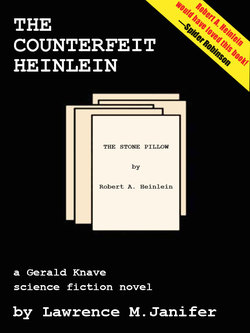

Читать книгу The Counterfeit Heinlein - Laurence M. Janifer - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER NINE

When the Master’s rasp stopped, the place was very quiet. Little Robbin Tress whispered: “Wow. Gee, Master Higsbee—gee, Sir—wow, I wish it were real. I mean I wish it were a real Heinlein story.” And then, dreamily: “Maybe, someplace, it is.”

“It might be so,” the Master said. His voice sounded tired, but no more tired than usual. If asked, he’d have told you, extensively, how worn and ancient he was, and how much the recital had taken out of him. So I didn’t ask.

Robbin offered to help with cleaning up, but the Master knew how I feel about household chores generally and dishwashing in particular, and managed to persuade her that my refusal was serious, and not ill-tempered in the least. We spent a few minutes in reminiscence—Robbin had once been a help about a Fairy Godfrog, of all the damned things, and the Master remembered some odd consulting he’d done for me here and there (and all the reasons why I shouldn’t have had to consult him, but could very well have figured matters out on my own)—and then, with both parties readying graceful goodbyes, it happened again.

This time, the damn nuisance didn’t miss.

Of course, this time he wasn’t shooting at me. In fact, we none of us heard the shot, for which I was and am profoundly grateful; that one sound would have tossed Robbin back five years and more in her own progress, and, which seemed almost as important somehow, would have been the occasion for endless complaining from Master Higsbee.

Six or seven minutes later, we were finishing up goodbye-and-reply routines, of which Robbin had a full set (the Master’s version was of course short and simple) when my phone blipped, and they stood frozen at the door, the way people will, while I went and answered it.

B’russ’r B’dige’s sweet high tenor asked me if I were me, and on getting confirmation gave me the news. I said I would be right the Hell there, hung up, and began to shoo my guests out before I had a chance to think.

Then I stopped shooing them, and instead began telling them what had happened. “That was B’russ’r B’dige. Somebody has just shot Ramsay Leake and knocked him off his tenth-floor balcony. B’russ’r thinks it’s connected. I’m going down to the Leake place—want to come along?”

The Master took one quick look at Robbin Tress. “I think not, Gerald,” he said slowly. “We will have to catch up later—of course you will provide. But Robbin should be home.”

The girl was absolutely crestfallen. She was actually wringing her hands, something I don’t seem to see much. “I’m so sorry, Sir,” she told me earnestly. “But it is a strain, and they tell me I have to be careful about strain. In a little while when I’m better, I won’t have to be so careful maybe, but right now I do, Sir, and I am sorry but I think I do have to go home, if Master Higsbee will help me get there.”

She did have enough spirit left, or something, to bat her eyelids at the Master a little, and stifle a small giggle. To his credit, he let both pass as friends, not even asking for recognition codes.

“Of course,” I said. “I’ll check in with one of you as soon as I can, and as soon as I know anything. But let’s shut up shop in a hurry—I’d like to get there while the scene is still a scene.”

The Master nodded. Robbin was still agreeing we should hurry when he bundled her into their waiting closed car and took off, and by that time I was flagging a passing taxi and giving him directions to VT.

Which was, of course, the name of Ramsay Leake’s modest estate—Leake being a computer-simulations expert. If you don’t recognize the allusion, that’s because it is rather a Classical tag; back before the Clean Slate War, computer people on early comm networks used to speak of RT and VT—Real Time, or life every day, everywhere, and Virtual Time, or life on the comm net. The differences were beginning to be appreciated, apparently, right from the start of comm networking, and Leake had reached back to the ancients for his estate name, as a neat enough challenge to those differences, and one I found instantly admirable. Unfortunately, I couldn’t compliment him on it, not any more.

He was right there—what was left of him. But there wasn’t enough left to compliment—after a ten-story fall, there was barely enough left to recognize. Ravenal has 0.97 Standard gravity, but the 0.03 difference didn’t seem to amount to much in practical terms just then; Leake was just as jellied by the impact as he’d have been if he’d come down somewhere in ancient Oregon, or Uta.

VT had been a ten-story tower, round and rather thin, sticking straight up and surrounded by terrace-railings every two stories from the fourth on up. The word that sprang to mind, out of ancient literature, was “minaret”. A fascinating building, and about one hundred times as imaginative as your average Ravenal structure of any sort at all. Oh, why not—a thousand times. Easily.

B’russ’r was there, too, some distance from the minaret, chatting politely with a police official I’d met briefly, a Detective-Major Hyman Gross. I climbed out of my taxi and ambled over to join them, perhaps thirty feet from the body, where a small army of techs was at work taking photographs, measurements, readings and anything else not nailed down. As I came within earshot, Gross was saying: “I respect your abilities. Hell, anybody respects your abilities, Mr. B’dige. But this isn’t even a large coincidence. Sort of thing that happens all the damn time, I mean to say.”

B’russ’r only nodded at the man patiently.

“It is not the coincidence of the weapon that concerns me,” he said. “It is the coincidence of the occupation—not, I think you will agree, a small matter. My conclusion is a consequence—”

“Of information upload, I know,” I said. “Hello, B’russ’r. Major Gross.”

