Читать книгу AMERICAN JUSTICE ON TRIAL - Lise Pearlman - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеYou can jail a Revolutionary, but you can’t jail the Revolution.

You can kill the Revolutionary, but you can’t kill the Revolution.

— FRED HAMPTON

(CHICAGO CHAIRMAN, BLACK PANTHER PARTY, 1969)

American Justice on Trial revisits in light of current events People of California v. Huey P. Newton — the internationally-watched 1968 murder case that put a black militant on trial for his life for the death of a white policeman accused of abuse. The trial put our nation’s justice system to the test and created the model for diversifying juries “of one’s peers” that many of us now take for granted as a constitutional guarantee. In the process, protesters orchestrated by the defense generated a media frenzy that launched the Black Panther Party as an international phenomenon. Using this trial as their platform, the Panthers took aim at entrenched racism in a democracy founded on the principle of equality. They put their sights on toppling white male monopoly power, and they convinced many followers to pay it forward. They also prompted an extraordinary backlash from those in power. The ramifications of this decades-old conflict continue to unfold today.

The year 2016 marks a half century since Huey Newton and Bobby Seale founded, in Oakland, California, a small militant group that they named the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. Like Black Lives Matter, Black Youth Project and other civil rights activist groups today, Panther members were predominantly in their late teens or early 20s when they took to the streets, challenging the nation’s criminal justice system and making bold accusations of abusive policing. Today almost everyone recognizes the image of Black Panthers in iconic black leather jackets and berets, their fists raised in defiant salutes. In 1967, that fledgling organization would likely have disappeared quickly if not for one riveting murder trial. Now — a half century later — is an especially good time to take a fresh look back, to reexamine what may very well be the most pivotal criminal trial of the 20th century and ponder what it tells us about the importance of diversity, if we want to improve some of the most glaring shortcomings in our beleaguered American justice system.

2016 began with intense populist attacks on the federal government from both the Left and the Right. Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump promoted a nationalist agenda that promised to “take America back” to an idealized earlier conservative era of white Christian domination, while disenchanted youth rallied in response to a call for political revolution against economic inequality by Bernie Sanders, a Democratic Socialist who came of age in the turbulent 1960s.

2016 also began with an armed takeover of a federal wildlife refuge in Oregon by a small contingent of militant white ranchers who sought to instigate a broader revolt against the United States government. The response of the FBI says a great deal about race relations today. Back in 1993, federal agents engaged in a deadly gun battle with white religious cult members in Waco, Texas, when the agents were denied access to a private compound to search for a stockpile of illegal weapons. A 51-day siege ended in the fiery deaths of 76 more people, including women and children inside the Branch Davidian compound, amid widespread public criticism of the Department of Justice’s handling of the confrontation.

On the second anniversary of the Waco siege, white army veteran Timothy McVeigh and co-conspirators took revenge through the devastating bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building — the deadliest act of domestic terrorism our nation has ever experienced. The explosion killed 168 people, injured many more and caused extensive damage to hundreds of nearby structures. The unprecedented bombing at first sparked fears across the country that it was the act of Arab terrorists. The FBI embarked on a nationwide manhunt, and after collecting tons of documentary evidence and conducting 28,000 interviews, found the death and destruction to be the work of homegrown bombers. They arrested McVeigh and Terry McNichols, another member of the same rightwing survivalist group; a third man turned state’s evidence for a reduced sentence. University of Missouri constitutional law professor Douglas Linder maintains a website dedicated to famous American trials. He is among experts who assert that the closure of the Oklahoma Bombing case left many questions unanswered, including why the government failed to prosecute anyone else “despite considerable evidence linking various militant white supremacists to the tragedy.”1 Indeed, white supremacists celebrate McVeigh as a martyr to the cause of a rightwing overthrow of the federal government.2

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) tracks domestic terrorism. It has noted a sharp rise in terrorist incidents since Barack Obama became President. In 2009, the heads of the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security told Congress they considered homegrown terrorists as much of a threat as foreign terrorists. By the end of 2015, the monitoring of hate-mongering internet networks by the SPLC revealed a significant uptick — its annual Spring Intelligence Report characterized 2015 as “a year awash in deadly extremist violence and hateful rhetoric from mainstream politicians.”3

In January 2016, federal agents took a careful and measured approach to the Oregon armed takeover of public land. Unlike the siege at Waco, the Oregon siege ended after 41 days with only one death and the surrender of the other white militants, who then faced criminal charges. What repercussions would there have been if the Oregon takeover of public lands had instead been perpetrated by a small band of Arab jihadists or by black militants? Journalists immediately speculated that racism played a major role in political reaction to the Oregon standoff.4 Many Americans would never have expected, or tolerated, a similar restrained FBI response if the militants were not white.5 Reaching back half a century to compare the illegal armed seizure of public lands in Oregon to an infamous Black Panther protest in Sacramento in 1967, one commentator wrote:

