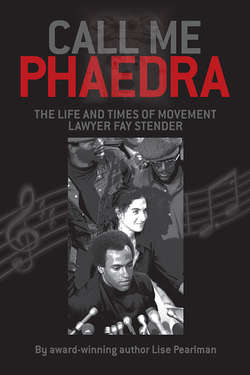

Читать книгу CALL ME PHAEDRA - Lise Pearlman - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление∎ 2 ∎

Predestination or Free Will

“The freedom totally dominated me.” 1

— FAY STENDER LOOKING BACK IN 1972 AT HER COLLEGE DAYS

When the day finally came for Fay to depart for college, Sam, Ruby and Lisie accompanied her to the train station. Fay looked elegant, wearing a new mauve suit with matching stockings and pumps — a seventeen-year-old with a ticket to an exciting new world. Lisie also felt the importance of the occasion. She looked forward to being an only child and to the peace that would settle on the household when Fay left. Ruby and Sam had strong misgivings. Cal provided an inexpensive, first-rate education right there in Berkeley. Ruby particularly wanted to have her melancholy older daughter close at hand. She had not given up hope of guiding Fay to a career as a pianist.

Cal was also the first choice of the in-crowd at Berkeley High. Fay told her close friends that it took screaming and crying to get her parents to accede to her wish to go to Reed College in Portland, Oregon — the same prestigious private school that her friend Hilde had chosen. Tuition was several hundred dollars per year, about ten times the cost of Cal. Surprisingly, Fay had not confided her ambition to Hilde. Possibly, Fay feared losing the battle with her parents, who made Fay first attend a summer session at Berkeley, before acquiescing in her choice.

By 1949, when Fay applied, Reed had a national reputation as a left-leaning haven for intellectuals, individualists and iconoclastic fine arts majors not wanting to pursue the beaten path. Reed was the West Coast answer to Swarthmore College in the East. Most locals did not hold the college in high regard; they considered it too liberal. About half of the 500 or so students at the college were women. There were virtually no minorities and no poor people.

Fay loved the college’s focus on intellectualism. Her first assignment in introductory humanities focused on the ancient Greeks. The teenager eagerly absorbed her instructor’s weighty pronouncement that the study of classical Athenians’ politics, philosophy, literature, law, science, history and art would reveal the holiest, most glorious and sacred secrets of Western civilization. She especially found fascinating the topics of predestination and free will.

It did not occur to Fay, at seventeen, to incorporate her knowledge of ancient Jewish history from confirmation classes with what she learned in college. She had never experienced any external validation of Hebrew school teachings — that the legacy of kings David and Solomon predated the golden age of Pericles by half a millennium. Only when Fay reached her late forties did she reflect that her Reed professors never mentioned any influence on Western civilization from the earlier advanced Jewish kingdoms; nor did they acknowledge that the Greeks appropriated many of their successful ideas from other advanced Near Eastern cultures.

What mattered most at seventeen was the freedom from parental control. Fay later said that upon her arrival at the Reed campus, “The freedom totally dominated me.”2 As a first test of her independence, she introduced herself to new friends by the shortened surname of Abrams, which sounded the same as it had always been pronounced. Reed had rules by which it sought to operate in loco parentis. The girls’ dorms only allowed male visitors from one to three p.m. on Saturdays and Sundays, provided the room door remained open six inches and three feet were on the floor at all times. The dorms were locked at ten p.m. on weekdays and twelve p.m. on weekends, with a procedure for signing in and out. Boys easily evaded those rules by climbing in and out of dorm windows, and girls signed out to stay off campus unsupervised for entire weekends.

“The freedom totally dominated me.”

Reed College Campus

Source: Reed College Website, 153700-004-18905E12Reed.jpg-Photos

Rob Scott

Source of headshots from 1949 Olla Podrida: Berkeley Public Library, https://archive.org/details/ollapodridaunse_40

Rob Scott, Fay’s first boyfriend at Reed, graduated from Berkeley High in the fall of 1948, six months before Fay. At Reed, Rob’s roommate nicknamed her “Twinkletoes” when she gave Rob dancing lessons. Fay often played classical music on the piano in a dormitory living room. She joked to Rob that she might end up playing tunes in a bar somewhere. Her prediction almost came true.

