Читать книгу AMERICAN JUSTICE ON TRIAL - Lise Pearlman - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2. OAKLAND — THE MAKINGS OF A RACIAL TINDERBOX

Оглавление“The Negro’s sounds of NOW! are not irrational demands or threats; they are a cry of desperation.”

— AUGUST 1965, EUGENE FOLEY, ASST. SEC’Y OF

COMMERCE IN CHARGE OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT1

What made Oakland in 1966 the next likely Watts? Alameda County, the seventh largest in California, occupies 821 square miles to the immediate east of the San Francisco Bay. Since 1873, Oakland has been its county seat. In 1852, when Oakland was incorporated with fewer than 1,500 people, most settled by the waterfront. After 1869, when Oakland became the terminus for the transcontinental railroad, the population began to expand exponentially, with large numbers of immigrants from Europe, most of them from Portugal and Ireland. The new arrivals also included a small percentage of Italians and Germans, African-American and Chinese railroad workers, Mexicans and Japanese immigrants. After the calamitous 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, West Oakland experienced another major growth spurt with thousands displaced from their homes across the Bay, including famed author and social activist Jack London, who had lived in Oakland as a child. Jack London Square on the waterfront now bears his name.

For entertainment, starting in the late nineteenth century, Oaklanders frequented a theme park in vice-ridden Emeryville — West Oakland’s industrialized neighbor to the north, nestled between Oakland and Berkeley. In just two square miles, the city of Emeryville managed to pack in railroad yards, saloons, gambling, dance halls and whore houses. Starting in 1903, Oaklanders could travel on Key System streetcars — the predecessor of today’s AC Transit — for work or play. Their new minor league baseball team, the Oakland Oaks, in the Pacific Coast League, was conveniently located at the Key System’s Emeryville hub, at the site Pixar Studios now occupies.

For the first few decades of the twentieth century, Oakland’s white population kept growing. The 1940 census listed just over 302,000 residents in Oakland, almost all of them whites of European ancestry. Until 1940, the black populations in Berkeley and Oakland remained relatively tiny; even fewer lived in San Francisco. This is not surprising given the historic dearth of good jobs. By 1940, Oakland listed a total of 8,462 blacks, up less than a thousand from 1930. They made up only 2.9 percent of the general population. All other minorities combined added up to only another 5,765 people.

In 1940, most minorities still lived in essentially the same areas they had occupied since the turn of the century, alongside poor white families in the flatlands of industrialized West Oakland, between Emeryville to the north and Oakland’s main business district. The only non-Caucasian racially homogenous neighborhood was Oakland’s Chinatown, one of the oldest in the country, which occupied sixteen blocks between Lake Merritt and the Oakland waterfront.

The historic white monopoly in the Oakland power structure derived from wealth and conservative politics. The well-to-do lived in upscale neighborhoods in the city’s center by Lake Merritt, on the Berkeley border to the north and in the Oakland hills to the east. Many of the most influential businessmen actually lived in Piedmont, an affluent all-white bedroom community completely surrounded by the Oakland hills. In the late 19th century, Piedmont’s white residents had simply refused to have their community absorbed by the larger city as towns like Brooklyn, Montclair Village, Fruitvale and Melrose had done.

Within Oakland itself, a Republican machine held enormous sway in politics — and the engine for that machine was the city’s newspaper of record, the Oakland Tribune. When its publisher, Joseph Knowland, added a twenty-two story tower to the Tribune building in 1923, it became for decades the tallest structure in the city. His detractors began to call Knowland “The Power in the Oakland Tribune Tower.” The anti-union lumber baron was extremely active in both state and federal politics. Knowland served as a Congressman for 11 years along with future Governor and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Earl Warren, who became a family friend. Joe Knowland’s son Bill served in the state legislature before World War II. After the war ended, Governor Warren appointed veteran Bill Knowland to a vacant Senate seat. Senator Bill Knowland would take over the reins of the Tribune in 1961 and inherit his father’s role as “the central figure in the Oakland ‘power structure’.”2

Through the 1960s, control of Oakland rested in the city council, elected citywide by the white supermajority. Joe Knowland hand-picked most of the council’s members. The councilmen chose a part-time mayor from among their group, but his function was largely ceremonial; under the city’s charter, a professional city manager oversaw all departments and reported directly to the City Council. Those who wanted to get ahead in Oakland had to make their business and political connections through the Chamber of Commerce, which Bill Knowland headed in the late 1960s, or finagle an invitation to join a prestigious service club. The club members gathered regularly for breakfast or lunch, made handshake deals and launched charitable and civic projects like the Shriners’ sponsorship of the “Necklace of Lights” around Lake Merritt strung up in the business boom of the 1920s. For most of the 20th century, practically all of the city’s power brokers met and interacted regularly in those clubs.

