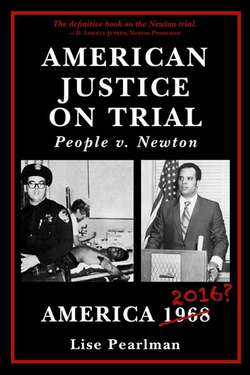

Читать книгу AMERICAN JUSTICE ON TRIAL - Lise Pearlman - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1. FREE HUEY NOW!

ОглавлениеPushed into the corner Of the hobnailed boot, Pushed into the corner of the “I-don’t-want-to-die” cry, Pushed into the corner of “I don’t want to study war no more,” Changed into “Eye for eye,” The Panther in his desperate boldness Wears no disguise, Motivated by the truest Of the oldest Lies.

— LANGSTON HUGHES, “BLACK PANTHER”

A newspaper photographer wormed his way past police guards into the Kaiser Hospital emergency room and snapped a quick photo before being ejected. That afternoon’s front page displayed black militant Huey Newton lying bare-chested, a bullet wound in his abdomen, his hands shackled to a hospital gurney. A nurse stood in the background. The original photo showed another figure before it was cropped for publication. In front of Newton stood one of his police guards, dazed by the unexpected click of a camera. On the morning of October 28, 1967, Oakland police had put out an all-points bulletin for Huey Newton following a pre-dawn shootout in West Oakland’s red light district. As co-founder of the Black Panther Party, Newton was already well known to local law enforcement, infuriating them with his official title, Minister of Defense. Police immediately suspected Newton of killing Officer John Frey and wounding Officer Herbert “Cliff” Heanes, who now lay hospitalized in critical condition with gunshot wounds in the chest, knee and one arm. Police headquarters released pictures of the young policemen to the press and mentioned that both were fathers: Frey had a three-year-old daughter; Heanes had a two-year-old and ten-month old.

The police stormed Newton’s parents’ home in Oakland looking for Huey to no avail before they got word the Panther leader was at Kaiser Hospital. Shortly before dawn, Newton had staggered into the emergency room with a bloody rag clutched to his stomach. The middle-aged blond nurse on duty, Corinne Leonard, heard a car door slam and the car drive off, but did not see who deposited Newton outside. The police later thought that it might have been Newton’s girlfriend. They knew that a young black woman later stopped by the hospital, but left before she could be questioned.

The police had confiscated the tawny 1958 Volkswagen sedan registered to LaVerne Williams that Newton was driving early that morning on Seventh Street when Officer Frey pulled him over. At first, the police assumed LaVerne was the male passenger who had accompanied Huey in the car and fled the scene with him soon after the shooting. The next day, Oakland attorney John George told the police that he represented aspiring singer LaVerne Williams, Newton’s 22-year-old girlfriend, who worked at an office of the newly-established Job Corps. LaVerne acknowledged she was the young woman who had visited Newton in the hospital, but had only learned of his whereabouts from an anonymous phone call.

Newton’s passenger still remained a mystery. At the hospital, Newton quickly created a stir by shouting for prompt medical care while refusing to sign hospital forms. Although he was in agony from the bullet wound, Newton had mustered the energy to withdraw some notes from his wallet, tear them to pieces and throw them in the trash. It had not been his idea to go to the hospital. He had wanted to die among his close friends in the neighborhood. Though the bullet in his abdomen had not hit any large blood vessels, it had punctured his intestine. Nurse Leonard did not realize that peritonitis would kill Newton if the doctors did not operate on him immediately. The small size of the wound caused her to underestimate the seriousness of his condition. Frightened by Newton’s belligerence, she called the police before she summoned a doctor.

The police arrived at the hospital emergency room less than half an hour from the nurse’s call, shortly after the doctor arrived and had Newton placed on a gurney. Newton screamed in pain and spat blood as the officer slapped handcuffs on his wrists, shackled him to the gurney and recited his Miranda rights. Newton was still shouting obscenities at the police as the doctor wheeled him off to surgery, while barking at Newton to shut up. Listed in fair condition following surgery, Newton was transferred to Highland Hospital and placed under 24-hour guard by six policemen armed with shotguns.

