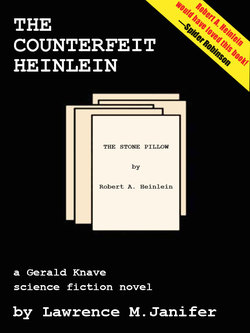

Читать книгу The Counterfeit Heinlein - Laurence M. Janifer - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

Everything in the universe looks like something we already know, even when it acts very differently—which may be a statement about the universe, and may be a statement about the way we know things. Walking-trees look like trees, though they’re not, and the Berigot—

Well, when you tell someone they’re a race of sailplaners, for some reason the immediate reaction is Bats, and you start hearing a lot about Dracula and other ancients. The Berigot don’t act like bats (except that they do flock—but even people flock), and they don’t look like bats—they look like giant flying squirrels. They’re large, and they’re furry rather than, say, hairy, and their arms do look fairly small and fragile for the size of a Beri. Their heads even seem to be pouched, although the shape isn’t due to a pouch system but to twin air-bladders; that’s how they speak. The whole breathing system is reserved for breathing.

The wingspan is very large, of course, though even so they can’t really fly. They walk at times, with a whole range of mincing gaits that look as though they ought to be very painful, and they swoop and dip at times—they prefer swooping and dipping, and so would I, but that sort of thing needs height and clear space, which are not always available. At home, they live in what some people call nests and other people call perches, and use the ground for large storage buildings; at work they enter and leave from perches set high enough from the ground to allow of some sailplaning.

They come from a planet called Denderus (their name for it; humanity has politely agreed to stick with it, since humanity can pronounce it), which has a Standard gravity of .89, and air as thick as, say, Earth’s—this is possible because the stuff isn’t air, it’s a denser set of compounds. The Berigot can’t breathe our air, and sensibly don’t try; even if you have seen a Beri or two, you’ve never seen one without his transparent head-bubble. The exchange technique isn’t quite beyond human skill, but it is said that only four men on Ravenal, and perhaps two more elsewhere, understand how the bubbles transform Ravenal’s air into stuff a Beri can breathe.

There’s a small human presence on Denderus, and an equally small Berigot presence in the Comity Worlds, almost all either on Earth where the diplomats live or on Ravenal, where the Berigot have found appropriate work. They are probably the best librarians in the galaxy (Kelans might dispute this, but the Kelans aren’t much on really big libraries, preferring to carry their massive knowledge around inside their rather small heads).

People do tend to think of a librarian as someone who will direct you to the spools for Non-human Dance Troupes, and who spends a staggering proportion of his time saying Shhh. This is not quite the whole picture; librarians are a vitally important part of any search for knowledge, though virtually nobody knows this except other librarians, and a scattering of searchers.

I know it because I have had to search for some odd things now and again, in the course of an active life. Ravenal knows it because the Ravenal Scholarte and all its associated cities are always searching, though they seldom have any clear idea of what they’re searching for; if they knew, they’d already have it.

And Berigot know it because collecting facts is what Berigot do.

I’ve said a little while ago that a Survivor—me, for instance—is first of all an information collector, and as an information collector, I’m fairly good—for a human being. For a Beri, I would be classified as Deeply, even Laughably Defective. The Beri collect information the way human beings invent weapons—with constancy, facility and blinding speed. They would make me feel horribly inferior—if they did anything else.

Oh, they eat and sleep and mate (four sexes, two He and two She, all needed not only for reproduction but for a normal social life), but their reproductive (and social) life is passionless and managed pretty well by rote, they have no hobbies except those associated with information-collecting, and they have only very recently begun to wonder whether there is anything in the world at all except information-collecting. Human beings are the bit of information that has started them wondering, and Ravenal has contributed most heavily, since Ravenal is the sample of humanity a Beri is most likely to see.

Someone on Ravenal, about seventy years ago, awoke to the fact that a race of information-collectors would make marvelous librarians, and began talks with the Berigot. And the Berigot have been working on Ravenal ever since.

Well, what does a librarian do, except point you at the spools you need, or tell you to shhh?

He—and if the pronoun has been irritating you, I’m afraid you’ll just have to be irritated; it’s all I can do, and I’m robbing the Berigot of two pronouns as it is—he puts one piece of information together with another piece of information.

I’ve heard of that process as the one absolute definition of intelligence. I agree: the ability to take two facts and make a third fact is intelligence, and everything else is something else. Unfortunately, it would take either the Kelans or an even brighter race to come up with a useful test for it.

But the Berigot are very good at it. It’s what librarians do: they look into Non-Human Dance Troupes for a bit, and remember something they noticed the last time they looked into Molar Physics a bit, and they see that the two things have some common features.

