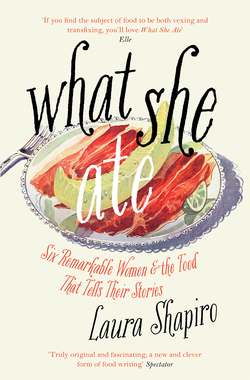

Читать книгу What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories - Laura Shapiro, Laura Shapiro - Страница 9

Rosa Lewis (1867–1952)

Оглавление“Do you know King Edward’s favourite meal? Let me whisper. It was boiled bacon and broad beans. He loved them.”

—Daily Sketch, June 13, 1914

Of all the women in this book, Rosa Lewis should have been the one whose food story was already right there in full view. She was a cook by profession, her meals were famous in her own time, and she worked for herself. Surely she wrote down recipes, drafted menus, scribbled shopping lists, saved receipts from the fishmonger and the greengrocer, and kept notes on the likes and dislikes of her clients. What’s more, she was a public figure, one of the best-known caterers in Edwardian London, sought out by many of the most revered families in the aristocracy, and a favorite of King Edward himself. Newspapers called her “England’s greatest woman chef” and “the greatest woman cook that the world has ever known” and reported on her death and funeral.

Yet the written record is mostly scraps and gaps, gossip and anecdotes. We do have the newspaper stories, as well as a sampling of Rosa’s menus and a few recipes. Occasionally she shared culinary home truths with reporters (“When you cook a quail or a plover, make it taste like a quail or a plover, not like something else”). We know when she bought the Cavendish Hotel on Jermyn Street, we know when she died, and we know the impressive size of her estate—£123,000, the equivalent of around $340,000 at the time, not including the Hepplewhite chairs, Regency tables, freestanding marble staircase, and quantities of rugs and pictures, all from the hotel and sold at auction after her death. But for a woman whose life has inspired five books and The Duchess of Duke Street, a thirty-one-episode public television series, there is surprisingly little that can be verified, apart from some of the food that made her famous. The truth and the legends about Rosa Lewis have been intertwined for so long that it’s impossible to separate them. Which was just the way she liked it.

Plenty of young girls learned to cook professionally in Edwardian England, but Rosa had a more complicated ambition. She wanted great cooking to open the doors of the most exclusive houses in London, and she had her sights on the drawing room as well as the kitchen. It wasn’t about marrying up or discarding her origins; it was about being exactly who she was—“Rosa Lewis, cook!”—whether she was wearing an apron or a Paris gown. There were no role models for such an accomplishment. Auguste Escoffier, the most lionized chef in London, came close, but he was a man, he was French, he ran lavish restaurants, and he hadn’t started out as a Cockney scullery maid.

Most of what has been written about Rosa has borrowed heavily from the first book published about her, which appeared in 1925. The author, an American journalist named Mary Lawton, had heard about Rosa from the theatrical designer Robert Edmond Jones, who urged her to do a story on a woman he called one of the most extraordinary characters in London. “She began life as a scullery maid and became one of the greatest cooks in England—a friend of the King as well as his cook,” he told Lawton—a capsule biography that would always be the best line in Rosa’s résumé. Lawton persuaded the editor of the popular monthly Pictorial Review to give her an assignment, then traveled to London and asked Rosa if she would consent to a series of interviews. Rosa was in her fifties. She had outlived the grand culinary style that made her famous; indeed, she no longer did much cooking of any sort, and the war had done away with the culture of affluence and entertainment in which she had been something of an adored mascot. Here was an opportunity to resurrect a lost world and give life to memories she treasured. She agreed to talk, according to Lawton, and allowed a stenographer to take down every word. Pictorial Review ran a four-part series based on the interviews in the spring of 1924, under the byline “Recorded by Mary Lawton.” A year later the series was published in book form as The Queen of Cooks—And Some Kings (the Story of Rosa Lewis). Written entirely in the first person, the text conveys the impression of a comfortable, loquacious raconteur looking back on a remarkable life and thoroughly enjoying every moment she pulled from the past. (“Once, when I went out to cook a big dinner in a very smart house, one of the maids said—‘Hello! are you one of Mrs. Lewis’ cooks?’ ‘Yes,’ I replied. Then she said—‘How long have you been with her? Does she still drink?’ I said—‘Yes’m, just a little.’ ‘Does she still use bad language?’ ‘Oh, yes, quite a lot,’ I answered.”) Famous names were scattered liberally across the pages—lords and ladies, politicians and actors, a handful of American millionaires—and although Lawton didn’t attempt to re-create Rosa’s Cockney accent, it practically bounces off the page.

As soon as she saw the book, Rosa indignantly called it a “travesty” and threatened to sue. She denied that she had participated in the project. Lawton had come to see her, she acknowledged, and eventually she had agreed to a brief interview, but—“only 20 minutes,” she insisted. She accused Lawton of begging “typists, book-keepers and personal servants” for gossip and chasing down “well-known Americans, who are among my friends,” for material. Maybe so, but this long, rambling narrative, with its reminiscences piled haphazardly one on top of the other, does have the sound of a word-for-word transcript that’s been loosely edited for coherence. The tone of voice is consistent, and the anecdotes have the well-worn patina of tales often told—vague chronology, fuzzy details, vivid moments of triumph. For all her outrage at what she claimed were lies and distortions, moreover, Rosa spent the rest of her life telling the same stories in the same raucous, irreverent style. We don’t know if the stories are true, but I’ve drawn on them here because at least we know that Rosa herself was telling them—a degree of credibility missing from some of the later biographies, which tended to bulk up Lawton’s account with occasional helpings of the authors’ own fantasies.

