Читать книгу No Stopping Train - Les Plesko - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

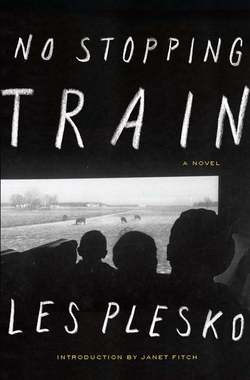

ОглавлениеThe rails curve away from old rain. Beneath me, the river draws earth from the banks, gorges itself on mud, stones, rain-swept leaves. Every place the train passes I think, we could have lived here. Milked goats, sap from trees. We could have cured sausages in these curing shacks, watched the progress of fat dripped in pans, the honeycomb ooze of nectar we robbed from our fat yellow bees. We could have forsaken our gunmetal press, the tindery papers we printed that burned up your hand.

But I don’t know farms from carpets, bees from nicotined nails, yellow teeth. I know Budapest. In the city I was always crossing some dead hero square, some stranger’s mended clothes in a sack by my legs.

When we buried Alma the sky was like this.

I smelled you on me as they lowered her in. We’d made love while her body thawed on a slab in the morgue only two blocks away. I’d never been so reckless. Her death papers crumpled beside us in bed, you hadn’t had time to remove both your shoes, your hands were still blue from the press.

You touched my shoulder at the grave but I fled. At the top of the rise, they were burying somebody else.

Should I say why she murdered herself?

Seven winters she waited for him, watching the top of the tree, down on the sidewalk, the useless affairs of the weeds. Yellowtooths lay disarrayed, dug up by the usual dogs. She didn’t waltz the broom, sweep. She paced across fingernail parings, dry crusts, wrote my father’s name in the dust, breathed the lack of his hands. The expectation of his steps in the hall, the icebox’s drip, the faucet’s wet tick were her clock.

Her sweaters had holes in the elbows where she leaned and leaned. Her feet hurt, she had to lie down in the cold lardy night, unsure where her bones pressed parquet and the hard floor began. Her palms filled with dark then with light until she forgot what all the waiting was about. Sometimes she got so small in herself she hardly dared to cough.

Was she sad?

Listen, she chopped off her hair from regret. It used to fall in her eyes, just like mine. When she ventured outside, she must have tried little slips on the ice but felt my father’s absent hand grab her arm. Maybe she made that small speech I had heard: “If I’d twisted a shin, broken a wrist, we could have gone to the clinic instead of the altar,” she’d said.

Sometimes I rode by on the tram, sometimes I got off. She said, “Everyone’s getting married again, everyone has come back.” She opened her window, looked down. “Don’t joke with me, Margit, not coming home, who gave you permission for that?”

“But I’m here right now,” I replied. “See? Do you need anything? Are you doing all right?”

One day there was nothing out there except what had always been there, the bakery, the milliner’s shop. Nothing disgraced our Saint Matyas Street except what had always shamed it. In the war before last, she knew where the bodies were stacked for the carts. Your father used to load them. Right on the corner, Germans rinsed helmets, boiled soup you could sell yourself for. Blond hairs floated on top, Alma said, blood-rust flakes in a blue helmet bowl.

She must have thought it might as well be 1917, 1918 again. She must have believed the dead were twice blessed, finally blameless and they got to visit the rest of the dead. She grew tired of her nails and her hands, expecting me or her husband my father or bells, the toothachy pull of cigány violins. Maybe she thought snow, about how to get there.

While I tromped up the stairs through Christmas, New Year’s, her birthday remembered, her name day forgot. I bore insignificant gifts, hard candies, chicken wings, spent nylons robbed from clotheslines.

“It’s worse when you come,” Alma said, “then you’re gone and I have to remember I’m getting accustomed to it.” She might have waved at my retreating back, but I wouldn’t know, never turned, didn’t stop.

Then nothing was out in the street but a soldier, a fountain, a blue-smoked Trabant. The air had the smell of horse droppings, wet dogs. Her hair had the odor of cigarette smoke, my hasty visit in it. Her room had her lying-down scent. She thought, years of this, my gray hair growing out.

She’d miss it, she thought, but not much. Perhaps she’d be missed for a while, but that wasn’t for her to decide. Downstairs, the door yawned. The wind blew the door open wide, it always did that. She buttoned her nightgown, she put on her shoes, her good dress so it might be appreciated at last. She did not turn around. Her heels on the stairs made her Tilt-A-Whirl queasy, a little knee-sick, thinking, here’s how I leave, a shallow-pressed shape on a bed, a name written in dust on the sill.