Fay’s first boyfriend at Reed, Rob Scott, also graduated from Berkeley High. The two had first met on the eve of attending college. Fay and Rob spent many afternoons the fall of their freshmen year in the living room at Anna Mann, a dormitory furnished with a piano. Fay tried to teach Rob the Charleston, earning her the nickname “Twinkletoes” from his roommate George. More often, Fay played classical music from memory while Rob sat nearby, reading from a set of the collected works of Jules Verne. Rob asked her once how many compositions a concert pianist needed to know by heart. Fay replied with an impressive list he found hard to believe. Yet it did not even include the many popular tunes she had memorized from the radio. She joked that she might instead end up playing the big band song “Deep Purple” in a bar somewhere — a prediction that almost came true.

* * *

Fay’s time at Reed coincided with a new, frightening era, the unleashing of the atom bomb and the Cold War against Communism. She was in her second semester when the FBI arrested Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for conspiracy to commit espionage by providing the Russians with top-secret information on nuclear weapons. Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy then startled the nation in February of 1950 with claims that Communists had infiltrated the State Department, fueling a mounting national atmosphere of anti-Communist hysteria. Fay and her friends began to question government policies they had never before doubted, worrying about the dangers of nuclear weapons and radioactivity. Still, there was little political activism in those days. The only major urban issue Reed students tackled in Fay’s freshman year was a “Fair Rose” campaign to abolish discriminatory housing practices in the Rose District of Portland. It paralleled a “Fair Bear” campaign the same year at Cal.

During Fay’s freshman year, her parents moved to Pennsylvania where Sam Abrahams had been offered a promising job in the asbestos industry. Lisie, then a high school sophomore, was desperately unhappy about the change. Fay flew East that summer to join her family. Shortly after she arrived, Communist North Korea launched an invasion across the 38th parallel. This time when the United States became embroiled in war, Sam remained uninvolved, saddled back East with three unhappy women. Lisie and Ruby pined for California as Fay yearned to return to the freedom of Reed.

When Fay went back to Portland that fall, she continued dating Rob Scott, immersed herself in comparative literature courses and enjoyed ballroom, folk and square dancing — not politics yet. She joined the college’s music program and performed a solo concert. She also entertained friends on occasion. One of the gathering places for students was a student-owned and operated coffee shop on campus. In the fall of 1950, the coffee shop hired a transfer student named Bob Richter as a part-time cashier. He quickly became a celebrity in Fay’s small world.

Bob Richter was a rare conscientious objector to the prewar peacetime draft of 1948. He had been convicted while attending junior college in Los Angeles; his service of the three-year prison sentence for refusing to register for the draft was delayed pending appeal. Chances of reversal were slim. Conscientious objector status was then limited to Quakers and others whose religious beliefs conflicted with military service. Bob’s opposition was personal; his parents were nonobservant Jews who had raised him as an atheist. In fact, his mother was a Communist who had been a teen-aged nurse in the Russian Revolution and considered religion the opiate of the masses.

As a last resort, Richter’s attorneys sought review in the United States Supreme Court while Bob went back to visit his family in New York over the 1950 winter break. On Christmas Eve, Bob stood in the long line for the midnight mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue and spotted Fay with a companion in the same queue. They exchanged pleasantries. Soon they ran into each other again heading back to Reed on the same $99 super-discount flight.

Fay and Bob began talking as they boarded the plane to Oregon and found each other fascinating company through its many landings and takeoffs. Fay particularly enjoyed Bob’s attention because she had just been rebuffed by a new love interest. Bob confided that if the Supreme Court petition for review was unsuccessful, he likely faced prison time. Fay endeared herself to Bob even more when she fell asleep leaning against him. Then a passenger died en route to Portland and the pilot made an eleventh, unplanned, stop in Montana to unload the body. During the delay, the stewardesses herded the remaining passengers into a small wooden building that served as the Great Falls airport. Bob and Fay listened to the jukebox play the “Tennessee Waltz” over and over again, wondering whether it was broken or someone else there just really loved that song. By the time they arrived at Reed they were inseparable.

Source: Bob Richter

Bob Richter, Fay’s first fiancé, at age 21 in 1950 when he transferred to Reed College. In early 1951, he was jailed for refusing the draft as a would-be conscientious objector. The conviction was later expunged. Bob went on to an extraordinary, award-winning career as a documentarian. (www.richterproductions.com.)

In January of 1951, Bob Richter learned two pieces of bitter news: he lost his final appeal and the military rejected his offer to volunteer only as a medical noncombatant. His friends at Reed threw a farewell party for him at the end of the month. By then, he and Fay had made impetuous plans to marry after he returned from his prison term. After the bittersweet festivities and emotional parting from Fay, Bob hitchhiked to Los Angeles and turned himself in. The prosecutor sympathized with Bob’s plight but felt she had no choice: the law was the law. She cried and kissed him on the cheek as she oversaw Bob’s delivery to the county sheriff’s deputies.