Since 1915, the most exclusive social club was the Athenian-Nile Club on Fourteenth Street, not far from the Tribune building. For the next several decades the Athenian-Nile Club earned its reputation as the city’s “shadow power base.”3 It was one of several “old boy” social networks like the Shriners, the Elks and Moose Lodges and Knights of Columbus. Since 1909, Oakland also had an invitation-only Rotary Club for local businessmen — just the third one organized anywhere in the world. Oakland also boasted the first Lions Club west of the Rockies.

In 1933, a group of Oakland businessmen launched the Lake Merritt Breakfast Club (LMBC) and made every mayor thereafter an honorary member. Hundreds of members representing various professions and businesses in the community got together weekly for breakfast to network and socialize at a restaurant overlooking the lake. LMBC members launched Oakland’s Children’s Fairyland theme park in 1950 (the main inspiration for Disneyland) and later spearheaded the restoration of the “Necklace of Lights” that had gone dark during World War II — “Oakland’s jewel,” which has become the city’s iconic image ever since.

For decades, West Oaklanders had no seats at the table. The business and community leaders LMBC welcomed to its roster resembled the membership of other elite men’s clubs in town. As of the late 1960s there were only one or two Jewish members, one pioneering Japanese-American city councilman (a Republican) and no blacks. Steve Hanson, a fourth generation Oaklander and future president of LMBC acknowledges that “the club had its political agenda, which was very conservative,” even in the midst of the turbulent sixties. No women gained membership in any of these old boys’ clubs until the late 1980s — and only after the courts stepped in to outlaw their male-only policies.

In the decades preceding World War II, West Oakland’s Seventh Street was a bustling place. Before completion of the Bay Bridge in 1936, the electric Key Train System carried commuters along Seventh Street to a ferry to San Francisco. Black professionals opened up offices along Seventh Street, but at night, vice predominated. Near the railroad yards bordering Seventh Street were pawn shops, houses of prostitution, blues clubs, bars, barbeque joints and gambling establishments. The renowned Pullman porters, many of whom lived nearby because the railroad had its terminus in Oakland, called their gambling parlor “The Shasta.” Until the 1960s, only black men served as Pullman porters. These were much-coveted jobs. Among their leaders was C. L. Dellums, the uncle of Ron Dellums, longtime East Bay congressman and, from 2007 to 2011, Oakland’s mayor. In 1925, overcoming stiff opposition, C. L. made history, along with A. Philip Randolph, when they established the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the nation’s first chartered black union. The porters played a pivotal role in launching the black middle class in America and setting the groundwork for the civil rights movement. That history of local political activism would also make West Oakland fertile ground for the Panther Party.

Among the movers and shakers in West Oakland between World War I and World War II, one especially colorful entrepreneur stood out: Charles “Raincoat” Jones, a veteran of both the Spanish-American War (as an infantryman) and World War I (as a cook), who made most of his fortune moneylending and running gambling rooms. By the late ’20s, Jones (who always wore a mackintosh) reputedly owned the entire block of buildings abutting Seventh and Willow, the corner where the October 1967 shooting would occur. Jones and a small group of successful business friends made it a point to support enterprises that the black community needed, such as by providing start-up money for a pharmacy or a timely loan to help save San Francisco Sun Reporter publisher Dr. Carlton Goodlett from having to close his newspaper’s doors.

Before World War II, vice peddlers like Raincoat were able to maintain a “live and let live” relationship with the police. Raincoat was happy to pay protection money, which his attorney, Leonard Richardson, then the most prominent African-American lawyer around, hand-delivered by messenger directly to a police captain in City Hall each Friday.4 Whenever police raided Raincoat’s gambling room, he pulled out his wad of bills and bailed out whoever got arrested. But that peaceful coexistence rested on a relatively stable minority population that did not threaten the status quo.

