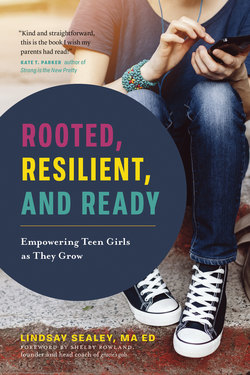

Читать книгу Rooted, Resilient, and Ready - Lindsay Sealey - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWHO SHE IS BECOMING

SELFIES. NETFLIX. MUSIC. Spotify. YouTube. Hanging out with friends. Ripped jeans and sneakers. Scrolling through her social media feeds: this is your teen girl’s world. Pleasing, performing, and perfecting: these are her challenges.

Undoubtedly, by the time she turns thirteen and is officially entering adolescence, she has already been doing more on her own, wanting to spend her time with friends, and showing early signs of “teenager rebellion,” such as boundary pushing, especially when it comes to household rules around curfew, clothing, and screen time. Yes, she is likely doing some eye rolling and offering up a little sass, telling you that you “just don’t get her” while her strategically positioned hand rests on her hip.

And yet, “getting” a young, impressionable teenage girl is no easy task. It’s difficult to determine who she is becoming because she is in a state of constant flux amid chaotic societal influences. Some girls seem to be clear on who they are and are confident enough to tell me what makes them unique, like fourteen-year-old Ayisha: “I think my voice makes me unique,” she said. “Many people say that I’m too loud, but I think they are too quiet.” Other girls showed more doubt—like Morgan, who shyly responded with typical teen upspeak, “I think I am nice and caring?” When I interviewed eighteen-year-old Laurel, a girl with an incredibly calm demeanour and a light sprinkle of freckles dusted across her face, she quietly reflected, “It’s funny when you look at pictures of your younger self, thinking that you knew it all.” Girls often feel more grown up than they are and feeling that way is part of growing up.

Psychologists tell us that the two most fundamental milestones of adolescent development include understanding identity and gaining social acceptance—knowing who she is and feeling she belongs. As girls are figuring out what roles they play, such as daughter, sister, friend, student, and teammate, they are also figuring out themselves: their interests, hobbies, qualities, likes, dislikes, and beliefs. During this dynamic time, teenage girls are perpetually changing, developing, and learning, and are deeply engaged in the maturation process. According to David G. Myers and C. Nathan DeWall, “adolescence is a time of vitality without the cares of adulthood, a time of rewarding friendships, heightened idealism, and a growing sense of life’s exciting possibilities.”1 Adolescents don’t know everything, but they are beginning to know something, especially that their lives are filled with a combination of exhilaration and angst.

A growing teen girl’s identity is shaped by many factors and is the culmination of her values, interests, beliefs, personality, and “place in life.” She is becoming herself through the interactions she has with others and the feedback she receives. Keep in mind that her brain is developing. Teen girls experience the most dramatic brain growth in adolescence, during which there is an increase in brain matter and the brain is becoming more interconnected and gaining processing power. In her early teen years, her brain relies more heavily on the limbic system (the emotional centre) than the prefrontal cortex (the rational centre). As your teen girl grows, other parts of her brain are able to process emotion and she is more able to be calm, rational, and reasonable.2 Eventually, the sometimes-exaggerated emotions of middle adolescence will become less intense and more balanced as she considers who she is and absorbs the broader perspective of who she is becoming.

Parents have the privileged position of watching as their teen girls grow into increasingly independent and mature young women. Many a parent has shared with me their wonder over this transition. (“I felt so proud watching her positive energy with her friends on their way to the concert,” for example.) But parents also tell me how, at times, watching the growth process can be difficult. So many changes are happening all at once, and there are changes they didn’t anticipate. The toughest part for parents seems to be dealing with disappointment around who their teen daughter is becoming. You may have hoped she would be an athlete, but she would rather draw and work on her art. You may have wanted her to be social, like you, and enjoy a large and eclectic circle of friends, yet all she wants is alone time in her room, where she can be absorbed with her imagination or her smartphone. You may have imagined her wearing skirts and dresses, but her style is pants and her older brother’s hoodies.

When parents feel that their expectations are not being met or that their daughter is not living up to her potential, they typically try to help. Unfortunately, that “help” often comes via limiting language, which can cause frustration. A discussion about career choices could include a statement such as “You really don’t want to pursue hair and makeup; there’s no money in that.” Or a chat about an extracurricular passion might end with “Honey, you’re just not the musical type,” or “Perhaps you should let someone else take the lead in the school musical.” Your intention may be to help her “be her best,” and even to protect her from any hint of disappointment, but what she’s hearing you say is this: “You are not good enough as you are.”

You want the best for her. You may even want her to have a better life than yours. But she needs to choose a life of her own. One of the most important things I hear from teen girls—and I hear it often—is that they need you to accept their choices as they figure out their uniqueness.