Meanwhile, Fay continued to frequent the student coffee shop and to relay Bob’s travails to his former co-workers. He spent a brief time in poorly maintained Los Angeles and Maricopa County jails before reaching his final destination, a minimum security prison in Tucson, Arizona. There he would serve out his sentence with a dozen other conscientious objectors in an open barracks filled with illegal immigrants from Mexico, income tax evaders, a white murderer and a Navaho jailed for a violent felony.

Because of Bob’s college education, the warden had originally assigned him to office duties. Bob complained about such preferential treatment in a letter to Fay. He had warned Fay that all his incoming mail was opened and stamped before he saw it. He learned the hard way that the warden read his outgoing mail, too. Bob spent the next several months on a logging crew paving roads for a former German prisoner-of-war camp. The camp had been newly renovated to house up to 100,000 Communists and subversives the FBI then expected to designate as too dangerous to remain at large in society. Bob assumed his own mother was among the potential internees.

Though Fay still socialized on occasion with Rob Scott, she knew she was Bob Richter’s lifeline. She wrote him long letters twice a week entertaining him with her activities. That included an excursion with friends to a popular Negro night club in Portland, for Fay a novel and exhilarating experience. During spring break, Fay traveled 25 hours by bus from Portland to see her fiancé. The American Friends Service offered a place for her to stay near the Tucson prison. Visits with Bob would be supervised as they sat on chairs too far apart to touch each other, but close enough to whisper and recover a sense of intimacy.

At 19, Fay felt she was becoming a mature woman of the world. As her sister’s sixteenth birthday approached, Fay shared her insights with Lisie in a lengthy heart-to-heart message beautifully printed by hand in two colors. Fay felt she was wandering in a maze, getting lost and then finding her way again. She told Lisie: “The real meaning of life is in three things, love, beauty and pain. And these three are all really one which is God or Truth. And you will only come to know and understand this by giving, and giving too much.”3 Lisie treasured the unexpected birthday letter from Fay, hid it in her drawer and kept it with her throughout her life.

Fay had already made plans for the summer that upset her parents as much or more than learning about Fay visiting her boyfriend in prison. Bob had previously worked at the local office of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC). It advertised at Reed a Student Peace Service Program in Mexico in the summer of 1951 to inoculate villagers against typhoid. Fay felt compelled to go — to do something useful rather than sit on the sidelines. She asked her parents to pay for that trip and secretly planned to visit Bob in Arizona on the way down to Mexico and back. The Abrahams refused. Undaunted, Fay talked an older cousin who was a lawyer into providing her with the money she needed. Another volunteer from Reed agreed to detour through Arizona so Fay could visit Bob first.

Her parents were stunned at their reckless daughter. Yet over the summer Fay corresponded with her parents and got their reluctant acceptance of her choices. Most appealing to them was her decision to leave Reed and go to Cal that fall. She had become quite depressed that spring at Reed, as well as broke. At Cal, her finances would not be so stretched. Though she worked hard to repair her relationship with her parents, Fay feared from past experience that she would precipitate another rift somehow before too long.

The experience in Mexico that July and August marked a turning point for Fay. She exulted in becoming the best among the volunteers at giving shots and enjoyed learning enough Spanish to carry on meaningful conversations. She even took her turn cooking. Being paired with another volunteer helped her avoid anticipated fiascoes due to lack of kitchen skills. The villagers’ joy in simple pleasures impressed her, but their living conditions and poor health were appalling. Fay even considered quitting school to remain working in Mexico with toddlers whose lives could be easily improved. What struck her most was the villagers’ tolerance of invasive insects, not even batting an eyelash when flies flew in front of their faces.

Yet, most of all, Fay gained insights into herself. Once she transferred to Cal and earned her degree, she was considering graduate school in sociology. She also wanted to resume piano lessons. While in Mexico, she had heard the Emperor Concerto on the radio and yearned to reconnect with her former piano teacher. She wanted an opportunity to play the concerto as she felt it should be played, improving on her debut at the San Francisco Symphony as a young teen. Ruby would be delighted.