Meanwhile, after the startling police invasion of his home, Huey’s father, Walter Newton, got dressed and headed over to his son Melvin’s apartment in North Oakland. That insistent early morning knock on his door was something Melvin would never forget. Melvin found the news shocking, but not a surprise. Huey had been involved in armed confrontations with police before. By then, Walter Newton knew that Huey was headed into surgery at Kaiser Hospital following a shootout with two policemen at Seventh and Willow streets. Since it was a Saturday when Walter roused Melvin, Melvin did not need to head to his job supervising Alameda County social workers. He immediately got dressed and went down to the scene of the shooting, not sure what he expected to find. Melvin walked through the area, but found nothing. He soon learned of Huey’s transfer to Highland Hospital. Melvin and his father visited Huey in a recovery room there — awake and complaining that police had shaken his bed and threatened his life.

Panther recruiter Earl Anthony was listening to soul music on the radio before dawn on the 28th when the announcer interrupted with a bulletin about the shootout. Anthony’s assumption was that the “lousy Oakland police . . . had tried to set up brother Huey.”1 Anthony had accompanied Newton on the evening of October 26, two nights before the deadly incident. They started off at the Cleavers’ apartment where Newton made a comment Anthony would never forget. They were talking about a passage from the book Look Homeward, Angel in which author Thomas Wolfe wrote about crossing a river and not being able to return. That struck Huey as similar to dedicating yourself to fight for black liberation and never being able to accept inferior status again.2 The two left the Cleavers to go see writer James Baldwin, who was then in town, and provide him with several copies of the Black Panther paper. They ended up bar-hopping in Oakland before Newton drove him back to San Francisco. Anthony would not see Newton on the streets again for more than a decade.

Emory Douglas had often traveled around with Huey Newton and David Hilliard over the preceding three weeks, organizing support for the Panthers at bars and social events. At the time, Douglas was not yet devoted full-time to the Party. On the night of October 27, 1967, both he and David Hilliard begged off. Douglas had already agreed to monitor a dance. Hilliard had set up a late-night poker game fund-raiser for Party Chairman Bobby Seale’s bail to gain Seale’s release from jail after serving his sentence for the minor charges resulting from the Panthers’ armed trip to Sacramento in May. Newton got another good friend to accompany him instead. The next morning Douglas woke up to a predawn call from Hilliard; Newton had been shot and a policeman was dead. Douglas was stunned. He hoped Newton would hang on, but also realized the bleak prospect that would attend his survival. Newton would face murder charges and likely execution. Emory Douglas also had to know how close he came to winding up in the same predicament.

Panther recruit Janice Garrett first heard about Newton’s shootout on her car radio crossing the Bay Bridge to San Francisco from Oakland with her roommates. “We were in shock. . . . We went right to our apartment. We didn’t know how extensive his wounds were . . . couldn’t get any information. Everything was very chaotic and we were very scared at the time because we didn’t know what the police were going to do.” They soon found out that Huey was in the hospital with a stomach wound, but had survived the attack. By then, they also knew that one of the policemen was dead and another wounded. For Garrett, it was “very, very upsetting to see him [in the newspaper photo] in that position handcuffed to the bed because we knew he had to be in excruciating pain.” As foot soldiers for the Party, they knew “we had to get busy and contact other Party members so that we could find out what the next strategy was, how are we going to get help for Huey.” The answer from David Hilliard and Eldridge Cleaver was to get their side of the story out in the Black Panther newspaper as soon as possible — that Newton had been set upon by the police — and remind their readers what the Black Panther Party stood for.

Eldridge Cleaver had secretly joined the Black Panthers in the spring of 1967 as its Minister of Information, while pretending to cover the group solely as a reporter for Ramparts. At the time, Cleaver could not publicly admit his membership because he was still on parole and prohibited from associating with “undesirables” like the Panthers. In the early predawn after the October 28 shootout, Cleaver took the risk of declaring himself the acting head of the Black Panther Party. Bobby Seale, co-founder of the Party, was still behind bars at the Santa Rita County Jail. By October’s end when Newton was arrested, the fledgling group was in near total disarray, lacking even a headquarters.