Helping your teen girl explore her identity begins with letting go of any preconceived expectations of who you want her to be. In doing so, you can give her the space she needs to step into who she truly wants to be. In the quest to be supportive, parents may inadvertently tell girls who they should be, especially when applying labels or offering guidance or limitations: “You are quirky,” or “You have a dancer’s body,” or “You need to put more time into science so you can get a good job in that field.” This may cause confusion. Labels can feel like boundaries, but she may nevertheless sacrifice herself to fit them. From a brain-development perspective, her connection to you is her lifeline.3 Most girls will do anything to keep that lifeline of attachment open, even if it means bending to meet parental expectations. Essentially, she will be who she thinks you need her to be in order to alleviate fears of separation and disconnection.

What if you don’t like who she is becoming and your knee-jerk reaction is to steer her in the opposite direction? This is when you need to be calm, centre yourself, and change your approach. Remember, periphery parent. Be ready to guide her, not control her, by asking questions about how she’s changing and if she is happy with the person she’s becoming. Try asking, “What do you like best about yourself, or least?” Consider offering her this compliment: “I love how (kind/confident/competent) you are becoming.” When we tell girls who we want them to be and place them in categories, we hinder their quest for authentic identity. Instead of being in denial about who she is becoming (“My daughter would never be bisexual”—despite the fact that she’s mentioned having both boy and girl crushes) or being dismissive (“Her interest in playing the drums is just a phase”—even though she’s been practising for years), we help girls tremendously when we accept what they show us. Ultimately, when we accept her, she learns to accept herself.

SAMI

I actually don’t like it when people over-identify with any one aspect of their identity. It bothers me. Even with people who are part of the LGBTQ spectrum and only identify with that part of them and I know there has to be more to them. There is so much more to them. That’s one of my pet peeves. I try not to over-identify with any one part of me because I know there are so many aspects of me. All of our different parts fit into a puzzle, and I acknowledge that all those pieces are there and they make up a picture that is me. To take any one of those pieces and focus too hard on it is not really respecting all the other pieces and allowing myself to be the entire puzzle.

I am light-skinned but I am half black and I am treated as the acceptable token black person. I am “ethnically ambiguous.” When people ask me, “What are you?” I know it’s such an inappropriate question. I am not denying myself but I know how to pull on different aspects of my identity when they serve me best. It’s similar to code-switching, which a lot of people of colour have to do. They have to know how to talk to different groups in a different way to be taken seriously. Women have to do this as well. They can talk to their friends a certain way. But when they talk to their bosses or men, they have to speak differently to get their point across.

Her Centre and Circles of Influence

Identity is a tricky concept to unpack, as these teen years are all about growth, movement, and expansion. I view a teen girl as surrounded by a series of concentric circles representing her genetics, family, peers, and her culture and society. Your daughter is standing in the centre of her own circle surrounded by these circles of influence, all of which may exert pressure and constantly reflect back to her a version of “who she is.” As she learns to stand strong and rooted in her own circle, she feels the competing interests and allegiances between these circles. At best, she will deal with the pressures by setting firm boundaries and becoming more secure and certain in her own choices and decisions. At worst, she will give in, give up, and yield to the pressures around her. This may result in her feeling deflated, disappointed, and, most likely, lost in her identity.

We need her to feel shaped positively by surrounding circles of influence but still free to discover who she is, in her own way and in her own time. For when she stands inside her circle, she is rooted in her strengths and capabilities, and she is strong and secure. She will not be pushed out of her own circle. She knows she has the right to be standing there. She owns her space.

As described in the introduction, you are standing in a supportive role as a “parent on the periphery” (p. 6), but you are also closest to her centre. Now is the time to view her identity on a broad spectrum of possibilities rather than through a specific definition or role. Nothing will feel better to her than knowing you are there—with an open mind—if she needs you, and that she has your full support and space to grow. The world will try to tell her who she ought to be. Your message to her must be louder and stronger: “You do you.” The knowledge that you have her back will safeguard her against any insult or pushback she receives from others. Your assurance that she is the centre of her own circle will serve as a defence against other circles that have the potential to distort her true identity.

Therapist Tiffani Van Buckley told me that when it comes to teen girls figuring out who they are, the greatest challenges she witnesses are judgment from others and self-judgment. When I asked her to offer one piece of advice to parents who notice teen girls struggling to accept themselves, she said this: “Practise acceptance of who they are rather than impose ideas of who they should be.” Teens girls are tough enough on themselves. Let’s just see them for all they are in this moment. Let’s validate the good stuff and suspend all judgment.

