Читать книгу The Counterfeit Heinlein - Laurence M. Janifer - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FIVE

They were also less informative. They did open a bag or two out of their hoard on the case, but none of the bags contained anything I could think of any way to use. They had a few flakes of dried skin from a bit of floor near the case—people shed, and few beings outside police labs know it—but they’d been too small and too trampled to provide anything much in the way of data. They had the beginnings of a typing on the dried skin, just enough to limit the suspects to fifty-five million. With great good luck and much work, perhaps fifty-three million.

After a while I left, feeling just a bit lost, and thoroughly inferior until I remembered that B’russ’r, certainly, had also had a chance at the police files, and had got no more help from them than I had.

I was heading back to my rooms, to call the Master and get him to call Robbin—unless one is one of three people in the universe, one does not call Robbin. I was on a main boulevard, nicely tree-lined (maple again) and uncrowded. The time was eighteen-seventeen, or sensibly 6:17 P. M. I was not smoking, muttering or whistling, and I was wearing nothing unusual. I did need a haircut, and had for a few days.

The slug hit the sidewalk less than a foot behind me. This time there was no hesitation; I leapt as if cued for the building line and dropped flat there, bruising my nose, one shoulder and both knees. I didn’t know about the bruises until some time later; I was much too busy listening and, as far as my position allowed, looking—though I neither saw nor heard anything helpful.

A few passers-by stopped to help me. I lay still until I had collected a small crowd of hesitant Samaritans (“Don’t move him, you don’t know what’s wrong”), and then allowed them to raise me up, dust me off and help me to a nearby shop. I stayed in the middle of the crowd until well inside the shop, which sold portable walls.

A nice portable wall sounded like a fine idea, but I didn’t really have time, and even if pressed couldn’t carry one everywhere; people would talk. Four or five Samaritans had given the shop-keeper the story of my rescue, very variously, and I sank down on a small chair over by one (permanent) wall and breathed for a little while.

Ten minutes, in fact. It might have been eleven. In either case, I’d given my assassin more room than I had before, because all that Samaritan-collecting had taken time.

Then I stood up, and thanked the wallman, and walked out into the early-evening light. It took me another ten minutes to amble on home, during which time nothing of any interest happened to me.

And, once home, I made completely sure every unbreakable glassex window was shut and locked, told the Totum to take itself and both Robbies to somewhere restful until called for, dressed my small wounds a little, and got to the phone. Voice only, image available for some extra button-pushing and a nice steep charge, but I was not looking my best, and forwent it.

I hadn’t spoken to Master Higsbee in five years, and it was a delight, in a way, to hear that rasp of his again—a sound like an unoiled camshaft with attitude. The phone rang twice (on Ravenal, by the way, it doesn’t ring—for some reason, it blips) and a voice said: “Who?”

It is no damn way to answer the phone, and never will be. “Knave,” I said. “Hello, Master. How are you?”

“Ah, Gerald,” he said. No one else in the entire Galactic collection of vocal races calls me Gerald. I think I dislike it. “A long time. And how should I be? An old blind man, helpless and alone, in a world made for the sighted and the fleet—Gerald, how should I be?”

I sighed a little. The Master would always be the Master, after all. “You’ll be fine,” I said. “You always are.”

A snort from the unoiled camshaft. “By dint of unceasing effort, Gerald, I remain alive and—so far as I may—functioning. In sixty-one months Standard, what have you done?”

I took his word for the time; one could. And I knew what he meant. “Not much, Master,” I said. “I did learn how to lockpick a hologram safe, and I’ve had a few liaisons.”

“Children may result from the liaisons, one cannot be wholly sure,” he said. “Good. The lockpick is too simple for you, Gerald—you must stretch yourself.”

I refrained from saying that I’d stretched myself quite a lot in some of the liaisons. When talking to Master Higsbee, one lets the Master make the jokes.

“I’ll look round for other things,” I said.

He sighed. A cross between a wheeze and a derby-muted trumpet. “Well, enough,” he said. “What have you called to demand of an old man?”

“I’ve got a problem,” I said, and Master Higsbee said at once:

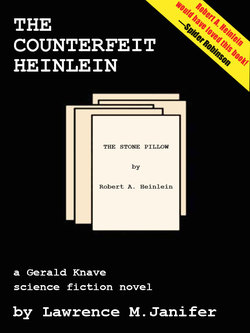

“The Heinlein forgery, of course. What do you need of me?”

There are days when I am not at speed with the entire rest of the universe. This never feels comfortable. “You’ve heard about the theft,” I said.

