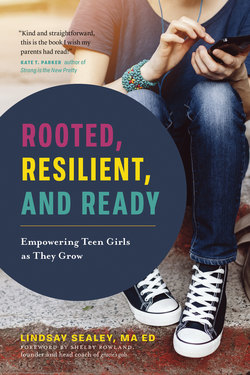

Читать книгу Rooted, Resilient, and Ready - Lindsay Sealey - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBEYOND APPEARANCES

I WAS A CONFIDENT teen. By the time I was sixteen, I had found my place in high school on sports teams, in band and choir, and with friends. I studied hard and earned good grades. Then it happened. One day, as I walked past a group of popular boys in the cafeteria, they called out, “Hey, Farms!” and followed it up with lots of snickering. At first, I had no idea that this unusual greeting had anything to do with me, but I became suspicious when this phrase kept popping up when I was around. I begged a friend to tell me what she knew. Reluctantly, she spilled the secret. “Farms” was a word they’d made up to merge “fat” and “arms”—and they were using it to refer to my arms.

Before this catastrophic moment, I felt beautiful in my body and was blissfully unaware of the normal weight gain teen girls often experience as they grow. I decided that my best weapon in fighting off these hurtful comments was retaliation—and this came in the form of self-neglect and, eventually, an eating disorder. I ate less; I ran more. I pushed, punished, and starved myself. Essentially, I developed an unhealthy coping tool to deal with life’s stressors. I thought my body was the problem and that changing my body was the obvious solution. Less obvious to me at the time was the underlying issue: my inability to love myself exactly as I was.

My challenge with holding a healthy body image emerged out of a lack of positive role models for how to love my body. Today, I want to share my experience with girls as a message: your bodies are not the problem. The deeper concern is the capacity to accept who you are and feel good about yourselves at any shape and size, and regardless of other people’s opinions. Looking back now, I feel incredibly sad for my teen self who didn’t know what to do with uncomfortable criticism and who was incredibly beautiful and healthy just as she was. Still, I am grateful for this experience. It inspired my passion to empower girls to be more preventative when faced with stress and strife. This chapter is all about body image—how deeply it is felt as a defining part of a teen girl’s overall image, and how it can be both a positive and negative influence. An adolescent’s view of her body can become convoluted so quickly as she grows and becomes more aware of what a body “should” look like. Girls are born loving themselves wholly and completely. We need to remind them of this and guide them back from self-loathing to self-loving.

Body Love and Loathing

“It’s a girl!”

Do you remember when she was born? Those chubby little thighs, round tummy, and teeny fingers and toes? What your daughter needed then was simple: your love and attention. She did not ponder if she should eat fast food for lunch. She wasn’t wondering how many calories she could burn at the gym later in the afternoon so she could eat the muffin staring her down at the bakery. She wasn’t stressing over every bite she ate, counting each calorie consumed. As a little girl, entrenched in the sensory experience of being and feeling, your daughter knew exactly how to love herself; it was natural and intuitive. At the age of ten, Alya told me this: “When I was younger, I felt as beautiful as a Disney princess.” I somehow doubt she still feels this way. Alya lives in a world that convinces little girls there is one physically superior look, a world where fifteen-year-olds such as Emma-Jane routinely say things like “I hate all the fat on my body. I don’t know why, but I do.” Born in love, learning to hate. So, what happens as girls grow?

As her parent, you may notice your teen girl’s emerging focus on the minutiae of her appearance, the drastic increase in her mirror time, the obsessing over hair, makeup, clothing style, and physique—more care, more conscientiousness, and more self-criticism. There are both biological and sociological reasons for this shift of focus to her appearance. According to Louann Brizendine, author of The Female Brain, when girls enter puberty, chemical changes to the brain facilitate this obsession with their looks. “The teen girl’s brain is sprouting, reorganizing and pruning neuronal circuits that drive the way she thinks, feels, and acts—and obsesses over her looks,” Brizendine says. “Her brain is unfolding ancient instructions on how to be a woman.”1 This speaks to the biological reasons why your teen girl may be obsessed with her appearance, but what else is going on? It’s possible that she may be mistaking looking good for feeling good.