[Unlike] what’s happening in Oregon right now, [the Black Panthers] entered the state Capitol lawfully, lodged their complaints against a piece of racially motivated legislation and then left without incident. But for those who see racial double standards at play in Oregon, the scope and severity of the 1967 response — the way the Panthers’ demonstration brought about panicked headlines, a prolonged FBI sabotage effort and support for gun control from the NRA, of all groups — will serve as confirmation that race shapes the way the country reacts to protest.6

Young people today may find it hard to believe that the nation was in fact more polarized over race in the 1960s than it is now. What has changed in race relations since that tumultuous era? What hasn’t? Consider the radically differing reactions to the 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the 2016 Super Bowl halftime show. In October 1968 African-American Olympic track medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos shocked observers around the globe with an emphatic civil rights gesture during their awards ceremony — each raising a black-gloved fist in a classic “Power to the People” salute. They were promptly banned from the Olympics for life.7

In 2016, during halftime at Super Bowl 50, more than 110 million viewers witnessed megastar Beyoncé’s dance troupe perform a similar raised-fist tribute to the Black Panthers, whose own fiftieth anniversary year coincided with that of the Super Bowl. Just a day earlier Beyoncé released a new video, “Formation,” which paid homage to the Black Lives Matter movement. Beyoncé’s polarizing halftime message triggered a barrage of negative tweets and blogs as well as calls from conservative politicians, talk show hosts and police to boycott her performances, all of them unlikely to diminish the entertainer’s enormous fan base.8

The Super Bowl incident is just one illustration of hot-button race issues that have recently dominated the airwaves. In the last few years — unlike prior eras in American history — deaths of unarmed blacks at the hands of police have garnered as much news coverage as killings of officers. Technology advances are the primary reason race issues today take place in a particularly volatile context: the near-constant presence of smart phone cameras has turned millions of Americans into potential on-the-spot documentarians.

In 2013 director Ryan Coogler made the acclaimed film Fruitvale Station about the last 24 hours of the life of Oscar Grant III, which ended violently on New Year’s Day 2009. Cell phone videos captured a white Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) police officer shooting Grant while he was handcuffed and lying face down on the platform of an Oakland BART station. Like the onlooker’s video seventeen years before of Los Angeles police viciously clubbing black cab driver Rodney King after King was stopped for speeding, the clip of officer Johannes Mehserle killing Grant was replayed over and over to a shocked public. The outraged reaction to Grant’s death was immediate. Although the rioting and looting in downtown Oakland never came close to the scale and impact of the devastation following the acquittal of white policemen who had thrashed Rodney King, vandals in 2010 caused extensive damage to hundreds of Oakland businesses and parked cars. Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale, then in his early seventies, was among those who spoke out to restrain the senseless violence.

Mehserle claimed he only meant to use his Taser, but the Alameda County District Attorney concluded that Mehserle’s behavior was reckless and charged him with murder — making him the first California law enforcement officer to face such accusations in decades. Mehserle’s lawyer won a change of venue to Los Angeles after an opinion poll showed a sharp racial divide between whites and blacks in Alameda County over the presumption of Mehserle’s guilt and the likelihood of violence if he were to be acquitted. In 2010, a Southern California jury with no black members convicted Mehserle only of involuntary manslaughter; he served less than two years for that crime.

On March 21, 2009, Oakland again made grim national headlines when two policemen stopped an ex-felon in broad daylight for a routine traffic violation in a crime-ridden section of East Oakland’s flatlands. Lovelle Mixon was armed with a semi-automatic hand gun and an AK-47. Desperate to avoid returning to prison for parole violations, the 26-year-old Mixon opened fire on the surprised motorcycle cops and fled the scene. Cornered soon afterward, Mixon killed two members of a SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) team before being gunned down himself. It set a chilling record — the worst single day of police fatalities in the violence-plagued city’s history, adding an ironic and bitter coda to a year in which the number of police officers killed nationwide by gunfire in the line of duty had reached a fifty-year low.9

President Obama sent his and his wife Michelle’s somber thoughts and prayers to the policemen’s families and the community, expressing the nation’s gratitude “for the men and women in law enforcement who . . . risk their lives each day on our behalf” and condemning “the senseless violence that claimed so many of them.”10 Three days after the shootings, Oakland’s then mayor, former Congressman Ron Dellums, expressed the city’s grief at an evening vigil. Many police officers still despised Dellums for identifying with the Panthers as a young Berkeley politician in the ’60s and early ’70s when the Panthers were at war with the police. In that earlier time, in February 1968, Dellums had stood on the Oakland Auditorium stage in solidarity with revolutionary black leaders who pledged vengeance if Huey Newton were executed for killing Oakland Police Officer John Frey.

In 2009, a much more somber and reflective Mayor Dellums expressed the city’s “shock and sadness” at officers who paid the ultimate price in service to community: “We come to thank them. We come here to mourn them. We come here to embrace them as community.”11 In the view of law enforcement, Officer Frey’s death was in the same category as the four officers killed in 2009 — men who heroically gave their lives for public protection. The names of the four officers killed by Mixon and their date of death have since been chiseled into the memorial at Oakland Police headquarters where John Frey’s name also appears among other Oakland officers killed in the line of duty since the city’s founding. Every year local officials join members of the department and surviving family of the officers in a formal ceremony to honor their sacrifice.