San Francisco Lawyers Guild member Beverly Axelrod, a former white volunteer for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), was then Eldridge Cleaver’s fiancée and the first person he called for legal help. Eleven years his senior, the intense brunette from Brooklyn was a divorced mother of two teen-aged sons. She had made civil rights and social justice her life’s passion. A brilliant and gritty lawyer, she risked jail to register black voters for CORE in Louisiana in 1963. After she returned to San Francisco, she became the lead defense attorney in a lengthy 1964 criminal trial of protesters arrested for picketing employment discrimination by San Francisco’s Auto Row and Sheraton Palace Hotel.

Axelrod met Cleaver when he was still at Folsom Prison reaching out for legal assistance to win parole. While incarcerated, Cleaver had taught himself to read political books critically and to write on social issues. Influenced by the work of Malcolm X, Cleaver got the idea of marketing his own autobiographical essays from the publishing success of convicted rapist and long-time death row resident Caryl Chessman. Chessman was known as the Los Angeles “Red Light Bandit” for kidnapping at gunpoint couples stopped at traffic lights. Chessman became a cause célèbre for death penalty opponents during the dozen years he spent on death row, publishing four best sellers during the time before his execution in 1960.

Cleaver systematically wrote to lawyers listed in a professional directory offering the prospect of future royalties from the marketing of his own manuscript as legal fees for anyone who helped him to gain his freedom. Axelrod responded enthusiastically. She arranged to have parts of Cleaver’s manuscript and letters he had written to her critiqued by Pulitzer Prize–winning author Norman Mailer and then published in Ramparts magazine, a leftist literary periodical based in San Francisco.

Axelrod engineered Cleaver’s release from Folsom in December 1966. By then the confessed serial rapist had served nine years behind bars. Cleaver’s political essays gained him a national following and a job offer as a full-time staff writer for Ramparts. In the spring of 1967, Ramparts republished the essays as a book, Soul On Ice, which Cleaver dedicated to Beverly “with whom I share the ultimate of love.” Because of her relationship with Cleaver, Huey Newton had come to trust Axelrod as a close friend. She hosted many Panther gatherings at her San Francisco home. Newton posed in the wicker chair in Axelrod’s living room for the now-iconic photo used to adorn the new, ten-cent newsletter the Black Panthers began publishing in the spring of 1967.

When Cleaver contacted Axelrod with news of Newton’s arrest early on the morning of October 28, Axelrod knew there was no time to waste. She called her friend Charles Garry, a prominent leftist lawyer in his late fifties who specialized in defending murder cases. Axelrod had previously collaborated with Garry on Lawyers Guild cases. Both lawyers had long been on the FBI’s list of subversives. Coincidentally, Garry’s friend Dr. Carlton Goodlett, publisher of the African-American newspaper The San Francisco Sun Reporter, happened to be hosting that same week legendary black civil rights activist William Patterson. When Patterson heard of the shooting incident, he immediately asked to meet Huey Newton’s family.

Patterson was president of the American Communist Party and already had close ties to East Bay civil rights lawyer Bob Treuhaft and his wife Decca Mitford. Both were stalwarts of the “Old Left” — activists for social change in the 1930s and 1940s who also included rough-edged trial lawyer Charles “Charlie” Garry and his scholarly law partner Barney Dreyfus. At 76, Patterson was nearly a generation older than most of his Bay Area leftist colleagues; what was left of his receding hair had turned white. They had all met through Bay Area Communist Party educational programs in the ’40s. Since then, the Oakland firm of Treuhaft & Edises and the San Francisco firm of Garry, Dreyfus & McTernan had become the only two prominent white law firms in the Bay Area that represented black working class clientele. Patterson wanted to offer Huey Newton help from the American Communist Party. He had not seen a politically-charged case with such enormous potential for almost two decades. As a young lawyer he worked for International Labor Defense (ILD), the legal arm of the Communist Party, which placed Patterson on the appellate defense team for some of the most famous political prosecutions of the 20th century.