More troublingly, Fay had been feeling dishonest in all her cheery messages to Bob. He was hoping to win parole after one year in jail, and they talked about marrying on her next birthday. For some time she had harbored serious doubts about their future together. Fay revealed to Bob her history of alternating between wildly conflicting urges that could doom their relationship. She gave him a recent example. When Fay started working for AFSC in Portland, she had deliberately acted like a quiet, religious girl. Fay dutifully held hands before meals in silent prayer and shared weekly news from Bob in prison to reinforce acceptance into their circle. Most of all, she wanted the Quakers’ social pressure to keep herself on that virtuous path. But on arrival in Mexico, Fay veered in a different direction. She joined their mutual friend Steve from Reed every night, going out drinking until the wee hours, shocking all of their AFSC campmates and feeling no shame.

Fay came to the realization she had never made decisions, but acted on uncontrollable impulses, lurching from one course to the next. She believed in predestination, not free will. She wondered aloud to Bob: “At what freakish moment will this force contort or twist my mind into doing what? It’s terrible…. I’m left with a feeling of being on a pattern, a track that I have to go on but I don’t know where it is going…. I am powerless to alter it or find out where it goes.”4

On the way back from Mexico, during the third week of August 1951, Fay and Steve took several buses that connected ultimately to Tucson, a trek that left her quite ill. After visiting Bob again, Fay could not hide her unhappiness at the disparate treatment she observed in the prison camp. It bothered her that Bob had gained weight after he was reassigned to library work. Why did he and other conscientious objectors who shirked deadly combat in Korea all have easier work assignments than the Mexican “wetbacks,” as Bob and the others referred to them? Though Fay had been touched when Bob whispered at their visit, “You know I’m crazy about you,” she openly voiced misgivings about their marriage plans. Fay was grateful when Bob wrote back that they needed to know each other better. She wondered whether love was the deciding factor. “What do I actually want? Is it security?”5 That question would trouble her to her dying day.

Fay’s parents still lived in Pennsylvania, but her mother flew to the Bay Area that August to visit family. Somewhat to her surprise, on reuniting with Ruby, Fay enjoyed being pampered with new clothes, a comfortable hotel room and luncheons at high class restaurants. The contrast with life among the Mexican villagers unsettled her. Fay had brought back silver earrings as souvenirs, which she distributed among friends and family as she shared stories of her summer experience with the Quakers, hoping to convince them of the program’s merit. She and her mother got along remarkably well on this visit, a welcome change.

Despite her growing ambivalence toward a future with Bob, Fay arranged for another trip to Tucson from Berkeley in mid-September. She asked Bob’s parents to pay her way, $35 that Fay could not herself afford. Fay even arranged for a special treat. She knew that the prison had a piano. Although the barracks were off limits to visitors, an exception had been made for officials of the local evangelical church, which conducted regular Sunday services there. Fay asked the prison staff in advance if she could play the piano for the inmates. The unusual request from an attractive college coed persuaded the warden, who agreed to let her play on an upcoming Saturday afternoon.

When Fay arrived on September 15th, the warden unlocked the barracks’ door and escorted Fay in. She mesmerized the inmates with her recital. Most had never heard any classical music before. After Fay left, Bob’s standing among the inmates rose considerably. Her performance remained a topic of conversation for many months. Looking back, Bob likes to think that Fay’s visits to him at Tucson and her small success in humanizing that bleak environment inspired her later pioneering prison work.

Fay could not resist sharing with her family the details of her prison piano performance. She also shocked them with a new announcement. Shortly after enrolling at Cal, she changed her mind and secretly reapplied to Reed in early September. She had just been accepted back at Reed and made plans to live off campus in Portland with a girlfriend. Even earning some money giving piano lessons, she could ill afford Reed’s tuition. When she told her parents they exploded in anger, but Fay was not to be dissuaded.

Fay never dared tell her parents what happened next. Back in the spring she had become intrigued by a thirty-seven-year-old Svengali on the Reed faculty, Stanley Moore, a professor who was destined to become the college’s cause célèbre. A Cal graduate, Moore had previously taught at Harvard where he had earned his Ph.D. in philosophy in 1940. Moore was hired to teach at Reed in 1948 on an accelerated track toward full professorship in philosophy. His peers considered him one of their most outstanding colleagues. The self-avowed Stalinist had been a Communist Party member prior to gaining tenure based on his research and writing on the economics of Marxism.