Ginny Jones, editor of More-Love.org—an online resource for parents of children with eating disorders—asserts that a teen girl’s obsession with and criticism of her looks should not be looked on as normal or acceptable. She says:

We live in a culture that has normalized body hatred, and poor body image. This includes feelings of despair and anguish over the appearance of one’s body. When we hate our bodies, we believe they are flawed. Believing that the body is flawed, especially when one is physically healthy and able-bodied, makes us vulnerable to body hate, disordered eating, and eating disorders. What is actually “normal” from a health standpoint is body acceptance. True health occurs not based on a number on the scale. Health is only possible when we believe our body is fundamentally good. We take better care of our bodies when we accept them.2

I love that girls want to look their best, and careful grooming is a form of self-care. Still, I worry that girls put too much emphasis on their looks and embrace too much maintenance (lash lifts, gel nails, lip fillers, and hair extensions, to name a few) as they strive for the “perfect look” at the cost of true self-worth and self-acceptance. When girls feel too fat, too ugly, too awkward, too disgusting, they want to sink inside themselves, turn on themselves, or protect themselves by rebelling against any beauty standard at all. In short, they want to alter themselves and conform. One girl told me she wants to change “all my fat into muscle so I wouldn’t hate looking in the mirror so much.”

Sadly, as girls grow up, and especially as they approach puberty, they learn to hate their appearance. Most body self-criticism takes root between birth and puberty. Although she was born loving herself as is, cultural, societal, and even familial pressures promote negative messaging such as “Be tall, skinny, and this kind of beautiful, with flawless skin and a bright smile.” In other words, “Your body is not good enough as is.” She didn’t choose to internalize this way of thinking or to not love her body, but these messages are prevalent. In fact, we have become so accustomed to believing these directives that we also think self-criticism is necessary and important for self-development. In Come as You Are, Emily Nagoski discusses how women are reluctant to believe they are beautiful and to let go of self-criticism in order to nourish self-confidence and adopt healthy lifestyle habits. She says that body criticism is so entrenched in Western culture that most women hardly notice how ubiquitous and toxic it is. It’s so ingrained, in fact, that “when women start to think concretely about it, they begin to discover a sense that they need their self-criticism in order to stay motivated. We believe it does us good to torture ourselves, at least a little bit.”3 That’s right: self-criticism is seen as both necessary and beneficial.

When I look at girls, I see beauty in many different forms—unique ethnicities, abilities, personalities, and shapes and sizes. I’m sure you see divergent aesthetics in your daughter too. Girls are beautiful, but they are reluctant to believe us when we tell them. There are so many obstacles in her way when it comes to feeling beautiful: her own self-doubt, for example, and unfortunate cultural and societal messages that bombard her with images typically showing one body type and size and a single, narrow definition of physical attractiveness. I’ll give you a hint: it’s not voluptuous and curvy.

Girls learn that the body they have should be scrutinized, must be flawed, and most certainly needs to be altered. They also look outside of themselves for cultural standards around appearance. Kayla, now seventeen years old, told me she didn’t think much about her body until she was older. “I believe it was in Grade 9 when I started comparing my body to my peers and thinking I should be critical, you know, because they were doing it.”

At the same time as your teen is comparing her body to her peers, she’s also sizing herself up against the digitally altered images she sees on her social media feed. She’ll conclude that her body is not only different but wrong. She’ll struggle to find anything that she appreciates about it, and she’ll learn to talk like every other girl around her: “I am so fat!” “I ate way too much last night, so I’m not eating anything today.” Or she’ll ask others, “What do you eat every day? I’d do anything to be thin, like you!” Another girl I spoke with said, “I consciously and subconsciously compare myself to others via pictures and videos of people I see online. This can be for the worse because I will think to myself, They are so fit and healthy. How can I be like them? What do I need to change about myself to become like that?

So what about the girl who does feel beautiful? Who accepts her body? Strangely, she is often viewed as “abnormal,” or even considered a social anomaly. I asked girls what would happen if another girl approached them and declared, “I feel amazing about my body today and love my healthy, glowing skin!” They laughed, thinking I was joking. “This would never happen,” one of them told me. “Never.” Find me a girl who is body confident and you will also find a girl labelled as conceited and “into herself.”