Rosa Lewis, right, with friends and staff members at the Cavendish Hotel, 1919.

Rosa Ovenden grew up in the village of Leyton, just outside London, the fifth of nine children born to a watchmaker-turned-undertaker. The family was able to keep Rosa in school until she was twelve, but after that she had to work; and for a girl her age the only choice was the lowest rung of domestic service. She became the “general servant” in a nearby household, a job so grim that even Mrs. Beeton, who published the first edition of her soon-to-be-indispensable Book of Household Management in 1859, felt sorry for anyone forced to take such employment. “Her life is a solitary one, and, in some places, her work is never done,” she wrote with a candor unusual in nineteenth-century domestic manuals. “She is also subject to rougher treatment than either the house or kitchen-maid, especially in her earlier career; she starts in life, probably a girl of thirteen, with some small tradesman’s wife as her mistress, just a step above her in the social scale; and although the class contains among them many excellent, kind-hearted women, it also contains some very rough specimens of the feminine gender.” If Rosa’s mistress ran her home according to Mrs. Beeton’s rules for proper domestic service, it’s probable that Rosa started her day at dawn by lighting the fire in the kitchen stove, cleaning the hearth in the dining room, dusting the dining room, cleaning the front hall, cleaning the boots, preparing the family’s breakfast—“if cold meat is to be served, she must always send it to table on a clean dish, and nicely garnished with tufts of parsley”—and then quickly eating her own breakfast so that she could run upstairs and air out the bedrooms while the family was still at table. She then cleaned the house, prepared and served dinner, cleaned up after the meal, ate her own dinner, cleaned the scullery, prepared and served tea, cleaned up after tea, and finally sat down to “a little needlework for herself,” spending two or three hours making and repairing her clothes before bed.

It’s not clear how long Rosa lasted in this situation. She told Lawton that at the age of thirteen—that is, around 1880—she took a job at Sheen House, in Richmond, where the Comte de Paris, an heir to the French throne whose succession had been halted by the revolution of 1848, was living in exile with his family. Hired as a lowly “washer-up” in the comte’s kitchen, she said she began helping his French chef and was soon assisting at dinners served to visiting royalty from all over Europe. The chef put her in charge of the kitchen when he was away, and other family members borrowed her to cook in their various houses in England and in France. “I worked in their family for many years,” she asserted, and gave notice at the end of 1887 only because it had become so difficult for her to share the kitchen with an increasingly jealous French chef. (“For an Englishwoman to try to be their equal—it was impossible for me.”)

Unfortunately this chronology makes no sense. The date of her departure in 1887 can be verified, for Rosa showed Lawton a note written by the comte’s secretary acknowledging Rosa’s decision to leave and offering a reference if she needed one. But records indicate that the comte didn’t move to Sheen House until 1886. Rosa would have had less than two years to transform herself from … a thirteen-year-old scullery maid to a twenty-year-old master chef? One of her biographers, Daphne Fielding, who came to know Rosa in the 1920s, says that she went to work for the comte at sixteen; but that would still put her in Sheen House three years before the comte leased it. (There’s never been a lot of fact-checking when the subject is Rosa, and having tried with little success to track her through libraries and archives, I can understand why.) Nonetheless, there’s truth in the big picture: Rosa did find work in one or more French-run kitchens in the 1880s, which made it possible for her to learn the principles and techniques of the most exalted cuisine in high-society England.

High-society England was what she wanted. Throughout her life she talked jubilantly about her friendships in the aristocracy, and she tried hard to keep a supporting cast of the rich and titled within reach at all times. As a girl working at Sheen House, she told Mary Lawton, “I learnt to think … that it was not a stupid thing to cook. I saw that the aristocracy took an interest in it, and that you came under the notice of someone that really mattered.” Other girls her age chose factory work, but what was a factory girl? “Just one of a number of sausages!” Cooking offered a way to stand out, to win the attention of the sort of people who counted. “My family did not know what Lords or Ladies or Earls or Dukes meant,” she said. “I knew it by being a Cook.”

So it was as a cook that she made her way to the most fashionable dinners in London and the countryside. One of her first employers after Sheen House was Lady Randolph Churchill, the American-born mother of Winston. How she and Rosa connected is unknown, but Rosa’s culinary training at Sheen House would have made her an excellent candidate for a job in a high-class kitchen, and Lady Randolph’s kitchen was among the highest. Her in-laws were the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough; with that flawless credential, as well as the fortune she brought from America, she had become one of the leading hostesses of an obsessively social era. The most important of her dinner guests was the Prince of Wales, who would become King Edward VII after Victoria’s death in 1901. A warm friend and admirer of Lady Randolph’s, rumored to be her lover as well, the prince was also a prodigious eater who genuinely appreciated fine food. Rosa’s cooking pleased him, and from the moment he first complimented one of her dinners, her future was assured. (There are many anecdotes describing this turning point, mostly along the lines of “And the Prince was so impressed by the food that he asked to meet the chef, whereupon a slim young girl dressed in white appeared at the door and hesitantly …” etc., etc.) No matter how the prince and the cook discovered each other, Rosa’s career soon flowered. Society ladies who were distinguished enough to entertain the prince but nervous about whether their kitchens were up to the task hired Rosa for the evening. Other ladies, who couldn’t hope to bring the prince to their tables but aspired to put on luncheons and dinners and late suppers in the best style of the time, hired her as well. Abundant gossip suggesting that Rosa was one of the prince’s many lovers—she never confirmed or denied—did its own part to heighten her desirability as a caterer.

