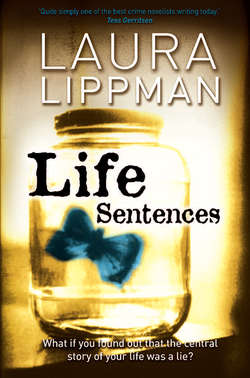

Читать книгу Life Sentences - Laura Lippman - Страница 7

Chapter One

Оглавление‘Well,’ the bookstore manager said, ‘it is Valentine’s Day.’

It’s not that bad, Cassandra wanted to say in her own defense. But she never wanted to sound peevish or disappointed. She must smile, be gracious and self-deprecating. She would emphasize how wonderfully intimate the audience was, providing her with an opportunity to talk, have a real exchange, not merely prate about herself. Besides, it wasn’t tragic, drawing thirty people on a February night in the suburbs of San Francisco. On Valentine’s Day. Most of the writers she knew would kill for thirty people under these circumstances, under any circumstances.

And there was no gain in reminding the bookseller—Beth, Betsy, Bitsy, oh dear, the name had vanished, her memory was increasingly buggy—that Cassandra had drawn almost two hundred people to this same store on this precise date four years earlier. Because that might imply she thought someone was to blame for tonight’s turnout, and Cassandra Fallows didn’t believe in blame. She was famous for it. Or had been.

She also was famous for rallying, and she did just that as she took five minutes to freshen up in the manager’s office, brushing her hair and reapplying lipstick. Her hair, her worst feature as a child, was now her best, sleek and silver, but her lips seemed thinner. She adjusted her earrings, smoothed her skirt, reminding herself of her general good fortune. She had a job she loved; she was healthy. Lucky, I am lucky. She could quit now, never write a word again, and live quite comfortably. Her first two books were annuities, more reliable than any investment.

Her third book—ah, well, that was the unloved, misshapen child she was here to exalt.

At the lectern, she launched into a talk that was already honed and automatic ten days into the tour. There was a pediatric hospital across the road from where I grew up. The audience was mostly female, over forty. She used to get more men, but then her memoirs, especially the second one, had included unsparing detail about her promiscuity, a healthy appetite that had briefly gotten out of control in her early forties. It was a long-term-care facility, where children with extremely challenging diagnoses were treated for months, for years in some cases. Was that true? She hadn’t done that much research about Kernan. The hospital had been skittish, dubious that a writer known for memoir was capable of creating fiction. Cassandra had decided to go whole hog, abandon herself to the libertine ways of a novelist. Forgo the fact-checking, the weeks in libraries, the conversations with family and friends, trying to make her memories gibe with hard, cold certainty. For the first time in her life—despite what her second husband had claimed—she made stuff up out of whole cloth. The book is an homage to The Secret Garden—in case the title doesn’t make that clear enough—and it’s set in the 1980s because that was a time when finding biological parents was still formidably difficult, almost taboo, a notion that began to lose favor in the 1990s and is increasingly out of fashion as biological parents gain more rights. It had never occurred to Cassandra that the world at large, much like the hospital, would be reluctant to accept her in this new role. The story is wholly fictional, although it’s set in a real place.

She read her favorite passage. People laughed in some odd spots.

Question time. Cassandra never minded the predictability of the Q-and-A sessions, never resented being asked the same thing over and over. It didn’t even bother her when people spoke of her father and mother and stepmother and ex-husbands as if they were characters in a novel, fictional constructs they were free to judge and psychoanalyze. But it disturbed her now when audience members wanted to pin down the ‘real’ people in her third book. Was she Hannah, the watchful child who unwittingly sets a tragedy in motion? Or was she the boy in the body cast, Woodrow? Were the parents modeled on her own? They seemed so different, based on the historical record she had created. Was there a fire? An accident in the abandoned swimming pool that the family could never afford to repair?