The son of a wealthy Piedmont, California, family, Moore had married war-correspondent Marguerite Higgins in 1942, but separated from her soon afterward as each pursued their own demanding careers and rumored affairs. He now lived on a romantic houseboat on a river near campus where students flocked to visit him. Bob Richter counted himself among Moore’s admirers, unaware in the fall of 1951 that he was losing his fiancée to Moore’s charms. Moore had already developed a reputation at Reed as a womanizer who often dated undergraduates. With Fay’s uncanny instinct, she had again involved herself with the most controversial figure around. She spent one thrilling month living with Moore on his houseboat that fall, unable to break off a relationship that she knew made no sense. She wrote a lengthy poem about her decision to withdraw emotionally from Bob while immersing herself in a loveless, new liaison. Then she kept it to herself for the time being.

Fay had mentioned Moore in her letters to Bob, but for many months left out the hurtful news of their affair. Yet, as she busied herself on assembling letters of support for Bob’s upcoming parole hearing, she wrote him increasingly critical letters. Going to prison for his beliefs did not make him a saint. Fay suggested it might be better to conform to society’s demands and only reveal one’s true thoughts to a small circle of close friends. At first, she just told Bob she needed time to herself when he was released. By mid-November, Fay told him they were now headed in different directions. Since his mailing privileges were limited, she suggested he would be better off not wasting his time writing to her. Even then she held off revealing her recently ended affair with Moore.

Family issues now preoccupied Fay. During the fall of 1951 Ruby Abrahams had developed vascular problems that required surgery. She convinced her reluctant husband to quit his job in Pennsylvania and return to the Bay Area where they would once again be in the bosom of their families. With no likely job prospects in California, Sam put heavy pressure on Fay to transfer back to Berkeley. He refused to pay for further studies at Reed after the fall semester and insisted that Fay needed to be nearer home because of her mother’s ill health. This time, he did not take “no” for an answer.

Fay felt compelled to return to her mother’s side, though she resented her parents’ heavy-handed tactics. Sam’s pride had kept him from telling Fay that money worries played a key role in his insistence that she switch schools and join them in their new apartment in San Francisco. On reflection, Fay actually felt somewhat relieved by the summons. She thought the challenge of attending Cal was probably good for her, but she refused to live with her parents. Instead, she insisted that the Abrahams pay for a room for her at the International House near campus.

In early 1952, Fay began attending Cal again, eager to find someone with whom to share what Moore had taught her. Fay quickly latched onto Betty Lee, a Chinese immigrant in her political science course. Born in Shanghai, Betty had adopted the English name when she arrived with her parents in California during World War II as a shy and passive 15-year-old who spoke almost no English. Betty’s family lived in Chinatown in San Francisco. She had attended Lowell High School and only moved to Berkeley for college.

At Cal, Fay flattered Betty by aggressively seeking out her friendship as a kindred spirit. The two met often for coffee. Fay was amazed that Betty did not know a Jew from a non-Jew. She captivated her new friend as she passionately expounded on Communism, racism and imperialism. Long afterward, Betty recalled that Fay talked nonstop, “a million miles a minute.” Fay bitterly complained about her forced return to Berkeley and fascinated Betty with details of her torrid affair with Stanley Moore. Moore had convinced her to reject her cloistered upbringing and bourgeois Jewish values. Betty, in turn, felt she received a fascinating insight into American Jewish intellectuals through her friendship with Fay. It was hard to tell the Jews from the Gentiles because most of the Jews she met had long since rejected their religious upbringing and cultural heritage.

As Fay bemoaned her fate and criticized her parents’ values, she did not appreciate the irony that it was she who had insisted on going to Reed — an elite, private college that the Abrahams could ill afford. It was Ruby and Sam who advocated the far more accessible public university that admitted high-achieving immigrants and minorities like Betty. Fay only knew that Reed had opened amazing doors for her. Cal felt like a giant step backward. In 1952, traditional fraternities and sororities still dominated campus life.

Photo courtesy of Karma Pippin

Fay enjoying a trip to the snow with friends from Cal after transferring from Reed. (Likely taken at Lake Tahoe.)

Much to the dismay of both sets of parents, the two friends decided to room together in their own apartment. The Lees were conservative and supported the ongoing Korean War. They considered Fay a bad influence on Betty. Their dislike of Fay hit its peak when Fay criticized Betty’s kindergarten-aged brother Gus in front of his proud father after Gus drew pictures of bombs and airplanes. Fay was not invited back. (A future lawyer himself, Gus later wrote the best-selling autobiography China Boy.)

