Читать книгу Rooted, Resilient, and Ready - Lindsay Sealey - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

IT’S 5 A.M. and I am sitting at my local coffee shop. Nobody is here yet and I am relishing the quiet. My pencils are sharpened, my brightly coloured Crayola felts are fanned out around me, and I am opened to a fresh, blank page in my notebook. I am a little afraid, a little nervous, but mostly, I feel excited and energized to begin writing this book. I am ready—ready to ask questions, to delve into tough topics, to learn and grow, and to empower you to be ready for the teen years as well. I am ready to be real and raw, ready to work hard and keep focused, and ready to inspire change. Even still, I have a problem.

I have so much to say when it comes to growing our teenage girls that I don’t know where to begin. Maybe you feel this way too sometimes: you want to support your daughter so much but you don’t know where to start. Don’t you just wish you could ask Alexa, or maybe Siri: “How do I help my teenage daughter?”

Suddenly, I become aware of three questions swirling through my mind like a merry-go-round: What do I wonder about young girls? What do I worry about when it comes to teen girls? And what do I wish for every girl? This is where I will begin.

I wonder all the time about teenage girls today. I wonder how they are feeling and what they avoid feeling. I wonder what they are thinking about and what they have yet to consider. I wonder if they have learned that it’s okay to be themselves—whether that means being focused and serious, silly or a little crazy, spontaneous or predictable, boisterous or demure, adventurous or safe. I wonder how they are navigating the newness of the teen years and all the changes this stage of life brings. I wonder who they are becoming and how they are being influenced and shaped. I wonder how they see our world. I wonder if they feel they belong in this world.

At the same time, I worry about today’s girls. I worry about how quickly they are growing up, and the pressure I know they feel to be “perfect.” I worry about their busy schedules, their push for more, and the stress they are forced to deal with every day—to keep up, to fit in, to look like they know what they are doing, to achieve, and to succeed. I worry about the pressures they feel specifically when it comes to relationships, sex, and social media. I worry they are becoming who others want them to be rather than investing the time needed to figure out who they want to be.

I also spend a lot of time wishing. I wish adolescent girls could see what we see. I wish they could see their potential for power, strength, and confidence. I wish for them to grow up strong, with self-belief, dogged determination, and the ability to work hard—with grit, perseverance, and unwavering resilience. I wish that every single teenage girl could love and value herself, do all that she loves to do, know her greatness, see her beauty, feel confident, take risks, show her boldness and audacity, voice her opinion, and absolutely not care what people think. Ultimately, I wish for teen girls to feel rooted, resilient, and ready for this world—for both what it has to offer them and for all they have to contribute.

That’s why I wrote this book—to help you guide her to be rooted in her identity, resilient to the changes and challenges she will face as she grows up, and ready to become her best self as she steps into her future. One parent I spoke to said it best: “We want our girls to be strong, happy, and healthy, filled with love and hope, and purpose.” Yes, we do. The question is “How?” I hear often from parents with variations on this simple question. “How do we nurture relationships with our teen girls when they push us away?” “How do we get close when we feel so far removed?” “How do we understand what they are going through when they don’t tell us any details?” “How do we support teen girls as they grow up, guiding them in the right direction while also giving them the space they want and need to make their own mistakes and figure things out for themselves?” I know you wonder and worry too. And I want to address your concerns, offer suggestions, and answer those questions.

The things that I wonder about, worry about, and wish for girls have changed and intensified as the world has advanced rapidly. Twenty years ago, the world was a different place. Over a decade ago we didn’t have smartphones, Facebook, Instagram, or Snapchat. We shopped in real stores, not virtual ones. We had in-person conversations and caught up over coffee. We may be getting used to this version of living—this is all girls know to be true—but there’s no doubt that many of these recent changes have increased the pressure for teen girls to grow up. There is pressure to be beautiful and talented, equipped and empowered, and involved in the community. There is pressure to keep up with social media and trends, fit in with friends (while also discovering her uniqueness), and make it all look effortless.

Girls today are part of the iGeneration, a cohort born between 1995 and 2012. They are known to be super-comfortable with technology and constantly “connected” to social media and their devices.1 This is how they relate to one another, how they survive; in fact, it is the only way they know. They prefer software to hardware (an e-book or audio version as opposed to an actual book), and they live in a fast-paced, always changing, digital world, with access to anything they want 24/7. Occasionally, they will step out of their online world (BRB, or “be right back”) to spend brief moments in the real world—perhaps for a breath of fresh air or a snack—before heading back to the familiarity and comfort of the internet. She will typically be wearing jeans, a topknot, and ear buds, and she’s likely involved in several “textlationships” (a relationship primarily based on texting).

