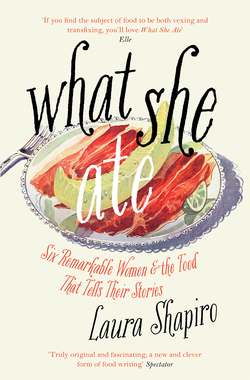

Читать книгу What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories - Laura Shapiro, Laura Shapiro - Страница 7

Introduction

ОглавлениеTell me what you eat,” wrote the philosopher-gourmand Brillat-Savarin, “and I shall tell you what you are.” It’s one of the most famous aphorisms in the literature of food, and I thought about it many times as I was probing the lives of the six women in this book. Food was my entry point into their worlds, so naturally I wanted to know what they ate, but I wanted to know everything else, too. Tell me what you eat, I longed to say to each woman, and then tell me whether you like to eat alone, and if you really taste the flavors of food or ignore them, or forget all about them a moment later. Tell me what hunger feels like to you, and if you’ve ever experienced it without knowing when you’re going to eat next. Tell me where you buy food, and how you choose it, and whether you spend too much. Tell me what you ate when you were a child, and whether the memory cheers you up or not. Tell me if you cook, and who taught you, and why you don’t cook more often, or less often, or better. Please, keep talking. Show me a recipe you prepared once and will never make again. Tell me about the people you cook for, and the people you eat with, and what you think about them. And what you feel about them. And if you wish somebody else were there instead. Keep talking, and pretty soon, unlike Brillat-Savarin, I won’t have to tell you what you are. You’ll be telling me.

One of the reasons I began writing about women and food more than thirty years ago was that I was full of questions like these, and I couldn’t find enough to read to satisfy my, well, hunger. Plainly women had been feeding humanity for a very long time, but for some reason only the advertising industry seemed to care. History, biography, even the relatively new field of women’s studies weren’t producing what should have been floods of books on female life at the stove or the table. I couldn’t figure it out. Surely women spent more time in the kitchen than they did in the bedroom, yet everybody was studying women and sex, and nobody was studying women and cooking except the companies selling cake mix. Maybe because I was a journalist, not an academic, it struck me as obvious that everyday meals constitute a guide to human character and a prime player in history; but I began to see that food was a tough sell in the scholarly world. The great minds were staunchly committed to the same great topics they had been mulling for centuries, invariably politics, economics, justice, and power. Today we know that all these issues and more can be brought to bear on the making of dinner—those stacks of books that were once missing are piled high by now—but back then the great minds, not to mention most of their graduate students, were reluctant to descend to the frivolous realm of the kitchen. After all, academic reputations were at stake. Home cooking was associated with women, which was bad enough, and housework, which was fatal.

Luckily I had come of age writing for the alternative press, where we made a point of ignoring any precepts set down by the great minds, so when I began working on my first book there was nothing to stop me from asking people what they ate and why. I posed these questions to the dead, primarily—a luxury unknown in journalism, but I realized that if I thought of myself as a writer of history, I had many more sources available and none of them could hang up on me. Over the years that followed, as I explored women and food in different eras of American life, I focused chiefly on pacesetters and enthusiasts, the women whose work in the kitchen had made an impact beyond their own lives. Then I had an experience that sent me in a different direction.

One night, bleary with insomnia, I had been staring at a bookshelf for a long time when I finally pulled out a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth. All I hoped to gain from this choice was a short, peaceful visit to the Lake District, where she famously kept house for her brother William—a visit that would lull me back to sleep. Sure enough, here was the calm, sweet record of their years in Dove Cottage: William devoting himself to poetry, Dorothy devoting herself to William, both of them aloft in reveries inspired by the mountains, the clouds, the birds, and of course the daffodils. Then William married, I skipped a few chapters, and Dorothy turned up in a dreary village far from the Lake District, now making a home for her nephew, the local curate. It was winter; she seemed to spend a lot of time trying to improve his sermons, a desultory cook was giving them black pudding for dinner—and suddenly I was wide-awake. Black pudding, that stodgy mess of blood and oatmeal, plunked down in front of Dorothy Wordsworth, the daffodil girl? There had to be a story.

And there was—a story that opened up a startling perspective on a woman I thought I knew. As soon as I was jolted into focusing on how she cooked and ate, the whole picture of her life seemed to shift, like a holographic image that changes as you tilt it. I had always imagined her as a kind of folk heroine of the Romantic movement, enshrined in the imagery of the Lake District until at fifty-seven she began a descent into sickness and dementia. Conventional wisdom sees these later years as a tragedy and leaves them at that, but conventional wisdom isn’t looking at the food. The food was telling me something else about Dorothy’s long decline, something I found both disturbing and oddly reassuring. Dorothy’s food story became my first.