Such tributes to fallen officers reflect enormous societal appreciation for their dedication to public protection, as we saw again with the outpouring of support for the five Dallas officers murdered on July 7, 2016, and their wounded colleagues — the most casualties for law enforcement in a single incident since September 11, 2001. Before he died, sniper Micah Johnson claimed he targeted policemen on duty at the Dallas protest in retaliation for deaths elsewhere of black arrestees.

The shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014 triggered renewed attention to allegations of abusive police conduct, intensified by more recent deaths of unarmed arrestees elsewhere across country. Months later a passerby’s cell phone in North Charleston, South Carolina, shocked Americans with footage of a policeman shooting African-American Walter Scott in the back as Scott started to run away following a routine traffic stop. The officer has been charged with murder. That same month in Baltimore, a cell phone caught police handcuffing Freddie Gray. When the 25-year-old African-American died of injuries after bouncing around the back of the police van en route to being booked, the incident sparked the worst riots in that city in almost five decades.

Unlike the police force in Ferguson, the officers in Baltimore were racially diverse and operated under a black police chief and mayor. The dysfunction in Baltimore has been traced all the way back to riots in 1967 and 1968 from which the impoverished city never recovered.12 Baltimore still lacks resources for sufficient beat cops and suffers from high crime, drug addiction, joblessness, underfunded schools and urban blight. While Baltimore quickly replaced its police chief and undertook a new approach to police training, the Ferguson city council only agreed to sweeping reforms proposed by the Department of Justice when threatened with a civil rights suit in federal court. Federal District Judge Catherine Perry approved the Ferguson settlement “in everyone’s best interest and . . . in the interest of justice.” The mayor of Ferguson promised swift progress under the agreement as “an important step in bringing this community together and moving us forward.”13 The settlement agreement requires police officers to undergo diversity training, to track arrest records and use of force, to wear body cams and to be monitored for compliance on an ongoing basis. In other cities across the country, accusations of racist policing are also moving from protests in the streets to resolution in court.

Ultimately, the Department of Justice reinvestigation of Michael Brown’s death agreed with the Ferguson Grand Jury’s decision not to indict the officer who killed him. All charges against the six Baltimore peace officers who faced prosecution for Freddie Gray’s death were also dismissed, but the mayor requested a Justice Department review that resulted in a highly critical report documenting systemic racism. Major reforms have been promised. Investigations into several other highly publicized incidents are ongoing. Inflammatory clips widely circulated at the outset may or may not reflect the whole picture that emerges on thorough investigation.

How will this play out? Chance footage filmed by passersby feeds suspicion that widespread mistreatment of minority suspects would be revealed if only there were more transparency. Unlike officers’ deaths, fatalities caused by the police have not systematically been tracked over the years. Going forward, that is already beginning to change. As we consider proposed solutions to the current divide between police and minority communities, what can we learn from how media-savvy activists drew an international audience to a murder trial that turned the tables and put the American justice system itself on trial nearly a half century ago? And how did it all start?

West Oakland was a tinderbox long before the Black Panther Party came into being — a ghetto suffering from two decades of high unemployment, overcrowded housing and heavy-handed policing. The black community considered patrolmen an occupying army. In their view, whenever a crime was committed, the police seemed too eager to blame it on a black man. Although “shoot to kill” was not official policy of the Oakland Police Department (“OPD”), in practice patrolmen could kill fleeing burglary suspects with impunity. Black and other minority residents feared officers imposing their own death penalty on the streets with no trial, no judge and no jury. Even in the courts a “jury of one’s peers” for black defendants still too often resembled the 12 Angry [white] Men in the 1957 classic Henry Fonda film.

By the late 1960s, the Vietnam War had created yet another societal fault line in America, splitting the country between war hawks and doves. The division fell largely along generational lines, with college students among the most vociferous opponents of the war. Eighteen-year-olds could be drafted and killed in war, but could not vote. “Never trust anyone over 30” became a popular slogan. The tense political situation in Oakland mirrored the nation as a whole. Older white men maintained a lock on the power structure, including the courts. The established press remained almost exclusively white male. Black and Latino youths disproportionately faced shipment overseas for an unpopular war from which they might easily come home disabled or in coffins.

In the midst of increasing unrest, in October 1966 Huey Newton and Bobby Seale launched the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense with a 10-point program that included demands for decent jobs, education and housing, exemption from the draft, trial for those accused of crimes by a jury of true peers, and an end to police brutality. Huey Newton welcomed to the Panther Party other street toughs who, like him, had criminal records and a reckless streak. Despite sympathy among liberals for many of the Panthers’ demands, the Panthers’ hostile rhetoric and ostentatious display of guns alienated and threatened far more Americans than they attracted to their cause. Older residents of Oakland’s flatlands found the Panthers too confrontational. The Panthers scared them with their open display of weapons. Even sympathizers worried the Panthers would precipitate nothing but their own deaths at the hands of the police. Yet many young blacks welcomed the brashness of the Panther Party and wholeheartedly embraced its call for armed self-defense.