Our competitive and comparative culture puts insane pressure on our girls. Exposure to social media; the obsession with selfies; the power and allure of crafted images that show idealized appearance standards; and myriad products that make empty promises of shinier hair, whiter teeth, and reduced cellulite—taken together, these influences are all too often overwhelming. And they leave teen girls emulating what they see and not what they feel, all the while believing that the perfect body and look can be attained through hard work, sacrifice, and sheer force of will. Girls as young as seven years old complain about frizzy hair, fat legs, and flat chests. I see girls who hide in their hoodies, slouching and turning their bodies inward in an attempt to diminish their developing breasts, and awkwardly carrying around their gangly bodies. One of my clients, Alexis, was mortified by the fact she got so tall, so quickly. Not only did she have to contend with being taller than every boy in her class, but she also had to put up with the constant annoying commentary—“You are so big!” “No kidding,” she’d tell me. What all these girls share is a deep dissatisfaction with their bodies and confusion as to why they don’t feel good. “My body is not enough,” they conclude, “so I’ll change it.” What they long for is unconditional love for themselves. What they experience, whether it is self-imposed or coming from outside influences, is rejection.

Rejection is borne of the self-critical language that so many girls are convinced is the motivator for change (an idea society as a whole has bought into). “If I am harsh on myself,” goes the rationale, “telling myself I am fat, ugly, lazy, and not beautiful enough, I will be driven to change and I will never become complacent or conceited.” It’s the perfect plan to guarantee transformation. Except, in the process, there is no self-love, self-kindness, or self-compassion. A teen girl who pushes herself to lose ten pounds so she feels better about herself may lose the weight, but she may feel awful still, and then confused as to why losing the weight didn’t result in happiness or contentment. This is not the motivation she needs. She may punish herself, perhaps depriving herself of nutrition, exercising in the extreme, or using harsh, self-deprecating criticism. Often, she’ll use the weight scale to measure her self-worth and social currency. Starving for self-love and acceptance, she may wish she were taller, thinner, and more beautiful, with clearer skin, whiter teeth, and curlier hair. Eventually she will disconnect from herself.

I had been working with Naomi for almost a year when she blurted out, “My boobs are too big.” Caught off guard by the randomness of this comment, I asked her to tell me more. Naomi explained that when she was fitted for a new bra the week prior (Mom had vetoed her sports bra preference), the lady helping her figure out the proper size told her she was “small everywhere, except in your bust.” Naomi was mortified. She decided right then and there her boobs were too big and she hated them. She asked me how she could lose weight to shrink her boobs.

I had to tread lightly for a few reasons, as you will have to as well when it comes to growing girls wanting to change their bodies. First, she will be super-sensitive when talking about these issues. Second, her body is still changing, and interrupting the natural process is not advisable. Third, and most importantly, her body is not the problem; the real problem is her perception of her body. What helped Naomi, over the course of our next four sessions, was a shift in focus: from body hating to finding ways to feel good about her whole self.

If your daughter comes to you and expresses a desire to change her body, empathize with her: “This is tough for you and I completely understand.” Then segue from talking about changing her body to changing her habits, and away from losing weight toward gaining a positive relationship with her body. Let her know that there is always something she can do to feel better about herself as she is.

ASHA

A lot of my friends are super-skinny, not that they can control it, but they always say they look anorexic or how they don’t have boobs and butts. This makes me feel so frustrated because I’d kill to have their bodies. I have never tried to change my body, but sometimes I’ll trace imaginary lines on my body and pretend to cut the fat off like a plastic surgeon.

I think I just need to not be so obsessed with what I look like. I probably need more of my own self-confidence and fewer negative thoughts. I probably need less social media too. When you look at any Instagram “model,” you notice how they are all skinny, all muscle, and so beautiful. I think girls compare themselves to other girls and then they obsess over wanting to look like so-and-so. This makes them obsess over what they look like instead of who they are as a person. I probably am the one person who has influenced my relationship with my body—I have a negative influence on my body. My mom always tells me I’m beautiful.

Body Image and the Family Dynamic

Like identity, body image is formed over time and with the feedback of others. For a teen girl, body image can be a positive, accurate, and healthy view. In this scenario, she accepts her shape, size, and body parts, wears clothes that flatter her figure, and feels relaxed and confident as she moves. But body image can also be negative, distorted, and unhealthy. In this scenario, a teen girl is dissatisfied with how she looks and fixated on the body parts she hates. She wears clothes that neither fit nor flatter her unique shape, and looks and feels uncomfortable in her own skin.