“I have,” the unoiled camshaft told me. “Gerald, put out the cigarette. The smoke does not of course come through this connection, but the signal of it, your changes in breathing, discomfits me.”

I stubbed out the Inoson Smoking Pleasure T. Why could I not need someone else?

Because, damn it, there wasn’t anyone else. Not like the Master. “I need a full consult,” I said. “Examination of scene, questioning of some people. Everything. And a running consult with me on all aspects—all but one.”

“You will handle one aspect alone, Gerald?” he said. “If so, which one?”

“Not alone,” I said, and he said:

“I will call her in—sixty-three minutes. The soonest possible. She will then call you.”

“Direct? Herself?” I said. “Robbin has changed.”

“Improved, they think,” he said. “To some degree.”

I nodded at the phone. I was not wholly sure the Master couldn’t detect that in some way. Changes in pressure, perhaps. The sound of my head moving in the air. After a second I said: “I’ll be waiting. We’ll arrange a meeting after you’ve both been around the block on this. I’ll give Robbin names and places—writing them down will give her something to do, and she can tell you, giving her something more.”

“You are learning, Gerald,” he said. Distant approval. I seldom got anything that warm and cozy from the Master. “When we spoke last, you would not have thought of that.”

“Thanks,” I said. I wanted to ask him once again if he were still sure he would not have his eyes restored, and decided against it. It would be badgering, a very bad thing.

“I will call you when we have—been around the block, Gerald, and we will all meet. It has been good to hear from you. Finished.”

The connection broke. I sighed yet again and put the phone away, and made myself a cheese sandwich (eight minutes) and a pot of coffee (twenty-two minutes, and worth it). I ate, drank, washed the dishes, and did a little light dusting while I waited for the phone to ring. There are times when I am just too busied, too frantic or too damned lazy, but, most days and weeks, I do my own housekeeping. It’s a bit like a hobby—restful, and a way to free the mind while the body occupies itself. Home or away, any Totum and Robbies I have around are just a tad underworked, I think. They don’t complain of it.

Forty-eight minutes later, dustrag stored away and an edge of boredom starting to set in, the phone rang. I got it on the first blip, and there she was, or her voice anyhow, after sixty-one months Standard, the Master’s figures, the usual breathless childish soprano bleat.

“Hello there, thank you so much for thinking of me, Sir, do you want me to help with your work? Master Higsbee says you do.”

I was always rethinking it, but I felt just then that I liked Sir a few hairs less than Gerald. “I do want your help, Robbin,” I said. “Do you know the situation, love?”

Robbin was thirty-two Standard years old. At times she very nearly looked as old as twenty. At times she very nearly acted as old as eighteen, but not often. “Of course I do, Master Higsbee told me about it,” she said. “We were on the phone for a long time.” She giggled. I don’t get to hear giggles very much, and prefer my life so arranged. “Sometimes I think he likes me,” Robbin Tress said in her teeny breathless voice.

“Well, good, I’m sure he does,” I said. The girl could reduce me to babbling banality in any twenty-second space of time. “Then you know you’re to take down names and places?”

“My pen is right here, Sir, all ready.” I gave her a list, from B’russ’r B’dige through Ping Boom (she giggled) to a few police officers male and female. The Master, I knew without thinking about it, was going to have to interview the females, and try to get Robbin what she needed from them.

And the few important places as far as I knew them: the room where the manuscript had been, the lawn outside, the Berigot perches for that building. There would of course be more. I had the sudden lost feeling you get when you’ve forgotten something important, and added just in time my apartment and the stretch of street near the portable-wall shop. “Do you want me to see your apartment while you’re in it?” the breathless little voice asked.

I stared at the phone. “Do you do that now?” I said.

“Sometimes,” Robbin said. “For people I know a long time. The Master would have to come too, though, if you don’t mind, Sir.”

I nodded, and then said: “Fine. When?”

“An hour and a half, Sir?” she said. “I will call him, and then wait for him here.”

Robbin had improved out of all belief. “An hour and a half,” I said, and began to give her directions.

“Oh, Sir, don’t bother about that, please don’t trouble yourself,” the breathless voice said. “The Master will know, he’ll take me. Closed car, Sir, I really have done it before.”

“Fine,” I said. “I’ll see you both then.”

“Goodbye, Sir,” Robbin said, “and thank you so much again for thinking of me.”

Finished. It might be that the Master’s way of ending a phone talk had a point. I said goodbye politely, put the phone away and thought about refreshments. Coffee of course. And—

I had time for one fairly speedy shopping trip. Nobody shot at me.