In August 1965 devastating riots had raged for days in the Watts area of Los Angeles. In their aftermath, the anxious Johnson administration sent experts from Washington to tour ghettos across the country. They concluded that Oakland was “one of the most likely to be the next Watts.”14 “Some believe[d] . . . any incident [could] spark an explosion.”15 Oakland surprised observers by remaining quiet during the long, hot summer of 1967, even while race riots erupted in Detroit, Newark and other cities across the country. Following those riots, FBI Chief J. Edgar Hoover ordered agents in his Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) to step up operations against black nationalist “hate groups.”

COINTELPRO was a top-secret coalition put in place in 1956 during the Cold War and officially disbanded in 1971 when exposure of its unconstitutional, Gestapo-like tactics appeared imminent. It used against Hoover’s domestic targets, no-holds-barred techniques that had originally been developed for wartime use against foreign enemies. The FBI director first used COINTELPRO to disrupt and neutralize suspected American Communists. In the 1960s, Hoover employed COINTELPRO with similar zeal to go after other targets labeled subversive, including the New Left and broadly defined “black hate groups.” The shocking details later came to light through a 1970s Senate investigation — illegal wiretaps, agents provocateurs, blackmail, physical coercion of informants, and smear campaigns through FBI-friendly media. It also included murder plots and suicides goaded by threats of exposure of defamatory private information.16

Hoover did not consider anyone he labeled “subversive” to have constitutional rights deserving respect. In fact, he kept secret dossiers on politicians and celebrities of all stripes in case he felt the need to destroy their careers, too. In the mid-1960s, Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam were targets, as were Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) formed as an offshoot of Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Council.17 Equal rights for blacks threatened the status quo; Hoover spread word though sympathetic newspaper, radio and television reporters that these were all Communist fronts. Communists had, indeed, lent their support to civil rights movements for decades because they saw racism as America’s Achilles’ heel; but very few of Hoover’s targets in the civil rights movement fit that description.

By the early 1960s, civil rights champions focused on suppression of voting rights in the South as a major rallying cry; it was SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael who first used the black panther logo for an Alabama voting rights group he headed. In June 1966, Carmichael sent shock waves across country when he publicly split with Dr. King and disavowed civil disobedience in favor of championing “black power.” In her book Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African-American Freedom Struggle, U.C. Berkeley African-American Studies Associate Professor Leigh Raiford notes that inner city militants quickly adopted “black power” as “both a rallying cry and a declaration of war.”18 Allying themselves with the growing anti-war movement sweeping across college campuses, they linked racism at home with allegations of a racist foreign policy exemplified by the war in Vietnam.

In the summer of 1967, Oakland’s Black Panther Party had only just begun to attract Hoover’s attention as an upstart organization. The FBI was then still primarily focused on Dr. Martin Luther King and SNCC leaders like Carmichael and H. Rap Brown. Brown faced federal prosecution for inciting a Baltimore crowd to riot that July by announcing: “If America don’t come around, we’re gonna burn it down.”19 Rioters then set fire to local stores and began a looting rampage. Unrepentant following his arrest, Brown electrified the press by announcing that America was “on the eve of a black revolution.”20 From his parents’ living room in Oakland, Huey Newton observed television coverage of police brutally responding to rioters. Newton saw “spontaneous rebellions” by frustrated and angry youths “throwing rocks, sticks, empty wine bottles and beer cans at racist cops” as futile acts of desperation bound to result in “terrible casualties.” He published an essay in a newly-launched Black Panther Party newspaper in June 1967, arguing, “There is a world of difference between 30 million unarmed, submissive black people and 30 million black people armed with freedom and defense guns and the strategic methods of liberation.”21 At the time, the paper had barely begun to circulate locally.

It was in May of that year that the tiny new Black Panther Party for Self-Defense shocked the world by making an armed debut at the California State Capitol, protesting a proposed law to prohibit most citizens from carrying loaded weapons within city limits anywhere in the state. In early August 1967 the New York Times magazine profiled Oaklander Huey Newton as an alarming new radical leader who promoted violence against the establishment, including the execution of policemen as an act of preemptive self-defense.22

The response among many in power to both the escalating protests against the war and more urgent demands for civil rights was to become increasingly heavy-handed in attempts to crush them. In reaction, more mainstream supporters emerged in support of the constitutional rights of those the government sought to suppress and for policy changes to address the underlying issues that fueled the dissidents’ anger. Amid the heightened tension in cities across the country following the summer riots of 1967, it was all but inevitable that a spark would trigger another major clash over police brutality. The 1965 Watts riots had themselves started when angry onlookers erupted at the sight of a single, commonplace incident — a white policeman pulling over yet another black driver and impounding his car.