Genetics—How She is Born

Identity is an ongoing and multi-faceted aspect of a teen girl’s journey; how she is born is simply the beginning of that journey. The influence of genetics unfolds in the womb in that DNA will determine her gender, eye colour, height and body type, and potentially her behaviour and personality. DNA also dictates the health of her genes, her genetic predispositions, and her cognitive functioning, including possible brain-based disorders (such as attention deficit hyperactive disorder, attention deficit disorder, sensory processing disorder, or autism spectrum disorder), anxiety levels and responsiveness to stress, and physical disabilities. Some girls will be born with a genetic advantage such as intellectual giftedness, artistic or athletic prowess, or some other kind of talent. A few girls will win what Cameron Russell, in her TEDX Talk, called the “genetic lottery.”4

Some girls don’t feel like girls at all. New research on transgender or transfluid individuals now shows that there are differences in hormone levels in the brains and bodies of those who feel they don’t match their DNA. In an interesting article in The Atlantic, Jesse Singal explores the complications that can arise when teens identify as transgender. For parents, this identification often results in great uncertainty. Is it the result of an intensified search for identity in the uncertain years of adolescence, or of exposure to internet articles and YouTube videos? Or is the identification an indicator of an actual conflict between their child’s gender identity and the sex assigned at birth?5

Whatever your child’s genetic makeup, you have the most influence when it comes to helping your teen to accept what she was born with, without shame or blame, and then move forward. You can do this by telling them, “How you are born is out of your control, never your fault, and what you have to accept.” Then reassure them that “what you can control is what you do with your genetics,” and that this begins with embracing the fact that we are all unique. Girls can get stuck on labels (such as being anxious or ADD), and their fixation inevitably limits their growth and damages their self-esteem. Encourage girls to expand their view of themselves and their circle by first acknowledging what holds them back. Meet them where they are in their struggle. Connect before you redirect the conversation. Then you can ask, “What else you got?” This will prompt them to consider themselves beyond their genetic fate. You can acknowledge that she may feel she is simply “not a writer,” but you can also help her see that where she puts her focus, time, and effort is where she will develop her skill set, whether we are talking about mathematics or socializing. This is what matters most when it comes to her growth and progress. The approach is all about widening the circle of her self-perception.

Family and Life Circumstances

Teen girls live inside all kinds of families: biological, adopted, foster, blended, single-parent, double-parent, two moms, two dads, and as many differences within families as between them. Some families have greater financial means; others struggle to make ends meet. Some families are dealing with addiction, health concerns, and even extreme circumstances such as abuse and incarceration. Some girls are born into order and peace, while others are born into chaos and drama.

All families function differently, depending on family values such as integrity, curiosity, loyalty, respect, and kindness, as well as family traditions and rituals. Communication styles vary too. Some family members speak about feelings and concerns in an open and honest way. Others tend to avoid or deny feelings and important conversations. All families also have ancestral history, behavioural patterns established long ago that a teen girl is often not privy to until she is older.

No matter what circumstances she is born into, family can have a profound effect on a growing girl’s identity. Family can push her with the encouragement she needs to take a chance when scared. It can also pull at her with demands and responsibilities for which she is not ready: “As the oldest, I expect you to be in charge.” Yet a girl can reciprocate by doing some pushing and pulling of her own: simultaneously pushing family members away so she can go it alone and pulling them close for comfort and familiarity. Parents often speak to me about this confusing “I need you but I don’t want to need you” experience. Believe me, she feels as confused as you do! Some girls tell me that their parents “just don’t get” them or “are so overprotective and ask way too many questions.” But other girls surprise me with comments like “My family will be there for me in a way friends can’t be,” or “Even when I totally mess up, my parents still love me.”

What’s happening here is that your teen is testing your boundaries to see what she can get away with and if your strength and security can keep her safe. She is also learning to fact-check you—more to prove she can think for herself than to prove you wrong—and to cross-check family beliefs and values with her own. Family can be her rock, a place where she feels most like herself and where she can unburden her stressors. But family can also be a source of stress, forcing her to be someone she is not. The conflict between wanting to be independent and yet needing to feel dependent on family is deeply felt by many teen girls, whether they are fourteen or nineteen. It will take some balance from you to show her how to balance that conflict in herself.

Choice and Voice

The teen years are tricky to navigate when it comes to family. You may want to continue with family time and the “way things were,” while she is eager to break free from “jail.” You’ll need to find compromise and balance. Living in your home, she’s still expected to have chores, duties, and responsibilities. A teen girl trying to figure out who she is as a separate entity from her family will need more choice to use her voice. Choice and voice in the family home will build up her self-confidence and her self-worth, both of which will serve her well outside of the home. Here are some ways to provide opportunities for her to practise using her voice:

•Ask her opinion about dinner and weekend plans, and delve deeper into current events and social issues. She may instinctively say, “I don’t know,” but give her time to consider and ask what she does know.

•Encourage her to examine her opinions and state why she thinks what she does. Listen and stay open-minded. Say things like “I want to understand where you are coming from. Tell me more.”

•Avoid assuming that she is unaware of various topics or dismissing what she says as uninformed.

•Assure your teen that she can tell you anything—and mean it. Show her you are available and ask questions out of curiosity, not judgment.