‘Did your father really drive a retired Marathon cab, painted purple?’ asked one of the few men in the audience, who looked to be at least sixty. Retired, killing time at his wife’s side. ‘I ask only because my father had an old DeSoto and…’

Of course, she thought, even as she smiled and nodded. You care about the details that you can relate back to yourself. I’ve told my story, committed over a quarter of a million words to paper so far. It’s your turn. Again, she was not irked. Her audience’s need to share was to be expected. If a writer was fortunate enough to excite people’s imaginations, this was part of the bargain, especially for the memoir writer she had been and apparently would continue to be in the public’s mind, at least for now. She had told her story, and that was the cue for them to tell theirs. Given what confession had done for her soul, how could she deny it to anyone else?

‘Time for one last question,’ the store manager said, and pointed to a woman in the back. She wore a red raincoat, shiny with moisture, and a shapeless khaki hat that tied under her chin with a leather cord.

‘Why do you get to write the story?’

Cassandra was at a loss for words.

‘I’m not sure I understand,’ she began. ‘You mean, how do I write a novel about people who aren’t me? Or are you asking how one gets published?’

‘No, with the other books. Did you get permission to write them?’

‘Permission to write about my own life?’

‘But it’s not just your life. It’s your parents, your stepmother, friends. Did you let them read it first?’

‘No. They knew what I was doing, though. And I fact-checked as much as I could, admitted the fallibility of my memory throughout. In fact that’s a recurring theme in my work.’

The woman was clearly unsatisfied with the answer. As others lined up to have their books signed, she stalked to the cash registers at the front of the store. Cassandra would have loved to dismiss her as a philistine, a troublemaker irritable because she had nothing better to do on Valentine’s Day. But she carried an armful of impressive-looking books, although Cassandra didn’t see her own spine among them. The woman was like the bad fairy at a christening. Why do I get to write the story? Because I’m a writer.

Toward the end of the line—really, thirty people on a wet, windy Valentine’s Day was downright impressive—a woman produced a battered paperback copy of Cassandra’s first book.

‘In-store purchases only,’ the manager said, and Cassandra couldn’t blame her. It was hard enough to be a bookseller these days without people bringing in their secondhand books to be signed.

‘Just one can’t hurt,’ said Cassandra, forever a child of divorce, instinctively the peacemaker.

‘I can’t afford many hardcovers,’ the woman apologized. She was one of the few young ones in the crowd and pretty, although she dressed and stood in a way that suggested she was not yet in possession of that information. Cassandra knew the type. Cassandra had been the type. Do you sleep with a lot of men? she wanted to ask her. Overeat? Drink, take drugs? Daddy issues?

‘To…?’ Fountain pen poised over the title page. God, how had this ill-designed book found so many readers? It had been a relief when the publisher repackaged it, with the now de rigueur book club questions in the back and a new essay on how she had come to write the book at all, along with updated information on the principals. It had been surprisingly painful, recounting Annie’s death in that revised epilogue. She was caught off guard by how much she missed her stepmother.

‘Oh, you don’t have to write anything special.’

‘I want to write whatever you want me to write.’

The young woman seemed overwhelmed by this generosity. Her eyes misted and she began to stammer: ‘Oh—no—well, Cathleen. With a C. I—this book meant so much to me. It was as if it was my story.’

This was always hard to hear, even though Cassandra understood the sentiment was a compliment, the very secret of her success. She could argue, insist on the individuality of her autobiography, deny the universality that had made it appealing to so many—or she could cash the checks and tell herself with a blithe shrug, ‘Fuck you, Tolstoy. Apparently, even the unhappy families are all alike.’

To Cathleen, she wrote in the space between the title, My Father’s Daughter, and her own name. Find your story and tell it.

‘Your signature is so pretty,’ Cathleen said. ‘Like you. You’re actually very pretty in person.’

The girl blushed, realizing what she had implied. Yet she was far from the first person to say this. Cassandra’s author photo was severe, a little cold. Men often complained about it.