As Bay Area industries geared up for the war effort in 1941, black-white relations began to change for the worse in a hurry. White unions collaborated with management to freeze black workers out of steady jobs. Discrimination became so pervasive that local black labor organizers joined with white civil rights leaders to plan a march on Washington to compel equal job opportunities. Roosevelt had wooed African-Americans from their traditional home in the Republican Party with his New Deal programs. He avoided the embarrassment of a major civil rights protest by issuing Executive Order 8802 in 1941, an unprecedented presidential decree that forbade discrimination on grounds of race, color or national origin in hiring workers for the national defense program. Kaiser Shipyards then recruited heavily in the South, encouraging a mass migration of blacks.

Some hailed Roosevelt’s order as “the breakthrough of the century in the Negro’s battle for civil rights”; others recognized it as but one of many hard-fought milestones over the prior several decades.5 Unequal pay and other discriminatory employment practices in the defense industries continued despite the executive order. Yet conditions in Oakland were far better than in the South. In the first three years of the war, over 320,000 blacks migrated to the Bay Area. Berkeley created an Emergency Housing Committee to help find lodging for the new arrivals. Civil rights advocates like African-American pharmacist William Byron Rumford went further. They formed an inter-racial welcoming committee to help families from the South adjust to their new environment.

Many came from the rural south by the trainload and, for the most part, found housing only in the most undesirable locations. In Berkeley, that meant the flatlands below Shattuck Avenue. In Oakland, they poured into similarly neglected neighborhoods, mostly in West Oakland. Low-rent housing complexes first opened in West Oakland in 1941 as a wartime redevelopment project, but they were woefully inadequate. West Oakland “began to overflow.” One Oakland resident remembered: “We’d go down to the 16th street station after school to watch the people get off the trains, and it was like a parade. You just couldn’t believe that that many people would come in, and some didn’t even have luggage; they would come with boxes, with 3 or 4 children with no place to stay . . . and they would ask everyone if they had any place to stay or could they make some space into rooms.”6

A race riot broke out on a Key System train in downtown Oakland in 1943. It was inspired by the “Zoot Suit” riot in Los Angeles, where white servicemen had attacked Mexican-American immigrants wearing the showy, wide-lapelled Zoot suits with padded shoulders that first became popular with African-American and Italian men. The amount of cloth that went into Zoot suits was considered extravagant during wartime and criticized as unpatriotic. Similar “Zoot Suit” riots occurred in other cities, involving white soldiers attacking blacks. The Oakland riot grew to a mixed race mob of 2,000. A local newspaper, The Observer, commented:

That riot on Twelfth Street the other day may be the forerunner of more and larger riots because we now have (a) a semi-mining camp civilization and (b) a new race problem, brought about by the influx of what might be called socially-liberated or uninhibited Negroes who are not bound by the old and peaceful understanding between the Negro and the white in Oakland, which has lasted for so many decades, but who insist upon barging into the white man and becoming an integral part of the white man’s society.7

By 1945, four times as many blacks were counted in the official Oakland census as in 1940. Shortly after the war’s end, a professor at the University of California’s School of Social Work observed that “Negroes are rapidly becoming the most significant minority group in California.”8 The Oakland establishment not only feared the mass of new black residents; it had for decades waged a running battle with white labor unions. There had been major bloody strikes during the Depression, but a moratorium on strikes during World War II. Then in early December 1946 several hundred women retail clerks picketed two downtown Oakland department stores for equal pay and a union contract. The Alameda County Central Labor Council followed up with a call for a walkout by all of its members until union demands were met. Over the next two days, strike supporters went on a self-declared “work holiday” mushrooming to over 100,000 people enjoying a respite from work — more than a quarter of the city’s population. Within 24 hours, the walkouts shut down most businesses in downtown Oakland, leading the City Council to declare a state of emergency and put tough-minded Mayor Herbert Beach in direct charge of the police and fire departments.

