Читать книгу What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories - Laura Shapiro, Laura Shapiro - Страница 8

Dorothy Wordsworth (1771–1855)

ОглавлениеDined on black puddings.

—Diary, January 13, 1829

Ever since the publication of the Grasmere Journal, a luminous record of some three years spent keeping house for her brother William in one of the loveliest regions of England, Dorothy Wordsworth has been a cherished figure in the history of Romantic poetry. As a person separate from her famous brother, however, she’s been notoriously difficult to assess. Here was a smart, spirited, well-read woman who threw herself into a life of ardent service to her brother—so ardent she came to resemble one of those present-day political wives whose gaze is permanently fixed on a godlike husband. Then William married, and Dorothy withdrew any claim on his heart except the appropriate one of a sister. Yet she passed out cold on his wedding day, and her profound distress on that tumultuous morning leaps from the Journal like a frightened animal. Scholars have been wondering for years what to make of it.

There have been countless warring interpretations of the Grasmere Journal and of Dorothy’s life. Was she as happy as a robin in the sunshine of family love? Or was she tormented by incestuous passion for William? Does the Journal prove, tragically, that she might have become a great writer if she hadn’t dedicated herself to William and then his family? Or does the Journal prove, triumphantly, that she became a great writer anyway, working within the modest scope available to her? It’s a murky life with an uncertain moral, but it’s also a life that beautifully demonstrates the way food speaks up even when a very private, very conflicted woman prefers to say nothing.

As I noted in the introduction, it was Dorothy’s encounter with a dinner of black pudding that prompted me to start my search for the food stories in women’s lives. But it was her writing—the spark in her perceptions, the great washes of emotion, the pleasure she took in the mundane—that made it clear why she belonged in this book, indeed right at its front door. By virtue of her wide-open senses and a passion to record, she was creating a perfect context for the idea of culinary biography. To be sure, she kept a great deal of herself hidden even when she was being effusive, and it’s impossible to know how much of her own silent editing went into her journals and letters. Thomas De Quincey, who met her at Dove Cottage in 1807, five years after William’s marriage, was struck by her eyes—“wild and startling”—but said she seemed nervous in company and spoke with a slight stammer. He attributed this to what he called “self-conflict”—an ongoing struggle between her instinctive intelligence and the sense of social propriety that quickly clamped down on it.

I thought about De Quincey’s reaction to Dorothy when I came across a letter she had written thirteen years before they met. Dove Cottage, her journals, William’s marriage—all of it was still ahead. Here was Dorothy at the very beginning, a twenty-two-year-old woman who had fled convention to seize her own future in a blaze of love and poetry. I’ve gone back to that letter many times in the course of pondering Dorothy and her well-kept secrets, and I’m introducing it now, at the outset of her story, because I can’t imagine a stammer in this prose. She was writing in a powerful, deliberate voice quite different from the more impressionistic Grasmere Journal. Dorothy wanted to be understood in this document. It was her declaration of independence. And she chose the language of food.

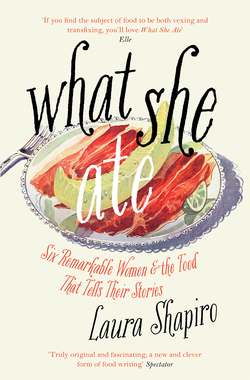

A miniature portrait by an unknown artist showing Dorothy Wordsworth as a young woman.

It was the spring of 1794, and she and William had embarked on one of those arduous, exhilarating walks across country that he loved and Dorothy was just discovering. After years spent apart and months of secret plotting—secret for reasons that will be clear in a moment—the two of them had finally managed to meet, and they were determined to live together as soon as they could assemble some kind of home. Now they were tramping side by side in rain and mud, with Dorothy in bliss at every step. They passed Grasmere, where years later they would settle, and then stopped to visit friends in a mountainside farmhouse overlooking the town of Keswick. There, gazing at a landscape so spectacular she exclaimed that it was “impossible to describe its grandeur,” she received a letter from an aunt she particularly disliked, scolding her for “rambling about the country on foot” in the face of dreadful but unmentionable risks.

She didn’t have to spell out the dangers; Dorothy knew what she meant. During a recent stay in France, William had had an affair with a Frenchwoman and fathered a baby girl. Now he was in disgrace with his family, and nobody considered him a fit companion for his maiden sister—nobody, that is, but Dorothy herself. She had been stunned by the news, but a conflict between conventional morality and the actions of her brother was no conflict at all; her loyalty never wavered. She even pulled together her French and took over the necessary correspondence with his ex-mistress. “I consider the character and virtues of my brother as a sufficient protection,” she told her aunt coolly, and she added that spending time with William was turning out to be a fine way to expand her education. “I have regained all the knowledge I had of the French language some years ago.” Her aunt would not have missed the subtext.

But when she picked up her pen to compose this rejoinder, the first thing Dorothy wanted to establish—even before she launched into her defense of William—was what she was eating. “I drink no tea … my supper and breakfast are of bread and milk and my dinner chiefly of potatoes by choice,” she wrote. It was a diet practically biblical in its simplicity, a perfect stand-in for the dignity of her new commitment. Dorothy maintained strong family ties all her life, but the food of this trek—inscribed in the letter as if it were a placard to be carried overhead—proclaimed her allegiance. She was William’s sister, and it was not just a relationship, it was a calling. She would live as she chose.

