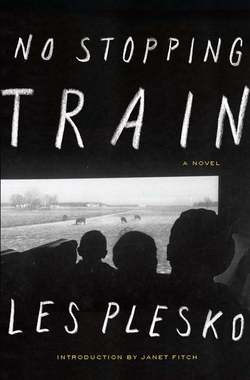

Читать книгу No Stopping Train - Les Plesko - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTrees pass by the train tracks, I guess oak or elm. A city girl, I don’t know names of trees from lampposts. I know my mother’s names for resilient weeds that grew up from Budapest’s sidewalks, green puff, yellowtooth.

Last time I saw Alma alive was a day like today. So many days in this place are exactly the same.

Outside the Saint Matyas Street house, rain turned the corner and fell. The rain through the window frame gap on parquet was a clock in a dream you wake into again and again. My mother, myself, just like it had been in that place since 1938. We stood by the glass, our same-sized palms pressed to the pane.

“It’s just like old times,” I said.

In the winter-burned tree, weather-beaten birds hid their wings.

“Old times was only last week,” Alma said. She wore the nightgown I’d left her in. Afternoon light struck the cloth.

“I’ve fallen in love since last week,” I replied. Almost a whole year had passed, but I hadn’t dared mention it, just in case it was my fantasy.

“Love is a bad accident,” Alma said.

Accidents made me think of you, Sandor, the bruises you left on my wrist, the kisses you pressed on my cheeks. Those reflections of blooms I had touched in our mirror’s cracked wedge had made me misbutton my red poppy dress. Even now my shoes fill with silence just thinking of it.

“He’ll leave you with nothing to show but his smell on your breasts,” Alma said.

Thank God for cigarettes. I lit one and hugged your velveteen jacket to hide our bed scent. In my mother’s house, my smoke drifted up, stung my eyes like the cheap sentiment of some future regret. “That man doesn’t hurt me,” I said like I almost believed it myself, though I sat up nights waiting for you, peeling the soles of my shoes while next door a husband and wife slapped each other around and I touched my face from their blows, listening for footsteps.

“If he didn’t hurt you, you wouldn’t have come around,” Alma said. She fingered her nightgown’s scooped neck.

“Hurt’s all right when before there was nothing,” I said.

Alma’s mouth tugged in a smile only I recognized. “On our wedding night, I wouldn’t allow your father in our bed. I reached down to the floor where he slept, but he never once took my hand.”

“That’s not how it was. He reached up, you refused, he told me,” I said.

She leaned on the sill, looking out at the gray scuddy muck of the sky. “We walked to the church where we wed. Your father kept saying my name as if I would forget it,” she said. “We ate Dobos torte on a bench by the opera house steps. He brought lilies, three hundred forints a bunch. I wore kidskin gloves. Snow fell all over his new silk shirt, ruined it.”

But what I recalled was how during the war my mother had purposely shut all the windows to blow out the glass. Death was the natural order of flesh, she had said.

I said, “Why are you telling me this?”

Alma rubbed her hand where her wedding band had once been.

“Because you’re in love and you think you can do anything,” Alma said.

I studied my nails so she wouldn’t notice the blunt satisfaction that must have been plain on my face. “You envy me because I’m not like you,” I said.

Alma laughed. The jut of her hips through her gown in failed light made me sick.

Now my shoulders are holding my coat, my hair holds its barrette. My body is winter, a dark train car lit by my white hands. My hand is a glove my mother once wore. Her glove in the snow is the color of rain. My arms are crossed over my breasts, my face crossed by cigarette smoke. My eyes wet as the day, I stuff newspaper pages into my shoes for the cold. The rain is as damp as my father’s corpse left to rot at the front. As our room where my mother and I touched shoulders by accident.

“You made him run off to the war, you killed him,” I said.

Neither one of us spoke while we considered this. Alma’s eyes became shiny and hot. Her shoulders described a practiced weariness I felt down my back, in my arms.

“That wasn’t me, love did that,” Alma said.

I’m half my mother’s age when she died. In the cool future I see myself in a city with awnings and atomic clocks. It is a different country. Women don’t wear these cheap polka-dot scarves, men don’t wear hats; if they do, they don’t wear them so low on their heads.

When I arrive, I’ll recognize her in the wan armature of my stance in patisserie windows I pass. I’ll be admiring some fluffy confection and I’ll have a sudden nostalgia for lilies that I never had. If it’s a place far enough, sunlight will flail my white bed, its thin sober warmth, my hand hanging over the edge. I’ll call this good, and no one shouting infamous names in the square, the newspaper carrying no five-year plans or decrees. Obituaries will reveal only natural deaths. But this will mean nothing to to me, I won’t understand the language.