Less than three months after the profile of Huey Newton ran in The New York Times came headlines of an early morning shootout in West Oakland in which patrolman John Frey died and Newton and another police officer were severely wounded. Frey was the first officer killed by gunfire in Oakland in two decades. Were the Panthers signaling to inner city blacks across the country that the time had come for armed revolt? Sensing a great propaganda opportunity, the American Communist Party quickly offered to raise funds for Newton’s defense. A public relations battle soon followed, with the establishment press on one side and the underground press on the other, over who was the victim and who the aggressor, while the Panthers exploited the publicity to gain support for their revolutionary agenda.

Pioneering black media professionals like San Francisco TV reporter Belva Davis and print journalist Gilbert Moore, who covered the trial for LIFE magazine, found themselves caught uncomfortably in the middle. The Panthers’ 10-point program resonated with them even though they both disagreed with the Panthers’ extremism and glorification of violence. The Panthers soon began to attract wealthy leftist celebrities like Marlon Brando, Jane Fonda and Leonard Bernstein — among the elite later ridiculed by author Tom Wolfe as indulging in “radical chic” by embracing the Panthers’ cause. The implication was that these celebrities were naïve and silly, considering it trendy to dabble with extremists they knew little about. On the other side of the political spectrum, 1968 presidential candidate Richard Nixon focused on black militants as the target of his “Law and Order” campaign, vying with Independent segregationist George Wallace for the support of fearful white voters. The 1968 “Law and Order” campaign marked the start of the Republican Party’s famous “Southern Strategy” which has been the GOP’s electoral mainstay ever since.

Tension surrounding the upcoming Newton trial escalated after Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination in the first week of April 1968 prompted riots in cities across the country. President Johnson called out 60,000 National Guardsmen; the evening news reported that Mayor Richard Daley in Chicago ordered police to shoot to kill black rioters. A Wall Street Journal headline proclaimed that the nation was at a crossroads, with King’s death threatening a “Lasting Rift in American Society.” Its front page story noted that nonviolent efforts to bridge the racial gap were imperiled and asked: “Can America avoid two societies — one black, the other white, separated by a chasm of hate?”23

Just two days after King’s death, a group of Panthers led by ex-felon Eldridge Cleaver ambushed two Oakland policemen. The armed confrontation ended with Cleaver and his young companion Bobby Hutton attempting to surrender unarmed. Hutton died in a barrage of gunfire that also caused extensive property damage in the neighborhood. The police said they mistakenly believed Hutton still held a weapon; the Panthers claimed the police murdered the young Panther in revenge for Officer Frey’s death. The black community reacted with outrage at the police and City Hall; the press backed the angry mayor’s call for stronger police action, polarizing black and white Oaklanders even more.

Could Huey Newton get a fair trial for the death of Officer Frey under these circumstances? With a traditional white male “jury of one’s peers,” Panther supporters assumed the answer was: “Hell, no!” Nearly everyone believed Newton was headed for the gas chamber. The trial judge rescheduled his death penalty trial for mid-June of 1968. Then, the week before the trial was set to begin, the nation again reeled with news of Senator Robert Kennedy’s assassination while campaigning for President in Los Angeles. The judge postponed the Newton trial once again to July. All the while, growing opposition to the Vietnam War helped turn Newton into an anti-war icon and the Newton trial into a cause célèbre for radical groups and anti-war activists. What followed was a media frenzy amid high security never before seen at the Alameda County courthouse.

Reporter Belva Davis likened the Newton trial to a Hollywood film with perfectly cast top-notch lawyers. Each day one could expect a packed courtroom, many hundreds of demonstrators, and media from across the continent and beyond clamoring for press passes. Bay Area television and radio stations broadcast the highlights daily. National media and international papers followed the proceedings closely. LIFE magazine reporter Gilbert Moore experienced an epiphany while watching the prosecution and defense paint starkly different pictures of the confrontation that resulted in Officer Frey’s death: “Conditioned by history, both sides blinded by myth and images, moved by rage and fear . . . each in their own blind way incapable of seeing each other as human beings . . . was a tragedy in the making.”24

Hollywood could hardly have invented a more compelling movie script. A deeply politicized death penalty case with countercharges of racism against the police and prosecution witnesses makes for terrific theater, promising great division among spectators. Throw in the counsel on both sides receiving death threats and extraordinary precautions taken to safeguard the courtroom and the deliberating jury. Envision COINTELPRO wiretapping key Panthers and infiltrating their ranks with informers the whole time. Assume that hordes of police and National Guardsmen must be put on alert to quell anticipated riots. Picture the defendant as an emerging folk hero capturing the imagination not only of downtrodden members of his own race but athletes, singers and songwriters, liberal professionals, college students and antiwar activists, who have adopted him as a leftist icon. The 1968 trial of twenty-six-year-old Huey Newton was just such a screenwriter’s dream.