In this book, I take up the lives of six women from different centuries and continents—women who cooked and women who didn’t—and in recounting these lives, I’ve placed the food right up front where I believe it belongs. Food, after all, happens every day; it’s intimately associated with all our appetites and thoroughly entangled with the myriad social and economic conditions that press upon a life. Whether or not we spend time in a kitchen, whether or not we even care what’s on the plate, we have a relationship with food that’s launched when we’re born and lasts until we die. As a writer who’s been curious for decades about what prompts people to cook and eat the way they do, I’ve often marveled at the emotional and psychological baggage we bring to the table, baggage we’ve generally been lugging around since childhood. Cooking, eating, feeding others, resisting or ignoring food—it all runs deep, so deep that we may not even notice the way it helps to define us. Food constitutes a natural vantage point on the history of the personal.

Today, of course, popular culture is on a culinary binge; and so much personal writing is now devoted to gazing back upon the kitchen and the table that we’ve had to invent a new literary genre, the food memoir, to contain all of it. But this mania is recent. Biography as it’s traditionally practiced still tends to honor the old-fashioned custom of keeping a polite distance from food. We’re meant to read the lives of important people as if they never bothered with breakfast, lunch, or dinner, or took a coffee break, or stopped for a hot dog on the street, or wandered downstairs for a few spoonfuls of chocolate pudding in the middle of the night. History respects the food stories of chefs and cookbook writers and perhaps takes note when a painter or a politician happens to be a gastronome as well; but in the published accounts of most other lives, the food has been lost.

And it really is a loss, because food talks. Food talks whether the meal is sitting on the table or never leaves the recipe box. In May 1953 the popular and prolific food writer Nell B. Nichols, who had a regular column in the Woman’s Home Companion called “Nell B. Nichols’ Food Calendar,” selected May 8 as the right day to offer a recipe for peanut-butter sandwiches that had been dipped in an egg-and-milk batter and then fried. We’ll never know the reactions of any family that might have been offered this surprising variation on French toast. We’ll never even know if a homemaker was inspired to prepare it. What we do know is that Nell B. Nichols, tapping into the food corner of the nation’s collective imagination, pulled out a culinary artifact worthy of being titled American Gothic. The food tells us everything. It tells us about our powerful loyalty to peanut butter, first of all, and our willingness to follow it across any terrain. It tells us how midcentury American cooks liked to color outside the lines while holding fast to the coloring book. And of course it tells us about the national palate, stunned into acquiescence after decades of gastronomic novelties dreamed up by the food industry.

Food always talks. The arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan, who became friends with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, wrote once that Stein “had a laugh like a beefsteak. She loved beef, and I used to like to see her sit down in front of five pounds of rare meat three inches thick and, with strong wrists wielding knife and fork, finish it with gusto, while Alice ate a little slice, daintily, like a cat.” Many, many people wrote about visiting Stein and Toklas in their famous Paris flat, but we have few descriptions as succinct and revelatory as this one. Luhan noticed the food.

Food talks—but somebody has to hear it. William Knight, the philosophy professor who was one of the first and most dedicated scholars of the Wordsworths, read through Dorothy Wordsworth’s journals early on and decided they should be edited for publication. Dorothy had been a close observer of William as he worked, and the two of them were at the center of a swirl of family and literary relationships important to his poetry. Unaccountably, however, the journals were also littered with what Knight called “numerous trivial details” of Dorothy’s housekeeping. He couldn’t think of a single reason why posterity would ever want to know what Dorothy cooked or sewed, and it certainly didn’t occur to him that the prose devoted to such chores might be worth reading for its own sake. One gets the sense from Knight’s brief preface to the journals, which he published in 1897, that he was a little irritated by all the meals and domestic doings that Dorothy insisted on telling him about, possibly at the expense of providing more information about the great Romantic. “There is no need to record all the cases in which the sister wrote, ‘To-day I mended William’s shirts,’ or ‘William gathered sticks,’ or ‘I went in search of eggs,’ etc. etc.,” Knight explained wearily. He assured readers that he had snipped out only the material that plainly lacked “literary or biographical value.” Later editors put the shirts and the eggs right back in; and to this day the Grasmere Journal is recognized as a classic of intimate prose, with a charm that has outlasted a fair amount of her brother’s verse.

This dismissive attitude toward women’s domestic lives continued to flourish for another century or so. Indeed, the very term “trivial” would come to haunt the post–World War II British novelist Barbara Pym, who loved nothing better than to include a mention of tinned spaghetti when she was constructing a character, though she knew such homely references were considered unworthy of serious fiction. “People blame one for dwelling on trivialities,” reflects one of her heroines, who can’t figure out why the lemon marmalade is taking so long to jell. “But life is made up of them.”