The Grasmere Journal is full of food; in fact it’s so voluble on the subject that Dorothy has gained a culinary reputation as well as a literary one. Today, when tourists visit the Wordsworth home that’s come to be known as Dove Cottage, they can see where Dorothy kneaded bread and rolled out pie dough; they can envision the large open fireplace with pots and pans hanging above it (the space is now occupied by a Victorian-era range); they can go into the garden and imagine her gathering broccoli, potatoes, radishes, and spinach. Afterward they can wander through Grasmere and stop at the very shop, more or less, where Dorothy went on a cold Sunday looking for the “thick” gingerbread that William preferred.

Unfortunately for culinary sleuths, however, the trail grows cold here. Apart from the Grasmere Journal, surprisingly little in Dorothy’s extensive written archive—letters, travel journals, more diaries—touches on what she cooked or ate. There are enough scattered passages, especially in her travel writing, to remind us that she was in the habit of paying attention to food. But only during the Grasmere Journal years did she make a point of writing about it regularly. At first glance, then, her food story seems to begin and end in those pages. But if you look more closely, and take into account some of her later journals, which have never been published, it turns out that Dove Cottage gives us only the first act of her food story. There was a second act, which took place twenty-five years later in a distant village called Whitwick; and a third, back in the Lake District, during which she gradually, sometimes cheerfully, lost her mind.

Dove Cottage was a whitewashed house on the busy road between Ambleside and Keswick, a cluster of six dark rooms that were cold and nearly empty when Dorothy and William moved in just before Christmas of 1799. He was twenty-nine, burning to be a great poet; she was a year younger and burning to help him. They examined the place as best they could without much light. The main sitting space downstairs lacked a proper ceiling—it was merely the floorboards of the room above—and the room they thought to use as an upstairs sitting space filled with smoke as soon as they tried to light a fire. Privacy was going to be impossible; the slightest noise bounded from room to room. Dorothy had never seen inside the house before she walked through the door, but she had been dreaming for years about finding a simple dwelling where she could make a home for William. She used to furnish it in her mind; sometimes she set the table for tea and planned what they would talk about. Now she knew exactly what she was looking at: here was paradise.

And it was, but there’s always a serpent. This one bore the much-loved face of a family friend from Yorkshire named Mary Hutchinson. She arrived for a visit two months after they moved in, stayed five weeks, and by the time she departed William knew he was in love with her. In the middle of May he set out on a walk to her home in Yorkshire, taking his brother John with him. Dorothy, who normally relished these marathon treks across country, stayed back this time: she didn’t want to be there when William proposed. On the day he left, her emotions were on such a rampage she burst into tears the moment he was out of sight; and that evening she opened a notebook.

May 14 1800. Wm & John set off into Yorkshire after dinner at 1/2 past 2 o’clock—cold pork in their pockets. I left them at the turning of the Low-wood bay under the trees. My heart was so full that I could hardly speak to W when I gave him a farewell kiss.

She cried for a long time, she wrote, and then went out for a chilly walk by the shore of the lake, which looked “dull and melancholy.” She described the berries and wildflowers she had seen, and she named them. She remarked on the stirring views, she said she had encountered a blind man “driving a very large beautiful Bull & a cow,” and she recalled that she kept stopping to sit down despite the cold. Her eyes had always been sharp, and she had an artist’s instinct for focus; now she would put those gifts to work. “I resolved to write a journal of the time till W & J return, & I set about keeping my resolve because I will not quarrel with myself, & because I shall give Wm Pleasure by it when he comes home again.”

“I will not quarrel with myself.” This vow set the tone, not only for what became the Grasmere Journal, but for the way Dorothy would live from that day on. Long ago she had chosen her future without hesitation: she would be William’s sister, the word “sister” going round and round in her imagination until it blossomed into the glory of a life’s work. She would care for him, cook for him, and be the handmaiden to his poetry. Now, caught up in the trauma of William’s departure, she returned to that commitment and strengthened it: she would permit no flicker of dissatisfaction, unease, or resentment. She knew precisely the degree of happiness she could expect, and she was determined to want no more. William was going to marry, she told herself; his bride would join their household, and Dorothy would give her whole heart to the new configuration—she would, she would, she would. “Arrived at home with a bad head-ache … Oh! that I had a letter from William!”

Writing the journal, which she kept on doing even after her brothers returned from Gallow Hill, was what sustained her during the two and a half years of William’s engagement. All day she gathered up impressions as greedily as a bird pecking about in a newly planted field. Then she opened her notebook and filled page after page with her quick scrawl, describing the crows and ravens, the colors of the lake, the twigs and catkins and clouds and moonlight. She recorded the walks she and William took, their visitors, their illnesses, their quiet evenings, their work in the garden and orchard. And, continuing as she had started with her very first sentence, she wrote about food. Assembling the ingredients and preparing their simple meals was a process that went on continually, and it comes up in these pages over and over like the gently recurring rhymes in a sonnet. She picked peas from the garden, she took apples from the orchard. Their neighbors brought them gooseberries and she turned out pies and tarts and puddings. She bought bacon from another neighbor and gingerbread from the blind man down the street. They caught fish from the lake. She baked bread, she made broth, she bottled rum, she boiled eggs. After years in which her letters and journals said little about food, now it’s everywhere.

