Читать книгу AMERICAN JUSTICE ON TRIAL - Lise Pearlman - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

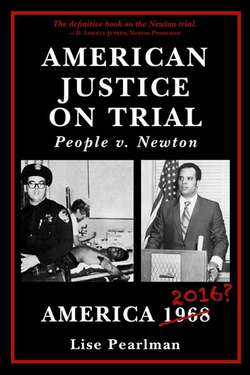

5. THE DEFENSE TEAM

ОглавлениеTHE ONLY CLIENTS OF MINE THAT GO TO SAN QUENTIN ARE THE ONES WHO LIE TO ME.

— SIGN ON CHARLES GARRY’S DESK

Everything about the Newton case would be unusual, starting with the first hearing. Charles Garry walked with determination as he made his way back to Huey Newton’s Highland Hospital room through the heavily-guarded corridor. At 58 and balding, he was still trim and muscular. Garry came smartly dressed as always in a fashionable suit and tie. Because of Newton’s condition, the court had ordered a special bedside hearing to announce the formal criminal charges. Lanky prosecutor Lowell Jensen was just 39, nearly twenty years Garry’s junior. Jensen had enough experience trying violent felonies that he took this case in stride. Yet the Newton trial would be Jensen’s first exposure to trying a case against Garry, whom Jensen knew mostly by reputation as a formidable criminal defense lawyer favored by radicals. By the time they met, Jensen was also already scheduled to try the Oakland Seven against Charles Garry, which was expected to take place shortly after the Newton trial ended.

They stood near the bed as the court reporter made the record. It did not take long for Municipal Court Judge Stafford Buckley to formally transfer Newton to county custody on charges of murder, assault with a deadly weapon, and kidnapping. This was too early for Newton to have to enter a plea, but it was the first step toward his possible execution — and it was over in minutes.

Following the arraignment, sheriff’s deputies took over guard duty from the Oakland police. Newton was now a county prisoner. Still fearing for Newton’s life, Garry asked Judge Buckley to order that Newton not be moved, a request the judge took under submission. Meanwhile, at a Catholic church not far away, the slain young policeman, John Frey, who had only served on the force for a year and a half, received the special treatment reserved for fallen heroes. His funeral included a twelve-man honor guard, a long procession of private cars and a squad of motorcycles, with over 150 colleagues participating. Officers’ wives showed up for the emotional funeral service as well, each acutely aware it could have been her own spouse’s funeral they were attending.

All the officers in attendance likely thought as Commander George Hart did: “There but for the grace of God.” It was the first policeman’s funeral Hart had attended since he joined the force in 1956. He would endure ten more during the remainder of his tenure in the OPD — each a gut-wrenching experience. “It rings real close to home.” Honorary pallbearers at Officer Frey’s funeral included Police Chief Charles Gain, County Sheriff Frank Madigan, the city manager, a Superior Court judge, a Municipal Court judge and Assemblyman Don Mulford from Piedmont, author of “the Panther bill.” The Oakland Tribune gave the funeral extensive coverage.

The situation looked grim for Newton. Garry later described the case as “the most complex, emotional, fascinating case I’ve ever tried . . . Huey was the kind of person I immediately felt a warmth and friendship with; his charisma and his openness and frankness just came right through, even while he was lying in a hospital bed with a tube through his nose.”1 Garry was married, with a mistress as well, but no children. This self-described streetfighter in the courtroom related to Huey as the son he never had.

Unlike Oaklanders who had been following the emergence of the combative Panther Party over the past year, when Charles Garry first agreed to represent Huey Newton, Garry knew virtually nothing about the Panther Party. After he obtained Newton’s rap sheet, he viewed Huey as a scrappy warrior like Garry himself was. Garry believed that the job of the “Movement” lawyer was to expose the system as rotten, and “tie it up.”2 The only clients Charles Garry could never imagine defending were Nazis or fascists. His empathy for Newton was reinforced by reading the revolutionary literature Newton assigned him as homework: if one viewed the black community as a colony oppressed by its mother country, then crimes like those Newton was charged with were either self-defense or self-liberation.

Garry instantly realized that any chance of winning the case required him to orchestrate two high-powered defense strategies: one, a traditional defense relying heavily on research and writing assistance; two, and more importantly, a political defense of the Panthers as peacekeepers protecting their community from police oppression. As Garry planned his public relations campaign, he knew the audience he really needed to convince was an as-yet unpicked panel of jurors, likely unfamiliar with life in black ghettos. In the crucial jury selection process, he would need help from experts as well as top-notch support staff. The best person to ask was right there in his office.