•Be inquisitive about what’s below the surface. Ask, “How was the party last night? Was it what you expected?” Or “I notice you’re putting in a lot of time on social media. What kinds of posts are you seeing?” Or “You seem quiet lately. I’d love to hear what’s on your mind.” When you ask creative and open-ended questions—questions she may not expect from you—you invite her to share.

•Respond with understanding and encouragement when she offers you an insight into her world. Even if you are shocked by what she says, remain calm in your response.

•Refrain from assuming she doesn’t want to talk; she may not know how to get her words out. Giving her choice instead can help: “Does your ‘I’m fine’ mean you are, in fact, fine, or do you need more time to consider how you are doing?” (Sometimes “I’m fine” actually means “I really want to share with you but I am afraid you will react or overreact.”)

She’ll talk when she’s ready, and you need to be ready and available for these occasionally rare moments. Conversations can be had around the dinner table, or during rituals parents commit to, such as Saturday morning breakfast at her favourite cafe. But more likely these conversations will happen spontaneously: in the car on the drive home from soccer, just before bed when you say a quick good night, or when you find her lounging across your bed with her iPad. Remember: your frustrations about her choice of clothing or friends, or undone chores and homework, or myriad other things you fight about are not the conversations she wants to have—they distract from the real stuff, the good stuff. She wants to tell you how afraid she feels to go to PE class and about the rejection she sometimes feels in her peer group. But she can’t get there until she feels safe and ready. Most of all, a girl needs to know that her decision to create a life better than the one she was born into is a positive step forward. She need not feel guilty or ashamed. Family circumstances do not—should not—hold her back from who and all she wants to become. We can tell her this!

The Effect of Peers on a Teen Girl’s Identity

I’ll talk more about the influence of peers, for good and bad, in chapter 6. Here, though, I want to explore the effects of peers on a teen girl’s identity, as these are formative influences. There comes a point in every teen girl’s life when she likes spending time with her family a little less and time with her friends a little more. This transition period from the comfort of home to the new and unfamiliar social world can be easy for parents who choose to let go and more difficult for those who choose to cling tighter, filled with worry and trepidation that pressures from peers are too much for their little girls.

Without a doubt, her friends are now influencing her far more than you can. You may not like her friends or even know them. Gone are the days of scheduling play dates and chatting with other parents to confirm (and vet) them beforehand. She’s making her own choices now and it’s tough to watch, especially when those choices are not healthy, when she gives up who she is in order to be accepted, and when she is so worried about fitting in that she forgets about herself. The truth is that her identity, her values, her interests, her habits, and her self-worth work in close connection. She is learning important social mores, such as letting her friend finish her story before offering her own opinion, and the unwritten social rules of girlhood, like sharing exciting news with confidence but not conceit. Other girls will call her out on unacceptable social behaviours, and she will learn quickly. But right now, she needs others to understand both her own identity and how to behave.

She will start sorting out whom she wants to spend time with: Someone like her, with shared values and interests? Or someone not like her at all, so she can learn to step outside of her comfort zone? She is figuring out who she is in relationships, what kinds of friends she wants in her circle, and what kind of friend she wants to be. And she’s wondering where she belongs: Is it with the cool girls, the girly girls, the sporty girls, the creatively artistic girls, or the girls who have formed a group because none of them belong anywhere else? Fourteen-year-old Sierra, with tight blond curls and a bouncy personality to match, told me, “Trust is one of the most important parts of friendship. You need to know who you can count on and who will keep your secrets, no matter what.” Finally, your teen girl will have to figure out who she is amidst confusing friendship tactics like exclusion, boast posts on social media designed to activate her fear of missing out, or the silent treatment. As twenty-two-year-old Mila, who is now pursuing her college degree, shared, “Friends can be the best and worst. They can come into your life at your worst times, but also leave you at your best.”

Girls I speak with love having a group of friends that they feel build them up and embolden them to be brave. Friends help them to feel “normal” when they share common interests, hobbies, opinions, and worries as well as an emotional connection. But girls also feel deeply the pressures that come with friendships: to dress like other girls, to talk like them, to be interested in the same things, and to even share the same tastes in music and celebrities, even if that means not being true to themselves (see chapter 6 for more on peer pressure). Although there is safety and normalcy in sameness and conformity, girls also often reveal how much they wish they could “do whatever I want and not be judged.”

I met Emma when her mother reached out to me for help with Emma’s social skills. Emma had no real friendships at school and was labelled “weird” in the worst sense of the word, as in “weirdo.” Emma had slowly separated from the other girls in her class, with whom she felt she had nothing in common. Instead, she began to solidify what she loved to do: she biked to school instead of getting a ride, like the other girls; she brought her lunch to school in recyclable containers instead of buying one; and in class she would speak up about feminist issues, while avoiding chats with girls about boys and weekend plans.