While girls worry about how they look, parents worry about how girls feel about their looks. One mom told me, “I think she has a level head on her now, but I worry with middle school that she will start to feel the pressure to look a certain way. I try to keep her focused on what she loves rather than buying into the notion that at this age you have to dress and act a specific way. We worry about her being teased because she doesn’t fit the standard mould.”

Even though cultural and media messages influence your teen girl powerfully, the messages that come from within the family are just as powerful, perhaps more so. I believe parents have an enormous opportunity to positively shape how girls see themselves, despite exponential exposure to media and advertisements. In this section, I want to have a direct conversation with “Mom” and “Dad” about the ways in which you can affect how your teen girl looks at herself through her individual relationship to her body.

Please know that I am using “Mom” and “Dad” loosely here to refer to different types of influence in a teen girl’s life. The roles and responsibilities of parents are shifting from traditional and stereotypical to be much more fluid, expansive, and inclusive. At the same time, though, one parent is often the primary caregiver in the family—meaning their role is more hands-on than a parent who is less involved in the day to day. Here, I will look at the role of each parent separately, with a focus on how teen girls are affected. Regardless of family configuration (single-parent or blended, same-sex or hetero, traditional or non-traditional), your teen daughter benefits from different parenting styles and support. If you think she may need another positive figure in her life, by all means bring one in. You might consider a mentor, a family friend, a member of the neighbourhood, or someone in your faith community. This trusted individual should be someone who can provide her with a different perspective and a different kind of relationship than the one you are cultivating with her. Think of it this way: no one parent (or person) can fulfill all her needs. Thus, a more healthy and balanced approach is to widen her support circle. Add new and interesting people who will see her differently, have varied conversations with her, and have a novel connection to her.

The Mom Effect

Moms often ask me, “How do I teach my daughter to have a positive body image and compete with the unrealistic images she sees daily on her social media feeds and in advertisements?” The answer is to provide ample messages of your own that are healthier and more realistic as you encourage her toward body appreciation.

Start with you: Change begins first with how you speak about your own body and other women. By paying attention to what you do today, you can alter the trajectory of your teen’s relationship with her body for the rest of her life. Complaining that you “look old and tired” or making a comment like “I can’t believe she’s wearing leggings out in public” is damaging. Your daughter hears you, and she will instantly reflect on her own look and clothing choice. Be patient. It may take some time for you to become more aware of your relationship with your body.

If you spend time looking in the mirror and critiquing your body, she will learn to copy you. If you push food around on your plate, pretending to eat, she’ll push her food around too. If you overeat or undereat to deal with uncomfortable feelings like frustration, sadness, or rejection, she’ll add this “coping” tool to her own toolkit. If you limit the types of foods you eat, talk about dieting, or are obsessive with fitness and exercise, guess what? She will follow your lead. By contrast, if you eat a well-balanced diet, focus on fitness, and emphasize feeling good about your body by actively practising self-care, she will learn that this is the path to follow.

Stand strong: I know this is a big ask, especially if you struggle with your own body image, but begin by nurturing her body confidence, which is all about how she stands: tall, head up and chin out, shoulders back, looking strong and poised. At first, this may feel foreign to her, but research on body language and high-power poses by social psychologist Amy Cuddy shows us that how we stand influences body chemistry—lowering cortisol (the stress hormone) and raising testosterone (the dominance hormone). Standing strong can translate into feeling strong. As Cuddy explains, standing like a superhero for only two minutes can create the belief that “I can do anything” and empower girls to feel assertive and brave enough to take risks. “Fake it ’til you become it.”4 Stand with her; practise together. Feel good about your bodies together.