Now thirty-five years old, Guild lawyer Fay Stender had been a part-time associate at Garry’s firm since 1961. Working for clients she believed in put the five-foot-eight, dark-haired Jew in an enviable position — few established local firms then hired any women lawyers, or Jews for that matter. Stender was the only woman lawyer ever hired by the firm. Women were considered especially unsuited for criminal trial practice, especially among old war horses like Charles Garry. Yet, after six years, Stender had become Garry’s right hand for legal research and briefing. The son of immigrant Armenians fleeing Turkish massacres had never fully mastered English syntax and had little interest in paperwork.

For Garry — unlike his far more genteel partners — it was not unusual to instruct his secretary to “get that motherfucker in here to pay his child support.” Uniquely structured phrases became “Garryisms” fondly repeated in the office.3 Recently, in light of landmark Supreme Court rulings, court practice had evolved. Defendants now had more procedural rights. Instead of the shoot-from-the-hip style Garry was used to at trial, defense lawyers were starting to file strategic pretrial motions ahead of time to preclude the prosecutor from calling challenged witnesses to the stand in front of the jury or to prevent the admission at trial of improper testimony or illegally obtained evidence. If Stender’s sexist mentor had had his way, the former Supreme Court clerk would have stayed his assistant for her entire career.

With her two children now both in elementary school, Stender had just begun working full time. When she started at the Garry firm in 1961, she had much preferred library research and writing that she could do on a flexible schedule. At the time, Stender was recently separated from her husband Marvin, and needed to race back from San Francisco each work day to relieve the patchwork of babysitters she had cobbled together for her toddler daughter and three-year-old son. By the late fall of 1967, the Stenders had been reunited for the better part of three years. Fay Stender was eager to take on new challenges at work to prove she was partnership material.

Though she had little criminal trial experience, Stender had honed her knowledge of the law by assisting Garry’s highly demanding partner Barney Dreyfus on several death penalty appeals. Garry considered Stender’s skills essential to this difficult defense. He popped his head into her tiny cubicle as the dowdily dressed lawyer pounded away on her typewriter. Stender typed faster than any secretary in the office and prepared all her own filings. When Garry asked Stender to join him when he made his next visit to Newton, she instantly realized this might be the career break she was looking for.

Stender had some background handling civil rights cases and had even spent a week in Mississippi during the 1964 Freedom Summer, but by 1967 had made her niche representing draft dodgers. Over time, she had grown disenchanted. “I knew for every one I handled [for a white, middle-class male], there were many Third World people who really needed a lawyer and couldn’t get one.”4 Here was Charles Garry offering her the type of satisfying challenge she much preferred. Instead of yet another white middle class draft dodger, Stender would be right at the center of the hottest Movement case around, with the client’s very life dependent on their efforts.

Like everyone else, Stender had heard about the Panthers’ bold appearance in the Assembly months earlier. She had also met Eldridge Cleaver when he came with Beverly Axelrod to the book release party for Soul On Ice in the spring of 1967. Stender had joined in a toast to their engagement. Like Axelrod, Stender was passionate about social justice. She had worked together with her husband, Axelrod, and other local leftist lawyers a couple of years back in a group they called the Council for Justice. As volunteers, they took on anti-war clients and politicized cases for Cesar Chavez and the farmworkers until the group folded for lack of funding. Whatever Garry needed her to do, Stender was game.

By the fall of 1967, though the police viewed the Panthers as thugs, they were beginning to appreciate that the Party was unlike any street gang they had previously encountered. It unnerved them to see pig graffiti on the walls of West Oakland with messages of “off the pigs” scrawled alongside. The defense soon found out that the OPD began furnishing patrol cars with a list of known Panther vehicles to stop on any pretext. Anyone who lived in East or West Oakland could see deadly conflict ahead.

One of those people was teenager Leo Dorado. Back in the days before it ever crossed his mind he might become an Alameda County prosecutor let alone a pioneering Latino judge, Dorado starred in basketball and baseball games played all over the city. He made it a point to know where trouble might lie. The tall Mexican-American had his eyes fixed on getting into Cal and not getting mugged or arrested first for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. That had happened to too many of his friends. So, when Dorado first heard of this new, armed, black gang following police around in West Oakland, he paid attention. When news hit that the Black Panthers had shown up armed at the State Capitol, Dorado thought it could only mean they were bent on becoming martyrs.