In the extraordinarily volatile year of 1968 the message of black militant leaders — decrying police brutality and linking it to racism in general and the quagmire of the Vietnam War — resonated the most with those outside the establishment who got their news from the underground press. Here were the Panthers bragging that they were the vanguard of the revolution. The hordes of counterculture reporters who converged in Oakland to cover the trial served an audience of impoverished urban blacks, the Old and New Left, college students, and a growing coalition of war opponents. These were “the people” Newton was talking about when he proclaimed, “I have the people behind me, and the people are my strength.”25

In mid-July 1968, when the proceedings began, one underground newspaper ran a blaring headline proclaiming “Nation’s Life at Stake.” The article explained:

History has its pivotal points. This trial is one of them. America on Monday placed itself on trial [by prosecuting Huey Newton]. . . . The Black Panthers are the most militant black organization in this nation. They are growing rapidly. They are not playing games. And they are but the visible part of a vast, black iceberg. The issue is not the alleged killing of an Oakland cop. The issue is racism. Racism can destroy America in swift flames. Oppression. Revolt. Suppression. Revolution. Determined black and brown and white men are watching what happens to Huey Newton. What they do depends on what the white man’s courts do to Huey. Most who watch with the keenest interest are already convinced that he cannot get a fair trial.26

Nationally renowned trial lawyer James Brosnahan was then a local federal prosecutor: “This trial occurred at a time when Oakland was deeply divided and entrenched, and the white community controlled almost everything, certainly controlled the press, certainly controlled all of the facilities; the courts and all of that . . . It was reasonable to believe that he couldn’t possibly get a fair trial. . . . Friction between the police department and the Black Panthers . . . had burst out in a number of different ways. All that created an atmosphere, a sort of cauldron of bias against Huey Newton.” What happened when that sea of bias was roiled by a tidal wave of American youths already alienated by the ongoing Vietnam War?

Innocence Project Co-Director Barry Scheck was a freshman at Yale in 1967–68 who then counted himself among the fast-growing hordes of Panther fans. Scheck had been campaigning hard for Robert Kennedy for President that spring: “We thought we were going to change the world.” Like millions of other Americans, Scheck found himself reeling from the twin shocks of Dr. King’s assassination and Kennedy’s just two months later. Looking back, Scheck asks: “How much more destabilizing do you want a political situation to become? . . . Many of us who had been involved in the presidential campaigns of McCarthy and Kennedy began to feel like . . . we have to take direct action. We have to go to the streets. We have to organize.” By the summer of 1968:

This trial is suddenly emerging to have enormous political significance in the country . . . You cannot understand the Huey Newton [trial] or the campaign against the Black Panther Party without really getting the feeling that the whole country was coming apart; that there really could be a revolution . . . certainly could be an insurrection of black militants . . . with weapons . . . in the streets of America. And so, many people took a look at the Black Panther Party and were terrified of it; others were inspired by it. . . . Who knew? If he was somehow acquitted of these charges [maybe] he would emerge from jail like some kind of militant Nelson Mandela.

Indeed, as demonstrators called the world’s attention to Newton’s prosecution, observers of the trial got far more drama than they expected. The two sides painted starkly different scenarios of what transpired — murder or self-defense? What seemed an open and shut case to mainstream reporters quickly proved otherwise. The jury sat spellbound when Newton turned the packed courtroom into a lecture hall on racism in America. They paid close attention when the defense produced several African-American men from West Oakland who attacked Officer Frey’s character by describing how abusive and racist he had been when arresting them for minor offenses. The jury had a choice: to accept prosecutor Lowell Jensen’s methodical case against a cop-hating revolutionary who gunned down a police officer making a routine traffic arrest, or Garry’s passionate closing argument comparing Frey’s behavior to the Gestapo tactics of the Chicago police, just seen on television bashing heads at the 1968 Democratic Presidential Convention.

The political defense that Newton and his leftist lawyers mounted became the cornerstone of the Panther Party’s recruiting efforts. Newton’s older brother Melvin Newton, now the retired Chair of Ethnic Studies at Merritt College, witnessed that trial. He marveled as his brother turned the tables and put America itself on trial for its history of racism. At the time of Huey’s arrest, the Panthers were few in number and most of them were in jail as a result of their bold Sacramento escapade. The Party even lacked an office. Melvin Newton believes to this day that, had it not been for Huey’s widely-covered murder trial, the Black Panther Party would likely have disappeared within a year of its formation. Instead, it expanded rapidly, with branches popping up across country, prompting J. Edgar Hoover in September 1968 to declare the Panther Party the number one internal threat to national security — replacing the late Dr. King.

Since the escalation of the Vietnam War in 1965, the New Left Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) had played a central role in galvanizing national student revolt. SDS grew to over 100,000 members as it led successful efforts to greatly expand the “Stop the Draft” Movement. Sitting in his prison cell since the late fall of 1967, Newton became a heroic symbol of oppression not only to young blacks across country, but to white student activists in SDS and other anti-war organizations. Both the New Left and liberal college students alike admired the Panther Party’s vehement opposition to the war and racist policies at home. “Free Huey” buttons and posters quickly spread from Bay Area protesters to hundreds of thousands of others across country then railing against the establishment. By the spring of 1969, student anti-war demonstrations had erupted at 300 college campuses amid thousands of protests nationwide.