Patterson’s first opportunity involved the widely-publicized appeals in the mid-1920s following the death sentences of anarchist immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti on charges they participated in a bold 1920 payroll robbery-murder in the Boston suburb of South Braintree, Massachusetts. Upper-class judge Webster Thayer had both men caged during the trial. They were tried before a hand-picked jury that excluded any Italian-Americans, the most disfavored minority group in the area at that time. The judge openly ridiculed the defendants’ radical political views. The evidence of guilt was hotly-contested: the prosecution put on a number of eyewitnesses; the defense countered with numerous alibi witnesses. At the end, Judge Thayer instructed the jury to do its patriotic duty — indicating the pair deserved execution simply for dodging the draft during World War I, which had nothing to do with the charges against them.

Years of appeals followed, most of which came for hearing before the same biased judge. Hundreds of demonstrators came to the prison to protest their execution; Patterson was among more than 150 whom the police arrested. Sacco and Vanzetti were viewed in many countries as martyrs of the working class; their deaths triggered attacks on American embassies and other violent anti-American incidents around the globe. The heavy-handed behavior of the prosecutor and judge toward these two dissidents acquired its own derogatory name — “Thayerism.” It severely damaged the reputation of the United States’ justice system for many years to come. Growing political opposition to Thayerism also helped usher in major reforms. Patterson believed that, live or die, Huey Newton could ignite similar anger around the world, if enough people viewed his cause as a race and class fight for justice.

The opportunity to use the Newton defense to ask whether any black man could get a fair trial in America also reminded Patterson of the historic Scottsboro Boys’ appeals he worked on in the 1930s. Like Newton, the Scottsboro Boys faced the death penalty. In their case, it was based on false charges they gang-raped two prostitutes on a freight train passing through Alabama. The trials were about as unfair as one could imagine, which made them an ideal vehicle for holding American injustice up to international scorn. The original criminal complaint involved an inter-racial brawl that forced several white youths off the train. The white boys got the sheriff to deputize a posse to “capture every Negro on the train.”3 Some of those who had been in the fight had already fled the train by then. The deputies hauled off nine black teenagers aged 12 to 19 they found on board in five different cars, threw them all on a flatbed truck, and took them to the local jail where the terrified teenagers were held for assault with intent to commit murder.

The sheriff’s men also hauled in two young prostitutes whom they found in a different car from any of the boys. The older one, Victoria Price, was twenty-one and made up a gang rape charge to avoid prosecution for taking an under-aged girl across state lines in violation of the federal Mann Act.4 The claim quickly brought a lynch mob to the jail demanding the boys be turned over for hanging. The sheriff refused. Officials only dispersed the angry crowd by calling in the National Guard to protect the prisoners with machine guns and bayonets, accompanied by the promise of quick trials “to send them to the chair.”5

The trials became the star attraction at the Scottsboro County Fair. The boys were all from out of state, illiterate and not even permitted to contact their families. The nine of them had not all even met each other before they were arrested. Yet after being beaten, the first one tried swore he witnessed the others commit gang rape. That false testimony was supposed to spare his own life at the others’ expense — but the prosecutor asked for and got the death sentence for him anyway. In fact, there was no physical evidence that either of the young prostitutes had sex on the train in the time frame the gang rape was alleged to have happened. Represented by incompetent counsel, all but the youngest of the Scottsboro Boys were sentenced to die after back-to-back daylong trials before the same vengeful, all-white male jury. When the packed gallery heard the first boy’s death sentence, the spectators burst into applause. Outside, a band struck up, “There’ll be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight.”6 The trial of twelve-year-old Roy Wright was last. All but one juror voted for the death penalty even though, in view of his age, the prosecutor only asked for life imprisonment. The judge had to declare that one a mistrial.

