Читать книгу No Stopping Train - Les Plesko - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

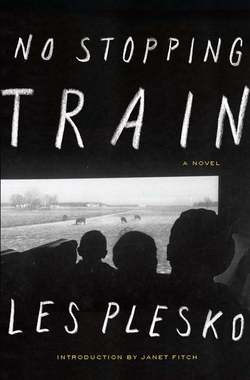

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Has there ever been a writer so committed to the page and what went on it as Les Plesko? He believed in Art, in all its honesty and beauty. The only thing he loathed was that which affronted the Real—anything false, slick, self-serving. He was in rebellion from all that. In a time which applauds those values, he was purposefully anti-trend. You saw it in his unregenerate smoking, the mismatched socks, the wild head of straggly hair, his carlessness in vast, far-flung Los Angeles. From time to time, his students said, people dropped money into his coffee cup outside a favorite Venice Beach coffee house, thinking him homeless. It was all part of his High Beat Aesthetic, which was both a conscious embrace of his romantic ideal and an increasingly involuntary corner he’d lived himself into.

I met him in the early 1990s, in the days of the legendary Kate Braverman’s writing workshop held every other Saturday in her apartment on Palm Drive. There I saw him finish his first novel, The Last Bongo Sunset, and start the book that would become No Stopping Train. Even in those early days, his views on fiction became our mantras. “Don’t have ideas,” he’d say, which always made me laugh. What could that possibly mean? How could you write and not have ideas? It was only as I struggled with my own writing that the meaning—and the wisdom—became clear. It meant: don’t force the work into a shape. It meant: don’t lead with your head. Don’t know so much. Leave room to discover something.

Writing for Les was an activity of soul, of memory, of sound and dreaming, not an intellectual exercise, not a game. He shared so much with those around him—time, friendship, passion, a subtle intelligence, a wacky humor, but most of all, the flame of his purposefulness that this was the noble endeavor. His presence was a reminder to treasure the deep and the true.

But now he’s gone. Dead, by suicide, on a September morning in Venice Beach, at the age of fifty-nine. He had become a cult figure in Los Angeles literary circles, a writer’s writer, as Mayakovsky called Khlebnikov, “Not a poet for the consumer. A poet for the producer.” A brilliant teacher, he taught over 1,000 creative writing students across a twenty-year career at UCLA extension. Yet at the time of his death, he was virtually unknown outside California.

Many of his friends from the old Braverman group wondered what would be done with his papers, especially the famously unpublished Hungarian novel No Stopping Train. It had been born in wisps and curls of smoke, and grew denser and more layered over a period of six years—though never less mysterious. It was the finest example of the unique process of addition and especially erasure, which was the essence of Plesko at work.

The tragedy of Les, as well as his greatest virtue, lay in his absolutely uncompromising stance on art and life. Unfashionably, he recoiled from any hint of commercialism. He fought against any sort of pandering to the reader, “smoothing out the bumps,” planting “helpful” directional arrows, catering to the American preference for the shout over the whisper. He instinctively moved to the edges, deserts, marginal people. Suggestion, nuance, abraded surfaces were his métier, and he had confidence in readers who could walk through the doors he had opened. He required a certain sort of skilled reader who could bring his or her own sensitivities to the task, a reader able to enter his elusive work and let it unfold on its own terms.

One cannot read quickly through a Les Plesko book—don’t even try. It’s not meant for speed-reading. A reader who wants to “cut to the chase” will find it vaporizing in his hands. But be patient, reader, and this book will unlock itself for you.

Les wrote for those of us who can hear a confession, who know how to hear behind halting words to the depths of a soul revealing itself. Reading Les Plesko is like listening to a broadcast late at night, an urgent communication textured by distance and static. It’s a lover’s reception of an intimate call in the middle of the night. You hold your breath for the cadence, wait for the meaning to unfold.

His imagination has a certain texture—like overexposed film, a Polaroid taken at noontime in a desert in the 1970s. Light and sanded glass and desperate romance, these are Les’s signatures. As a man, Les was the ultimate romantic, always in love with someone, and there seemed to be no shortage of women ready to be entranced by his rumpled, Beat self.