That fall at Cal reinforced Dorado’s assumption: “We heard a lot about how . . . extremely militant they were. . . . The general feeling was they weren’t going to last very long because they were going to step over lines . . . Oakland police . . . were a very, very strong police department, and they would meet force with force. . . . all the force and violence they needed to put them down. . . . If it was a matter of them getting hurt and injured and killed, then that was going to happen . . . they would get killed.” When word spread of the October 28, 1967, shootout, Dorado assumed that Newton had just stepped forward as the first martyr. There was no question in Dorado’s mind — or the mind of anyone he knew — that Newton would get the death penalty.

Charles Garry had the opposite reaction — not if there was anything he could do about it. He could not wait to have an opportunity to speak to his new client alone in the hospital. The veteran trial lawyer’s first advice to Huey as he lay recovering from surgery was what Garry told all of his clients: “Make no statements to anyone.” Garry had to make sure Newton did not blow whatever chance he had of avoiding the gas chamber by bragging about offing a pig to his friends or saying anything at all about the incident that could come back to haunt him at trial. Newton’s chances of success were low enough already. Even a good friend or relative, not to mention a cellmate, might be forced to reveal anything Newton said about the case.

After Garry came back from visiting his brother, Melvin Newton asked Garry, “Did he do it?” Garry said he never asked. Melvin also decided against asking his brother to tell him what happened on Seventh Street that morning — there wasn’t much Melvin could do with the knowledge one way or the other. In his short acquaintance with the Panther Party, Melvin had already learned not to ask questions that would lead to answers he could do nothing about.

Like Charles Garry, many criminal defense lawyers don’t want their client’s story. The defendant has a right not to testify on his own behalf and knowing what he has to say could limit the array of defenses. In fact, Garry did not seek any information from his client about the shootout until a few days before Newton took the witness stand in the middle of the trial. When asked why not, Garry later explained, “I wasn’t particularly interested.”5 Garry’s primary aim matched that of Huey Newton himself — to conduct a political defense, painting a picture of a racist establishment that itself should be on trial. The Panthers reminded Garry of some of his most militant union clients decades before, whom he felt had been even more vilified by society. Garry saw in the Panthers “a kind of cohesion of all the things that the labor movement originally started out in the ’30s fighting for.”6

The timing of the breaking story was excellent for gaining leftist political support. The Bolivian army captured legendary guerrilla leader Che Guevara in early October 1967 and executed him just a few weeks before Newton’s arrest. Only a few months before, Berkeley’s community-supported station KPFA broadcasted a daring live interview with Che in South America. Radicals like KPFA station manager Elsa Knight Thompson rushed to champion the cause of Huey Newton as a revolutionary like their martyred hero Che.

Though Garry would immediately proclaim his client’s innocence to the press, the prospects of Newton’s acquittal at that point looked slim to non-existent. When Newton’s arrest for murder hit the front pages of local papers, two totally unrelated police shootout cases were set for trial the following week. Having three local cases involving police shootings in the news at one time was extraordinary. But Newton’s case drew by far the most coverage. The attorneys in both of the other cases told the judge that they needed a delay of their clients’ trials in light of the mounting hostility in the community over Officer Frey’s death. Otherwise, the lawyers expected the jury box would fill with folks ready to throw the book at anyone accused of killing a cop. Although judges generally frown on delaying trials already set, the delays were granted. This underscored what Charles Garry already knew — shooting a police officer is a crime that packs an oversized emotional impact on the entire community. Suddenly everyone feels less safe.

Garry needed to counteract the negative publicity as quickly as possible. He pounced on an opportunity that just got handed to him: a local physician contacted Garry after seeing the newspaper photo of Newton handcuffed to his gurney before surgery. She was flabbergasted that doctors at Kaiser Hospital would allow police to stretch out the arms of a man with a serious abdominal wound. Garry asked Stender to quickly draft a complaint charging Kaiser with medical malpractice. Meanwhile, they obtained the original uncropped photo of Newton on the gurney showing the startled police officer in the foreground. They used that photo on the cover of a new pamphlet their new white allies put together for wide distribution, accompanied by the caption, “Can a black man get a fair trial?”