As eight of the teenagers endured the miseries of death row, national newspapers reported the outrageous details of their prosecution that the ACLU had gathered post-trial. The Scottsboro Boys immediately became a cause célèbre for civil rights advocates. The Communist Party saw great recruiting potential in embarrassing the American system of justice as it had done through the martyrdom of Sacco and Vanzetti just four years before. The ILD quickly signed the boys up as clients, acing out the NAACP and America’s most famous defense lawyer, Clarence Darrow. Darrow felt the ILD lawyers “cared far less for the safety and well-being of those poor Negro boys than the exploitation of their own cause.”7 The legal battle turned into a test of endurance. Alabama prosecutors subjected the Scottsboro Boys to more retrials than in any other criminal proceeding in American history; hard-fought appeals and multiple trials saved their lives.

In the second trial in a different county, the ILD brought in a nationally known defense lawyer, New Yorker Samuel Leibowitz, a master of cross-examination reputed to nearly match Darrow in his prime. The younger prostitute changed her story and agreed to testify for the defense. The chief prosecutor was the son of the Alabama Supreme Court justice who had found nothing wrong with sending the Scottsboro Boys to the electric chair after the first mockery of a trial. Unhappy with all these interfering Northerners, the prosecution asked the all-white-male jury: “Is justice going to be bought and sold in Alabama with Jew money from New York?”8 The jurors quickly reached a guilty verdict and another death sentence. Yet in this case, Judge James Horton found the gang rape testimony of the prosecutor’s star witness simply not credible. He set aside the jury’s verdict only to lose his seat at the next election for his courageous action.

After the prosecutor got Judge Horton removed from the case, the newly-assigned judge refused to request state troops to protect the defendants, and Alabama’s governor declined to order any. Panicked, Liebowitz cabled President Franklin Roosevelt to urge federal intervention to prevent the “extremely grave” risk of a massacre.9 During the retrial, this judge showed open hostility to the Northern lawyers. Another all-white male jury convicted the defendants and sentenced all but one to die. More protests followed in Washington, D.C. and cities in the North. Ultimately none of the defendants was executed, and appeals of the Scottsboro Boys trials led to two hugely important Supreme Court decisions — the right of poor defendants to have competent counsel appointed in death penalty cases and the right of African-Americans to be included in the jury pool. Meanwhile, all of the defendants spent at least six years in traumatizing prison conditions with devastating effects on their lives.10

Three decades later, in the late 1960s, the right of black people to be in the jury pool in America still did not mean blacks got selected for criminal juries “of one’s peers.” Black defendants across the country still routinely faced conviction and execution at the hands of overwhelmingly white-male juries. The reason was that each side in a criminal case had — and still has — a certain number of discretionary “peremptory” challenges to eliminate qualified jurors. Historically, the vast majority of prosecutors used these peremptory challenges to systematically dismiss any blacks from their juries. With politically-motivated counsel to defend Huey Newton, Patterson sensed enormous potential for the charismatic black militant to draw attention to how the criminal justice system stacked the deck against black men accused of crime. Of course, unlike the Scottsboro Boys, the circumstances of this case made Newton’s innocence questionable. But that had been true of Sacco and Vanzetti as well. Their martyrdom worked better, from the Communists’ perspective, than if the pair had been spared execution. So had the infamous execution of Mississippian Willie McGee, charged with the unpardonable sin of raping a white woman.