In 1893, just six years into her career as an independent caterer, Rosa married a butler named Excelsior Lewis. She told Lawton she cared nothing for him and married only because her family insisted; but since her parents barely register in her life story apart from this sudden spark of influence, she very likely had other reasons. Describing the wedding to Lawton, she made it sound like a comic song in a music hall: “I went off to church, and we were married. I had nothing on but a common frock. I told the parson to be quick, and get it over with, and he said—‘Why, what a funny woman you are. I’d like to know where you live.’ So we were married, then I threw the ring at him at the church door and left him flat.” But she didn’t leave him flat, not yet. Though she showed no interest at all in children or a conventional domestic life, marriage moved Rosa into a zone of respectability that was very useful to her: with her own home, and a husband attached to her name, she could go from mansion to mansion working wherever she pleased. After the wedding the two of them lived together for nearly a decade while she went right on with her cooking.

Over the next twenty years, Rosa built up her catering until she was managing a staff of six, eight, sometimes twelve women, all uniformed in white, who accompanied her to one wealthy home or another to stage the glamorous luncheons and dinners that were her specialty. “I took full charge,” Rosa told Lawton. “I had complete authority—as though it were my own house, like a general in command.” England had a profligate upper class in the decades preceding World War I, and lavish entertainments were at the center of the London season, which ran from May through July. At a time when a High Court judge was earning £5,000 a year, Rosa said she used to make more than £6,000 during the three-month season alone. She loved talking about her glory years. “I used to go down to Mr. Waldorf Astor’s place, Hever Castle, nearly every week-end … I did dinners for Lady Millicent, Duchess of Sutherland … I did the Ascot Races and the Goodwood Races … Everybody of any note, politicians and famous people, Lords and Ladies, everybody in the aristocracy and in the great London world, had me for their dinners and luncheons.” Sometimes, for families living in the country who wished to entertain in London, she not only prepared the food but rented and decorated an entire house—a service nobody else in the catering business could match, she emphasized. “I furnished the linen and silver and everything and my linen had no names on, silver had no names and my muslin curtains came from the Maison de Blanc in Paris. I would get all the curtains and new carpets from Paris, and then I would go and hire all the best rugs I could find, and all the best furniture I could find, and the whole house would then look as though it were lived in, and not a rented place.” According to Rosa, the other caterers were left in the dust, teeming with jealousy.

Although Edward officially became king in January 1901, his formal coronation with its elaborate ceremonies and entertainments didn’t take place until the summer of 1902. So the spring of coronation year, packed with formal dinners, balls, and house parties, was especially lucrative for Rosa. She would have made a fortune from the supper balls alone: multicourse dinners followed by multicourse late suppers verging into breakfast, and she told Lawton she did twenty-nine of them in six weeks. That same year she learned that the Cavendish Hotel on Jermyn Street, a fashionable enclave near Piccadilly, was up for sale. She promptly bought the place.

The plan was to let her husband run the hotel while she kept on with catering. But Lewis proved inept as a hotel keeper: the hotel deteriorated, guests stopped frequenting it, and the bills went unpaid until he had run up a debt of £5,000. At that point she threw him out of the hotel and out of her life. She called it a divorce, but she may have simply banished him without the trappings of a legal procedure. She told Lawton that once she was rid of him, she took charge of the hotel and was able to restore its former high standard while keeping up the catering business and paying Lewis’s debts in full—all this in sixteen months, by virtue of hard work and scrimping. Rosa was very fond of this story. “So I put my shoulder to the wheel and did everything—only kept a few servants, went to market myself, bought quail at fourpence, and sold them at three shillings, bought my game and vegetables in the open market, loaded them on the wheelbarrow, and pushed the barrow home myself, back to the hotel … I paid that £5,000 on tea and toast, never had anything else to eat, never had a new dress, never even took a bus if I could avoid it. No, I never had a new frock or a stitch of clothing until I had paid every farthing of the £5,000.”

With the Cavendish as her anchor, Rosa had no need any longer for even a symbolic husband: the hotel became her home, her social life, and the center of her business empire. She gave the place the intimacy of a private club, filling it with the pedigreed furniture she found at auction whenever the contents of a great English estate went up for sale. The hotel had no public restaurant at first: the guests dined at graciously arranged tables in their suites, and she took charge of many private parties at the behest of socialites, politicians, and theater people. In the kitchens, a staff of women whom she selected with care and trained herself were cooking for the hotel and also for her catering business, which was busier than ever once Edward was on the throne. As a favored chef of the king, she was hired to prepare formal dinners at the Foreign Office and the Admiralty; and when the kaiser visited England in 1907, spending three weeks at Highcliffe Castle in Dorset, Edward asked Rosa to take charge of all the cooking for his stay. (“One King leads to another, what? … He would eat ham, partridges, very fond of game, and salad, but must always have fruit with everything.”) The Daily Telegraph published an admiring feature on one of the governmental dinners she staged at Downing Street—“Woman Cook’s Triumph”—and her reputation took another leap. “I was at the top of the tree,” she told Lawton, and she stayed at the top until World War I shook the branches.