Why this sudden attention to their meals? They hardly constituted a novelty: Dorothy had been cooking for William for years. But the notes on food served a different purpose from the other jottings in her journal. When she wrote about the clouds and flowers, the beggars and the gypsies, she was writing for William. She liked to feel that she was his companion, perhaps his inspiration, anytime he might need a bit of support in the lonely work of writing poetry. Her observations on the world around them were there for him to use as he wished. The notes on food, by contrast, spoke directly to Dorothy herself. They reminded her, though she was hardly in danger of forgetting, that everything about Dove Cottage mattered. It was all sacred. She had eaten gooseberry tarts before living in Dove Cottage and she would eat them afterward, but to eat them there was to feed on the very time, the very place, the very love that sustained her.

Cooking, moreover, was wifely. Far more than a chore, in Dorothy’s world it was an aspect of identity. Even if a married woman didn’t do the cooking herself, she was judged on her ability to manage the food of the household. Dorothy was no amateur: she had kneaded and chopped and stirred in many kitchens before she began preparing meals in Dove Cottage. But only now did she seem intent on keeping a written record of how she fed William and their guests, as if to shore up her right to a role she wouldn’t dream of claiming openly.

More than two centuries later, it’s impossible to gauge the quality of Dorothy’s cooking. We’ll never know, alas, whether William used to get up from the table hungry and go out hoping to find a couple of fallen apples in the orchard. Dorothy’s habit of jotting down only cursory notes about the food makes it difficult to analyze the success of her efforts. But inadequate cooks generally know all too well how inadequate they are, especially if they have to cook every day, and there’s nothing in the Journal to suggest that Dorothy lacked confidence in the kitchen. On the contrary, those brief, habitual notations sound as though she accomplished her cooking with practiced efficiency. If she suspected that William didn’t like what she was serving, she would have noticed—he was the object of her intense daily scrutiny—and the anxiety would have pursued her from page to page the way she was pursued by her various illnesses and, occasionally, “my saddest thoughts.”

What we do know about the food of paradise is, first of all, that it was practical. She and William were trying to live as stringently as possible on their small income, and she was accustomed to setting a thrifty table. In the morning they liked a bowl of mutton broth, with bread and butter. For dinner, the most substantial meal of the day, there was often a savory pie filled with veal, rabbit, mutton, giblets, or leftovers. Supper was pretty casual—broth again, or else they just ate whatever appealed to them. One evening that meant tapioca for Dorothy, an egg for Mary, and cold mutton for William.

But there was something wonderfully idiosyncratic about the way they approached mealtime itself. She and William arranged their days exactly as they pleased, and meals took place when they felt like eating them. Nobody was ever dragged in from a beautiful lakeside ramble merely because it was the proper hour for tea. One day she stayed in bed, just because she wanted to, until one p.m.; then she went down to breakfast. Dinner was understood to be a midday event, but in actuality it wandered across the afternoon, sometimes happening as late as five p.m. Tea and supper had to fit into whatever time was left before bed. And if a meal disappeared entirely, nobody seems to have missed it. “We had ate up the cold turkey before we walked so we cooked no dinner,” she reports. On another occasion, “We got no dinner, but Gooseberry pie to our tea.” Home cooking in this era meant that somebody was going to be home, cooking, much of the time; and Dorothy noted more than once that she stayed behind at the oven while others went outdoors. But she wouldn’t allow the steady march of mealtimes to exert any more control over the day than necessary.

What springs most vividly from Dorothy’s food writing is her tone of voice. If the words themselves tended to be dispassionate, there was a glow about them that belied their brevity. “Writing” is almost the wrong term for what she was doing; it seems too effortful. Whenever a pie or a roast or a bag of peas from the garden rose to her consciousness, she simply dropped the image into place among the rest of the day’s incidents, as if she were adding a tiny square of marble to a boundless mosaic of the quotidian.

Wm was composing all the morning—I shelled peas, gathered beans, & worked in the garden till 1/2 past 12 then walked with William in the wood.

Coleridge obliged to go to bed after tea. John & I followed Wm up the hill & then returned to go to Mr Simpsons—we borrowed some bottles for bottling rum. The evening somewhat frosty & grey but very pleasant. I broiled Coleridge a mutton chop which he ate in bed.

I baked pies & bread. Mary wrote out the Tales from Chaucer for Coleridge. William worked at The Ruined Cottage & made himself very ill. I went to bed without dinner, he went to the other bed—we both slept & Mary lay on the Rug before the Fire.

Priscilla drank tea with us—we all walked to Ambleside—a pleasant moonlight evening but not clear. Supped upon a hare—it came on a terrible evening hail & wind & cold & rain.

We had Mr Clarkson’s turkey for dinner, the night before we had broiled the gizzard & some mutton & made a nice piece of cookery for Wms supper.

We had pork to dinner sent us by Mrs Simpson. William still poorly—we made up a good fire after dinner, & William brought his Mattrass out, & lay down on the floor I read to him the life of Ben Johnson & some short Poems of his which were too interesting for him, & would not let him go to sleep.

I made bread & a wee Rhubarb Tart & batter pudding for William. We sate in the orchard after dinner William finished his poem on Going for Mary. I wrote it out—I wrote to Mary H, having received a letter from her in the evening.

I threw him the cloak out of the window the moon overcast, he sate a few minutes in the orchard came in sleepy, & hurried to bed—I carried him his bread & butter.

Cooking, for Dorothy, was inextricable from her life with William: to serve him food was to reinforce all the emotions that bound them. We can almost feel the way the air around them takes on color and sensibility when she sets down the bread and butter or gazes at him as he sits over his bowl of broth. Food transforms the two of them, at least in Dorothy’s mind, to a single glowing entity. Once, when he was away from Grasmere for a few days, she tried frantically to fend off despair by throwing herself into housework, working in the garden, and sending herself on long walks. It was difficult for her to believe in the relationship unless they were together, and the symbol of their shared presence was always food. “Oh the darling! here is one of his bitten apples! I can hardly find it in my heart to throw it into the fire.” On that occasion he returned a day earlier than she expected—“How glad I was”—and she gave him a beefsteak while they sat at the table, “talking & happy.”