I was challenged because I did not want to confuse Emma with a mixed message: be yourself but change to fit in. As we got to know each other better, I affirmed all the times she used positive social skills, such as asking questions, listening and responding to some of my comments, and complimenting me. Emma was less strong in social skills such as showing empathy, connecting with others’ feelings, and taking the time to understand or even learn from an opinion different than her own. I loved that Emma was herself, and I told her so frequently. At the same time, I helped her develop her social skills so that she could have “the best of both worlds.” I’ll never forget the joy that spread across her face when she told me how the other girls were starting to ask her questions about riding her bike to school and some of her passion projects around social issues.

Girls do know that their identities are being shaped by people they spend a lot of time with, and they do struggle to find their unique identity within the group culture. Just like Emma, they want the best of both worlds: enough conformity to feel “normal” and enough authenticity to feel “special.” Girls long for this kind of balance. Yet research shows us that despite their best intentions to be independent thinkers and have unique personalities, when the choice is between staying true to their voice or giving in to the group, most girls choose the latter because the fear of social rejection is debilitating. A teen girl often feels she does not have a choice between these two poles—she either agrees and gives in or is ostracized, also known as social disaster. The desire for belonging is so great that a teen girl will do anything—and I mean anything—to belong, even if she knows the danger of surrender means losing herself in favour of pleasing others. In other words, she will shape-shift, or be defined by and shaped by other people. I will talk more about how to help your teen girl avoid this pitfall later (p. 42).

Your daughter’s experiences in friendship are where you will see the most experimentation with her personality. Depending on the group she is hanging out with, she may be mean or bossy, sweet or quiet, hyper or crazy, quirky or calm. You may drop her off at school in the morning sporting one personality only to pick her up in the afternoon trying out a new one, complete with its own vernacular and attitude: “Mom, you totally don’t, like, get it, but you need to take me for sushi. I’m staaaaaaarving.” This imposter may not be the daughter you waved goodbye to in the morning, but never fear: she will be back, once she figures out how to sound more like herself.

What you can do is keep an eye on her, be curious about her friends, and check in with her about how she’s feeling after spending time with different people. Ask her what qualities are important to her in friendship and remind her that you trust her. Tell her to listen to her gut and trust her feelings about which friends are best suited to her. For instance, you can ask, “What do you like best about Zoe?” Or “I notice you giving up a lot to do what Sophie wants. What does Sophie give up for you?” We can help girls pay attention to their friend experiences in order to gain a better understanding of some fundamentals of friendship—namely, respect, reciprocity, loyalty, and care. If a friend doesn’t fit her standard, then empower her to let go and move on to new friends.

The worst thing you can do here is project your fears onto her. Tell a teenage girl who she can’t hang out with and she will often purposefully defy you by making her casual acquaintance her new best friend forever (BFF). She will see you as a controlling helicopter parent (yes, she knows exactly what this is), and she will hate you hovering over her when she is trying to figure out who is in her circle. I beg you, don’t be a helicopter. At the end of the day, most girls do find their way through the “spring cleaning” season of friends, and they understand that those who surround them are shaping them. Again, this is her choice, not yours.

Culture and Society

The final ring in the series of circles surrounding your teen daughter’s centre is culture and society. The world—society in general, but social media specifically—is constantly telling your daughter who to be and how she should be defined. She is categorized by gender, sexual orientation, race, religion, clothing and style, body type, lifestyle choices, socio-economic status, education, and achievement. Concurrently, she is influenced through music, music videos, video games, movies, social media sites, television, magazines, books, billboards, celebrities, online sensations, and advertising. Marketing companies target youth by sending them a mixed message: “Be anything you want to be,” but “Be this kind of beautiful and this kind of successful.” These companies are also selling brands and products to “help” improve our impressionable girls, while simultaneously teaching them that more is better (you can never have too much) and you gotta have it now (why wait?). This is smart from a business perspective—it plants the seeds of consumerism for future buyers—but it is damaging to teen girls’ self-worth. How influential is media and social media on your teen daughter? Research tells us: very.6

Everywhere girls turn—whether to the online world or a concert featuring their favourite indie band—the message is loud and clear: be what the world tells you to be. Girls absorb the societal pressures to be good at everything, which results in the “supergirl syndrome” of trying to be super-powerful, super-strong, and super-talented—and making it look effortless. What girls may not know is that in striving for perfection they are undermining their own self-confidence as their stress skyrockets. Girls feel the demands of social stereotypes acutely as they find themselves trapped in a box that, all too often, they did not choose.

Societal messages are noisy, incessant, and often unrealistic and unhealthy, especially when it comes to body image (see chapter 2).7 The often-competing messages teen girls receive are cause for parental concern. She needs time and space to hear the quieter voice within, guiding her to follow her own path. You do not want her voice to be dimmed or silenced. So how can you help to protect your teen girl from warped societal and cultural messages? Can we undo what she’s already been brainwashed to believe and reteach her more positive messages? Yes. What I know is that girls need to be both positively inspired and positively influenced. Here are some ways to do this:

•Maintain ongoing conversations with her about limiting her screen time, as what she views is what she will see as “truth.”