George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion opened in London in 1914, the last year of Rosa’s reign. The play, which later became the Broadway musical My Fair Lady, has an obvious overlap with Rosa’s story—so obvious that a bit of gossip flutters through a scene in the television series The Duchess of Duke Street to the effect that Shaw based the character of Eliza Doolittle on Rosa. Perhaps, but the differences were in many ways more striking than the overlap. In the play, the Cockney flower seller Eliza Doolittle decides that in order to get ahead in life, she has to get rid of her accent and learn to speak like a lady. She goes to Henry Higgins, a professor of phonetics, who takes her on as an experiment: can he transform this guttersnipe into someone who can pass as a duchess? Eliza is coached in speech, dress, and deportment; and then Higgins introduces her to society—first at an afternoon garden party and later at a dinner party followed by the opera. Eliza conducts herself perfectly everywhere, never revealing a trace of her origins, and not a soul doubts that she belongs among the well-born.

It’s tempting to think of Rosa sitting in the audience on opening night. By her own account she was a close friend of the star, the renowned actress Mrs. Patrick Campbell, although “Mrs. Pat” ran off with Lady Randolph’s second husband that same year, which would have tested Rosa’s loyalty since she adored Lady Randolph. At any rate, if Rosa saw the play, she certainly would have deemed herself a greater success than Eliza, whose despairing cry “What is to become of me? What is to become of me?” rings out during the fourth act. After her triumph in society, Eliza realizes that she has been successfully uprooted but now belongs nowhere. She can’t go back to selling flowers in the street, and since she has neither the money nor the family associated with her new class identity, she can’t see a path forward. In the play, Shaw deliberately left her future vague.

Rosa would have found the whole quandary pathetic. She had conducted her own climb up the ladder very differently, and with a different goal in mind. It was as Rosa herself, Cockney born and kitchen raised, that she demanded to be made welcome in the highest ranks of society—defiantly flaunting her Cockney accent all the way. Back when she was a young servant in the household of the Comte de Paris, she had developed a passion she would nurture for the rest of her life—not for a man, but for an entire class, starting with the comte’s family. “I was overwhelmed with admiration for them,” she told Lawton. He was “marvellous,” his wife “the most interesting woman in the world,” their marriage “the most perfect match in the world.” She had no such language of superlatives for her first employers, an undistinguished family at 3 Myrtle Villas in Leyton, but everything that went on at Sheen House entranced her. All the family members used to visit her in the kitchen, she said. “If you had a round back, when the Comtesse passed through, she would give you a whack and tell you to stand up straight. She told me to keep my back straight just as she told her daughters—with a whip!” To have been disciplined exactly as if she were a noblewoman’s daughter was still making her proud some forty years later.

Lady Randolph Churchill was a similar paragon in Rosa’s eyes, despite an obvious penchant for awkward marriages. (Randolph reportedly died of syphilis; George Cornwallis-West left her for Mrs. Pat; and Montagu Porch, whom she married at sixty-four, was three years younger than Winston.) “She was one of the most perfect women … that I have ever met,” Rosa declared. Another figure in her personal pantheon was Thomas Lister, Lord Ribblesdale, who lived at the Cavendish for years and became a genuine friend. Ribblesdale was lord-in-waiting to Queen Victoria and also master of the buckhounds, a post that chiefly required him to display the grandeur of British high birth as he led the royal procession at the opening of Ascot. By all accounts he did this superbly. John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Ribblesdale, showing him swathed in the magnificent cape, breeches, and boots of a nobleman ready for a day’s hunting, hangs in the National Gallery. Rosa was devoted to him and treasured her copy of the painting. (In fact, she said it was she who urged him to present the original to the museum.) “Lord Ribblesdale was the most wonderful man in the world,” she told Lawton. “His voice and manner and everything about him was just charming. He was a very, very great gentleman—a great specimen of an English gentleman.”

By contrast, she wanted nothing to do with what she called “boughten” nobility. “I don’t like the people who buy their titles,” she told Lawton. “I don’t like the man who makes sugar or the man who gives a few thousands to a hospital having a title, I only like titles which are inherited.” Back in olden times, she went on, “people used to lie under the table drinking and drive a four-in-hand and go swash-buckling around, but they did those things like gentlemen and aristocrats and on certain occasions only—not every day in the week like the nouveau riche hooligans do now … Now it is all vulgar, because the people who do it are vulgar … They are aping their betters.”