Thursday, July 8, 1802, was Dorothy’s last day in paradise. She spent much of it copying out 280 lines of William’s recent work on “The Pedlar,” and in the evening the two of them went out to gaze at the moon. “There was a sky-like white brightness on the Lake. The Wyke Cottage Light at the foot of Silver How. Glowworms out, but not so numerous as last night—O beautiful place!” The next morning they embarked on a three-month journey that would culminate in Yorkshire, where Mary was arranging the wedding. Dorothy scribbled frantically in her journal as long as she could, recording each blessed sight around her. Everything would be there when the three of them returned, but everything would be different; this was a painful good-bye. “The horse is come Friday morning, so I must give over. William is eating his Broth—I must prepare to go—The Swallows I must leave them the well the garden the Roses all—Dear creatures!! they sang last night after I was in bed—seemed to be singing to one another, just before they settled to rest for the night. Well I must go—Farewell.—”

The Grasmere Journal was discreet on many topics, but when she wrote about the wedding, Dorothy tore her heart open. She and William arrived ten days before the ceremony was scheduled to take place. Dorothy took note of the garden, with its asters and sweet peas, and reported, not very convincingly, “I looked at everything with tranquillity & happiness.” The next day she fell sick and remained sick right up until the morning of the wedding when, she wrote, she woke up feeling “fresh & well.” Just before he left for the church, William came upstairs to see her. “I gave him the wedding ring—with how deep a blessing! I took it from my forefinger where I had worn it the whole of the night before—he slipped it again onto my finger and blessed me fervently.” There is some debate about Dorothy’s exact wording here. In her definitive edition of the Grasmere Journal, the Wordsworth scholar Pamela Woof points out that the wedding-ring passage has been heavily inked over, probably by Dorothy. Examined under infrared light the words are fairly legible, and Woof believes that instead of “and blessed me fervently” Dorothy may have written “as I blessed the ring softly.”

Fervently, or perhaps not, then, William went off to the ceremony, while Dorothy stayed behind in her room, fighting off her agitation. “I kept myself as quiet as I could, but when I saw the two men running up the walk, coming to tell us it was over, I could stand it no longer & threw myself on the bed where I lay in stillness, neither hearing or seeing anything.” Mary’s sister, who had been downstairs preparing the wedding breakfast, came up to tell her that the newlyweds were approaching the house, and Dorothy swam back to consciousness. “I moved I knew not how straight forward, faster than my strength could carry me till I met my beloved William & fell upon his bosom.” With the help of one of Mary’s brothers, William got Dorothy back into the house, “& there I stayed to welcome my dear Mary.”

After breakfast, all three departed on a wedding trip home to Grasmere. Dorothy filled page after page of the Journal with details of their sightseeing—“Dear Mary had never seen a ruined Abbey before except Whitby”—and wrote with passion about how her own heart “melted away” as they neared Grasmere, traveling through a landscape she had first encountered with William three years earlier. Only upon reaching home did she suddenly fall silent. “I cannot describe what I felt, & our dear Mary’s feelings would I dare say not be easy to speak of.”

In the weeks following their return Dorothy recorded several cozy scenes. She and Mary baked cakes and had all the neighbors in for tea; Mary read Chaucer aloud one cold day; the three of them went off on their usual rambles. But Dove Cottage was not an ideal home for newlyweds plus one. Everything was audible everywhere, and William worried that the noises of lovemaking were distressing to Dorothy. She never made so much as an oblique reference to any such tensions, but as the months passed she seemed to lose her zeal for the Journal, and by January she was writing hardly at all. On January 11 she took note of the date—“Again I have neglected to write my Journal”—recognizing how thoroughly she had fallen away from the practice of daily observation and note taking. From that day forward, she resolved, she would write more regularly, and she would even try to improve her handwriting. It was a new year and a new life, she was determined to make the best of both, and she would open a “nice” clean notebook as soon as the current one was full.

It never happened. Less than a week later, she made what would be the last entry in the Grasmere Journal. “Intensely cold,” she began. “Wm had a fancy for some ginger-bread.” She went on to describe how she had bundled up and gone to visit Matthew Newton, the blind man who sold gingerbread from his house. William liked thick pieces of gingerbread, but Matthew Newton had none that day, only the thinner sort, baked in slabs. She decided to make her own instead but couldn’t bring herself to tell this to Matthew and bought sixpence’ worth of the slabs just to be charitable. The next day, while she was baking, his wife appeared at the door—she had managed to obtain a supply of thick gingerbread. Dorothy felt obliged to buy some, despite the fact that her own was under way, and took two pennies’ worth. She always enjoyed telling stories about their encounters with the locals, and this one had a mix of generosity and misunderstanding that appealed to her. She also liked what Matthew Newton said about trying to obtain more thick gingerbread for her and transcribed his exact phrase: “‘We’ll endeavour to get some.’” The next day she opened the notebook and started to write the date—Monday, January 17—but something distracted her and she put down her pen even before finishing the word. The Journal ends, disconcertingly, with “Monda.”