There’s no doubt that this ubiquitous digital world shapes and influences a girl, exposing her to thousands of digital images as she scrolls and swipes her device for up to nine hours each day.2 I am convinced that this constant stream of info and imagery is having a profound impact on the pressure she feels to be all things to all people. Research3 shows that this generation of girls is growing up sooner and faster than any other generation, physically, emotionally, socially, and, yes, sexually.4 There is the pressure to be herself but also to conform; to have a voice but refrain from being too loud or too strong; to be a leader but not overly ambitious or threatening; to do her part in the home while creating her own life outside of its comforts; to think for herself but to ask for help when she needs it; to maintain her social media profile yet withstand the pressures to be pretty and sexy; to focus on being her best self without joining the chase for perfection. These are the pressures girls talk openly about.

Less often mentioned, but arguably applying even more pressure, are the silent struggles teen girls often hide: struggles with gender identity, sex and sexualization, and mental health concerns such as anxiety and depression. And then there is the brewing conflict between yearning for independence and feeling stuck in a state of dependence, between wanting to face the world alone and prepared, and knowing (but perhaps not admitting) that she’s just not ready—yet.

Your teenage daughter is changing in every way imaginable. Her body is changing as she goes through puberty. Her brain is changing as it sprouts, prunes, and reorganizes neuronal circuits.5 Her language is shifting to become more self-deprecating and comparative. And her social circles are evolving as she tries to figure out who she is and where she belongs. These are the years when her inner circle of friends becomes so important. Not only do they benefit from her time and attention, but they also become the holders of her secrets, the ones she trusts with the inner workings of her mind. It is a time of great change for you as well, as you must learn to let go of her hand and let her grow up.

Imagine a circle. When your daughter was a little girl, the two of you stood together in that circle. Now that she is a teen, she is standing in the circle on her own. Using a hula hoop as a prop, I tell girls: “You are the centre of your own circle. Two feet planted firmly on the ground. You are the one who gets to make your own choices and decisions and decide who and what you want in or out of your circle.” Her circle is her boundary; her circle is her power; her circle is the life she is creating for herself. And it truly is her circle. You are no longer in the centre with her, and this is a healthy indicator of her growth.

Although you are her chef, chauffeur, cheerleader, tutor, coach, counsellor, and—let’s face it—bank machine, you are no longer her everything. But you are her someone. As she grows, you experience the tacit process of letting go of who she once was and watching her grow into someone new. This can be difficult. At the same time, though, it is incredibly rewarding. As teens grow, they are yearning for independence, freedom, and the chance to show you that they can do it, that they don’t need you quite as much as they used to. The hand that reaches out to hold yours every once in a while is just as likely to be raised in the classic gesture that says “stop.” It’s her way of telling you, “I got this. I don’t need your help!”

Parenting from the Periphery

Popular culture has some stereotypical boxes for parents, including tiger parents (strict and demanding parents who push and pressure their children); helicopter parents (who pay extremely close attention to their child’s experiences and problems); lawnmower or snowplow parents (who attempt to save their children from any obstacle, pain, or inconvenience they may face); outsourcers (parents who choose to pay professionals to do the work of parenting for them); and jellyfish parents (who let their kids do anything they want).6 In The Dolphin Way, Dr. Shimi Kang suggests that the ideal parent is authoritative in nature but firm and flexible.7

The parenting style that is best for you and your daughter will depend on your unique relationship. Sometimes parenting will require tough love: reinforcing the rules you have set out for her when she needs to be held accountable for her actions (or inactions), or when she has to be called out on rudeness, disrespect, and disobedience. Other times, you’ll need to offer her soft love: when she is being hard on herself, when she has royally screwed up and she knows it, or when she is going through hardships or a season of loss. You know best how she ticks, and what is needed depending on the situation at hand.

The style of parenting I recommend is that of the periphery parent. You are not her friend or in her circle. You are her parent—far enough away so she has the space and freedom to make her own choices, to feel free to be herself, and, yes, to make her own mistakes, but close enough to offer your encouragement and guidance and provide strength and security as she needs. She will show you she is ready to be her own person, but remember this: she still needs you, just in new and different ways.

Parenting from the periphery requires a new way of relating and a new approach. Periphery parenting means getting comfortable with being the observer on the outskirts, the silent supporter, ready when she needs you or when absolutely necessary but avoiding interfering or intervening when she is doing all right on her own. As we all know, teen girls can be moody, unpredictable, rebellious, truculent, and confusing. But they can also be strong, brave, confident, courageous, loving, enthusiastic, surprising, and amazing. This is why how we speak to them and also about them matters so much, as does how we treat them. Treading carefully and intentionally through these unchartered waters is not easy (we may fall into power struggles, arguments, and use of “colourful language”). Nevertheless, I encourage you to keep at it with patience and practice, to acquire some knowledge of the development of the teenage brain, and to accept that from time to time you will make mistakes too. Because that is what she wants from you!