Patterson had worked with Robert Treuhaft in the late 1940s on McGee’s highly politicized death-penalty appeal. Other leftist lawyers in the Civil Rights Congress participated, too, including future Congresswoman Bella Abzug in her first civil rights case. What they zeroed in on was Mississippi’s blatant double standard on rape prosecutions. The state had a history of executing black men for rape of white females, but not for white rapists convicted of ravaging white women. While white men got shorter sentences for raping white women, white men raped black women and young girls with little or no fear of any consequences. Other states in the Deep South had similar abysmal records.11

The charge that a black man had raped a white woman was guaranteed to make Southern white men’s blood boil. McGee barely escaped lynching as he awaited prosecution. In another egregious example of how black lives didn’t matter to the Southern justice system, his rape trial lasted only half a day. The alleged victim, 32-year-old housewife Willette Hawkins, claimed that the handsome, married truck driver crossed the tracks dividing blacks in Laurel from whites, broke into her home and raped her while threatening her baby at knife point. McGee did not testify in his own defense. The jury was all white men—blacks were theoretically permitted by law, but excluded in practice, and women were categorically banned from jury service by statute until 1968. (Mississippi was the last state to drop that prohibition.) The all-white-male jury deliberated less than five minutes before agreeing on McGee’s death sentence. On appeal, Civil Rights Congress lawyers won him a new trial in which the jury again voted for the death penalty. Due to more errors, McGee faced yet a third trial, which resulted in another all-white-male jury imposing the death penalty. Meanwhile, rumors around the black section of town were that McGee and Hawkins had been having an affair for a couple of years and got caught.

In that Cold War era, mainstream media considered Communist support for McGee’s appeal to the United States Supreme Court “the kiss of death.”12 The Supreme Court refused to touch the death penalty sentence. By then, famed Mississippi author William Faulkner and internationally renowned scientist Albert Einstein were among many prominent people who petitioned President Truman to pardon McGee or commute his sentence; Truman declined to act. Crowds gathered in New York City chanting “Jim Crow must go.” The day before his scheduled electrocution, McGee wrote to his wife: “Tell the people the real reason they are going to take my life is to keep the Negro down in the South. They can’t do this if you and the children keep on fighting.”13

The State of Mississippi played into the Communists’ agenda with its callous handling of the execution. State employees set up the traveling electric chair at the local courthouse; a thousand people came to celebrate Willie McGee’s execution. Two local Mississippi radio stations broadcasted it live so everyone outside could hear when 2,000 volts of electricity surged through McGee’s body.14 Black parents got the message loud and clear. They warned their sons: “Don’t mess with white girls. You see what happened to Willie McGee.”15

Bob Treuhaft’s work on McGee’s appeals helped earn him, in 1951, a place on Senator Joseph McCarthy’s short list of the most subversive lawyers in America. Treuhaft and his British wife, famed author Jessica Mitford, considered the distinction a badge of honor. The two joined Patterson and singer Paul Robeson in formally protesting America’s sorry record of racial injustice before the new United Nations in a lengthy petition they gave the incendiary title: “We Charge Genocide.” It included the fate of Willie McGee among its examples. The United States made sure the petition gained no traction, treating it as a gross exaggeration and effort to distract attention from the devastating atrocities committed by the Soviet Union. American mainstream media gave it little coverage. Patterson and Robeson soon had their passports revoked so they could not repeat their accusations in speeches overseas. Yet the charges reached a wide, receptive European audience and had broad dissemination in other parts of the world.

Patterson sensed that Newton’s trial presented a similar rare political opportunity to deeply embarrass the United States again in the eyes of a mostly nonwhite world for America’s continued mistreatment of racial minorities. Indeed, in the summer of 1968 the Panthers would present a new grievance petition to the United Nations, listing the denial in the Newton case of trial by a jury of true peers among its current examples of racism in the American criminal justice system.

Patterson knew just the lawyer he would like to see steer Newton’s case. First, Patterson had to convince Newton’s family. Wearing his customary suit and tie, the balding, bespectacled Communist was old enough to be Melvin Newton’s grandfather. Patterson talked Melvin and his sister Leola into meeting Charles Garry. Garry practiced in San Francisco with three partners and a couple of associates. Huey Newton’s two siblings came away quite impressed. Garry always dressed for success in the most fashionable suits. He greeted them warmly and assured them he had tried more than a score of capital cases and never lost one client to execution. But Garry expected the cost of the trial to reach $100,000, a staggering amount at the time. Melvin and Leola told Garry they did not have anything close to that kind of money, but they planned to establish a Huey Newton defense fund and Patterson had agreed to help obtain contributions. To the pair’s delight, Garry said he could wait. He also told them it would probably take three years to get Huey freed, assuming their best bet was only after an appeal. Melvin shared what he learned with David Hilliard, who liked what he heard: “We decided that Garry would be the lawyer because we wanted the very best. Huey’s life was at stake. . . . Left to the devices of the state he would have ended up dead in the gas chamber in San Quentin, because that’s where he was headed.”