The arrivistes were doing badly what Rosa was determined to do perfectly. Coming of age when she did, in the midst of a long, frantic spree of social mobility generated by the Industrial Revolution, she could see that new money was disrupting many of the verities that had long ruled Britain. People whose parents had never dreamed of such advancement were gaining access to education, opportunity, and wealth; and the most conservative among the old-money classes had to close ranks sternly if they wanted to avoid associating with the wrong sort. Then as now, there was no simple way to define social class in Britain—birth, education, accent, manners, taste, and income all contributed, and only the first of these was immutable. Who belonged? Who didn’t? More nerve-racking still, who might belong next week or next year, given a little luck or the right fiancée? Rosa knew, just as Henry Higgins did, that anybody could slip into the upper ranks by acting the part properly. But she also believed that the true greatness of aristocracy was beyond imitation, a state of grace bestowed only upon the well-bred, and that all others would fall short sooner or later. One of the stories she loved telling about herself was tantamount to her own version of Pygmalion: she described the time she arrived at a country estate to arrange a dinner and decided to go in the front door instead of the back. “I was smartly dressed and very good looking in those days, so the lady of the house was almost kissing my lips when I said—‘Oh, it is only Mrs. Lewis, the cook. I know my way to the kitchen.’ Oh, you should have seen their faces! … Lady Paget or Lady Randolph Churchill would have seen the joke, but these people couldn’t, they not being exactly tip-top. It’s only a thoroughbred that does the right thing instinctively.”

Rosa believed with all her heart that she had won a special place among the thoroughbreds. “Although I was a servant as you might say, and went out and cooked for them, they didn’t regard it so,” she explained, distancing herself from the word “servant” even as she was forced to use it. “They found other things in me than my capacity to cook. They seemed to enjoy being with me, and I have always associated with them on equal terms.” Her rich clients visited her in the kitchen, she often said, and she in turn dropped into their drawing rooms—their dining rooms, too—whenever she felt like it. “And I was always welcome,” she stressed. “I trotted in to see everybody at these dinners.” Sometimes she borrowed a gown from a Bond Street dressmaker, along with gloves and a fan—“dressed myself up like a Duchess and gone to the dinner. Then between the courses I would slip down into the kitchen if anything was going wrong, and sometimes bring up a dish in my own hands—and why not?”

One of the photographs she gave Mary Lawton for the book showed the head cook at the Cavendish, “Mrs. Charlotte,” dressed in a simple but beautifully styled evening gown, with her hair piled high in fashionable waves and puffs. She was posed in an upholstered chair, one hand positioned palm-up on her lap, the other holding a book, her gaze off to the side, her expression slightly nervous and frozen into place. “My cook photographed in evening dress looks as good as anybody—as good as a Duchess,” Rosa declared. The occasion for the picture was the annual ball that Rosa staged for her staff and dozens of other cooks, maids, butlers, and doormen from London establishments. She borrowed clothes from shops and from ladies’ maids who passed along gowns from their employers; and she taught the women how to fix their hair and apply a little powder. She hired musicians, she brought in flowers, she put on a splendid supper. “Then I made all the gentry come to these balls and dance with them,” she said. “I made the gentry wait on them, too.” What she wanted to do, she said, was show these servants “the other side of life.” If they could experience it, they would do a better job providing it for others—“with graciousness.”

Rosa could dress the part, and she had an honorary seat at some of the best tables in town; but she knew very well that a former scullery maid was never going to be accepted as an equal in the highest circles, no matter how cheerily everyone socialized with her. Hence she never tried to pass. Once she went with a party of top-drawer friends to dinner at the Carlton, the finest French restaurant in London. At a table across the room she saw half a dozen gentlemen and a lady (“very ugly”) whom she recognized—they were representatives of Pommery, the champagne house, and quite surprised to see her there. One of them asked, loudly, “Isn’t that Mrs. Lewis, the Cook?” Rosa called back across the room, “Yes, it is Mrs. Lewis. I’ve sold all my cutlets, how are you getting on with your champagne?”

To get a sense of the full force of this remark, it’s crucial to remember that Rosa made a point of announcing her class identity with a flourish every time she opened her mouth. She never discarded her Cockney accent—precisely because she knew as well as Eliza Doolittle that it was the most damning of all the accidents of birth and upbringing that kept a flower seller on the street in rags. There were a good many disreputable accents strewn across England—indeed, only one was safely beyond criticism, and that was the style of speech known in the mid–nineteenth century as “pure and classical parlance” and later as BBC English. But Cockney had no rival as the most widely despised of the incorrect accents. Phonetics experts ruled it ugly, offensive, and “insufferably vulgar,” and women in particular were warned to take strict care of their h’s, for ladylike speech was perceived as the outward manifestation of both status and virtue. Manuals on correct pronunciation were popular among those who hoped to climb the ladder, and it was widely believed that a diligent student could shake off poor habits of speech just as he or she could learn from an etiquette manual not to slurp the soup. Rosa could have cleaned up her accent, but she made a choice to retain the speech she had been raised with and deliberately lavished it with slang and profanity. A barrage of impassioned Cockney became her trademark, and everybody who encountered her received a direct hit. American reporters loved to quote her in full color, with every lurid expression intact. In the British press, however, she was invariably quoted in standard English. It would have been impossible for print to convey the impression of a respectable woman if the reporter had ladled a Cockney accent over everything she said.