Begin parenting on the periphery with listening: listen to what your teen girl has to say, and feel for the emotions behind her words. Listen without judgment. Wait in the silence and allow her to pause and consider before speaking. Hold space for her to simply be in the moment or in the feeling with you. Let your daughter make choices and help her predict the consequences. Choose truth-telling without sugar-coating or lies. Carefully monitor her emotions and decide when a situation is serious enough to get involved. Be ready to talk and “lean in” when she signals that she is open for it, and be willing to back away and commit to trying again another day when you feel her shut down. Opt for asking open questions such as “Can you tell me more about your weekend?” instead of “Did you have fun?” Let her speak and don’t rush to change topics, especially if you feel uncomfortable. Give advice if it is warranted, but ask her if she wants it first. Choose guidelines over rules and, where possible, create these together.

On days when you feel you are screwing up—such as when you make assumptions about her, lose your patience, pick a fight, correct her, take over to show her how it’s done, or jump in to solve her problem—accept that you are not perfect, and neither is your daughter. What you can be is an “eternal learner,” a parent committed to learning every day and never giving up.

So much can get in your way when you parent your teen girl. You may feel you are inadequate, archaic, or irrelevant (teen girls are adept at making you feel this way!). You may be consumed or overwhelmed with your own history or past mistakes. Your daughter needs you to let go of and move through those feelings so you can keep providing her with a safe space to be her true self, to unburden, and to lean on you. This will take self-belief and confidence, time, effort, and so much patience on your part. And then, just when you figure it out, she will change and need you in a new way. This is precisely what makes parenting both interesting (and surprising) and unending.

Connecting with Your Teen

Your connection with your teen girl, and how you connect with her, is everything. As a parent on the periphery you’ll be challenged to cultivate connection in new and possibly creative ways. Research in the 1960s and 1970s conducted by attachment theorists such as John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth8 and the most recent neuroscientific studies support the concept that there is great power and vitality in relational connection. Attachment is the innate biological mechanism that bonds humans together and underlies love. When you create a safe and trusting relationship with time, presence, understanding, and emotional attunement, your teen learns she can rely on you. She feels seen, heard, validated, and valued; she feels that you “get” her. This kind of connection—whether with you or someone else who is close to her—helps a girl feel secure and calm.

When you connect in any way with your teen girl, you contribute to her brain’s neural connectivity and its physical structure. Neuropsychologist Donald Hebb coined the phrase “neurons that fire together, wire together” to describe the process of neurons in her brain firing with each experience. Over time and with repetition, this firing creates stronger and faster neural connections, particularly in the limbic system, where the attachment circuitry lies and where her emotions are regulated.

The “right” kind of connection transpires when her experiences are met with kindness, empathy, and reassurance: words, for example, such as “I am here for you” or “I understand how you are feeling.” This stands in contrast to the connections that are forged out of criticism and judgment or shame and blame. These negative connections activate a girl’s stress response system. They alert her to danger by flooding her body with adrenaline and cortisol (the stress hormones) and propelling her into the automatic “flight, fight, and freeze” mode. They also wire her brain’s circuitry to be hyper-aware for and anxious about the next instance of perceived danger. She will flounder and feel uprooted.

If you are feeling concerned because your daughter has already experienced anxiety-provoking situations or trauma, please hear this: There is hope. The plasticity of the brain allows for change. Wherever she is at and whatever she has experienced, her brain has the capacity to create new neural pathways. You can help to rewire her brain by exposing her to new experiences and connecting with her via empathy, compassion, and care, all of which allow her to feel safe and cared for, decrease her stress levels, and increase feelings of security. In order to feel competent, teen girls need one relationship that engages heart and mind. This relationship may be with you as her parent, or another adult with whom she can be herself and share and feel safe.

Researchers and scientists work hard at proposing hypotheses, experimenting, and reporting their findings. We glean the benefits of such diligence. But beyond all of the research, and beyond all of the things that you instinctively know, is one vital thing: love. Despite the teen rebellion, despite the eye rolling, the hand-on-hip mannerisms, and the sarcastic wit she has now mastered, you love your teen daughter unconditionally, relentlessly, fervently, deeply, and unequivocally. You love her because that is the most important thing you have to offer her as her parent. Your love promotes connection.