The lawyers’ stated aim was to get Newton the impartial jury of his peers promised in the Bill of Rights, but never delivered to minorities in practice. The defense brochure also focused on a fair trial. Yet the “Free Huey” chant adopted as the Panthers’ mantra at pretrial hearings focused instead on rousing support for his release regardless of the evidence. Most of Newton’s militant associates assumed he did what he was accused of. The Panthers considered Newton amply justified in killing an oppressor and wanted their leader out of jail by any means available. Many radicals thought Newton had just started the revolution. As Cleaver later wrote: “We all knew that it was coming. When, where, how — all had now been answered. The Black Panther Party had at last drawn blood, spilled its own and shed that of the pigs! We counted history from Huey’s night of truth.”7

A front page editorial in The Black Panther newspaper appeared with a half-page headline “HUEY MUST BE SET FREE!” The article placed the shooting squarely in the context of historic race relations, emphasizing that it occurred in a black ghetto between a black resident and white cops who lived in the white suburbs:

On the night that the shooting occurred, there were 400 years of oppression of black people by white people focused and manifested in the incident. We are at the cross roads in history where black people are determined to bring down the final curtain on the drama of their struggle to free themselves from the boot of the white man that is on their collective neck. . . . Through murder, brutality, and the terror of their image, the police of America have kept black people intimidated, locked in a mortal fear, and paralyzed their bid for freedom. [Newton] knew that the power of the police over black people has to be broken if we are to be liberated from our bondage. These Gestapo dogs are not holy, they are not angels, and there is no more mystery surrounding them. They are brutal beasts who have been gunning down black people and getting away with it. . . . Black people all over America and around the world . . . are glad for once to have a dead cop and a live Huey . . . we want Huey to stay alive . . . we want Huey set free.8

Belva Davis was sure that someone with Huey Newton’s reputation could not shoot an Oakland police officer and expect to get off. “Everyone thought that surely he would be convicted of first-degree murder.” Just a little over six months earlier the media had covered the first execution on Governor Reagan’s watch after Reagan had handily won office as a strong believer in the death penalty. An African-American man named Aaron Mitchell was on death row when Reagan was sworn in, convicted of killing a white policeman in a shootout after Mitchell attempted to rob a Sacramento bar in January 1963. Interviewed the day of his execution on April 12, 1967, the condemned man told reporters: “Every Negro ever convicted of killing a police officer has died in that gas chamber. So what chance did I have?”9 Belva Davis thought Newton had no prayer of a different result.

Davis now faced her own dilemma. Here was “the mild-mannered, piano-playing, opera-loving Newton that I had met” likely headed to the gas chamber. The CBS affiliate where she worked in San Francisco had been the first station to bring on two African-American newscasters. She and Ben Williams talked about who would likely be assigned to cover this story. He was a much more seasoned reporter. She asked him to please volunteer: “This is not a good way to begin a career.” Ben got the assignment to cover the trial and Belva Davis became his relief person.

The defense had already made a formal motion to Municipal Court Judge Buckley to order that Newton stay at Highland Hospital under armed guard, which his family would foot the bill for. They argued it was the only way to keep Newton safe. Judge Buckley had not yet ruled on that motion when the county transferred Newton to a cell on death row at San Quentin Prison. Similar transfers had occurred with a half-dozen or more other prisoners charged with serious felonies earlier that year as a cost-saving way for the county to ensure greater security.

Melvin Newton and his father visited Huey at San Quentin, extremely distressed that he was already on death row. His mother was too upset to come. It surprised them to discover that Huey was actually relieved to be left in isolation to recover peacefully from his surgery. But he told them that, whenever he was taken from his cell, a guard would lead the way to announce “Dead man walking” and another guard would follow behind him. Huey had been taken aback, but soon learned this was the protocol for every prisoner on death row. His family found it shocking — months before any trial, the justice system was treating Huey as if he were simply awaiting execution. The defense team vigorously objected to him being left there until trial. A few weeks later, the sheriff transferred Newton to a jail cell in the courthouse on the shores of Lake Merritt.

To bring Newton to trial, the prosecutor had alternative paths he could pursue: convening a grand jury or conducting a preliminary hearing in municipal court. A preliminary hearing would entitle Newton’s counsel to cross-examine the prosecutor’s witnesses in open court. In contrast, appearances before the grand jury were confidential. The defendant could not have counsel present. Grand juries were (and are) notorious for doing the prosecutor’s bidding — they only hear one version of events. Not surprisingly, Lowell Jensen took the case to the grand jury. It had the added benefit of avoiding a media circus. Ten years later, the California Supreme Court ruled that choosing a grand jury provided the prosecutor with such a tactical advantage that defendants should have the right to ask for a preliminary hearing after an indictment is issued. In 1990, prosecutors went to the voters and won a change in the Constitution, taking that right away.