Melvin took the responsibility of informing his parents and other siblings that he and his sister had found Huey a veteran death-penalty lawyer willing to start without them paying him a dime. Despite Beverly Axelrod’s strong endorsement of Charlie Garry, the Cleavers’ and Hilliard’s blessing and that of the Newton family, other Panthers were outraged. They lobbied for Huey to retain a black attorney. Meanwhile, Garry and Axelrod rushed to Newton’s bedside at Oakland’s Highland Hospital, where he had been transferred following surgery. On their first visit, on November 1, 1967, the two lawyers knew they would have to talk their way past the police to get access to their new client. They came dressed formally, as Garry always did, but Beverly Axelrod only did when in her work guise. When representing clients, she would put on a skirt suit and heels and push back her bangs in a hair band, her long hair folded into a loose bun overhanging the nape of her neck. But at home, the way Huey would have seen her with Eldridge Cleaver, she often wore a loose hippie dress and sandals with her long, brown hair dangling free. It left her unimpeded as she danced to rock music blaring on the record player.

Garry and Axelrod encountered a platoon of heavily armed police in the hospital corridors. They had to convince a hierarchy of belligerent officials to let them see Newton. When they arrived at their client’s room, he looked extremely vulnerable. An IV dangled from his arm; a tube remained in his nose. Under sedation since his arrival, Newton had lost a lot of blood, and appeared to be in great pain. Without asking any questions Garry felt right away that “this man was totally and completely innocent.” Beverly Axelrod’s presence was important. As Huey Newton’s trusted confidante, she introduced Charles Garry to him as someone he could also completely rely on. Knowing that his brother Melvin had vetted Garry, Newton was even more at ease. He painted a grim picture of his ordeal to the two white lawyers, recounting different police guards’ taunts: “Nigger, you are going to pay for this.” One officer threatened to cut off the tube “so you will choke to death, so that the state won’t have to bother trying you or gassing you.”16 Newton said he awoke once to see a shotgun pointed at his face and heard a policeman joke that they should get a razor to kill him with and say it was suicide.

Newton’s complaints alarmed Axelrod. She called a close friend from the Lawyers Guild, Alex Hoffmann, in Berkeley. Hoffmann, a slightly-built, Viennese-born lawyer, was four years Axelrod’s junior, with a brilliant legal mind and the same unbridled enthusiasm for radical causes as Axelrod. He looked like the product of the ’50s Beat Era that he was, a chain-smoking intellectual fond of jazz, his dark hair already receding. With Hoffmann in tow, Axelrod immediately set off to find Oakland Police Chief Charles Gain and demand that Newton be allowed nursing aides round-the-clock at his defense team’s expense. She and Garry had no doubt that the threats had occurred — the hatred the Oakland police felt for Newton was palpable. For the better part of a year, armed Panthers had been tailing officers around black neighborhoods, calling them “pigs” and challenging their authority.

The Panthers had first set foot on the world stage in May, less than six months earlier. Over twenty armed men (plus several unarmed friends along for support) marched into the State Assembly in Sacramento to assert their Second Amendment rights in opposition to pending gun control legislation. They also used that media platform to read a confrontational statement about their party’s opposition to the Vietnam War and racism in America. Shocked by the gun-toting visitors, the Assembly members passed a new “Panther Rider,” which specifically prohibited most civilians from openly carrying loaded weapons in any public place or street. That law made California the most restrictive state on gun control; it remains in effect today, in sharp contrast to permissive gun carry laws in many states where “Stand Your Ground” and “Open Carry” laws prevail.