In the summer of 1969, the most militant members of SDS split off, calling themselves the Weathermen. They incited unprecedented attempts to interfere with national commerce by acts of arson, explosions and violence reported almost daily in the media. J. Edgar Hoover focused COINTELPRO on dismantling the Weathermen and the increasingly fractious remaining SDS members. By the year’s end, the Weathermen went into hiding to continue acts of guerilla warfare as the Weather Underground while SDS officially disbanded. In the meantime, with greater ferocity, the FBI was targeting the Panther Party for extinction. By 1969, COINTELPRO agents had infiltrated the Party across country; they ratcheted up acts of sabotage against branch offices of the Party. At the FBI leader’s direction, agents made sweeping arrests, and, in December of 1969, orchestrated an armed invasion of both the Party’s Chicago and Los Angeles offices. Ostensibly, it was just Chicago police who killed Chicago Panther Party leader Fred Hampton in the predawn raid, but the highly suspicious circumstances raised alarms among both the conspiracy-minded Left and a growing number of mainstream Americans who considered respect for constitutional rights the hallmark of our democracy.

Then, in April 1970, national focus turned to the tens of thousands of demonstrators descending on New Haven, Connecticut, from across the country to protest Panther Party Chairman Bobby Seale’s upcoming murder trial on charges his supporters believed to be politically motivated — just as his recent prosecution in Chicago for inciting riots at the 1968 Democratic Convention had been. Seale was the eighth co-defendant in the internationally-followed Chicago conspiracy trial prosecuted by the federal government to jail leaders of the growing anti-war effort. History buffs know it as the Chicago Seven trial because Judge Julius Hoffman had Seale bound and gagged for backtalk and ordered that Seale be tried separately from the seven other defendants. But first, Seale would be tried for allegedly ordering a murder while passing through New Haven on a speaking tour.

Yale had never seen such activism on campus as that in opposition to the upcoming Seale trial. The instigators were anti-war Youth International Party (“Yippie”) leaders Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, joined by SDS leader Tom Hayden and other “Chicago Seven” defendants, whose own circus of a trial had just ended. In response to the Yippie-led pilgrimage to New Haven to protest the prosecution of Bobby Seale and New Haven Panther leader Ericka Huggins, President Nixon mobilized armed National Guardsmen from as far away as Virginia. J. Edgar Hoover sent agents provocateurs.

On April 15, 1970, police had confronted protesters and vandals at Harvard Square in Cambridge, resulting in extensive damage and hundreds of people injured. In an effort to defuse the situation in New Haven to prevent a repeat of what happened at Harvard, Yale’s President Kingman Brewster decided to shut down the Ivy League university for a week of voluntary teach-ins. Brewster then told the faculty, “I am appalled and ashamed that things should have come to such a pass in this country that I am skeptical of the ability of black revolutionaries to achieve a fair trial anywhere in the United States.”27 His remarks created a storm of controversy that instantly put the Mayflower Pilgrim descendant on President Nixon’s growing “enemies list.”

Although the approach at Yale won praise in some quarters as a model for incorporating the Panthers into peaceful college protests,28 angry editorials from conservative papers throughout the nation called for Brewster’s resignation for daring to voice skepticism of the American justice system. Articulating the opposite concern, Los Angeles Police Chief Ed Davis viewed the national situation in the same dire light as did J. Edgar Hoover. Testifying before a Senate committee, Davis asserted, “we have revolution on the installment plan . . . going on every day now.”29 But Brewster considered something far greater to be lost when Americans rationalized the abandonment of their core values as a society. He echoed Yale Law School Dean Eugene Rostow’s reflections eight years earlier: “The quality of a civilization is largely determined by the fairness of its criminal trials. . . .”30

So, was Brewster’s skepticism justified?

While under intense pressure from the media and polarized political factions, a trial judge, prosecutor and jury did their best to provide a fair trial to a black revolutionary in the summer of 1968. People v. Newton involved one of the most scorned revolutionaries of his day in an extremely volatile and bloody era. Was he guilty of murder as charged, or set up for a failed police ambush? By the late sixties, juries in mixed-race communities were ready to consider either possibility.

The objective of Newton’s innovative defense team was to seat as many women and minorities on the jury as possible, recognizing they would likely be most open to his side of the story. The defense lawyers broke new ground in eliminating potential jurors for bias and wound up seating — with the prosecutor’s agreement — seven women and five men, including four minorities. The defense tactics were captured in a handbook that soon became criminal defense lawyers’ “Bible” for jury selection for minority defendants nationwide.31

What did that diverse Oakland jury do with the prosecution claim of a police officer martyred by an itchy-fingered black revolutionary? How did they respond to the defense argument that the early morning shootout was just one more example in a long history of racist police brutality? Why, with the extraordinarily high tension surrounding the trial, did no urban violence erupt in its wake, as had occurred so often in the prior year? And how did the jury’s astonishing choice of African-American banker David Harper as their foreman influence the outcome of the deliberations? Harper was the first black foreman of a major criminal trial in America, a role that would still be unusual in a death penalty case today.