Love was his subject, forever complicated, not so much by the conventional external obstacles—family, money, even the dire obstacles of history—as by the contradictory personalities of the lovers themselves and the messy interlocking relationships created by desire and fate. He was alert to the strange eddies of romantic entanglement, the way lovers test one another, the way they create a private world in which desire and rebellion and privacy form the rooms they live in, and language both magnetizes and repels at the very same time.

• • •

Then there’s that sound. How do I describe the sound of a Les Plesko sentence? It’s a very particular cadence, a certain number of beats—I hear it in my own writing sometimes, that subtle music, a certain choice of vocabulary and a characteristic stress pattern. I hear it in the writing of others who knew him, people who worked with him, who read him. That unmistakable, addictive, lyrical Les Plesko line—it always makes me smile. He had it back in those early workshop days, and he had it to the end. Read a paragraph out loud, you’ll hear it:

Now I can’t forget the good parts, even under this afternoon light that absolves what remains. The name of this place moving past which means small bloody earth. The man with one arm by the blinking switchbox feeds small nervous birds, and I think how before the war, he might have tried cupping their tight beating hearts in both fists.

To say he was a careful writer only begins to address his precision. Les Plesko worked like a man crawling under barbed wire, moving from word to word, feeling his way, refusing to continue until each sentence offered up its full potential of fragrance and emotion. And then in a few days or weeks, more than likely he might throw it all out. For him “less is more” wasn’t just a saying, it was religion.

• • •

Once No Stopping Train was finished, Plesko began the search for a major publisher willing to accept it. Every year for fifteen years, he sent it out. But the consolidation of publishing houses worked against him. Consolidation meant that novels were far more likely than ever to be judged for “reader friendliness” and potential for commercial success than for invention and strangeness and beauty. A work like No Stopping Train had an ever-decreasing chance in such a market—and Les would have recoiled even from the use of such terms as “market” or “marketplace” when referencing literature. The repulsive necessity of reducing creative works to a unit of commerce. It was one of the great sorrows of his life that this, his best book, could not manage to hack its way through the thicket of obstacles growing ever more dense on the road to a wider reading public.

Yet at the same time, he refused to consider casual publication for this novel. His subsequent books, his desert novel Slow Lie Detector and the tender love story Who I Was, were both published by his friend Michael Deyermond in loving editions in Venice Beach (Equator Books and MDMH Books, repectively). But Les was adamant; he wanted No Stopping Train to reach beyond the small, appreciative literary circles of Southern California. He knew that a broader readership existed for this book, but it would require a more experienced literary house to connect to them.

A man is not a book, and Les Plesko was more than his work, though he shared many attributes with his fiction. Like his fiction, he was quixotic, a romantic, a gentle cynic, an intellectual and also an anti-intellectual, and a Chaplinesque little tramp cycling along on a wobbly bicycle. He was nonjudgmental, in a wry, European, pessimistic way. He didn’t even curse. “Oh, brother,” was the worst it got—usually said in response to some display of sentimentality or self-importance.

He was Hungarian, he lived steps from the sand in Venice Beach, he didn’t have two socks that matched. He lived in a single room. Students who loved him offered swankier sublets and he’d go, but found he couldn’t sleep in these more elegant digs. “Too much,” he’d say. He never left his Venice Beach room very long. Once, after he’d lost it during a sublet, he rented the room next door until his own was free again. He drew a map of it for his young nephews, as if it were a kingdom. I think it was the very simplicity of his circumstances which allowed him to live completely in the life of his romantic, Beat imagination.

But he was far from impoverished. Though living in one room, the breadth and depth of all Western civilization was his. A short glance at his list of recommended books, preserved by his most devoted students, reveals just how rich that life had been. The list is viewable on their tribute website www.pleskoism.wordpress.com.

• • •

Hungary, 1956. A Soviet invasion to stifle a growing movement for independence, this moment can be viewed in many ways as the precursor to The Unbearable Lightness of Being’s Czechoslovakia. The collision had its roots in the Second World War, where Hungary fought on the side of the Axis and experienced great hardship in defeat. In the division of Europe, Hungary fell on the Soviet side, so scores were being settled as people tried to survive, a situation Plesko brilliantly illuminates in his novel. No Stopping Train starts with the war and its aftermath, the girl Margit and her embittered mother, her love affair and eventual marriage to the document forger Sandor, and their involvement with the fearsome, magnetic redheaded Erzhebet, whom he’d once saved from the camps. In the years leading to the Hungarian Revolution, love and alliances will shift repeatedly, as each character struggles with his or her own level of hope and despair.