To be treated with respect, to be treated exactly as one would treat a lady—despite the apron, despite the accent—was what she demanded of the world. When she chose cooking as her life’s work, she made a point of choosing haute cuisine, the most expensive and socially competitive cooking of its time. If food was going to be her shield and her weapon, she would deploy it at such an exalted level that nobody could look down on her. It was a smart choice for a young cook of that era, because wealthy British families were preoccupied not only with setting a fine table, but with using that table to reflect their own rarefied place in society. If Rosa had indeed been in the audience at Pygmalion, she would have scoffed at Shaw’s decision to send Eliza Doolittle to a garden party to test her skills. What a paltry victory! The truly treacherous social occasion of her time was a formal dinner. Rosa, whose longtime vantage point from behind a full-length apron gave her a perspective that Shaw lacked, would have sent Eliza straightaway to the dining room.

“Nothing more plainly shows the well-bred man than his manners at table,” wrote the anonymous author of How to Dine, or Etiquette of the Dinner Table. “A man may be well dressed, may converse well … but if he is, after all, unrefined, his manners at table will be sure to expose him.” And if his manners passed scrutiny, his conversation might trip him up. One reason a dinner party was “one of the severest tests of good breeding” was that a proper host would have made sure that all his guests came from similar backgrounds. “They need not necessarily be friends, or all of the same absolute rank,” explained Lady Colin Campbell in The Etiquette of Good Society, “but as at a dinner people come into closer contact one with the other than at a dance or any other kind of party, those only should be invited to meet one another who move in the same class or circle.” In other words, an upstart at a garden party could chat for a moment and move on. At a dinner, by contrast, the upstart had to understand all the references that bubbled along in the conversation and even contribute a few. (It may not have occurred to Shaw that there was a more exacting test for Eliza’s initial outing than a garden party. He was a vegetarian and also hated getting dressed up, so he made a point of refusing most invitations to formal meals.)

But Rosa understood what was at stake at the dinner table. She knew why people anxiously studied books like How to Dine, which was published in 1879, around the time she first went out to work. “Soup will constitute the first course, which must be noiselessly sipped from the side of a spoon,” counseled the author. “Fish usually follows soup. It is helped with a silver fork, and eaten with a silver fork, assisted by a piece of bread held in the left hand.” Less than a decade later, “Fish should be eaten with a silver fish knife and fork,” ruled the handbook Manners and Tone of Good Society. “Two forks are not used for eating fish, and one fork and a crust of bread is now an unheard-of way of eating fish in polite society.” Only the cognoscenti could hope to make their way through a fashionable meal flawlessly. When Rosa chose high-class cookery as her future, she was gaining access not only to a cuisine, but to all the social behaviors associated with it. She was learning the secret handshake.

Rosa’s remarkable ascent took place at a time when wealth, fashion, and ambition were making extraordinary demands not only upon manners but upon food, which was constantly radiating signals that confirmed or dispelled the status of the householder. The human appetite itself had to be retrained to accommodate the stress. “No age, since that of Nero, can show such unlimited addiction to food,” recalled Harold Nicolson, the diplomat and writer, who was obliged to attend innumerable weekend house parties during the Edwardian era. Four massive meals a day were the rule, he wrote, with a fifth, slightly less massive, at midnight. The author of Party-Giving on Every Scale, published in the 1880s for the benefit of hosts and hostesses who were rightly nervous about this challenge, set out in detail what guests expected to be served at a top-of-the-line dinner. Two soups, to start, one clear and one thick; and the guests would choose whichever they preferred. Two kinds of fish came next, and again the guests made their choices, although there was an important nuance here—“A guest never eats but of one fish, with the exception of whitebait.” Whitebait, a tiny fish caught in the Thames amid much seasonal acclaim, was so definitively British and celebratory that it was the moral equivalent of a separate course and did not have to compete with the other fish on the menu. Then came at least three entrées, a term that did not yet mean “main course” but suggested more of a side attraction, sometimes called a “made dish.” These could be cutlets, croquettes, fricassees—lighter than a roast or a joint, often in a sauce. One or two “removes” then appeared, substantial roasts of beef, lamb, or ham. If there were two removes, it was decreed that the second must be chicken. Then two rotis, or game dishes, arrived, followed by a slew of the pretty, sometimes fanciful dishes known as entremets. Again, this was a term difficult to translate, but they could include savory preparations such as aspics or oysters au gratin and sweets such as jellies, creams, and sweet soufflés. Vegetables were served at different stages of the meal; often there was a salad course; occasionally there was a respite for ices; and sometimes one or two “piquant savories” of cheese, anchovies, or caviar were offered after the last of the sweet entremets. Finally the table was cleared for dessert, typically an array of fruits, ices, cakes, and preserves. No wonder there was an occasional voice pleading for restraint. “Ample choice, so as to allow for the differences of taste, is necessary, but there should be a limit,” urged Lady Colin Campbell. “The perpetual repetition of ‘No, thank you,’ to the continuous stream of dishes handed to you becomes wearisome.”

Just as wearisome were overlong evenings at the table. During the season many of the rich attended formal dinners nearly every night, often sitting next to the same person each time, since places at the table were assigned strictly according to social rank. Depending on one’s regular dinner partner in the course of a particular season, the meals could drag on with excruciating tedium. King Edward was an especially difficult guest in this regard: he got bored very quickly as course after course plodded along. In the royal household he insisted that dinner last no more than an hour, and the new timetable became fashionable across society, at least as an ideal. Hostesses tried their best to keep the courses moving steadily, though having paid huge sums for truffles, foie gras, imported game, and hothouse fruits, they now found themselves nervously watching out for guests who were enjoying a dish so much they threatened to linger over it. “I still remember my intense annoyance with a very greedy man who complained bitterly that both his favourite fish were being served and that he wished to eat both,” recalled Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan, the American-born wife of the Duke of Marlborough. “I had to keep the service waiting while he consumed first the hot and then the cold, quite unperturbed at the delay he was causing.” Lady Colin Campbell set down the rule: No second helpings of the soup or the fish, ever. Second helpings of the other courses were permissible, but only at a small and forgiving family meal.

