Читать книгу The Counterfeit Heinlein - Laurence M. Janifer - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

There was once something called science-fiction. (I know, I know, there is now, but it’s not the same—this was preSpace.) It began more than a hundred years before the Clean Slate War, and for a while it concentrated on what it kept calling exciting stories of science—look at all the wonders today’s mad scientists are going to bring us any decade now, that sort of thing. There was a Julius Verne, for instance—some of his things have survived, but not 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, which irritates me; I’ve always wondered how many of those Leagues were red-headed, like the one in Sherlock Holmes. And there was The Foot of the Gods by Herbert Wells, which also hasn’t survived (although War of the Worlds did, and is actually fairly exciting, if you can get hold of a copy somewhere).

But science-fiction started to change; things do. It began to concentrate more on people and on ideas (it was a commonplace of the time to say that science-fiction was a literature of ideas, though I am damned if I can imagine anything else for a literature to be of), while the detailed science surrendered the steering wheel and slowly slid into the back seat.

Just a little while after that, science-fiction began to deal in matters that were scientific only by the most haphazard of definitions—everything from parapsychology (not just telepathy; telepathy exists, but this was something else again), a charming superstition a few especially wishful ancients thought of as psychology, and eventually such things as witchcraft, numerology and the Great Beyond.

And then ... well, you get the idea. After the Clean Slate War, when enough pieces had been picked up and shoved back together, there began to be science-fiction again, but it had very little to do with science—any more than a great many comic-books or comic-tapes have to do with comedy.

Now, there are people who know all this in great detail, or in as great detail as the surviving, and often confusing, records allow. (Was there really an author named Spider Callahan? Alfred Blishter?) I know it in fits and starts, because I did have a scrappy sort of Classical education once upon a time, and some of it has stuck. More, I took the quick course, so to speak, when Ping first mentioned his job to me; I collected all the information I could get at, and three or four sorts I hadn’t really thought I could get at until I tried.

That, after all, is what a Survivor does—that’s what it says on my business cards: Gerald Knave, Survivor—in spite of what you’re used to seeing on your 3V. Up there, a Survivor is a grim, wordless sort of hero with a hot beamer in each hand and a great willingness to kill off half the cast on no very special provocation.

A Survivor, and I’m sorry to shatter such illusions as you may be harboring, is essentially an information collector. You never know, in my trade, just which bit of information you are going to need in the Hell of a hurry, but you do know that, when the red signal lights up, you are not going to have the time to find it. Therefore, you gather in everything available, as long beforehand as you can manage, and you keep gathering in more information, more or less all the time.

This particular job—Ping’s job, for which I read up on my preSpace sf, as it was called—actually began rather suddenly, and pre-Ping, with someone taking a shot at me.

There I was, sitting quietly in a leased apartment on Ravenal—where I had gone to hobnob with some of the friends I have in high places—drinking coffee out of a china cup, watching my rented Totum direct two rented Robbies in the fine points of apartment-cleaning, and trying to decide which of several interesting restaurants I was going to invite Jamie Arthur to, later that evening. The coffee was Sumatra Mandheling, which Ravenal imports for a few discerning Nobels and suchlike. The time was fifteen-eleven, City Two local time; Ravenal has a twenty-four hour day, almost exactly, and even a twelve-month year. I take my coffee with cream and sugar, not in excessive amounts.

Well, how did I know which fact might be the important one? It was a coolish late-Spring day, and I had my window open, and just at fifteen-eleven (which I am always going to think of as three-eleven P. M., since I do not have the Scientific Mind) something went whizz-crash-tinkle, and my lap was full of hot coffee. I was holding the cup’s handle; the rest of the china had left it, to complicate the apartment-cleaning situation.

I sprang up with many an eager curse, dropping the handle and dabbing at my pants with both hands. In something under a full second, sanity returned, and I dropped to the floor, where I lay with my face in the luxurious carpet for ten full minutes. The Totum directed the Robbies to clean around me, not over me; Ravenal’s rental machines, as one would expect, are fairly bright.