Betty and Fay remained close friends, though Betty felt she had little to offer her brilliant mentor. Fay frequently interrupted a conversation in their apartment with “Wait a minute,” followed by a trip to her closet where she kept alphabetized 3 × 5 index cards in shoeboxes. The cards brimmed with historical facts, famous authors and notes Fay had painstakingly accumulated over several years. “Any time I had a question she would pull out a shoebox and find the answer,” Betty exclaimed. Their impassioned conversations frequently lasted until one a.m.

Despite their cramped quarters, Betty tolerated Fay’s eccentricities and her disregard for housekeeping. An undisciplined student, Fay often kept the light on, working deep into the night as due dates loomed and almost always pulled A’s. As an English major, she wrote papers every week or two, typing with an impressive staccato style she developed as a pianist. Fay’s eating habits also astonished Betty. Fay still had few culinary skills — scrambled eggs were her mainstay — but Fay had a voracious appetite for meat that she often satisfied with trips to a pet store that sold horsemeat. Fay explained to a skeptical Betty that horsemeat was a staple of French cuisine.

Shortly after she arrived at Cal, Fay joined a chamber music group and started dating a gifted cellist named Stan Seidner. A graduate student in psychology ten years her senior, Seidner was still working on a Ph.D. he would never complete. At the public library in the early spring of 1952, shortly before her twentieth birthday, Fay met another graduate student reworking his dissertation on Shakespeare. Then 28, Robert Gene Pippin would become a lifelong confidante. “Pip,” as he was often called, was brilliant and loquacious. As romantic partners, Pip preferred petite women like his second wife, Anne, who was then finishing her Ph.D. in Classics.

Even though Fay reminded him somewhat of his mother, Pip quickly developed a serious crush on the nineteen-year-old coed. Whenever Fay and Pip met for coffee, conversations between Fay and Pip volleyed like championship ping pong. He was impressed with Fay’s vast knowledge of literature and the way she leapt from one observation to another. Fay was equally taken with Pip’s insights. She was particularly amazed that a Gentile could have such extensive knowledge of ancient Jewish history. As a special gift, she gave him her own leather-bound, official translation of the Old Testament. It would travel with him throughout his life.

When Pip’s wife Anne accepted a teaching job back East, Pip stayed behind at Cal to complete his doctorate. Both Stan and Pip then came often to visit Fay at the small apartment she shared with Betty. As Betty watched their verbal sparring, Fay impressed her as never giving ground to a man. Looking back, Betty characterized Fay as a feminist before feminism was defined by the larger population.

Fay found Pip almost as easy to entrust her innermost thoughts to as her close friend Wendy Milmore had been. Fay told him of her impassioned month with Stanley Moore, including Moore’s penchant for bondage. She said that Moore had transformed her world view. She could not imagine herself pursuing an academic life like the one Pip was headed toward. For her, writing and lecturing on literature was too tame. Fay’s goal became etched in his mind: “Pip, I want the power to change things.”

After nine months, Sam finally found work as a corporate consultant with a pest control company. Sam bought a house in the upscale Claremont Uplands neighborhood in South Berkeley. Sam and Ruby moved in with Lisie, enabling her to finish her senior year of high school at Berkeley High. When Fay introduced Betty, Pip and Stan to her family, Lisie knew that Pip was married, but her parents did not. Sam and Ruby noted that neither Stan nor Pip was Jewish. The Abrahams somehow blamed Betty, believing that Fay’s friendship with Betty reduced her chances of marrying the right man. Fay started sneaking Betty with her on visits to the Abrahams’ new home when no one else was there.

Bob Richter won parole at his first opportunity and was released from prison a year to the day from being jailed. Anxious to see Fay, he invited her to fly to Portland in February of 1952. Fay had written him in December to let him know her parents had moved back to San Francisco and she was joining them for Christmas. She no longer intended to marry him, but had torn up several drafts of letters that explained why. By early February, she felt obligated to confess her betrayal of their relationship with Stanley Moore the prior fall. Yet she sent contradictory signals when she then joined Bob in Portland for a passionate couple of days that meant far more to him than to her.

In April, Bob came down to Berkeley during spring break anticipating Fay to be waiting for him with open arms. Instead, she met him in the parlor room of International House and suggested they talk there. Only then did Bob fully appreciate that Fay had cast him aside. As he began discussing what he would do while waiting for her to finish college, Fay stunned Bob with news that she had just decided to go to law school. She told him that she did not think it made sense for him to wait for her. Miserable and befuddled, Bob headed back to Portland.