It wasn’t easy to navigate a safe route through British haute cuisine: traps for the unwary were set everywhere. Anthony Trollope, that excellent authority on Victorian class anxiety, made a point of identifying it with culinary anxiety in his novel Miss Mackenzie, published in 1865. As novelists so often do, he sent several characters to a dinner party, this one at the home of the heroine’s sister-in-law, Mrs. Mackenzie. Eager to stage the affair properly, she had hired a butler named Mr. Grandairs to supervise the food and service, and chose the increasingly fashionable service à la Russe—the food to be offered in courses rather than set out on the table all at once. Each course was a disaster. The soup, purchased from a shop and laden with Marsala, arrived at the table cold. The fish, “very ragged in its appearance,” was also cold; and the melted butter had become “thick and clotted.” Then came three ornate little entrées—“so fabricated, that all they who attempted to eat of their contents became at once aware that they had got hold of something very nasty.” While these were under way, champagne went around the table but quickly ran out since Mrs. Mackenzie had economized by ordering only one bottle. “After the little dishes there came, of course, a saddle of mutton, and equally of course, a pair of boiled fowls.” These were badly carved, and nobody got any of the sauces since they didn’t appear until the course was nearly finished. “Why tell of the ruin, of the maccaroni, of the fine-coloured pyramids of shaking sweet things which nobody would eat … the ice-puddings flavoured with onions? It was all misery, wretchedness, and degradation.”

And yet, as Trollope emphasized, Mrs. Mackenzie was not trying to better herself with that pretentious dinner. This was not an instance of an upstart aiming at a higher class than she deserved. “Her place in the world was fixed, and she made no contest as to the fixing. She hoped for no great change in the direction of society.” She had staged such a dinner simply because that was how well-bred people were supposed to entertain, and since she didn’t have the money or the experience to do it properly, she had done it badly. At this point Trollope, who had clearly eaten more than his share of misbegotten dinners, broke out of his narrative and addressed his readers directly. Why, oh why, he demanded, couldn’t “the ordinary Englishman” with a middle-class income simply offer his friends a little fish and a leg of mutton?

But such a familiar, comfortable solution was inconceivable for Mrs. Mackenzie, and for hosts and hostesses far more sophisticated than she was. Everyone knew that it was the French who occupied the highest realms of cuisine, while the very notion of traditional British cuisine was, as the London chef Charles Elmé Francatelli put it, “a by-word of ridicule.” By the time Rosa began catering, thousands of French chefs were working in British homes, clubs, hotels, and royal palaces, drawn across the English Channel by the opportunities beckoning from a prosperous, bustling nation that was ready to enjoy the unexpected laurel of culinary prestige. Escoffier himself moved to London in 1890 and spent the rest of his career there, in charge of renowned restaurants first at the Savoy Hotel and then at the Carlton. In 1913, when he was president of the London branch of the Ligue des Gourmands, an international association of distinguished French chefs, London had sixty members—the largest branch in the world. Paris came in second, with forty-three. London had become one of the great capitals of French cuisine, and British-born chefs needed French training if they hoped to reach the height of their profession.

Everything about Rosa made her a doomed candidate for advancement in this culinary world. She was British, she lacked formal training in a restaurant kitchen, and worst of all, she was female. The French prejudice against women in professional kitchens had long ago settled over England in a fog of misogyny that wouldn’t lift until decades after her death. For a woman with culinary ambitions there was only the National Training School of Cookery, founded in 1874 to funnel women into careers as cooking teachers and household cooks. Neither of these futures appealed to Rosa, nor was she interested in any of the school’s other diploma programs, which included Housewifery, Needlework, and Laundry. At the time, the most successful woman in the British food world was Agnes Marshall, whose accomplishments would have made her a phenomenon in any age. She ran a cooking school, wrote four successful cookbooks, published a weekly paper called The Table, and sold an extensive line of packaged ingredients, including Marshall’s Curry Powder, Marshall’s Icing Sugar, and Marshall’s Finest Leaf Gelatine. We don’t know whether she and Rosa ever met, or if Rosa saw her as any sort of inspiration, but Rosa chose a very different path. She didn’t teach, she didn’t write, she didn’t sell; she simply cooked, at a professional level that the leaders of her profession refused to recognize. After she bought the Cavendish, she made a point of staffing her kitchens entirely with women and took every opportunity to tell the press why she was doing so: “A good woman cook is better than a man any time.”