The Newton trial had all the ingredients to fit historian J. Anthony Lukas’s definition of “THE” trial of the century: “a spectacular show trial, a great national drama in which the stakes [are] nothing less than the soul of the American people.”32 LIFE reporter Gilbert Moore soon quit his prestigious job to write a book about the newly discovered rage inside him from his childhood in Harlem that Newton and the Panthers had tapped into. The Los Angeles Times hailed Moore’s insightful chronicle A Special Rage as “a classic document in the literature of the black-white experience in the 20th century.”33 Two decades years later it was reissued under the shortened title Rage, with a new foreword and afterword by award-winning author Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, then the University of Massachusetts’ first Afro-American Studies chairman. Thelwell was himself once a leading SNCC activist. He found Moore’s observations equally relevant to the next generation. The back cover blurb summarized why:

The Panthers represented something new on the American political landscape. Lionized by the liberal cultural elite, spied on, shot at, and jailed by the police, they brought hope to some Americans and frightened many others. Revolutionaries, outlaws, pawns, they were a cultural bridge between urban street gangs and organized civil rights groups. They filled a dangerous void. They were the militant, articulate expression of the anger and aspirations of poor young black men. That critical void exists as much today as it did in the late 1960s.34

Another 25 years later the Panthers’ mark on American history remains indelible. As historian Jane Rhodes observed in her 2007 book, Framing the Black Panthers: The Spectacular Rise of a Black Power Icon: “The passage of time has not eroded the strength of their symbols and rhetoric — the gun, the snarling panther, the raised fists, and slogans such as ‘All power to the people’ and ‘Off the pig.’ Today, representations of the Black Panthers linger in diverse arenas of commodity culture, from news stories to reality television to feature films and hip-hop, as they function as America’s dominant icons of Black Nationalism.”35 Nine years later, interest in the Panthers is far more widespread than when Professor Rhodes published her book. In 2014 the high-energy musical Party People began playing to sold-out audiences in theaters across America. With “REVOLUTION” in blazing lights as the backdrop, it engaged new generations with the fierce activism of both the Black Panthers and the contemporaneous Puerto Rican Young Lords Party in New York.36

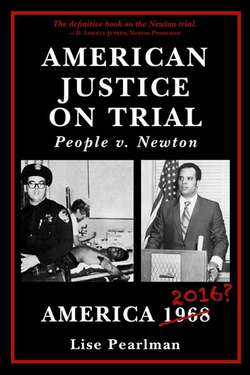

Over the intervening decades, the ground-breaking accomplishments of Newton’s sensational 1968 death penalty trial fell into relative oblivion. Its absence from the pivotal 20th century cases listed by most journalists and historians prompted me to publish, in 2012, The Sky’s the Limit: People v. Newton, The REAL Trial of the 20th Century? That book compared the extraordinary nature and enormous stakes of the Newton trial to the significant features of other headline trials from 1901 to 2000. I also addressed why I believe it nevertheless slipped from general public consciousness and wound up all but forgotten by most experts analyzing candidates for “the” trial of the American 20th century.37

Huey’s brother Melvin has a short answer: “Huey was a threat. . . . His actions were so raw and so challenging . . . his desire to be an agent for social change. . . . Dr. King wasn’t honored when he was alive and even when Dr. King was looked to as a model [it was] . . . because there were more threatening models out there . . . Huey is someone that proper authorities would like to forget. . . .”

It is gratifying that, after reading my 2012 book, more legal experts now agree that the 1968 Newton trial truly deserves to be considered one of the most pivotal trials of the 20th century. Certainly, its focus on entrenched racism in the justice system resonates today. Activists still question whether — absent video proof — juries will believe a black arrestee charging a police officer of abuse, let alone whether a black militant accused of killing a police officer can get a fair trial anywhere in America.

As we approach the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Black Panther Party, we are once again in a polarized setting. In the past year, civil rights enthusiasts in cities across the country flocked to see Stanley Nelson’s film The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution. A million more saw it on public television. (I had a cameo appearance in that film as an expert on the Newton trial.) Nelson likens the Party’s mixed legacy to the parable of the blind men and the elephant — each man describing only one feature of a complex animal.

Among other Panther-related movies in the works is a more narrowly focused documentary project for which I am on the film-making team; the project is called American Justice on Trial: People v. Newton. www.americanjusticeontrial.com. Since July 2013, award-winning film director Bob Richter and I have interviewed surviving participants and observers of the 1968 Newton death penalty trial, who offer new insights on that ground-breaking trial from every perspective: from the Panthers to journalists to witnesses, the prosecution, the police and interested bystanders. This new volume incorporates quotes from these interviewees, some of whom had never been interviewed about the trial before. I have focused here solely on the trial itself, no longer including numerous comparisons to other “trials of the century” from 1901 to 2000 as I felt compelled to do in the 2012 book. Current events have illuminated the Newton trial’s true historic significance.

In May of 2015, TIME magazine featured on its cover heavily-armed Baltimore police chasing a black suspect. Its editors asked America to consider what has changed and what hasn’t since 1968.38 President Obama recently readdressed that same issue. I invite you to read this volume and consider that question yourself.