Focus on feeling over appearance: It is all too easy to gain quick connection with our girls by complimenting their appearance: “I love your outfit,” or “You look so pretty today.” Well-intentioned, yes, but when we highlight the superficial, she comes to believe that this is her true value. In other words, she internalizes the idea that what she looks like matters most, and she may feel our attention and love are contingent on her appearance. Let’s use our words wisely, commenting on her attitude, her work ethic, and the dreams she wants to create and step into. Instead of complimenting her physical beauty, try complimenting her competence: “I see how hard you have been working today,” or “You’re really showing focus and determination when you practise.” Phrases like these help her embody her core qualities and prioritize her power over her prettiness. When she asks you, “How do I look?” you can answer, but don’t leave it there. Ask her, “How do you feel?” Remind her to focus on personalities and not attire when she is with her friends, and let her know that she can influence her peer group with her meaningful compliments in place of the social norm of criticism.

Shatter the mirror: Girls can become trapped in the mirror, endlessly fussing. Let them know that although we do not want them to leave the house with clothes mismatched or makeup running under their eyes, they need not spend too much time glaring at their reflections and looking for body parts they feel are imperfect or need “shaming.” When she looks in the mirror, help her to focus on the body parts she loves and use positive messaging when speaking about herself: “My legs are so toned and strong,” for example, or “I love the colour of my hair.” Encourage her to shift her focus from the mirror to real life, where there is so much more to think about than just body image—creating arts and crafts, photography, playing sports, skateboarding at the skate park, or meeting up with friends. Teach her to care less about looking good and more about truly living.

Dr. Marissa Bentham—clinic owner, chiropractor, and mom—is aware of her impact on her daughter’s self-image. She offers this insight: “I’ve maintained a strong awareness that my daughter is always watching and listening to me when I get dressed, when I do my hair and makeup, and when I look at myself in the mirror, so I am very intentional about the messages I send her. I am very careful not to criticize myself or my body, both for my own healthy body image, and for hers. I do put time, care, and attention into my appearance and sometimes I am concerned that it may be influencing my daughter to put too much focus in this area. I try to always reiterate to her that who we are is so much more important than how we look, but that it’s okay to want to look and feel our best.” Dr. Bentham makes a great point: a healthy body image can include both looking and feeling good; it doesn’t have to be one or the other but a balance of both.

Choose connection over disconnection: Girls turn against themselves when something goes wrong, whether that something is a poor grade, a fight with a friend, or simply not feeling good enough. They can choose to suffer in silence and disconnect not only from us but also from themselves. Unfortunately, their bodies are easy and accessible targets for their sadness, frustration, and even anger. As she becomes hyper-focused on her body—and buys into the logic of “if I were prettier, skinnier, or sexier, then I’ll feel happier”—she can easily disconnect by ignoring her feelings and often negating physical signs such as hunger, thirst, or fatigue. Worse yet, she can punish herself by overdoing it with eating, sleeping, and exercising, or distract herself from discomfort with social media and screen time. As she disconnects, she can feel more lost than ever.

This is where moms have an important role to play: you can remind her how to connect. She may not want to talk to you and connect through conversation, but you can gently point out that she may need to amp up her self-care regime. Make suggestions: drinking enough water; taking time to prepare and then nourish her body with a wholesome meal; moving her body and doing something she loves to do (preferably outside); getting enough sleep (despite the changes in her circadian rhythm that will make her want to stay up late);5 taking time to process her feelings by journalling or speaking with you. Remind her that whatever she is going through is just a moment, and that moments have a beginning and, yes, an end.

The Dad Effect

Throughout my years of working with young girls and their parents, I have seen a drastic and impressive shift from dad disengagement to dad involvement, especially when it comes to body image. In the early years of my practice, dads often appeared awkward and uncomfortable around their teenage daughters with their changing bodies, changing hormones, and emergent and strong opinions. I would hear their oft-repeated refrain, “I leave those conversations [about puberty] to her mom.” Now I field questions from interested dads who want to know, “How can I connect with her? How can I support her, and what do you think she needs to hear from me?”

Dads worry about their daughters—about their self-confidence, clothing choices, attention-seeking behaviours, and sometimes-provocative social media feeds. They may feel frustrated by the emergent conflict between her and her mom. Most dads want to be involved in their daughter’s life, and they seek to establish a healthy, loving, and fulfilling relationship. However, they often don’t understand why their daughters may radically fluctuate from bright and bubbly to angry and explosive. They wonder what happened to their sweet little girl, who has seemingly and spontaneously been replaced with a door-slamming teenager. They want to help but they don’t know how. Here are some ways to move past that bewilderment.