The heavy-handed treatment of these hordes of protesters would be mirrored in the 1960s, for similar reasons — Mayor Beach saw this general strike as an attempted revolution. He quickly hired beefy strikebreakers to supplement the police. “[S]ome 200 Oakland and Berkeley police, many in riot gear, swept down the street. They roughly pushed aside pickets and pedestrians alike as they cleared that block and the surrounding eight square blocks. They set up machine guns across from the stores, while tow trucks moved in to snatch away any cars parked in the area.” Standing protected on the sidelines, nodding their approval, were the key local men in power, bent on crushing this populist uprising: the police chief, city council members, representatives of picketed department stores and, of course, the anti-union group’s acknowledged leader, Joseph Knowland of the Oakland Tribune.9

It would be Oakland’s last general strike. Yet Mayor Beach’s temporary dictatorship caused a backlash. It ushered in a change to Oakland’s charter to have the mayor elected directly by Oakland’s citizens, independent of the city council. Even so, the mayor’s role remained largely ceremonial. West Oakland still lacked any influence as businessman Clifford Rishell won the 1949 election and became known as “Ambassador of Goodwill for Oakland” and “Oakland’s Super Salesman” — the man who brought in the Oakland Raiders football team. Meanwhile, Mayor Rishell and the city council ignored the growing slums of West Oakland.

During World War II the government constructed temporary housing for black shipyard workers and their families near the Navy Yard in the island city of Alameda, a nearly all-white town separated from Oakland by the Oakland Estuary. Shortly after the war ended, that government housing was bulldozed, forcing most of the suddenly unemployed black workers to relocate to West Oakland, which was already overcrowded. The project was billed as “urban renewal” but West Oaklanders knew it as “Negro removal,” intended to reestablish the city of Alameda’s nearly all-white status.10

The situation only got worse in the 1950s when ground broke for the double-decker Cypress Freeway, designed to connect the San Francisco Bay Bridge to the Nimitz Freeway in Oakland. The new connector bisected West Oakland and separated it from the city center. City Hall had no compunction about razing homes and displacing West Oakland residents to accommodate this progress. Nor, over most of the next two decades, did the City Council concern itself with addressing that broken community’s chronic unemployment, dilapidated housing and overcrowded, underachieving schools. The problem required too much money for locals to address on their own in any meaningful way, and the officeholders did not consider government the answer.

In the 1940s, members of Oakland’s growing black middle class opened their own branch of the NAACP to address community concerns. By the 1950s, the NAACP was inviting black youths to the West Oakland community center to plan their own activities. The adult council focused on gradual empowerment. They taught the teenagers Robert’s Rules of Order to conduct their own meetings and reminded them that Oakland’s Juvenile Hall was just across the street. Kids could either learn how to work within the system to make change or wind up in Juvenile Hall.

The Oakland branch of the NAACP did not just challenge discrimination in the courts. It also organized picketing of City Hall to call attention to blatant exclusionary practices by white businesses and homeowners in their own backyard. Much as in the South, blacks could not eat in most restaurants in downtown Oakland or shop at a dime store or sit at a lunch counter, much less buy or rent a home in a white neighborhood — their movements were almost completely circumscribed. Bill Patterson, who later became President of the Oakland NAACP, moved to West Oakland from Arkansas in the early 1950s, a teen-aged athlete who took the long train ride to join relatives in Oakland to fulfill his ambition to go to college. Now in his eighties, he vividly recalls what it was like back then: “The police department . . . if you traveled outside of your sector, you got stopped. Today they have a new name for that — they call it profiling — but it happened back then as a regular thing, because in neighborhoods that were all white, there was fear, you know, of black people. . . . Many of them just didn’t know black folk.”

Essentially, blacks needed a passport to get into white enclaves. In the early 1960s, the Oakland NAACP president was a rare black who still lived in the adjacent City of Alameda. Whenever he invited visiting civil rights leaders to his home — including the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. — he called the police ahead of time so the visitors would not be stopped for questioning as they crossed the bridge from Oakland.

Wall Street lawyer Amory Bradford, author of Oakland’s Not for Burning, was a former Ford Foundation consultant whom the Johnson administration tapped, in late 1965, to help launch a multi-million-dollar pilot jobs-program in Oakland. He and his colleagues from the Economic Development Agency (EDA) had as their mission to prevent another ruinous riot like the one that had just devastated Watts. When Bradford arrived from Washington, D.C., with other EDA emissaries, he could see that “a dangerous deadlock had developed between the Oakland ghetto, which was demanding a better way of life, and the business and government establishment, which was determined to maintain order in Oakland and to improve its economy, but was unable to provide the resources to meet ghetto needs. Without outside help, this deadlock seemed certain to produce an explosion. . . . The community had become fragmented into hostile, distrustful [warring] groups.”11