Dorothy Wordsworth and Barbara Pym, both irresistible to me precisely because of those “trivial details,” were the first two women I chose for this book. Over the next few years they were joined by an Edwardian-era caterer, Rosa Lewis; a First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt; a notorious mistress, Eva Braun; and an editor, Helen Gurley Brown. Obviously none of these women represents anyone but herself: each stood out dramatically from the female world into which she was born, and each has attracted enough scholarship, journalism, anecdotes, gossip, and downright fantasy over the years to win a secure spot in history. But what struck me as I followed the paper trail through each life was that while extraordinary circumstances produce extraordinary women, food makes them recognizable. If the emotional substance of these food stories rings familiar, it’s because they tend to be as messy and discomfiting as our own.

It’s easy, it’s practically automatic, to associate cooking and eating with our warmest emotions, and to keep that image on permanent pause, with a family forever beaming as Norman Rockwell carries the turkey to the table. Perhaps there are women whose food stories really do land them in such a cozy domestic category. To me it seems more likely that we’re just not accustomed to scrutinizing the food as vigorously as we scrutinize a woman’s education, or her marriage, or the poetry she writes. What I saw on the surface of each woman’s culinary life was never the whole picture. Digging deeper into her food story took me to a more tenuous emotional realm—sometimes I thought of it as the underside of the Rockwell painting—where all those feelings that we’re trying not to notice start dribbling down the sides of the bowls and crawling out from under the platters. I don’t mean to imply that these women were unhappy; they weren’t. By most measures they experienced quite a bit of contentment and success. But in every instance, opening a window on what she cooked and ate cast a different light on the usual narrative of her life. It turns out that our food stories don’t always honor what’s smartest and most dignified about us. More often they go straight to what’s neediest.

Every life has a food story, and every food story is unique. As we move from chapter to chapter in this book, however, we’ll find that the themes emerging from each woman’s relationship with food not only reflect her own moment, but reach into ours as well. Dorothy Wordsworth, for instance, who starts off the book, appears at first to be something of an outlier, for she was born in the late eighteenth century—so much earlier than the other women that they would have regarded her culinary world as impossibly primitive. But apart from her spelling and capitalization, which of course reflected habits of her time, I found nothing old-fashioned about her descriptions of the meals she shared with William. It’s true, she practically ignored the flavor and texture of the food itself, which no food writer today would dream of doing. This is far from the heavy-breathing school of culinary reportage. But the mere presence of William at the table, sometimes lost in poetry as he sat there, was enough to send a wave of ecstasy through her account of the meal. “While we were at Breakfast that is (for I had Breakfasted) he, with his Basin of Broth before him untouched & a little plate of Bread & butter he wrote the Poem to a Butterfly!” she scrawled in her diary, so excited she lost track of the pronouns. “He ate not a morsel,” she added, “nor put on his stockings but sate with his shirt neck unbuttoned, & his waistcoat open while he did it.” Later in life, too, she exposed her appetites more nakedly than anyone else in this book, at least until we reach Helen Gurley Brown, whose prose also radiated adoration for a man but gave it rather a different spin.

The next chapter introduces Rosa Lewis, the British caterer and social striver, and a food story riddled with the pressures of class. Cooking and eating are always ruled by a tangle of social and economic realities that define a woman’s place in her particular world, and in Rosa’s time the class implications lodged even in a sandwich could be formidable. According to a food column in The New York Times in 1894, only a “day laborer” should be eating a sandwich made from thick slices of bread and stuffed with hefty chunks of meat. For ladies, an appropriate sandwich would measure no more than half an inch, “and its flavoring or filling is delicate and dainty, a suggestion rather than a substantial reality.” Nuances like these made sense to Rosa, who grew up in the servant class but escaped it by mastering the rarefied cuisine demanded by her rich and titled clients. White grapes and truffles went into her champagne ices, she told an interviewer; and she used to forage the markets for young, tender vegetables—“What you call ‘premier,’” she said, or at least that’s how the word was transcribed in the interview. In truth she was using the French term for those baby vegetables—primeurs—but the difference had been swallowed up in her brash Cockney accent. These were complicated jousts: the food could climb the social ladder, but sometimes the cook was left behind.

Eleanor Roosevelt comes next, with a food story dominated by her marriage—like class, a persistent theme in women’s relationships with food, though clearly Eleanor’s marriage was public to a degree that most couples don’t have to endure. She and FDR built what many historians have described as a grand political partnership, but it was also a union marked by culinary discords that reverberated into every corner of Eleanor’s life. Numerous references to their meals are scattered throughout the voluminous Roosevelt papers, and none speak well for the power of food to bring two hearts together. So far apart were their appetites that when FDR relaxed with a cocktail and a few smoked clams at the end of the day—a ritual he cherished—Eleanor often stayed away. She rarely touched alcohol, and the idea of spending money on a luxury like tinned clams, especially during the Depression, appalled her. George Eliot once remarked that men seemed to get a great deal of pleasure from the “dog-like attachment” of their wives, but this was not Eleanor’s approach to marriage. “He might have been happier with a wife who was completely uncritical,” she admitted. On many nights, dinner in the White House was served in two different rooms.