Then they tell people about this—either personally or, much more frequently, by filing a cross-index note. Molar physicists can now get a bit of help from non-human dance troupes, and vice versa.

This goes on all the time, in fields even more widely separated than my examples. Librarians are the great cross-pollinators of the universe, and they make things grow—things like ideas, and inventions, and discoveries, and civilizations.

Ravenal, naturally, has the best librarians known. And I was off to see one.

I’d met a few Berigot, on a previous stopover, but for me the meetings had just been a few minutes of casual chatter. For a Beri nothing is casual (which means that nothing is important, either; if you don’t have a scale, you don’t have a top to it), and I felt sure somebody would remember me—though possibly not at Berigot Services, which is staffed by human beings.

Services greeted me as a total stranger, and called Ping to check on me. They’re a deeply suspicious bunch, and they should be; five years ago, Ravenal (just about five and a third, Standard), according to report, some nut decided to get dangerous, and tried shooting at Berigot. He made a nice, if somewhat ragged, hole in each of three Berigot—in each case puncturing some part of the strong webbing with which a Beri sailplanes; only natural, as it’s the biggest target in flight, and all three were hit while off the ground.

Police built up a fair picture of the nut, who had been using an unfashionable, but very damaging, slug gun, and their final working theory was, believe it or not, that he’d been a sports maniac, and had decided the Berigot were fair game, like ducks or some such. They’d never managed to snare him, despite some helpful data (by Berigot, of course, who notice things), and since that little series of incidents Berigot Services has been just a hair paranoid.

The Berigot themselves take things more calmly; their feeling seems to be that nuts happen, the way earthquakes and economic depressions happen, and one has to get on with life.

So when I knocked on the door of the Frontier Worlds History room, B’russ’r B’dige simply unlocked the field and poked his head out to see who’d come along.

“Gerald Knave,” I said.

“My goodness,” he said. His voice was clear, with a slight echo, and a little high even for Berigot, who tend to the tenor ranges. “I know of you, Knave. Have you come to add to my knowledge? Come in, please come right in.”

“I’ve come to borrow from it,” I said. “I’m here about the Heinlein manuscript.”

B’russ’r smiled. Berigot have rather pinched, open smiles, and they look more pleasant than my description does. “Ah, Heinlein,” he said. “‘What are the facts? Again and again and again—what are the facts? You pilot always into an unknown future; facts are your single clue.’ Our attitude exactly, Knave.”

He stepped aside and I went in, and he closed the field firmly behind me.

“Now, then,” he said. “A phrase, by the way, whose oddity has always appealed to me—now, then—well, what do you want to know?”

I found a chair and sat down. B’russ’r remained standing, of course, his legs locked; a Beri can’t sit and doesn’t want to. I took out a cigarette (Inoson Smoking Pleasure Tubes, Guaranteed Harmless—no Earth tobaccos—but most people do seem to call them cigarettes) and offered him one. He nodded and took one and stuck it through his head-bubble (I’d had no idea it passed Inoson Smoking Pleasure Tubes as well as sight and sound) into his mouth. “I have never understood why humans burn these things,” he said, and began to chew, slowly. “I don’t think I have ever seen cigarettes dyed red before, Knave.”

I explained that I had them made, lit mine while B’russ’r found a handsome ashtray—map of the Ravenal Scholarte pressed between glassex panels, in gold—and explained matters to him. He grew very grave, munching away at his cigarette.

“Someone should have been on duty,” he said. “Someone should have taken notice.”

“Notice of what?” I said. B’russ’r shook his head.

“Of the actual theft,” he said. “The process itself—it must have taken appreciable time, after all.”

“Now that’s what I want to know,” I said. “How was it managed? What do you know?”

“Know? Very little,” he said. He was still chewing thoughtfully. Apparently Berigot don’t spit. “We have some deductions, and the police have told us of a very few—ah—clues.”

I asked for a consecutive story first, and then got down to details and went back and forth. I made notes as we went along, and B’russ’r watched me do that with a curious resignation. When I asked him why, he said: “We use a better method: upload data directly to the nervous system, as non-sensory input, for classification and filing. Automatic, but humans somehow won’t take to it.”

“I wonder why not?” I said, not even wanting to think about shoving megabytes of strange data into my nervous system.

“I think it must be the loading system,” he said. “It is bulky, but we found room by shrinking parts of our reproductive systems. I’m sure humans could do that.”

“Well,” I said, smiling with some effort, “maybe they will. Some day.” A dedicated race, the Berigot.