Disconnection happens when your daughter feels unable to speak freely. She may feel blocked by fear of being judged, criticized, or misunderstood, and she will hold back and hang on to the accompanying frustration of her missed opportunity to disclose. Disconnection sounds like “Really? You decided to wear that today?” or “Are you still working on your homework? What’s taking so long?” We disconnect from teens any time we judge, criticize, assume, and throw doubt or disbelief their way; when we tell them how they are feeling, give advice too readily, or try to fix or solve problems without involving them. Disconnection is not what you or your teen girl wants, but it can happen in the blink of an eye, and afterward, you may catch yourself wondering why you said what you said or did what you did. No one is immune. This happens often with my teen clients, especially when I say the wrong thing, make the wrong suggestion, or forget something she has told me countless times. The imaginary brick wall comes down—she will not say a thing—and I am stonewalled. But these moments of disconnect can be remedied if you work to become aware of when they are happening and seek to turn that around. I wrote this book to help you do just that.

The insights in these pages are based on my experience with teen girls and those supporting them. I have gained a plethora of ideas from girls who have told me what helps their growth, and what hinders it. I’ve also learned from their parents, who have expressed their concerns and let me know where they have most succeeded. Rooted, Resilient, and Ready is designed to help you parent your “becoming” teen daughter in this changing world. It offers an exploration of the eight most important concerns when it comes to raising teenage girls today: identity, body image, mental health, social media, relationships, peer pressure, sex, and the future. Throughout, I will offer my own revelations about teen girls and the practical tools I have tried; what parents are experiencing with their daughters; and what girls themselves have to say. Each chapter includes conversation starters, and ends with concrete steps you can take to help her growth, along with a list of corresponding countersteps that can hinder it. For printable PDFs of key concepts, visit www.LindsaySealey.com. There is also a resource section at the end of this book with recommended websites, apps, and TED Talks.

Teenage girls have always interested and fascinated me as much as they have baffled and bewildered me. At times, girls offer viewpoints that I find so refreshing and creative. Other times, I too experience the brick wall—the one constructed to keep us out and block us from reaching her. Like you, I sometimes don’t know how to get in. What I do know is that I never give up. I keep trying and, eventually, I find my way. I am asking you to do the same. Some days, I celebrate my triumphs (even the small ones, like getting her to smile). Other days I wallow in my failings (I know I came across as critical and harsh). What works one day may not work the next. What works with one girl might never work with another. We all have to remember that we are doing our best, and as life changes and she changes, we can change too. And please be assured that not all of the changes I discuss in this book are going to happen all at once!

You decide what works best for you and your daughter—there is no perfect blueprint. You will have to find your own way as well. Take one step and one day at a time. As she establishes her circle and feels your support from the periphery, she is likely to invite you in—but in her time and her way. If we want girls to step into the best version of themselves, we need to step out of their way while we continue to reassure them that we’ll be there for them. Step by step, we can help girls be more rooted, resilient, and ready for whatever their future may bring.

NOTE TO READERS ON INCLUSION

Rooted, Resilient, and Ready has been written to nurture and support those raising teenage girls. Its aim is to provide the necessary and relevant research, information, experiences, and ideas and, at the same time, be as inclusive, expansive, and collaborative as possible.

With this goal comes the consideration of a diversity of teenage girls with respect to size, shape, and body type; ages and abilities; family, cultural, ethnic, and religious backgrounds; levels of education, social economic status, and external influencing factors; psychological dispositions, personality types, and maturity levels. Some content will be more relevant for your thirteen-year-old; other content will be more suitable for your seventeen-year-old.

That said, Rooted, Resilient, and Ready has its limitations. First, there is the limit of the author’s worldview. How we make sense of the world is shaped by personal life experiences, cognitive capacity, and perceptions and interpretations. Even with an open mind and good intentions, one can not consider all possibilities or all perspectives. This is also true when considering different beliefs and value systems. Different parents will have different “hard lines” when it comes to various topics, especially with relationships, substance use, and sex.

Second, Rooted, Resilient, and Ready seeks to proffer advice and guidance to readers. But a book can never replace professional medical attention. Those with serious concerns need customized advice from the most appropriate experts. If you feel that a young person is in danger or is endangering someone else, please take immediate action and seek professional assistance.

Third, this book is bound to the societal constructs of gender and non-traditional gender identities. For constancy, the pronouns “she” and “her” are used throughout, even when individuals have identified as non-binary. However, it is the hope that as societal changes are further embraced and accepted, the language will become more inclusive and new language will emerge.

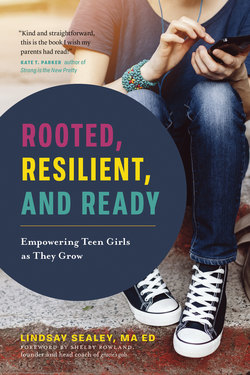

Finally, the true stories and experiences of girls and their supporters are presented. To protect the privacy of individuals and their families, names and identifying details have been changed and thus individual stories have become compilation stories. This is with the exception of the photos throughout the book, where the girls have permitted the use of their real names.