‘You’re pretty in person, too,’ she told the girl, saving her with her own words. ‘And I wouldn’t be surprised if you found there was a book in your story. You should consider telling it.’

‘Well, I’m trying,’ Cathleen admitted.

Of course you are. ‘Good luck.’

When the line dispersed, Cassandra asked the bookstore manager, ‘Do you want me to sign stock?’

‘Oh,’ the manager said with great surprise, as if no one had ever sought to do this before, as if it were an innovation that Cassandra had just introduced to bookselling. ‘Sure. Although I wouldn’t expect you to do all of them. That would be too much to ask. Perhaps that stack?’

Betsy/Beth/Bitsy knew and Cassandra knew that even that stack, perhaps a fifth of the store’s order, could be returned once signed. So many things unspoken, so many unpleasant truths to be tiptoed around. Just like my childhood all over again. The book was number 23 on the Times’s extended list and it was gaining some momentum over the course of the tour. The Painted Garden was, by almost any standard, a successful literary novel. Except by the standard of the reviews, which had been uniformly sorrowful, as if a team of surgeons had gathered at Cassandra’s bedside to deliver a terminal verdict: Writing two celebrated memoirs does not mean you can write a good novel. Gleefully cruel or hostile reviews would have been easier to bear.

Still, The Painted Garden was selling, although not with the velocity expected by her new publisher, which had paid Cassandra a shocking amount of money to lure her away from the old one. Her editor was already hinting that—much as they loved, loved, loved her novel—it would be, well, fun if she wanted to return to nonfiction. Wouldn’t that be FUN? Surely, approaching fifty—not that you look your age!—she had another decade or so of life to exploit, another vital passage? She had written about being someone’s daughter and then about being someone’s wife. Two someones, in fact. Wasn’t there a book in being her?

Not that she could see. This novel had been cobbled together with a few leftovers from her life, the unused scraps, then padded by her imagination, not to mention her affectionate memories of The Secret Garden. (A girl exploring a forbidden space, a boy in a bed—why did she have to explain these allusions over and over?) On some level, she was flattered that readers wanted her, not her ideas. The problem was, she had run out of life.

Back in her hotel room, she over-ordered from room service, incapable of deciding what she wanted. The restaurant in the hotel was quite good, but she was keen to avoid it on this night set aside for lovers. Even under optimal circumstances, she had never cared for the holiday. It had defeated every man she had known, beginning with her father. When she was a little girl, she would have given anything to get a box of chocolates, even the four-candy Whitman’s Sampler, or a single rose. Instead, she could count on a generic card from the Windsor Hills Pharmacy, while her mother usually received one of those perfume-and-bath-oil sets, a dusty Christmas markdown. Her father’s excuse was that her mother’s birthday, which fell on Washington’s, came so hard on the heels of Valentine’s Day that he couldn’t possibly do both. But he executed the birthday just as poorly. Her mother’s birthday cakes, more often than not, were store-bought affairs with cherries and hatchets picked up on her father’s way home from campus. It was hard to believe, as her mother insisted, that this was a man who had wooed her with sonnets and moonlight drives through his hometown of DC, showing her monuments and relics unknown to most. Who recited Poe’s ‘Lenore’—And, Guy de Vere, hast thou no tear?—in honor of her name.

One year, though, the year Cassandra turned ten, her father had made a big show of Valentine’s Day, buying mother and daughter department store cologne, Chanel No. 5 and lily of the valley, respectively, and taking them to Tio Pepe’s for dinner, where he allowed Cassandra a sip of sangria, her first taste of alcohol. Not even five months later, as millions of readers now knew, he left his wife. Left them, although, in the time-honored tradition of all decamping parents, he always denied abandoning Cassandra.