Bradford met early in 1966 with Oakland’s “leaders in business, in the city and in the port . . . men with the power to solve Oakland’s problems if the federal government provided key resources.” He noted, “This group was Republican, mostly conservative . . . Chamber of Commerce–oriented [and] . . . instinctively distrustful of Federal spending programs . . . .” These local powerful men were extraordinarily sensitive to outside criticism. National media from the Wall Street Journal to TIME and Newsweek had already zeroed in on Oakland as “a failed city plagued by racialized poverty and unemployment.”12

There was much to resent in these disparaging accounts. In 1962, Oakland had expanded the capacity of its 35-year-old port. In the process, it became the first city on the Pacific Coast where container ships could dock. The port was soon handling the second highest tonnage of cargo shipments worldwide. By 1966, two mammoth construction projects were taking shape along Seventh Street in West Oakland: a new transbay tube to San Francisco for the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) rail system and a huge new main post office. Yet, many homes and businesses were razed in the process, leaving gaping construction zones adjacent to dilapidated Victorians that reflected a long-gone, more prosperous era.

Among the recent building projects was also a new multi-story police headquarters at Seventh and Broadway. Black youths arrested on the streets of West Oakland became all too familiar with its basement jail cells. Civil rights lawyer John Burris was a local teenager at the time: “Back in the 1960s . . . what you really had was this sense of white officers . . . occupying the African American community in law enforcement. . . . You did not trust the police at all.”

Morrie Turner — a protégé of “Peanuts” cartoonist Charles Schultz — would become world-renowned in the 1970s for creating the first integrated comic strip, “Wee Pals.” Turner was the son of a Pullman porter. He made his living in the 1960s as a rare African-American clerk in the Oakland Police Department. At night, Turner followed his passion, penning civil rights cartoons for African-American newspapers and magazines and sketching signs for the local NAACP. By day, Turner typed up police reports from white officers who described African-American arrestees as “male, nigger.” Morrie would correct them, repeating “male Negro” as a form of protest. There was no question in Turner’s mind — the police he worked with were bigoted. Once he took a phone message meant for a white co-worker — “The niggers are taking over Oakland.”

When Turner’s co-workers looked out the window and saw NAACP picketers, they would call to him to come see the Commie protestors. Turner wisely did not mention that the signs they carried were his design. Too often police reports described male suspects who had to be physically restrained or shot. He could not imagine so many arrestees had invited such harsh treatment. He concluded that the officers simply backed each other up as cover stories to justify so many bruises and injuries to the black men they hauled in or, occasionally, to explain away their deaths.

By 1966, Oakland’s population was over one-fourth black and thirty percent minority. White flight had turned much of North Oakland into transitional neighborhoods with black residents moving in and whites moving out. African-Americans still occupied West Oakland; East Oakland remained dominated by people of Portuguese descent as it had been for several decades. One exception was the Fruitvale District two miles southeast of Lake Merritt, which was becoming mostly Mexican-American. A large area near the 40-year-old Oakland airport was in the process of turning into another black ghetto. Starting in the early ’60s, whites began moving to more homogenous communities further south in the county and blacks from West Oakland moved in.

Like Seventh Street in West Oakland, East 14th Street became the main thoroughfare through East Oakland. By 1966, East 14th Street had become a “garish strip of shops, bars, poolrooms, and dance halls” attracting young Latino and black clientele. To Ivy-Leaguer Amory Bradford, these youths seemed “poised on the edge of trouble.”13 Bradford saw some hope for salvation with job creation; most police on the beat simply saw them as budding juvenile delinquents.

The divide between police and minority communities was exacerbated by police patrolling in cars rather than walking beats on foot as they had once done. When Bradford and other white federal officials first met with black neighborhood leaders in West Oakland in early 1966, Bradford noticed how “the introduction of the ‘prowl car’ widened the gulf between police and people.” The mixed race group of adults had gathered on a sidewalk while awaiting a key to the hall where they had come to discuss the proposed new jobs program. Bradford saw his black companions grow tense as a patrol car circled the block a number of times studying them, never stopping to ask what was the problem or to offer assistance.14

For Mexican-Americans the situation in East Oakland’s flatlands was similar. Future Alameda County Judge Leo Dorado recalls, as a teen, policemen stopping him on his bicycle headed across the bridge to a public beach in the town of Alameda: “I was clearly stopped because I was a brown face from Oakland in Alameda . . . It was . . . the way it was . . . I was very aware that Alameda was completely white.” Dorado explained: “From the time I was young . . . the Oakland police . . . had a very strong presence in all of my neighborhoods. Everyone had stories. . . . It wasn’t all negative, but the lines were clearly drawn that the Oakland police were in charge of what was going on in the neighborhoods. And as long as you didn’t get on their bad side, their wrong side, then you’re okay. If you did, then you are in trouble . . . you are going to be physically handled before they took you to where they were going to take you.”

