Читать книгу No Stopping Train - Les Plesko - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

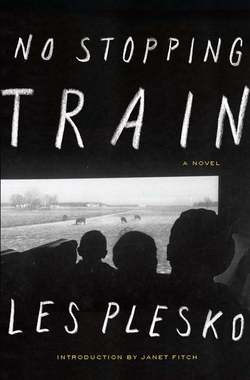

ОглавлениеIt’s been four days since you’ve touched my arms or my neck or my forehead or cheeks or my waist or the small of my back. A week since we lost the revolt and the borders came down, I could climb on this train, I could run while I left you behind. I can’t sleep for bad dreams. I hardly dare look at myself in the blackness the train glass reflects, though it smoothes my classic moonface, soothes my eyes that in daytime just ache.

You used to call me beautiful. My almond-shaped eyes, the cupidity of my mouth was a puffy kiss-bitten surprise. I was vain of my thighs and my belly and legs, the pleasing contour of my ass and my hips.

After the war, the big one, I thought my flesh was like Hungary’s meadows and hills, even with shrapnel and metal and broken plough teeth underneath. Now I don’t trust metaphor, I hardly believe what I see when I look at myself. My mouth tastes like my mother’s unwash, her starved breath.

I lay beside her in our bed, jolted awake fully dressed, dawn swarmy as newspaper print.

“Stay with me, don’t go out,” Alma said.

“I’ll go anyway, then you’ll be sorry you asked,” I replied.

I hadn’t slept with you yet. What I owned was my own, I carried my needles and spools and the war in my head.

“Everyone’s come home again and you’re going away,” Alma said. She turned on her side, a weak smear of light on her tattered nightgown.

“Make me feel bad, it’s what you do best,” I replied, chewed the sleeves of my dead father’s coat, its tail trailing crumbs by the bed.

“I recall pushing you in the pram,” Alma said.

“Pull out all the stops,” I replied.

“We paused on a bench by the lily pad pond, fed the ducks,” Alma said.

“It rained, you hate ducks, you never bothered to cover my head.”

“I threw myself over you when bombs fell.”

“It was me who did that for you,” I replied.

Alma rubbed her hand where her swapped wedding band left its naked indent. “I never wanted a child.”

I didn’t bother to sigh. “Tell me again how you stopped eating on purpose back then.”

“I lay on my belly, my fists to my gut, wished you dead,” Alma said.

My fingers drew tight figure eights on the sheetless mattress. “In school we played a game, ‘put your mother on the ceiling,’” I said. “We had to imagine our mothers up there. One of us said his mother baked pies, another’s saved porcelain figurines.”

“Smart move during a war,” Alma said.

I had a habit of narrowing my eyes against sarcasm then. “I said you collected bad thoughts.”

Alma tapped her nails on her teeth. “When I was pregnant, I tried to slip on the ice, but your father kept grabbing my arm. I told him, instead of delivering a baby, I’ll give birth to a bone through my leg.” My mother hurt to look at. The light through her gown illuminated her belly and breasts. “Once I was sure about you, I went to the park, I clung to the Tilt-A-Whirl’s bars, let it drag me around.” Alma smiled.

“So you’ve told me,” I said, but it choked me all over again.

“They had to tie me to the hospital bed so I wouldn’t jump out the window,” she said.

I smiled back nonetheless. “If you’d eaten better, maybe you’d have had the strength.”

We both laughed. I could afford to, I thought. Because, Sandor, you waited for me in the street with fish or with soap or a silver barrette. I believed you would always be there. My belief made me think I could be cavalier yet remain generous. I touched my mother, though I was never supposed to do that, all brittle bones through her gown and her hair tangled up. She wrenched free of my hands, hugged her chest. “That’s a cheap shot. Don’t leave me with something I’ll miss,” Alma said. But I did.