Dorothy continued cooking, of course, even when she wasn’t writing about it. But the emotional ingredients that went into each meal changed, now that she was no longer the only woman who broiled a steak for William or gathered the scraps of leftover dough to make him a wee tart. The domestic center of gravity in Dove Cottage shifted to Mary. Talented cook, efficient housekeeper, diligent copier of William’s drafts—she could do everything Dorothy was doing and quickly topped her maiden sister-in-law by becoming a mother. John was born eight months after the wedding, Dora a year later, then Thomas, Catharine, and finally William Jr.

Now we come to the second act of Dorothy’s food story, which unfolds during the winter of 1828–1829. By this time she had been the all-purpose spinster in the Wordsworth family for a quarter century, and what was once a hectic round of domestic responsibilities had largely disappeared. William had become prosperous, and the family was living in one of the grandest houses in the area: Rydal Mount, just down the road from Grasmere. Servants took care of the spacious, well-appointed rooms; there was a full-time cook; the children had grown up. At fifty-six, Dorothy was as energetic as ever, but she was no longer crucial to the smooth running of the household, and when she spied a sudden opportunity to be useful again, she snatched it. Her favorite nephew, John Wordsworth, was about to start his first job in the church: he was going to be the curate in a poor Leicestershire village called Whitwick. William couldn’t hear the name without a groan—“There are not many places with fewer attractions or recommendations than Whitwick”—but Dorothy was elated. She would spend the winter there, a “fireside companion” to brighten his home and make the evenings less lonely. It would be Dove Cottage all over again. She wouldn’t have William across from her at the table, but she would have his eldest son, a perfectly good surrogate. John even had trouble with his eyes, as William did, and couldn’t read very long by candlelight. He needed help, he needed conversation, he needed support in his new endeavor. Dorothy would be indispensable.

According to an early nineteenth-century description of Whitwick, the village was set “in a sharp and cold situation” and had no pleasant features worth noting apart from nearby Charnwood Forest and a trout stream. The main source of employment among the villagers was framework knitting, an industry that produced stockings and was so notorious for low wages that the expression “poor as a stockinger” had been a familiar one for decades. The work was done on huge knitting machines, which families kept in their cottages, running them all day and, if they could afford the candles, into the night. John’s parish also included the neighboring village of Swanington, which had been given over to coal mining for the last two hundred years. Poverty and a grim physical landscape were the most prominent features of Dorothy’s new surroundings.

A handful of Dorothy’s letters survive from the winter of 1828–1829; but more important, she was also keeping a diary. She had started it four years earlier, an irregular record of her walks, travels, visitors, and household activities, quite different from the expansive, emotional conversation with herself she had carried on in the pages of the Grasmere Journal. This time it was as if she simply wanted to gather up whatever scraps of the day had fallen like dry leaves across her memory. So she remarked on an encounter with a villager, an arresting view, a round of laundry, a visit to a neighbor. Her style was nondescript, the content was irrelevant to William’s poetry, and to a modern eye her speedy scrawls are barely legible. Hence these later journals have attracted far less attention than her other writing and have never been transcribed or published in full. But thanks to a few scholars, in particular Robert Gittings and Jo Manton, who scrutinized these jottings in the course of preparing their biography of Dorothy, we can start to guess what it was like for Dorothy to live in Whitwick. The version in her diary didn’t always match what she was telling friends in her letters.

Take the weather. “Five weeks have I been here, and not a single rainy day,” she announced to her close friend Jane Marshall right after Christmas. Yet the diary for her second week at Whitwick tells a different story: “A gloomy morning. Slight rain …” “Blustering dark morning—Light Rain …” “Dreary and damp …” “Very slight rain before church—gloomy only …” Or take the habit of vigorous walking that was still important to her. In Whitwick she headed out onto a bare, pitted terrain or followed a road busy with cartloads of coal. “It may be called a good country for walkers,” she told Jane brightly. In the letters she says little about her day-to-day activities; her diary, by contrast, tells us that much of her time went to housework. Cleaning went on constantly, for instance, because of the soot and coal dust in the area. Laundry, too, was more onerous. In the evenings she helped John with his sermons—apparently they were not very stirring—and rarely entertained visitors. But her letters say nothing of drudgery or tedium. Over and over she indicated that she had found the best possible place to be, and that was at John’s side. “I am more useful than I could be anywhere else.”

The blissful certainty that John needed her was the sun that greeted her each morning in Whitwick, no matter the weather. Dorothy’s rose-colored letters from Whitwick were not efforts to hide or disguise reality; on the contrary, they offered a picture closer to her emotional experience than the plain facts in the diary. Jotting down what she did each day reminded her of how she really lived. Then she closed the notebook and surrendered for a while to her heart, which was trying to reassemble Dove Cottage from the unpromising materials around her. But unlike the Grasmere Journal, her Whitwick diary says almost nothing about food, and the absence is noteworthy. No sacred moments over a basin of broth, no tears over a bitten apple. Only on a couple of occasions did something about a meal prompt Dorothy to jot down what they had eaten—and to do so in the diary, her outlet for truth telling.

John’s cook was a woman named Mary Dawson, who had worked for the Wordsworths back at Rydal Mount. Dorothy called her “an honest good creature, much attached to her Family,” but missing from this testimonial was any praise for Mary Dawson’s skill in the kitchen. In fact, she had worked chiefly as a maid until the Wordsworths, eager to replace a terrible Rydal Mount cook, moved Mary Dawson into the position. The family needed a talented cook just then, because Mary Wordsworth was recovering from an illness and could not be persuaded to eat. In order to tempt the invalid, Dorothy had asked Mary Dawson to prepare “all sorts of nice things”—a challenge evidently beyond her, because she, too, was soon replaced. But for John’s purposes, Mary Dawson appeared to be the perfect choice. He was living on a very small salary, and there would be no call for “nice things.” The virtue of Whitwick cuisine would be its economy. As Dorothy put it, “She will be a right frugal housekeeper.”