In the spring of 1966 minorities in both East and West Oakland had a somewhat sympathetic new mayor who promised to listen to their concerns. John Reading was a self-made millionaire who had moved to Oakland as a young teen. Reading worked his way through the University of California (“Cal”) before spending six years in the Army Air Corps, where he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel. After World War II, Reading expanded his father’s grocery business, which became famous for its frozen “Red’s Tamales” packaged in company plants in Mexico and East Oakland. In just a couple of years Mayor Reading would become the Panthers’ chief nemesis, but when sworn in in April 1966, his first instinct was to convince West Oaklanders that someone at City Hall would finally work with them to support major improvements in their community.

Reading’s Republican fellow council members elected him in February of 1966 when the incumbent John Houlihan abruptly resigned after being caught embezzling from a law firm client. Houlihan later spent two years in prison. Reading figured the other council members valued his problem-solving skills and business success. He did not consider himself a career politician, but was willing to devote himself full-time to the “thankless job” of mayor, which offered only token part-time pay and little power.15 His predecessor Houlihan had been a lawyer for the Oakland Tribune. Houlihan’s gruff manner probably resembled that of his father, a San Francisco policeman. Black leaders considered Houlihan “an arrogant, impatient man” who enjoyed imposing the will of “the power structure” on the powerless.16

Reading promised dubious West Oakland leaders a new “open door” era at City Hall and vowed to “listen to anyone who wants to come in and talk to me.” To launch his new policy of free-flowing communications between City Hall and West Oakland, Reading agreed to an interview with a new African-American newspaper, The Flatlands, started by two enterprising young women. Its motto was “Tell it like it is and do what is needed.” Its first issue presented a grim and angry picture of the city: “Welcome to Oakland, the all-American city; welcome to Oakland, the ‘city of pain.’ Most of the well-to-do whites and a small number of well-to-do Negroes live in the Oakland hills . . . They look down onto a patchwork of grey . . . where the flatlands are . . . spilling over with people. The flatlands stink with decay . . . The flatlands people have had no one to speak for them.”17

Mayor Reading gave honest answers in his interview. Critics coming to voice concerns at City Council meetings would be afforded “respect, dignity and courtesy,” a decided change from mayors past. Reading understood the urgency of the situation in the spring of 1966 and squarely addressed the issue on so many people’s minds: “Is Oakland going to blow?” The Mayor acknowledged: “Unless more is done, quickly, we can have real trouble here in Oakland, anytime.”18 He admitted to the paper’s editorial board that, as a member of the establishment, he expected them to view him with suspicion.

Of course, the real power lay in the City Council majority, which remained intransigent. Nonetheless, Reading began to make inroads, working closely with African-American urban planner John Williams, the talented head of Oakland’s Urban Renewal Agency. Reading also tried to broker a compromise when Oakland’s Poverty Council and its community relations chair Judge Lionel Wilson first proposed an advisory police review board. Appointed to the bench six years earlier by Governor Pat Brown, Wilson was still the only African-American judge in the county. He had started out as a political protégé of East Bay Assemblyman William Byron Rumford, the first black elected to the state legislature. Judge Wilson’s proposal for community police review went down to defeat at the hands of the adamantly opposed City Council majority. Not until 1980 would such a review board be established — during Wilson’s tenure as Oakland’s first black mayor.

While Oakland remained free of any major incidents in the summer of 1966, riots broke out in San Francisco as well as Chicago, Brooklyn, Cleveland and Louisville. As in Watts in 1965, what prompted four days of looting and burning of warehouses in San Francisco’s Hunter’s Point and the Fillmore District that September was a single inflammatory incident. This time it was the death of an unarmed sixteen-year-old named Matthew Johnson, whom a policeman had shot as a suspected car thief. When officers arrived to stop the looting that followed, they faced sniper fire. Rumors spread that militant blacks in Oakland were stockpiling homemade Molotov cocktails and stashes of arms to launch similar violence. Federal officials worried that it might not prove feasible to save Oakland from exploding next.