While at Cal, Fay occasionally saw her friend Hilde on trips home from college to see family. Hilde had transferred from Reed to Cornell her junior year. As a student of modern philosophy, Hilde considered herself far more progressive than Fay, whom she still regarded as relatively apolitical. On a double date weekend trip to Monterey during Fay’s senior year, Fay also startled Hilde with news of her intention to go to law school. Hilde wondered what, if anything, her flamboyant friend would wind up doing with her law degree.

In fact, Fay had for some time admired her free-thinking older cousin who was a lawyer. Fay herself was now paying closer and closer attention to the swirling First Amendment controversies around her. She had signed up for an undergraduate constitutional law course and began to explore law schools. Twenty years later, reflecting on her mindset back in 1952, Fay explained, “I felt people who were lawyers … might be listened to.”4 Fay also credited the esteem her parents placed on higher education and pursuing a career. Unlike most others of their generation, they had not expected either her or her younger sister to simply aspire to grow up to be a housewife. But as Fay well knew, Sam and Ruby never envisioned their gifted first-born becoming a lawyer.

Photos courtesy of Karma Pippin

These photos of Fay were likely taken on a trip to Carmel her senior year at Cal. That was when she surprised her friend Hilde with news she planned to apply to law school. She explained to her new close friend Pip, “I want the power to change things.”

By Fay’s college days, she had likely read Irving Stone’s popular biography, Clarence Darrow for the Defense, detailing the legendary lawyer’s successes as a defender of the poor and downtrodden. But lawyers like Darrow derided women as unfit for what was then the most male-dominated profession in America. By the early 1950s, women were still only three per cent of law students, but Fay fit the profile of those who obtained the best formal training — the first child in a middle-class, educated white family.

Female role models remained few and far between. When Fay was a junior in college, Governor Earl Warren finally appointed the first woman judge in Fay’s home county, Cecil Mosbacher, a conservative veteran prosecutor. Fourteen years would go by before the next woman was appointed to the local bench, a year after losing a contested election for an open seat to a rival who campaigned as “a man for the job.” Being Jewish added another layer of difficulty for Fay. In Unequal Justice, historian Jerald Auerbach noted, “The doors of most … law offices were closed, with rare exceptions to a young Jewish lawyer.”5 Yet Fay could look to the success of Louis Brandeis, who had first gained fame as “the people’s lawyer.” Brandeis had made his name crusading for social causes before his historic appointment in 1916 as the first Jewish Supreme Court Justice.

Fay most admired Felix Frankfurter, who held the “Jewish seat” on the high court when she was in college. A former Harvard professor, Frankfurter was also a champion of unpopular causes, who gained notoriety for his scathing criticism, published in the late 1920s, of the way in which the murder trial and appeals of anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti had been handled. Frankfurter considered their execution a blatant miscarriage of justice.6

By June of 1952, Fay was on a mission. She took additional courses to finish college on an accelerated schedule. Her younger sister Lisie had just started her freshman year at Cal. Fay took time to give Lisie pointers on note-taking, but never invited Lisie to her apartment — likely for fear Lisie would share details of Fay’s home life with their parents. Lisie was then dating her future husband, Don Stone. The two would invite Fay to join them on picnics and grew concerned at her chronic melancholy.

Fay could not bring herself to confide in her sister her abruptly terminated love affair with Stanley Moore, whom she saw again briefly in Berkeley during the summer of 1952 when he was down from Oregon visiting family. Fay realized that no one in her family would appreciate her obsession with a married Reed professor nearly twice her age or the radical ideas to which he had exposed her. Instead, Fay offered opinions to Lisie and Don on a wide variety of other subjects, including sometimes in Don’s own field of science as a pre-med. Unlike Betty Lee, Don learned to be skeptical of Fay after a few instances in which she made a puzzling pronouncement or cited a spurious authority. Fay, in turn, felt disconnected. She assumed her sister would marry Don and, like their parents, head for the safe, middle-class life in the suburbs that Fay so actively shunned. There was Lisie again setting the example of the good girl Ruby desired her namesake first daughter to become.