Eva Braun’s food story, generated as it was by her devotion to Adolf Hitler, might appear to take place strictly within an appalling realm of its own; and to an extent, it does. But despite the moral distance that separates her from everyone else in this collection, there are elements in her relationship with food that we’ve seen in other chapters. Like Dorothy, she always had her gaze fixed on the man she loved. Like Rosa, she was thrilled by her access to a higher social rank. What emerges most vividly in Eva’s relationship with food, however, is her powerful commitment to fantasy. She was swathed in it, eating and drinking at Hitler’s table in a perpetual enactment of her own daydreams. For propaganda reasons, she was not allowed to appear in public with Hitler, which meant that she had no truly gratifying forum in which to show herself off as the Führer’s chief consort. Only the lunches and dinners he took with members of his immediate circle allowed her to bask in a role for which she had trained by studying movie and fashion magazines. At these meals, her glory visible and her status secure, she treated food as a kind of servant whose most important job was to keep her thin. Indeed, the only aspect of Hitler’s life that she found repulsive was his heavy vegetarian diet. When the mashed potatoes with cheese and linseed oil came around, Eva said a firm no.

After Eva, you may be relieved to move on to Barbara Pym—I certainly was—and the warm, jovial relationship with food that she carried on all her life. “Today finished my 4th novel,” she wrote in her diary in 1954. “Typed from 10:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. sustained by in the following order, a cup of milky Nescafe, a gin and french, cold beef, baked potato, tomato-grated cheese, rice pudding and plums.” No, it’s not gastronomy. This is friendship. Food was a steadfast companion that nourished everything in Barbara, especially her creativity. If she so much as glimpsed a well-dressed woman in a café eagerly pouring ketchup over a plate of fish and chips, she came away with a character, then a plot, then a novel. Barbara was aware that modern fiction demanded heroines who were having passionate, tormented affairs, not ordering more pots of tea, but she couldn’t help herself. All she knew how to do was turn out brilliantly witty novels in her unique style, and when critics lost interest in her books, she just kept going. Barbara loved food and she loved love, and most of all she loved the connection between them, which was writing.

Last we meet Helen Gurley Brown, the only woman here whose life extended into the twenty-first century. Helen’s relationship with food, like all her relationships, was dominated by men, or more precisely by what feminist art historians have called “the male gaze.” As the editor of Cosmopolitan she promoted full equality for women, but she did so in a spirit better exemplified by Playboy. Yes, women could be senators, stockbrokers, cabdrivers, and firefighters, but there was no higher calling for any woman than to attract a man. And Helen was adamant on how to attract men: it started with being thin. Rigorous self-denial at the table was the first of her ten commandments for women; in fact, it was all ten of them. The reward would be love and marriage, she promised, and she always displayed her own story as proof. Nevertheless, when she and David Brown were at home in the evening, they ate the way the Roosevelts did—separately.

Pursuing these women through their own writing, through their biographers, through the archives, pouncing on every clue that might help me figure out what they cooked or ate or thought about food, has been just the sort of research I love. It’s like standing in line at the supermarket and peering into the other carts, but with the rare privilege of complete freedom to pry. (Quinoa, miso soup, and four cans of tomato paste? What on earth are you making?) In the archives, happily, there’s no such thing as a rude question. Now that I’ve assembled each of these portraits, however, I can see that even though I’ve always worked within the facts, the facts alone are just the scaffolding. It’s the writer who comes up with the story. And I’m quite sure that none of these women would have written her food story the way I did. This became clear when I began assembling the epigraphs that appear at the top of each chapter. The idea was to introduce every woman with a meal that I found in the records of her life—a meal that summed up for me the complications inherent in her story. I can already hear the six of them objecting to my choices.

Dorothy is wondering a little nervously why I didn’t focus instead on one of those nice gooseberry tarts she used to make.

Rosa is demanding a rewrite: she wants an elegant French entrée that will assure her the place she deserves in gastronomic history.

Eleanor is lecturing me, patiently, on the progressive rationale behind her luncheon menu.

Eva is insulted that I’m describing her life in terms of food instead of, say, showcasing one of her handsome evening gowns.

Barbara, who loved finding out what people ate in real life, can’t imagine why I didn’t use one of her own recipes, especially since there were several among her papers.

Helen alone understands why I chose her particular meal, but she’s making it clear that a better writer would have recognized it as a triumph.

Ladies, I’m listening. What I’ve learned is that everyone’s a critic, even after death, and that any biographer who dares to think she’s getting the last word is sure to end up eating it.