Plesko specifically chose his homeland as the setting for his magnum opus. Born in 1954 Budapest, Laszlo Sandor was the child of a love affair between a pretty young blonde, Zsuzsa, and a man whose identity Les would not know until he returned to Hungary years later, when he discovered his father had been a famous actor. Said longtime colleague, the writer Julianne Cohen, “He brought home a head shot. The resemblance, uncanny. And a story of how the actor had leapt from a building to his death.” A terrible prefiguration of Les’s suicide in the fall of 2013.

In 1956, his mother fled across the border with a new husband, Gyorgy Pleszko, making her way to America and leaving two-year-old Laszlo behind with her elderly parents who struggled with the realities of the revolution. She sent for him at the age of seven. He arrived in Boston, speaking only Hungarian, to meet his mother, a glamorous near-stranger, and his new family, which now included a baby half-brother. A new name. And a new language.

His encounter with English began a love affair that continued for the rest of his life. “Immediately, he was in school, and nobody spoke Hungarian, so he listened in from the back until sounds took shape and made a kind of music,” said Cohen. “He listened to the radio, watched TV and listened to his mother and stepfather, who never spoke Hungarian, fiddled with a reel-to-reel tape recorder until the music became word. At some point he lost his fluency in Hungarian, gave it up for new and interesting things, all that America had to offer a boy in the ’60s. Les was in love with language and in love with love and fell in love with the music all around him.”

But the ’60s in America had their pitfalls: “He made friends with people who were going places. San Francisco, Santa Cruz,” she recalled. “He tried college but he fell in love with heroin and dropped out. When you read The Last Bongo Sunset you’ll come to know how he broke his own heart. But the tenacious [side of himself] quit using and thought maybe he could be an artist, a musician. He recognized he possessed a feel for word and deed and an eye for beauty. So he hit the road, taking jobs along the way, searching. Fell in love with an older married woman as a hand on her ranch in the desert. It ended badly, broken hearts and incipient violence. Made his way back to Los Angeles: flag man for crop dusters, country-western DJ. He took a sales job. He had a compelling voice; it roped you in and kept you there. Laced with smoke, sorrow, and an unbeliever’s faith in resurrection, he told the truth and you could trust that.”

I’ve seen those pictures of Les as a young man, a businessman with a phone to his ear, in ’70s wide lapels. They astonished me, for I knew him only after these formational years, the years that gave the raw edge to his first novel, in new sobriety in the Braverman workshop, writing the book in which he found his unique voice, his tone as an artist, and a moment of accolades. About The Last Bongo Sunset (reviewed just ahead of A Void by Georges Perec) The New Yorker said, “For the narrator of such extravagant, ravaging prose, it would be impossible to commit a cliché.”

But now that book is long out of print, and Les’s last two novels reached only the circles already aware of his work. What would ever become of the Hungarian novel, all these years in the making?

Shortly after Les’s death, as friends and students wandered in dazed disbelief, the Australian novelist David Francis—a former Plesko student and protégé—seated me next to an editor from Counterpoint at a PEN USA dinner. David knew that the story of our colleague’s death and the tragedy of No Stopping Train soon would arise in conversation, and so it did. The editor, Dan Smetanka, was eager to see the manuscript. Who had the book? When could he read it?

Word went out. Les, a great letter-writer, had sent various incarnations of the book to his correspondents over the years, notably to Julianne Cohen, to his former fiancée Eireene Nealand, and to his devoted student Jamie Schaffner. All of them were able to produce incarnations of the manuscript. Soon Les’s younger brother, George, received an offer to publish.

So comes the end of a very long journey for one small jewel of a book. It is with a profound and bittersweet pleasure that I now hold this volume in my hands. How proud Les would have been if he had lived to see this day, how happy he would be for you to turn the first page.

I wish you good reading.

JANET FITCH

Los Angeles, California

April 21, 2014