And so she was, which explains one of the most startling notes on food in any of Dorothy’s journals. She jotted it down on a frosty January day in Whitwick: “Dined on black puddings.”

That’s all she wrote, and it’s possible, of course, that I’m reading too much into it. Perhaps black pudding was a perfectly ordinary dinner for the Wordsworths, one that William, Mary, Dorothy, and the children had eaten happily for years; and on this particular January day Mary Dawson simply continued the tradition. But I don’t think so. Nothing about the nature of black pudding—and nothing about the Wordsworths—suggests that this was the case. I believe Dorothy found it extraordinary to dine on black pudding and that the few words she said about it said everything.

Dorothy made only two remarks about food in the Whitwick diary: this note about black pudding and an earlier note in which she mentioned Christmas dinner. Her birthday was December 25, so Christmas dinner was always doubly festive, and the family typically put her favorite dishes on the menu. This year the celebratory meal was simple but just right, and she scribbled it down: “Rabbit pie & plumb pudding.” She and William had dined constantly on savory meat pies when they were living together, and plum pudding was a holiday icon she had long relished. The Christmas menu, in other words, was a taste of her beloved past. Black pudding was the opposite: it was a taste of Whitwick.

Pretty much everything about black pudding signals that this menu originated not with Dorothy but with Mary Dawson—“our homely Westmoreland housemaid,” as Dorothy called her. It’s true that the Wordsworths ate plenty of pork in all forms, and for a time they even owned pigs. Yet black pudding never appeared anywhere else in Dorothy’s journals; it never showed up in her letters, and there’s no mention of it in the family’s recipe collections. A look at how the dish was made, and the class connotations that were packed into the casings along with the blood and oatmeal, may help to explain why.

Here’s a typical recipe, from Hannah Glasse’s authoritative kitchen bible, The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy, first published in 1747. Before killing your hog, she instructs, boil a peck of groats for half an hour. As soon as the hog is dead, collect two quarts of the warm blood and stir it constantly until it cools. Then stir in the groats and add salt, a mixture of cloves, mace, and nutmeg, and a few chopped herbs. The next day, clean the intestines of the hog and fill them with the blood mixture, adding an abundance of chopped fat as you go. “Fill the skins three parts full, tie the other end, and make your puddings what length you please; prick them with a pin, and put them into a kettle of boiling water. Boil them very softly an hour; then take them out, and lay them on clean straw.”

Plainly, there wasn’t much margin for error. The blood had to be fresh and warm or it would coagulate; the oats had to be fully cooked beforehand so they would be ready at the right moment; the intestines had to be scrubbed absolutely clean, and they couldn’t be overfilled or they might burst. As a vicarage cook, Mary Dawson wouldn’t have made her own black puddings; she would have purchased them, and we don’t know where. What we do know is that she was a penny-pinching housekeeper with no instinct for good food—a terrible combination of character traits for someone buying this particular product. Provenance was key. Like all sausages, a black pudding of unknown origin was suspect by definition. The cookbook author Mary Radcliffe, writing in 1823, advised her readers that they could safely eat the ones offered by respectable farmers and country gentlemen, but not the ones for sale in the butcher shops of London. These, she cautioned, were “so ill manufactured … as to form a food by no means very inviting.”

Cheap and ubiquitous, with a phallic shape irresistible to humorists, black puddings often appeared in the popular press as the favorite food of petty criminals, rascals, serving wenches, fools, and assorted lowlifes. “Merry Andrew,” the archetypal eighteenth-century buffoon, carried a black pudding, and “Moggy,” a dunce of a girl who couldn’t answer the simplest questions of the catechism, angrily pulled a black pudding out of her dress and smacked the parson in the face with it. But by the early nineteenth century more dignified sources were also acknowledging the lowly class standing of black pudding. The author of a Victorian-era glossary of North Country words and expressions called the dish a “savoury and piquant delicacy” but added that it was mostly seen “among the common people of the North.” At the large breakfasts set out for upper-class families, black pudding continued to make an appearance; but eventually the dish lost even its morning cachet. “Black puddings are not bad in their way, but they are not among the things we would make to set before our friends,” ruled Georgiana Hill in The Breakfast Book, published in 1865.

Why, then, did it show up that January day? Dorothy wouldn’t have enjoyed such a meal under any circumstances, for she suffered from what was probably colitis or irritable bowel syndrome and had been reporting painful attacks for years. Black pudding, heavy and notoriously indigestible, would have looked to her like intestinal agony on a plate. And she was the de facto mistress of the house; Mary Dawson would have consulted her on the dinner menu. Dorothy could have raised an objection. She didn’t.

Dorothy didn’t object to anything at Whitwick. She accepted all of it and simply translated her experience into the language she preferred, the language of happiness and satisfaction. She approved of frugal cooking and had done it herself, joyfully, at Dove Cottage, where her simple meals had been woven into the fabric of each day’s blessedness. When she made broth, it was for William’s breakfast; when she broiled a mutton chop, she served it to Coleridge in bed. “Wm & John set off into Yorkshire after dinner at 1/2 past 2 o’clock—cold pork in their pockets,” she wrote on the first page of the Grasmere Journal. It was she who had roasted the pork and wrapped the cold scraps for travel; that’s why she put it in the Journal. The very words bound her together with William. Now she was gazing at her dinner in John’s lonely house and seeing all she had lost. The food was foreign, it belonged nowhere, and neither did she. So she translated it. Like the gloomy weather, black pudding went into the diary undisguised; the words were plain and truthful. But the meal as she chose to taste it was sweet.