Give her father this: He had been an awfully good sport about the first book. He had read it in galleys and requested only one small change—and that was to safeguard her mother’s feelings. (He had claimed once, in a moment of self-justification, that he had never loved her mother, that he had married because he felt that a scholar, such as he aspired to be, couldn’t afford to dissipate his energies. Cassandra agreed to delete this, although she suspected it to be truer than most things her father said.) He had praised the book when it was a modest critical success, then hung on for the ride when it became a runaway bestseller in paperback. He had been enthusiastic about the forever-stalled movie version: Whenever another middle-aged actor got into trouble with the law, he would send along the mug shot as an e-mail attachment, noting cheerfully, ‘Almost desiccated enough to play me.’ He had consented to interviews when she was profiled, yet never pulled focus, never sought to impress upon anyone that he was someone more than Cassandra Fallows’s father.

Lenore, by contrast, was often thin lipped with unexpressed disapproval, no matter how many times Cassandra tried to remind people of her mother’s good qualities. Everyone loves the bad boy. Come April, her father would be center stage again, and there was nothing Cassandra could do about that.

She sighed, thinking about the unavoidable trip back to Baltimore once her tour was over, the complications of dividing her time between two households, the special care and attention her mother would need to make up for her father being lionized. Did she dare stay in a hotel? No, she would have to return to the house on Hillhouse Road. Perhaps she could finally persuade her mother to put it up for sale. Physically, her mother was still more than capable of caring for the house, but that could change quickly. Cassandra had watched other friends dealing with parents in their seventies and eighties, and the declines were at once gradual and abrupt. She shouldn’t have moved away. But if she hadn’t left, she never would have started writing. The past had been on top of her in Baltimore, suffocating and omnipresent. She had needed distance, literal distance, to begin to see her life clearly enough to write about it.

She turned on the television, settling on CNN. As was her habit on the road, she would leave the television on all night, although it disrupted her sleep. But she required the noise when she traveled, like a puppy who needs an alarm clock to be reminded of its mother’s beating heart. Strange, because her town house back in Brooklyn was a quiet, hushed place and the noises one could hear—footsteps, running water—were no different from hotel sounds. But hotels scared her, perhaps for no reason greater than that she’d seen the movie Psycho in second grade. (More great parenting from Cedric Fallows: exposure to Psycho at age seven, Bonnie and Clyde when she was nine, The Godfather at age fourteen.) If the television was on, perhaps it would be presumed she was awake and therefore not the best choice for an attack.

Her room service tray banished to the hall, she slid into bed, drifting in and out of sleep against the background buzz of the headlines. She dreamed of her hometown, of the quirky house on the hill, but it was 4 A.M. before she realized that it was the news anchor who kept intoning Baltimore every twenty minutes or so, as the same set of stories spun around and around.

‘…The New Orleans case is reminiscent of one in Baltimore, more than twenty years ago, when a woman named Calliope Jenkins repeatedly took the Fifth, refusing to tell prosecutors and police the whereabouts of her missing son. She remained in jail seven years but never wavered in her statements, a very unique legal strategy now being used again….’

Unique doesn’t take a modifier, Cassandra thought, drifting away again. And if something is being used again, it’s clearly not unique. Then, almost as an afterthought, Besides, it’s not Kuh-lie-o-pee, like the instrument or the Muse—it’s Callieope, almost like Alley Oop, which is why Tisha shortened her name to Callie.

A second later, her eyes were wide open, but the story had already flashed by, along with whatever images had been provided. She had to wait through another cycle and even then, the twenty-year-old photograph—a grim-faced woman being escorted by two bailiffs—was too fleeting for Cassandra to be sure. Still, how many Baltimore women could there be with that name, about that age? Could it—was she—it must be. She knew this woman. Well, had known the girl who became this woman. A woman who clearly had done something unspeakable. Literally, to take another word that news anchors loved but seldom used correctly. To hold one’s tongue for seven years, to offer no explanation, not even the courtesy of a lie—what an unfathomable act. Yet one in character for the silent girl Cassandra had known, a girl who was desperate to deflect all attention.

‘This is Calliope Jenkins, a midyear transfer,’ the teacher had told her fourth-graders.