West Oakland community leader Curtis Baker was among the original doubters who came to trust Mayor Reading to represent the community in convincing the EDA and Department of Commerce in Washington that devoting federal resources to a multi-million dollar jobs program in Oakland was worth the risk. Baker distributed mimeographed flyers urging others to keep the faith. The Flatlands paper soon folded for lack of funds, but the federal jobs program went forward. In the summer of 1967 when riots erupted in cities across country, remarkably, none happened in Oakland. At about the same time, Mayor Reading lured a major league baseball team, the Kansas City A’s, to Oakland beginning with the 1968 season, and decided he would run for election.

The widespread riots during the “long, hot summer” of 1967 prompted President Johnson to order a blue ribbon panel to study its root causes. Chaired by Illinois governor Otto Kerner, the commission and the report it produced were both commonly referred to by his last name. The Kerner Report, which became a best-selling book, zeroed in on the lack of diversity in police forces across the country as a major societal problem. The panel placed most of the blame for urban unrest on “[w]hite racism . . . for the explosive mixture which has been accumulating in our cities since the end of World War II.”19 The panel also criticized the press for reporting the news through “white men’s eyes.” It warned that the nation was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal” and proposed controversial major investments in the nation’s inner cities like the pilot jobs program in Oakland.20

Lyndon Johnson made the war on poverty a top priority, but the home front was only one crisis he faced in the fall of 1967. The other was escalating opposition to a war in Vietnam that was looking less and less winnable. What grew most worrisome for Washington was the convergence of the two anti-establishment movements — mostly white war protesters and mixed-race civil rights demonstrators. FBI Director Hoover became especially alarmed in April 1967 when Reverend King called for the United States to declare a unilateral cease fire in Vietnam and bring the troops back home to promote justice and “the service of peace.”21

By this time, Hoover considered the gifted orator the most dangerous man in America. Now King was openly using his moral authority to pressure the federal government to end the war and redirect those same resources to address longstanding civil rights grievances at home. More radical activists, including SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael, echoed — and amplified — the sentiments of King’s speeches. Carmichael derided the war as “white people sending black people to make war on yellow people in order to defend the land they stole from red people.”22 In their first public statement in May 1967, the Panthers similarly condemned the war as an act of racist colonialism mirroring centuries of genocidal practices at home.23

Starting in the fall of 1964 when protesters on the Berkeley campus launched the Free Speech Movement (“FSM”), students joined with outside activists to turn the public against the war in Southeast Asia by staging numerous sit-ins, marches and teach-ins. They also plotted aggressive action to disrupt the arrival of troop trains at the Oakland Army Terminal. All the while, the FBI was not only tracking FSM leaders closely, it had embedded agents in the Movement. Journalist Seth Rosenfeld’s best-selling 2012 book, Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals and Reagan’s Rise to Power, focused particularly on the FBI’s activities at the University of California vis-à-vis the FSM in the 1960s. Rosenfeld says: “One of the most surprising findings in my research was the extent to which the FBI had infiltrated every level of the campus community, from student organizations to faculty to administrators to the Board of Regents.”

The lead lawyers later involved in Huey Newton’s defense were among the radical members of the Old and New Left the FBI had already been tracking. In the early sixties the FBI focused on East Bay’s Friends of SNCC, headed by Jessica Mitford’s daughter. It was one of the primary fundraisers for SNCC in the country. The FBI also maintained a file on the San Francisco Lawyers Guild, which sent lawyer volunteers to help staff Freedom Summer in Mississippi and Alabama in 1964 to register black voters and defend arrested civil rights workers. So when the Free Speech Movement began in the fall of 1964, the FBI was already keeping dossiers on the activists who would lead it.

The Free Speech Movement started out nearly all white — in Berkeley, you could then count African-American student activists on the fingers of two hands. Students on college campuses across the country soon began staging hundreds of their own protests, as did activists in the nation’s largest cities. Filling a role that radical bloggers would assume several decades later, new underground newspapers like The Berkeley Barb and San Francisco’s The Movement ran stories that countered, and often ridiculed, establishment media coverage of erupting anti-war activity.