•Provide competition for screen time by planning activities with her. You won’t get her to give up her phone entirely, but you may be able to entice her to go to a movie or the newest clothing store.

•Explore your own social circles for healthy role models. Look for a family friend, an older cousin, or an aunt willing to spend time with her and provide a powerful example.

The Masks of Her Identity

When adolescent girls feel they need to shield their authentic feelings and identity, they often reach quickly for a mask. A mask can serve them well when they are feeling vulnerable or deciding whom to trust. However, masks also keep girls distant and disconnected not only from others but also from themselves. And, if masks are worn constantly, girls are at risk for mistaking the mask for who they really are. If you think your teen girl is hiding behind a mask, the best way to help her lower it is simply to notice it, and then to be curious and slowly encourage her to reveal her true self.

In Growing Strong Girls, I discussed both the mean girl and the good girl facades: the former excluding, degrading, and tormenting other girls to gain a sense of power and dominance; the latter acting as the obedient rule-follower, who is an expert at keeping up appearances and being, well, “good.” Each persona serves as a disguise for the real girl who desperately wants to be included and accepted. In many ways, masks provide the perfect disguise for a teen girl seeking (even subconsciously) to protect her identity and safeguard herself from her ultimate fears of being known or misunderstood.

Let’s explore three different yet equally common masks teen girls wear: the supergirl, the invisible girl, and the cool girl. It’s important to note that girls can adopt all of these masks at various times, or none of them. Perhaps she wears an entirely different mask. In my experience, however, these three tend to be the most common.

The Supergirl Mask

The supergirl mask is conspicuous: she is the girl who does it all. She’s active on sports teams, involved in school and community activities. Not only is she a member of clubs, but she is also a leader—and don’t be surprised if her supergirl awesomeness extends to responsibilities in the home. Likely she is the eldest sibling (or appears to be) and agrees to cook dinner, babysit younger siblings, while still having time to do her homework and complete bonus projects. She’s ambitious and driven, and her achievements are outstanding. Still, I can’t help but wonder if the mask of achievement isn’t covering a deeper drive to prove her worth instead of knowing her worth. The fear of being “nothing” is so great that she pushes beyond her boundaries to achieve, but she is frequently left feeling stressed out, exhausted, and empty. What she often fails to see is that even supergirls need to recharge, and that there is a difference between wanting to “do it all” and feeling she has to “do it all.”

The demands on a supergirl are many—be productive, be ambitious, be competitive, keep up, stand out, and do something to make your life count. In her head she hears, Don’t be mediocre, average, or ordinary. Be everything. These demands can lead girls to enter the cycle of perfection (p. 39). You can support the supergirl who is all things to all people by helping her to slowly remove her mask in two clear ways. First, acknowledge her efforts. See all she is doing and give her credit. Even better, ask her to reflect on her effort and give herself credit. When girls pause and look back, they begin to “get” all they are doing. Second, offer your support. Granted, she may not take it, but offer it anyway. I will ask a supergirl client if she wants to share what is on her mind, to offload her burdens. I write out every item she tells me is on her to-do list. Then we go through each item and come up with action steps to get the job done. In this way, she can see all that is on her plate. She can make the abstract stressors real and tangible while feeling more empowered to act and much less overwhelmed.

Supergirls are often happy being productive, and happy when accomplishing. My client Rose, for example, is gifted and excelling academically. She is also musical, the lead in her high school play, and athletic—she is on two track teams. Yet every so often she tells me, “I just have occasional meltdown moments where it all feels like too much to handle. I have a big cry and usually feel better and back to myself.” My experience has taught me that regular check-ins and talks where Rose can share can provide a release. Sometimes it is that simple; she just needs a moment to find her way back to balance.

The Invisible Mask

If the supergirl believes she needs to be everything, the invisible girl is convinced she is nothing. She fades into the background of life and blends in easily. She will hide in her hoodie, slouch, and offer little eye contact. At the first hint of discomfort—when meeting new people, for example, or being called on in class—she wishes for the superpower of invisibility. She may speak, but she’s apt to do so in a mere whisper and usually in a self-deprecating way: “Why bother going? Nobody will notice me anyway.”

Rarely will these invisible “nobodies” share their voices or make choices. The more you demand of her, the more frustrated you may feel, and the smaller she will want to become. Invisible girls are wearing the mask of “nobody loves me and I don’t love myself,” and they are covering up not only low self-esteem but also fading self-belief. They prefer to hide and be overlooked unknowns than to draw any attention to themselves. Granted, some girls are more shy and sensitive than others, and choose to be under the radar. But their “I don’t matter” mask is often covering up an internal scream: I want to matter and I don’t know how! Since these girls protect themselves well with their masks, they are often dismissed and discounted, which leads them to conclude that they are not important.