The Abrahams would have been apoplectic if they had known that the FBI had opened up a file on Fay and her roommate Betty Lee in the fall of 1952. The FBI informant was a returning disabled veteran who considered it his civic duty to report other students and teachers whom he believed to be Communists or have Communist sympathies. At the time, an Army manual listed a number of expressions that one might overhear Communists using in conversation such as “chauvinism, colonialism, ruling class, witch-hunt, reactionary, exploitation, oppressive, materialist, progressive.”7 Fay likely used such words in conversations with Betty, as did thousands of students and faculty on liberal college campuses throughout the United States. A million dossiers on Americans would be compiled for the House Committee on Un-American Activities during its thirty years of activity.8

The FBI agent who opened Fay’s file candidly described the informant as “somewhat irrational” and acting on “nebulous or almost completely insignificant” observations, but still wrote up Fay Ethel Abrahams and her foreign-born roommate. Neither had any history of suspected activity, but the agent noted, “They have male friends who visit them and they are gone until late at night.”9

SOURCE: FBI file on Fay Stender, Vol. 1

Fay first became a blip on the FBI’s radar screen in September 1952 when she was a senior at Cal – just one entry. The FBI agent considered the informant “somewhat irrational” and his observations “nebulous or almost completely insignificant.” Yet the agent duly recorded the address of Fay and her foreign roommate [Betty Lee] and noted, “They have male friends who visit them and they are gone until late at night.”

Dating back to 1940, the University of California had an informal policy in place against the hiring of known Communists. Yet growing paranoia throughout the next decade fed the assumption that Cal still ran the risk of being overrun by Communists. In 1949, the Regents instituted a formal loyalty oath and fired eighteen professors who refused to sign it. The professors’ reinstatement in 1951 came only after the ACLU obtained a ruling that the Regents’ acted unconstitutionally. The administration’s attempt to muzzle campus political dialogue would simmer for years and ultimately erupt a decade later in the Free Speech Movement, with Fay among those at its forefront.

In the ’50s, of the 69 faculty members dismissed throughout the nation during the McCarthy Era, 31 were at the University of California. Others were scattered among 26 other colleges. As Fay well knew, one of the academics at the center of this political storm was Stanley Moore, whom Reed would be forced to fire in 1954. Moore suffered the consequences to his career for many years afterward. The controversy on the liberal campus reverberated for more than forty years, with Bob Richter leading the charge among Reed alumni in the 1990s to have the trustees apologize and its president welcome Moore back. Only then did Moore reveal that he had quit the Communist Party in 1953 in protest over mass arrests and anti-Semitic persecutions by Stalin. When Moore was hauled before HUAC in 1954, his refusal to answer the committee’s questions had been solely a matter of principle.

* * *

Fay graduated Cal in January of 1953 with honors in English. Still under Stanley Moore’s lasting influence, she felt no loss in missing the June celebration with its senior ball, beach party, banquet and barbeque. But the class motto seemed appropriate: “The sky’s the limit.” She obtained a part-time job at the Bacteriology Department at Cal. Fay worked as a secretary, while she enrolled in graduate school courses in political science and looked into law schools.

The University of Chicago Law School had a reputation as one of the best in the country. It also generated excitement among progressives familiar with Professor Karl Llewellyn, who had just recently joined its faculty after a quarter of a century at Columbia. He was one of the leaders at the time of the “Legal Realism” school of thought developed in the first half of the twentieth century — the belief that the law was a flexible tool which balanced competing interests to accomplish particular public goals. Legal Realism would later be credited as the forerunner of a number of multi-disciplinary programs in law and economics, political science, feminist theory and racial studies.

The University of Chicago Law School had a large Jewish contingent of students and professors and, in 1953, was one of the top ten choices in the nation for women applicants. It also offered a full academic scholarship. This was key. Annual tuition was $738, several times the cost of a legal education in state law schools. Fay’s parents would not support her going to graduate school in Chicago. Fay eagerly registered for the new LSAT, given in February, obtained letters of recommendation and accompanied her application with a short essay on Chaucer, the $5 application fee, and a recent head shot of herself in ponytail and bangs.

Fay also described a novel project she proposed to undertake in law school — looking for correlations between the judges’ political party and their rulings in various types of cases. Maybe that was what caught the admissions’ committee’s attention. In the last week of June, Fay received her letter of acceptance, followed a month later with a full tuition scholarship. Fay was Chicago bound.

Fay Abrahams, U.C. Berkeley senior year, 1952

Photo courtesy of Karma Pippin

Fay included a recent head shot of herself in ponytail and bangs with her application to the University of Chicago Law School. She received a full tuition scholarship to attend that fall.

Source: https://www.facebook.com/pg/UChicagoLaw/photos/?tab=album&album_id=414378531279

The University of Chicago Law School was known for promoting “Legal Realism” – the belief that the law was a flexible tool that balanced competing interests in pursuit of societal goals. Legal Realism was the forerunner of future multi-disciplinary programs in law and economics, law and political science, feminist theory and racial studies.