During the next six months, Oakland police often invoked this new gun restriction when stopping Black Panthers with or without cause. The early morning shootout on October 28, 1967, marked the first exchange of gunfire. Now they had Newton in their custody facing potential execution for killing one of their own — the first Oakland officer shot in the line of duty in over twenty years. The police not only wanted revenge, they wanted to put an end to the growing popularity of the Panther Party platform. It addressed racial exploitation in fighting wars, in housing, education and employment. But the Panthers were best known for their angry and sometimes violent pushback against perceived police misconduct and racism in the criminal justice system. Impatient for results, the Panthers prepared an aggressive set of demands:

WHAT WE WANT NOW! . . .

7.WE WANT AN IMMEDIATE END TO POLICE BRUTALITY AND MURDER OF BLACK PEOPLE.

8.WE WANT FREEDOM FOR ALL BLACK MEN HELD IN FEDERAL, STATE, COUNTY, AND CITY PRISONS AND JAILS.

9.WE WANT ALL BLACK PEOPLE WHEN BROUGHT TO TRIAL TO BE TRIED IN COURT BY A JURY OF THEIR PEER GROUP OF PEOPLE FROM THEIR BLACK COMMUNITIES.

WHAT WE BELIEVE . . .

7.WE BELIEVE WE CAN END POLICE BRUTALITY IN OUR BLACK COMMUNITY BY ORGANIZING BLACK SELF DEFENSE GROUPS THAT ARE DEDICATED TO DEFENDING OUR BLACK COMMUNITY FROM RACIST POLICE OPPRESSION AND BRUTALITY.17

The police resented being viewed as a “white army of occupation”18 that the black community needed the Panthers to protect themselves against. Unbeknownst to the Oakland police at the time Frey confronted Newton, the Panthers numbered only about a dozen members, in and out of jail. Newton’s arrest and prosecution sparked what would become a dynamic expansion of the Panther Party. In November of 1967, a white hippie commune loaned Hilliard a psychedelic double-decker bus so the Panthers could drum up support in local neighborhoods to “Free Huey!” With a bullhorn, they repeatedly blasted the question: “Can a black man get a fair trial in America . . . defending his life against a white policeman?”19

Within a few months’ time, a new Panther chapter opened in Los Angeles. Even then, the two branches totaled about 75 people who identified themselves as Party members. The Oakland police would have been far more incensed had they seen what was coming; galvanized by the campaign challenging Newton’s imprisonment over the next year and a half, the Panther Party would burgeon to over 40 chapters, nearly 5,000 members, numerous community programs and a nationwide newspaper with a six-figure circulation. This rise was fast and precipitous. A year and a half after the Panthers’ spectacular Sacramento debut in the spring of 1967, J. Edgar Hoover listed the Party as the highest internal threat to national security of all black nationalist “hate groups.”

By the time they formed the Black Panther Party, Newton and Seale had developed a strong friendship based on a shared belief — the time had come for aggressive political action against entrenched racism. In his introduction to Rage, Professor Ekwueme Thelwell — then a recent advisor to the acclaimed civil rights TV series Eyes on the Prize — described Newton and Seale as combining the spiritual values of their hard-working, rural Southern parents in “uneasy tension with another incompatible current: the in-yo-face, up-against-the-wall-motherfuckah, quasi-criminality and macho violence of the urban street-gang culture.”20 The deliberately calculated “in-yo-face” strategy of young armed blacks looking “boldly into the eyes of white authority” took the breath away from observers on both sides of the racial divide. Newton and Seale were determined to lead by example “above ground,” ostentatiously waging “ideological and material battle in plain view.”21 They quickly became known as “the baddest niggas on the scene,”22 a reputation that new recruits found irresistible.

Reprinted courtesy of The San Francisco Sun Reporter.

Front page of the San Francisco Sun Reporter, October 1, 1966 featuring the riots that followed the killing of unarmed sixteen-year-old Matthew Johnson in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco by a local policeman on September 27, 1966. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland within weeks of this incendiary incident.