Any sensible marksman, I kept telling myself angrily, having missed the first shot by a reasonably thick hair, would have potted me in that endless second before I dropped. I kept muttering that into the damn carpet while I waited. For ten solid minutes. Of course it’s not especially helpful to set time limits on a marksman’s patience when you have no idea who the Hell he is, but ten minutes seemed about right as a wild guess, even adding in a safety factor.

So I struggled upward, let my machines get on with their work, and didn’t get shot at again.

And nothing else of vital importance happened that day or that night. Jamie and I had a pleasant dinner and a pleasant few hours of chat (I’d finally chosen an “old-fashioned British pub” with surprisingly good food, if all too predictable atmosphere—the name had at the least a definitely ancient feel: the Rose & Corona).

I did not, just by the way, spend my time waiting nervously to get shot at again. My hopeful assassin had had his one shot, and he hadn’t taken any more. It seemed unlikely that he’d be bucketing around all over City Two (that’s Ravenal for you: extraordinarily bright and accomplished people, with no literary imagination whatever—not even Twin City or Doubleville) angling for another try.

No, I relaxed and enjoyed myself, and Jamie seemed to enjoy himself, and I went to bed in a calm and fairly peaceful mood.

I did make quite certain to shut and lock all the nice, unbreakable-glassex windows.

And the next day at ten-thirty—somebody had asked round about me, and discovered that I keep civilized hours—the telephone rang, and it was Ping, whom I’d never so much as heard of before, offering me a job.

* * * *

His name was Ping Boom, and I am not making that up—my God, who would? It is amazing, if not downright sickening, what some parents will do to saddle their offspring with lifelong jeers and scars. Admittedly Boom is a surname that does cry out for ridicule, but would Abraham Boom, or Callian Boom, get quite the reaction I gave Ping Boom when he told me who he was? I doubt it.

But when I was persuaded that he wasn’t trying to spoof me somehow, he turned out to be a very businesslike fellow. I agreed to meet him after I’d treated myself to a lovely, hand-crafted small breakfast, and, nicely cleaned up, was in his office by noon, or noon-thirty. “We want you to do a very specific job for us, Knave,” he said. He was a short, thin fellow with sparse whitish hair, large, ancient-looking eyeglasses, and a mouth that was better than halfway toward Pursed Disapproval.

I told him to specify away.

“We want you to find a missing manuscript. It’s quite valueless, but enormously important.”

I asked him, as calmly as possible, just how that combination worked out; at first glance, it seemed just a trifle odd.

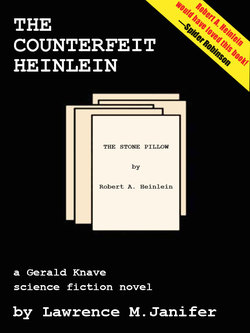

“It’s a forgery,” he said. “A counterfeit. It purports to be the work of a preSpace writer named Robert Heinlein.”

I’d known more than the average reader about Heinlein even then—my Classical schooling—and he wasn’t quite preSpace; when the first moon landing was made (by Armstrong and Harriman, I believe) Heinlein had still been alive.

“If it’s a forgery,” I said in a reasonable tone, “then why is it valuable?”

“We can’t yet determine just how the forgery was managed,” he said. “It’s so nearly a perfect counterfeit that it fooled our experts for over four years—and our experts, Knave, know their business. Or businesses, of course.”

We were, after all, on Ravenal, home of the Ravenal Scholarte (where Ping Boom was co-chief librarian, Manuscript Division). I agreed that Ravenal’s experts knew their businesses; they always do.

“So you want me to track down the manuscript,” I said.

“Exactly,” Ping Boom said. “It’s been stolen—very neatly, too. There’s been some talent at work here.”

We discussed some other matters—payment, for instance. I won’t bother you with the whining and screaming on both sides, so common in such discussions, but we finally managed to arrive at a mutually unsatisfactory figure, and I agreed to come down and take a look at the scene of the crime, as the first step in finding the missing non-Heinlein.

“There’s nothing to see, Knave,” Ping Boom told me.

“That’s exactly what I want to look at,” I said, and we settled on a time.