The invisible mask is a challenging one to remove; the girl who is wearing it is the hardest to reach, guarded and scared. However, it is possible to reach her slowly and patiently. Girls who feel invisible often want to stay that way. You can gently encourage her out of her shell by helping her to see herself in a more positive light. Seek out moments where she reveals anything—whether via a witty comment, a cheeky smile, or a one-off insight—and bring it to her attention. “Wow, that was astute.” Tell her repeatedly that when she reveals herself you really enjoy who she is, and encourage that girl to show up more often. Reassure her that she is most definitely a “somebody” and help her develop her self-belief by gathering evidence in her favour. Girls often do the opposite, building a case against themselves to prove how they “always screw up.” Comments like “See! You thought you could never order your own food in a restaurant, but now you do it all the time” are the kind of evidence she needs to hear. With practice she will learn to be less uncomfortable showing up as who she really is.

The Cool Girl Mask

Is your daughter always “fine,” indifferent, apathetic, often showing little interest? If so, she is likely masquerading as the cool girl—too cool to try, too cool to take risks, and too cool to take part in new activities. At the same time, she knows it all and has done it all. I often see this mask in place during my workshops. The girl wearing it is the participant who refuses to join in. She may opt for sketching instead of completing a handout. She may challenge a group activity by standing on the sidelines, offering up long sighs of exasperation coupled with dramatic eye rolling. If she eventually agrees to join in, she does so with an oh-so-dismissive “whatever” or the know-it-all phrase “I’ve done this before.” It is difficult to convince her to try anything because she is set on her intentional indifference.

The cool girl mask serves a purpose: to hide the fear of not knowing how, not succeeding, and looking foolish. Taking a chance on something new, and sharing her real feelings, makes her feel too vulnerable, so she becomes the cool girl and a powerful influence on her peers.

To encourage the cool girl to show her true self, you must be on her side, saying things like “I know this may not be your thing.” At the same time, you need to attune to her feelings: “You seem a little scared. Did I get that right?” Girls wearing the cool girl mask benefit from feeling understood and finding compromise. Link something she knows how to do, such as math, with something that is new to her and that she appears not to care about, like computer coding. Point out the connection—both require her trial-and-error learning skills—and be there with her as she tries. Cool girls need plenty of reminders to share who they are; they need to be shown, again and again, that people want to see the “real” them. Celebrate any time she steps out of her comfort zone and any steps of bravery she takes.

SONG-AH

For sure I wear the tough girl mask and definitely in sports because all my friends are in very competitive sports—like at the national level—in swimming, in soccer, and in softball. I feel like when I play sports with them, I try to be tough and pretend I know what I am doing because they are so good. I don’t want them to see that I doubt myself and feel I am not yet good enough at sports. It’s easier not to be vulnerable. When you are vulnerable you can get really hurt by people and they could make fun of you. If you act tough, people can’t hurt you. I don’t feel ready to lower this mask yet. I feel like it would be hard and I’d feel that people would treat me differently or exclude me. If I weren’t wearing the tough girl mask, I think I’d be happy inside that I don’t have to pretend anymore and also relieved—it’s a lot of pressure to keep it on! Actually, I’d be okay with it. Maybe I am not as athletic as some of my friends. Talent only takes you so far and then it becomes all about hard work and whatever I put my mind to.

Perfectionism and Inadequacy

Not good enough—three powerful and crippling words. Teen girls everywhere are feeling the “not good enough” epidemic, and it comes in many forms: not pretty enough, not smart enough, not popular enough, not sexy or skinny enough, not racialized enough, not rich or poor enough, not “normal” enough. The categories may take different forms but the memo is loud and clear when it comes to her identity formation: “You are just not enough.” The obsession with achievement and perfection is pervasive in our society—through advertising and online images, celebrity status, and even peer status—and this destroys a teen girl’s sense of selfhood. In Enough As She Is, Rachel Simmons writes about the damage of perfectionism in this way: “It costs girls their courage, curbing their ability to figure out who they are and what really matters most to them, exactly at the moment when this developmental task must be undertaken.”8

Feelings of inadequacy are pushing your teen daughter to be “better,” often beyond her own limits; they are also preventing her from honouring her unique identity. No surprise, then, that the more girls try to be “good enough,” the less worthy they feel and the more perfect they try to be—a vicious cycle.

All day, every day, girls see “perfect” in the carefully curated images on their social media feeds; they decide they need to be perfect too, believing this is their ticket to feeling happy, successful, and included. They strive for perfection: to be the perfect friend, to earn perfect grades, to attain the perfect look. And when they fail to reach these unrealistic ideals, they conclude there is something wrong with them—instead of realizing there is something wrong with the unhealthy societal standards that set them up in the first place. Unfortunately, a teen’s perceived failure will convince her to try harder, to be even more perfect. This cycle never ends because it is fuelled by deeply rooted seeds of “not good enough.” There is a direct correlation between the choice to be anything—or, for some girls, everything—and low self-worth. Perfectionism is an easy tool to grab to control the burden of inadequacy.