‘Callieope.’ The girl had corrected her in a soft, hesitant voice, as if she didn’t have the right to have her name pronounced correctly. Tall and rawboned, she had a pretty face, but the boys were too young to notice, and the girls were not impressed. She would have to be tested, auditioned, fitted for her role within Mrs Bryson’s class, where the prime parts—best dressed; best dancer; best personality; best student, which happened to be Cassandra—had been filled back in third grade, when the school had opened. These were not cruel girls. But if Calliope came on too fast or tried to seize a role that they did not feel she deserved, there would be trouble. She was the new girl and the girls would decide her fate. The boys would attempt to brand her, assign a nickname—Alley Oop would be tried, in fact, but the comic strip was too old even then to have resonance. Cassandra would explain to Calliope that she was named for a Muse, as Cassandra herself had almost been, that her name was really quite elegant. But it was Tisha who essentially saved Calliope’s young life by dubbing her Callie.

That was where Cassandra’s memories of Callie started—and stopped. How could that be? For the first time, Cassandra had some empathy for the neighbors of serial killers, the people who provided the banalities about quiet men who kept to themselves. Someone she knew, someone who had probably come to her birthday parties, had grown up to commit a horrible crime, and all Cassandra could remember was that…she was a quiet girl. Who kept to herself.

Fatima had known her well, though, because she had once lived in the same neighborhood. And Cassandra remembered a photograph from the last-day-of-school picnic in fourth grade, the girls lined up with arms slung around one another’s necks, Callie at the edge. That photo had appeared, in fact, along with several others on the frontispiece of her first book, but only as testimony to the obliviousness of youth, Cassandra’s untroubled, happy face captured mere weeks before her father tore their family apart. Had she even mentioned Calliope in passing? Doubtful. Callie simply didn’t matter enough; she was neither goat nor golden girl. Tisha, Fatima, Donna—they had been integral to Cassandra’s first book. Quiet Callie hadn’t rated.

Yet she was the one who grew up to have the most dramatic story. A dead child. Seven years in jail, refusing to speak. Who was that person? How did you go from being Quiet Callie to a modern-day Medea?

Cassandra glanced at the clock. Almost five here, not yet eight in New York, too early to call her agent, much less her editor. She pulled on the hotel robe and went over to the desk, where her computer waited in sleep mode. She started an e-mail. The next book would be true, about her, but about something larger. It would include her trademark memories but also a new story, a counterpoint to the past. She wouldn’t track down just Callie but everyone she could remember from that era—Tisha, Donna, Fatima.

Cassandra was struck, typing, by how relatively normal their names had been, or at least uniform in spelling. Only Tisha’s name stuck out and it was short for Leticia, which might explain why she had been so quick to save Calliope with a nickname. Names today were demographic signifiers and one could infer much from them—age, class, race. Back then, names hadn’t revealed as much. Cassandra threw that idea in there, too, her fingers racing toward the future and the book she would create, even as her mind retreated, hopscotching through the past, to fourth grade, then ninth grade, back to sixth grade—her breath caught at a memory she had banished years ago, one described in the first book. What had Tisha thought about that? Had she even read My Father’s Daughter?

Yet Callie would be the central figure of this next book. She must have done what she was accused of doing. Had it been a crime of impulse? An accident? How had she hidden the body, then managed not to incriminate herself, sitting all those years in jail? Was there even a plausible alternative in which Callie’s son was not dead? Was she protecting someone?

Cassandra glanced back at the television screen, watched Callie come around again. Cassandra understood the media cycle well enough to know that Callie would disappear within a day or two, that she was a place-marker in the current story, the kind of footnote dredged up in the absence of new developments. Callie had been forgotten and would be forgotten again. Her child had been forgotten, left in this permanent limbo—not officially dead, not even officially missing, just unaccounted for, like an item on a manifest. A baby, an African-American boy, had vanished, with no explanation and yet no real urgency. His mother, almost certainly the person responsible, had defeated the authorities with silence.

That’s good, Cassandra told herself. She put that in the memo, too.