The third week of October 1967 marked a major, two-pronged initiative. In coordination with a planned march on the Pentagon, a coalition of Bay Area activists launched “Stop the Draft Week” — several days of massive demonstrations designed to shut down the Oakland Induction Center, one of the largest such facilities on the Pacific Coast. The police geared up too, with all officers assigned to 12-hour shifts for 24-hour coverage in anticipation of a major assault on the induction center. On the first day, some three thousand protesters blocked the center’s entrance, leading to more than a hundred arrests. The following day twice as many demonstrators blocked the doorway and the surrounding streets. An estimated 250 Oakland police, sheriff’s deputies and highway patrolmen broke through and dispersed the crowd, spraying mace and swinging batons in a bloody confrontation that injured many protestors.

The stand-off with white students amazed West Oakland blacks who had thought head-bashing was not something police did to whites. It also surprised them to see privileged college students standing up to the police to risk injury for a cause they believed in. Belva Davis covered the melee as a young reporter for a San Francisco TV station. She knew she was witnessing history: “The Bay Area felt like ground zero in a generational battle for the soul of the country.”24

City officials were just as indignant as the protesters; while the crowds railed against injustice, the city’s leaders ranted about the disruption and chaos. Businessmen at their club breakfasts and lunches deplored Oakland’s growing notoriety. District Attorney Frank Coakley brought conspiracy charges against key planners of the anti-war protest; the county’s top prosecutor D. Lowell Jensen would eventually try them together as “The Oakland Seven.” A team of three defense lawyers, headed by Lawyers Guild veteran Charles Garry, quickly assembled. The defense team audaciously planned to invoke the Nuremberg Principles as their clients’ justification for blocking entrance to the induction center. They wanted to make the case that the Vietnam War was a crime against humanity — and put the war itself on trial.

It was hard to imagine at the time that another Oakland arrest would generate enough coverage and controversy to drown out the noise surrounding the “Oakland Seven,” while pitting the same lead counsel against one another — with the police and establishment on one side, and anti-war activists joined with civil rights protesters on the other. Just two weeks after “Stop the Draft Week” came the spark Hoover dreaded that would merge two protest movements on a shared goal: the synergy of anti-war and civil rights activists that Dr. King urged in 1967 on a national stage got a powerful boost from a single bloody confrontation in the very same city where the Oakland Seven would be tried.

In his book Oakland’s Not for Burning, published in mid-1968, Bradford noted: “Oakland, to its credit, came through 1966, 1967 and the first half of 1968 without a serious [race] riot. But, like all our cities, it will remain in precarious balance, on the edge of violence, until far more than is now in view can be done to improve life for those who dwell in the ghetto.”25 Bradford omitted from his book any reference whatsoever to the headline-grabbing West Oakland shooting on October 28,1967, which left Officer John Frey dead and Huey Newton and one other officer seriously wounded. At a time when the FBI was treating the Panther Party as a growing threat to national security, Bradford gave the Panther Party only brief mention in his book on fragile race relations in Oakland, calling the Panthers a “militant group of young Negroes, which had become active in Oakland in 1967, operating patrols to follow police cars and to advise those arrested in the ghetto.” Bradford referenced only a single shootout between a dozen or so Panthers and the police in April of 1968 that “seemed likely to trigger a riot,” but did not.26 The shootout was the one that ended with the police killing unarmed teenager Bobby Hutton.

Bradford’s omission from his book of the polarizing Newton murder case was telling. The looming outcome of that death penalty trial — covered daily on the front pages of local papers and on the evening news — was a glaring and obvious source of enormous tension. Bradford had to have seen the historic security measures at the courthouse where uniformed Black Panthers in their late teens and early twenties urged on unprecedented crowds of mixed race protesters with chants like “Revolution has come. Time to pick up the gun.” Black youths from the flatlands had found a voice they felt spoke for them, a seemingly fearless voice backed up with arms and ammunition.

With full-throated support from the business community and the Oakland Tribune, Mayor Reading repositioned himself on one side of a new and bitter chasm dividing City Hall and the black community, the police and the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense — vanguard of the revolution. Amory Bradford published his book, not in triumph that the federal government’s intervention had averted another Watts, but in guarded hope that Oakland truly was not for burning.

Oakland Post Collection, MS169, African American Museum and Library at Oakland, Oakland Public Library, Oakland, CA.

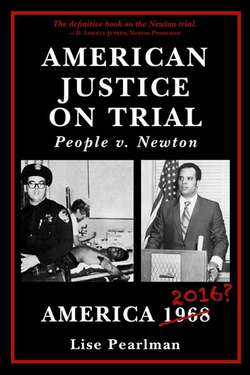

Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party.