Nonetheless, she was careful to work the way every ambitious male cook in London was working: they all kept an eye on the restaurants run by Escoffier. His innovative techniques and recipes, rooted in classic cuisine but refining and refreshing it, constituted the new gold standard for anyone aspiring to work in the best kitchens. There was no escaping his influence, especially after his comprehensive Guide Culinaire, packed with instructions for every dish in his repertoire, was published in French in 1903 and four years later in English. Escoffier’s best-known principle was “Faites simple”—“Simplify”—but even so, he raised the glamour stakes with every major dinner he created. When a group of Englishmen who had won handsomely at Monte Carlo wanted to celebrate at the Savoy, Escoffier created a red-and-gold dinner dripping with excess, its colors carried out in every course from the smoked salmon and pink champagne to the final “Mousse de Curaçao,” which was covered with strawberries and displayed inside an ice sculpture modeled after the hill of Monte Carlo and decorated with a string of red lights. (Only a chicken stuffed with truffles forced the chef to depart, briefly, from the color scheme.) “M. Escoffier holds that things which are beautiful to the taste should be fair to the eye,” wrote Nathaniel Newnham-Davis, the most prominent restaurant reviewer of the day. He singled out a dessert he called “typical” of the great chef’s work: “Baisers de Vierge,” or “Virgin’s Kisses”—“twin meringues, the cream perfumed with vanilla and holding crystallised white rose leaves and white violets. Over each pair of meringues is a veil of spun sugar.”

Rosa was acquainted with Escoffier; in fact, she called him “one of the few Frenchmen I ever had any respect for,” which suggests that Escoffier did her the honor of treating her as a professional equal—unlike the other French chefs in town, who would have regarded her with the undisguised contempt they had for all female cooks except their mothers. But what she valued in Escoffier’s work, or perhaps learned in the kitchen of the Comte de Paris, wasn’t so much the color schemes and the spun sugar; it was a very French fixation on ingredients. Quality began with the raw materials, Escoffier emphasized in the Guide Culinaire, and whenever interviewers asked Rosa how she cooked, she liked to tell them how she shopped. “I did the buying myself for all those dinners,” she told Lawton. “I selected everything … I would quarrel with every tradesman in the town … And I would turn over sometimes sixteen legs of mutton until I got just the right one … And I used in those days to go to Covent Garden Market and pick out all my own fruit and game, and wheel it back on a barrow myself.” She bought hundreds of quail at a time, scrutinizing each one; and although even Escoffier approved of buying turtle soup ready-made from a reputable source, Rosa purchased live turtles, killed them, and made the soup from scratch. Once, choosing the woodcocks for a Foreign Office dinner at a time when the game birds were scarce, she stayed in the shop while each one was plucked and trussed, to make sure not a single inferior bird was slipped into the order. “Whatever I got, I paid the top price, but had the best there was,” she told Lawton.

Rosa didn’t consider her habits extravagant, she considered them essential. No steps in cooking were unimportant; every contribution from every ingredient mattered. “What I have always done (which no other cook ever does) is to cook the potatoes, and the beans, and the asparagus myself,” she told Lawton. “I do not give these to the charwoman or the scullery maid—or a person without brains.” The potatoes were treated “just the same as if they were gold.” And when she had gold, she let it shine unadorned. One of her specialties, the essence of understated luxury, was a whole truffle, boiled in champagne or Madeira and served in a napkin, one truffle per guest. King Edward was fond of this dish, she told a reporter from The New York Times: he hated being served truffles all cut up into little pieces.

The few existing menus that can be attributed to Rosa are all written in French, and to read them is to envision one classic dish after another parading down the runway: Consommé Princesse, Médaillons de Soles à la Joinville, Suprêmes de Volaille à la Maréchale, Selle d’Agneau à la Chivry. But despite the high-style dinners she turned out for the most impressive names in Britain, she was never invited to join her male colleagues in the Ligue des Gourmands. She wasn’t even invited to join her male colleagues in the Réunion des Gastronomes, a dining club for the owners and managers of London’s leading hotels and restaurants, despite the fact that she owned the Cavendish. This snub from Britain’s French establishment may have been one reason why she refused to swoon over the ineffable glories of French cuisine when she was interviewed. She wouldn’t even admit that French cooking was superior to all other cooking the world had ever known, which was the mildest form of appreciation acceptable in her profession. “Good cooking really came from France,” she conceded, but she made it clear that the French had outlived their own success. “A Frenchman couldn’t make a simple quail pudding, for instance. He would not think it was right. He would want to chop it all up and mess it all over with something.” She thought the French used too much wine in cooking and that they overdid garlic: “You don’t want to know it’s there,” she protested. “When you use it as the French do, it kills the taste of what you are eating.” If you’re cooking for the English palate, she emphasized, beef should taste like beef and mutton should taste like mutton—a degree of simplicity she felt the French would never stand for. “And I don’t like anything to look like something else, either—I don’t believe in covering anything just to change it. If it is a sole, I don’t like it all curled up like a lobster—let it remain in its proper shape. Messing things up, is like putting a silk patch on a leather apron—unnecessary and stupid.”

At the same time, however, she acknowledged that a great deal of British cooking was terrible, and she had very specific advice on that subject for home cooks. “Englishwomen seem to be decided on ‘killing’ taste!” she exclaimed. “If the average Englishwoman would only braise her meat, instead of doing so much roasting in her little oven! She ought to braise her vegetables with the meat, in the same pot. It would give better results, and it would save considerable expense.” And, she added, they would not have to keep buying “sundry bottles of sauces, which are always expensive.” But the problem, as she saw it, was the low status of cookery in Britain, not some grim national predilection for overboiling vegetables. “To cook, to a Frenchman