Dorothy had been in Whitwick for only a few weeks when John received news that the prospects for his future had brightened. Another opening for a curacy had turned up, this one in Moresby—a more prosperous and appealing town, located on the west coast of England not too far from Grasmere. He accepted the offer gratefully and made plans to move by summer. In this congenial new post, he would have no further need of his aunt’s companionship. Dorothy would stay with him for the rest of the winter, but the fantasy of extending her term of service indefinitely—winter after winter, central to John’s life and first in his heart—was abruptly shut down. As always, she expressed only happiness; but paradise was about to disintegrate once again. Dorothy had arrived in Whitwick in perfect health. As she assured a friend, “I can walk 15 miles as briskly as ever I did in my life.” When she left, she was an invalid.

It’s hard to know what precipitated her collapse that April, but one day, after she had nursed her nephew through a bad week of influenza, Dorothy was seized with intestinal pain and spent two long days in what William described later as “excruciating torture.” This may have been an attack of gallstones or possibly a dramatic worsening of her usual colitis. The family was terrified that she might die. An “obstruction” was removed, and afterward she was so feeble she couldn’t move or speak. Mary sped to Whitwick to take care of her, and slowly she became stronger, but that summer she had a relapse. When she finally returned to Rydal Mount in September, she found that even a two-mile walk was too much for her. Increasingly she felt exhausted and confused. Her symptoms—violent pain in her bowels, nausea and vomiting, and debilitating weakness—were not unfamiliar to her. She had recorded similar attacks from time to time in the Grasmere Journal (much to the displeasure of William Knight, the Journal’s first editor, who didn’t like the bowel references any better than he liked the food references). But after Whitwick, a pattern set in: she would collapse in agony, recuperate and gain a bit of strength, then fall back once more.

The standard treatment for pain was laudanum, a tincture made from opium mixed with wine or brandy. Dorothy had taken it regularly in the past for toothaches. Now she was relying on it for her frequent intestinal attacks, and the worse they became, the more heavily she was dosed. The drug, of course, was addictive; it also affected the brain, and by 1835 Dorothy was showing signs of mental disintegration. Gradually illness stripped her of nearly everything that made her recognizable. Once she had been sharp-minded, vigorous, and perpetually curious, always ready for a trek or a project, always eager for conversation. As her body and mind deteriorated she became trapped ever deeper in what Mary called a “child-like feebleness,” given to outbursts of rage, hilarity, babbling, and profanity. Helpless and homebound, she became the focus of constant worry and round-the-clock nursing. Yet in one way or another, using language when she had it and other means when she didn’t, she continued to tell her food story. In fact, it was all she wanted to talk about.

The third act of Dorothy’s food story takes place during the twenty-six long years of her illness, which among other gifts and heartbreaks left Dorothy with a new body. She had always been thin, even gaunt, but after the onset of her dementia she started complaining of “faintness and hollowness,” as William described it. He said she constantly craved “something to support her.” More and more, that something was food. She wanted to eat, she demanded to eat; her pleas became incessant. For the first time in her life she grew fat, then very fat: it took two people to hold her up if she decided to “walk” by pushing her feet along the floor. She told William she was happy only when she was eating.

But much as she craved food, it was a metaphor for something she craved even more desperately. No, not love—she knew she was loved; William never left her in the slightest doubt about that. One day at Dove Cottage she broke a tooth and realized she was well on the way to losing all of them. “Let that pass,” she wrote calmly in the Grasmere Journal. “I shall be beloved—I want no more.” But in the wake of her first breakdown at Whitwick, she had experienced a novel sensation. As she recuperated, she became aware that her illness had prompted an outpouring of tenderness, sympathy, and worry from numerous friends and family members. She was deeply moved to hear from so many people. For the first time in her life, she was able to bask in the warmth of simultaneous attention from just about everyone she knew. “It drew tears from my eyes to read of your affectionate anxiety concerning me,” she wrote to an old friend. “In fact it is the first time in my life … in which I have had a serious illness, therefore I have never before had an opportunity of knowing how much some distant Friends care about me—Friends abroad—Friends at home—all have been anxious.”

Selfless devotion to others had long been Dorothy’s vocation. She had taken care of William, she had tended to Coleridge, she had helped raise children, she had poured attention on the lonely and the needy, and whenever it seemed that she might run out of work, she managed to find more—until illness opened up another way to live, and she slipped right in. By 1835 she had discovered self-pity. That year William and Mary made a trip to London, leaving Dorothy and their daughter Dora, who was also chronically sick, in the care of the Rydal Mount servants. Dorothy was still able to write in her diary at that point, so we have an account of her reaction; apparently she had begged them not to go. “Wm & Mary left us to go to London. Both in good spirits till the last parting came—when I was overcome. My spirits much depressed … More than I have done I cannot do therefore shall only state my sorrow that our Friendship is so little prized & that they can so easily part from the helpless invalids.” Never in her life had she expressed herself in those terms—“poor me, poor me” was simply not the way she responded to trouble or deprivation. But she was whining now, feeling sorry for herself as assiduously as if she had decided to make up for lost time.