The Major gave me a stare. For Gross, this was a large undertaking: he had a red round face, even redder up where most of his hair had once been, and big, big eyes that bugged out as far as I’ve ever seen a human being’s. He focused those exopthalmic things on me and said: “You too, Knave? What is this now, a plot? Are you ganging up on me now?” in a wheezy, wine-soaked little baritone.

“Perhaps Knave appreciates the situation,” B’russ’r said.

“I might,” I put in, “if I knew what it was. Leake fell from his tenth-floor balcony. How in the name of the original preSpace Gross do you know he was shot first? The shape he’s in, that ought to take a careful autopsy.”

“The shot was seen and heard,” B’russ’r said. “This time, we have witnesses.”

Gross snorted. “What do you mean, this time?” he said. “If you truly want to tie this death here to the Berigot shootings five years ago, you had a job lot of witnesses then. We all of us did.”

B’russ’r stirred his wings a bit, forth and back. Confusion, and enlightenment—the Berigot equivalent of Aha. “I see,” he said. “There has been a misunderstanding. It is not the shootings I wish to connect, Major Gross. It is the theft.”

“Theft?” Gross said. “And just by the way, Knave, who the Hell is this ‘original preSpace Gross’? Relative of yours? Some long-forgot relative of mine, perhaps?”

B’russ’r nodded a little sidewise at me, and I shrugged. Translated: “Do you mind if I supply the data?” “Not at all, go right ahead.” Berigot are very polite, even a tad ritualistic, about information transfer. Naturally, I suppose.

“The Gross referred to,” he told the Major, “is the author of Modern Criminal Investigation, a much-used police textbook just preSpace. Not only historically noted, but at times still quite helpful; his differentiation of some burned corpses from fight victims remains classic.” He bowed just a trifle. “Not perhaps a subject of study in today’s academies,” he said. “As for the theft—”

He went on to describe, very sketchily, the Heinlein-forgery situation. Gross nodded. “And you believe this death here is connected?” he said at last. “Why? What would connect this Leake with an old manuscript?”

“Leake,” B’russ’r said, “would have helped to fake it. The conclusion is, if not certain, surely irresistible.”

Gross said: “Why would you say irresistible? Why would you come to any conclusion at all, for heaven’s sake? Look, Mr. B’dige, you mention occupations. Well, this Leake was a computer-simulations expert. Whatever your old manuscript might be, it wasn’t a computer simulation. When it was written new, perhaps there were people who didn’t even have computers.”

B’russ’r cleared his throat—something a Beri never does, except to imitate humans. I’d been wondering when he’d get around to it, and now he had. “B’russ’r, please,” he told Gross. “It is true that B’dige is a name. But like most names placed in second position, for Berigot, it is functional, not personal. Simply B’russ’r, please.”

“Not personal?” Gross said.

I nodded sidewise at B’russ’r, and he shrugged back at me. “That second name,” I told Gross, “is a little bit like ‘Teacher,’ say, or ‘Driver’—and a little bit like ‘redhead’ or ‘shorty.’ It describes a function or an attribute of some sort, not a person. The name a Beri uses is his name—the first part. The second part is more of a title, or a nickname—at nay rate, functional, not personal.”

Gross nodded. I have no idea to this day whether he’d got it. But he did say: “Good for it, then: B’russ’r. All right with you?” and B’russ’r nodded very politely.

“Thank you,” he said. “And as for your question—the manuscript was, in a way, a computer simulation. Such a simulation must have been used to create the effect of the forgery; at the detailed level at which it was constructed, there would be no other way.”

I’d had the taxi ride over to think that out, and of course it made sense. Gross hadn’t had either my additional minutes, or B’russ’r’s information upload, and just looked confused.

“Some of the isotope assay checked out,” I said. “And how do you build a pile of paper, and a barrel of ink, that has an isotope percentage match to, say, 1950 instead of 2300? You do it by running the entire molecular makeup through computer simulation, tracking it back in time, and coming up with a simulation giving you just the percentages you need for 1950. Then you make the 1950 recipe into a 1950-plus-350-years recipe—more simulation work—and build the paper from that. Done completely, it would be undetectable, because every isotope assay would check out. Why it wasn’t done completely, we don’t know. Apparently even the forger can’t manage that yet.”

B’russ’r rustled his wings, spreading them open just a bit and then shutting them, two or three times. Applause. “Flawless,” he murmured. I bowed just a trifle.

“There’s a job lot of computer-simulation experts, now,” Gross said. “It’s not as if this Leake person was going to be the only one in the galaxy. Or even the only one in the whole of City Two.”

“The forgery was stolen three nights ago,” B’russ’r said quietly. “Leake was shot dead tonight. This would call for rather a large coincidence.”

Gross snorted again. “Coincidences do happen, B’russ’r,” he said, and B’russ’r nodded, and said just before I could:

“So they do. Connected events also happen. One must learn to distinguish.”

At which point a tall thin woman in a tweed suit bustled up to Gross and said: “We’re done here except for final temp comparisons and assay. Okay for the M. E. to take him?”

Gross opened his mouth, sighed and shut it again. He turned to B’russ’r. “Would that be all right with you, now?” he said.

B’russ’r bowed politely. “Thank you for asking,” he said, just as if Gross had had any choice; once a Beri was there as consult, even self-called as B’russ’r clearly had been, he had official standing. Berigot noticed things—and had no prejudices. “Knave is of official standing as well. If all right for him, it is all right for me.”

Gross turned a little redder. “Wonderful, then,” he said. “Just wonderful. Knave, how is it for you? I mean to say, now: may we go ahead and do our work?”

“Go right ahead,” I said. “You have my cheerful permission.”