The cycle is damaging and destructive. You’ll see her push and punish herself, trying so hard yet never feeling satisfied, and showing not a hint of kindness or self-compassion. Many girls I work with are perfectionists, and we often start by deconstructing perfection. I want to give every girl a T-shirt that declares Perfect, just as I am or Good enough, as is. I often ask, “If perfect wasn’t an option, who would you be?” They pause and then come back with words like “free” or “happy.” Free to practise and progress, free to make mistakes, free to feel good as they take steps toward improvement, and free to be brave and take risks. Happy, just as she is. Once girls “get” that letting go of perfect may be a healthy option—an option that will also relieve them of enormous stress and strain—they come to an amazing realization: they can still achieve, but from a place of “I am enough” and self-confidence rather than from a place of “I need to prove I am enough.”

You can’t prevent your teen girl from absorbing cultural messages that encourage her to be “more” or perfect. You can, however, be proactive in delivering your own message: you do not expect perfection of yourself, and she should not expect it of herself either. We need to tell girls every day that they are enough as they are. By focusing on inner qualities such as her kindness, her compassion, and her willingness to try, we help her to focus on what matters most—her core values, not her achievements. This is not to say she should not strive for excellence. Excellence and perfectionism are not the same thing. Excellence is a journey of better and better every day, a gentle nudge for ongoing improvement that feels like progress. Perfectionism is an elusive destination that nobody ever reaches.

There are simple ways you can help your perfectionist teen daughter recognize that she is good enough as is. Tell her that you love her, just as she is, with a tender touch, a simple hug, and by simply being there. Yes, being there and the power of your presence is something, even though you may feel it’s not doing anything. Praise her while she’s working on her homework or a project and ask if she needs help. Ensure she takes the time to talk or just to have fun, to take her mind off her stress. “Not good enough” can become “good enough as is and getting better every day” for every single one of our perfectionistic daughters. Perfection need not be an inevitable part of a teen girl’s identity. In fact, we can liberate our girls from the quest for perfectionism by guiding them to let go.

All She Can Be

Five years ago, with clarity and intentionality, I named my company Bold New Girls. The “bold” stands for the confidence and bravery that we all want girls to feel. And “new” stands for the hope that every day is a new day—a new chance to embrace a fresh start and become all she can and wants to be, with neither the limits of the world nor the limitations she places on herself weighing her down. When a girl is “all she can be,” she is letting go of the idea of who she should be. She is letting go of pleasing and impressing others, letting go of searching for validation and approval outside of herself and instead seeking self-acceptance and self-love. She is lowering any masks she might be wearing to hide her true self and releasing any pressure she puts on herself to be perfect.

To help your teen girl achieve all she can be, I recommend you begin with a question of playful curiosity that I often use in my practice: “What if?” This poignant question dares her to imagine: “What if you were a little braver every day? What if you weren’t afraid of failure? What if you had that difficult conversation you needed to have, even though it was uncomfortable? What if you could be anything, and all possibilities were open for your taking? What if your identity and who you are are good enough—then who would you be?” When I ask these questions, the looks on girls’ faces often move from confused (good enough?) to relief (good enough!). They pause. They think.

Planting seeds with the language of possibility is crucial. Your teen girl cannot become what she does not know is possible, and she cannot know what is possible if it is not talked about. Once you help her imagine the outcomes, she can work backwards and start taking small steps toward actualizing her goal. Girls need to know they can embrace their identities despite family circumstances, school, and cultural and societal expectations. Teen girls need to know they can be what they choose: lawyers, designers, teachers, engineers, investors, inventors, moms, entrepreneurs, artists, or musicians. Your message of “you can be anything” must be louder and stronger than any cultural message.

From the outside looking in, a teenage girl’s world appears complex—and it is. But as you and she navigate it—you from the periphery and she from the inside—an amazing thing happens. With every step she takes, every stumble she overcomes, every choice and challenge she engages, she gains deeper insight and a broader understanding of herself. She is widening her circle; her identity is expanding beyond her initial expectations. She is taking time to listen to and then trust her inner voice, fine-tuning her intuition, living out her integrity and values, and showing the courage to own and share her story. She is learning to follow both her moral compass and her heart, as well as evaluating who and what is influencing her, how this affects her, what she knows to be right and true, and what she feels is best for her. This is what it means for a teenage girl to be rooted in her identity. And you can help her get there!

| How Parents HELP Growth •Showing support by parenting on the periphery of her circle •Accepting who she is becoming •Letting her choose who she wants to be •Showing genuine curiosity about her interests •Providing her with opportunities for choice and voice •Listening and being curious about her choices | How Parents HINDER Growth •Expecting her to be who you want her to be •Limiting her with labels such as “social” or “shy” •Deciding who her friends are •Being a “helicopter parent” •Believing the masks she wears are who she is •Pushing her to be perfect |