“It will please Aunty if one of you will write to her,—for she often tells us nobody takes notice of her,” Mary reported to a niece, adding, “She has been very cross lately.” Dorothy complained often that she was neglected by her family; she said she was “ill-used” and needed protection, and she begged for signs of affection. The arrival of a birthday gift sent her into cries of delight: “You see, I have good friends who care for me, tho’ you do not,” she declared to a Rydal Mount servant who had been attending her faithfully. When the man of letters Henry Crabb Robinson, an old friend, was planning a Christmas visit to Rydal Mount, William wrote to tell him Dorothy was demanding a present. She fancied a box of the winter apples known as “Norfolk Beefins” and had been asking for them over and over, saying “she was sure if Mr Robinson knew how she longed for them, you would send her some.”

Responding to Dorothy’s pleas and outbursts was a tiring job, and responding to her physical needs was even worse. Dorothy’s symptoms included incontinence and bouts of violent diarrhea, as well as racking pains, chills, fever, and perspiration. She and her bedclothes had to be cleaned up repeatedly. She could not be left alone. Sometimes she moaned, chattered gleefully, or let out a wild shriek; when she was in a fury she struck out wildly at the women caring for her, and on occasion she horrified the family by bursting into profanity. When guests stayed overnight in the house, they had to be given rooms as far as possible from Dorothy’s lest she frighten or unnerve them. Yet there were also periods of clarity when she seemed almost her old self. “If I ask her opinion upon any point of Literature, she answers with all her former acuteness; if I read Milton, or any favourite Author, and pause, she goes on with the passage from memory,” William observed wonderingly. She was able to write a letter occasionally or sit in the garden contentedly. Then suddenly she became a spoiled child again, hurling demands. All year round she insisted on having a fire in her room, saying the warmth was the only thing that made her feel better. In summer her room was so hot nobody else could bear sitting in it, but if the fire was allowed to die down, she went into one of her rages until it was restored to full strength. The ever-sweltering bedroom drove Mary to the edge of her patience. “This is an intolerable experience,” she complained in a rare burst of open frustration. She was thinking in part about the amount of money they were spending on coal in the middle of August.

Physically dependent, mentally beyond responsibility, the object of constant and devoted care, the center of attention whenever she chose—Dorothy in illness was reborn. Even during the periods when she felt relatively strong, she never objected to the restrictions on her activity imposed by the doctor and her family, and she calmly accepted the pampering. “I have been perfectly well since the first week in January—but go on in the invalidish style,” she reported to a friend in April 1830, two years after her initial breakdown in Whitwick. “Such moderation I shall continue for another year … My spirits are not at all affected.”

But of course her spirits were affected. They were transformed. She had entered a realm of greed without guilt, insisting on more heat than anyone else could bear, more attention than her weary caregivers could muster, more gestures of love than she had ever received before. And, incessantly, more food. In all the many pages of her diaries and letters over the years, she rarely mentioned an instance of feeling hungry. Now she was never satisfied. One Christmas Jane sent a gift of freshly killed fowl—a turkey and two chickens—and Mary brought them to show Dorothy. “I wish you could have but seen the joy with which that countenance glistened at the sight of your never-to-be-forgotten present,” Mary wrote later. “Every sensation of irritation, or discomfort vanished, and she stroked and hugged the Turkey upon her knee like an overjoyed and happy child—exulting in, and blessing over and over again her dear, dearest friend … The two beautiful lily white Chicken were next the object of her admiration, and when Dora said it was a pity that such lovely creatures should have been killed, she scouted the regret, saying ‘What would they do for her alive … and she should eat them every bit herself.’”

William fought desperately with her about food. The Dove Cottage days of quietness and harmony over lovingly prepared bowls of broth were long gone. Dorothy was clamoring for all sorts of rich foods, and her anguished brother was terrified to give them to her, certain they would make her “bilious” and bring on another agonizing attack. “I feel my hand-shaking,” he wrote to Robinson after a bout of her screaming and frustration. “I have had so much agitation to-day, in attempting to quiet my poor Sister … She has a great craving for oatmeal porridge principally for the sake of the butter that she eats along with it and butter is sure to bring on a fit of bile sooner or later.”

“I will not quarrel with myself.” Dorothy held firm to her vow for twenty-nine years, but after her collapse at Whitwick she lost control. Everything came out, unseemly and uncensored. From time to time she experienced intervals of remarkable lucidity, writing letters and remembering her favorite poems in a manner that reminded everyone of the person she used to be. “She is … for a short space her own acute self, retains the power over her fine judgment and discrimination—then, at once, relapses,” Mary reported. “But she has no delusions.” Dorothy did retain a grasp of her environment even when her personality disappeared, so in that sense she had no delusions; yet she was meeting the world afresh. She took to singing when she felt like it; she made friends with a bird that flew in her bedroom window. In 1837, amid some of the worst years of her illness, she woke up one day feeling momentarily clearheaded and wrote a letter to her niece Dora. “Wakened from a wilderness of dreams, & rouzed from Fights & Battles, what can I write, do, or think?—To describe the past is impossible—enough to say I am now in my senses & easy in body.” She was in her senses, she was at ease in her body; that was all she could say, and it was enough.

There are different ways to read a life, and Dorothy’s long decline, most often described as tragic, perhaps had moments of triumph as well. Consider, for instance, the image that will serve to conclude her food story—Dorothy in her chair, round and imperious as royalty, demanding porridge so that she could eat the butter.