There’s a guy in a wheelchair, a blind guy, and a fat guy. She’s a woman, and that’s handicap enough.’ He wasn’t being mean, and he certainly didn’t know he was being prophetic, that his daughter would one day join the gimp lineup twice over. Her father simply never understood why a pretty girl—and, although he never said it, a straight girl—would choose a career in the Baltimore City police department. Teena didn’t dare to say it out loud, but she believed she could be the first female chief in the department’s history, the first woman in the nation to lead a big-city police department. In the seventies, it wasn’t weird to believe that kind of shit. Strange, now that there really were women heading departments—in Des Moines; in Jackson, Mississippi—it seemed less probable to her. When she had joined homicide in 1986, she was the third female detective. Now, twenty-two years later, there were…two female detectives.

Teena lifted the box of wine from her trunk, favoring her right hand, and cradled it on the point of her hip, the way a woman might carry a baby. She would eat something—a frozen dinner from Trader Joe’s, soup and a sandwich—forestall the first glass of wine just long enough to prove that she could. She would wash her dishes, tidy up the kitchen. Then, and only then, she would board the train for Banrock Station, chugging past all the other little towns on the route, all the places she would never know or visit.