Читать книгу CALL ME PHAEDRA - Lise Pearlman - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

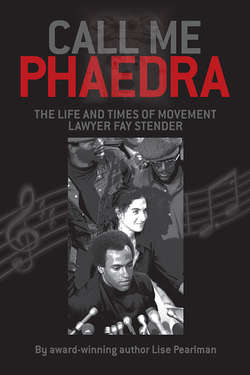

ОглавлениеPrologue

The gunman waited in the shadows near Fay Stender’s front door as his companion rang the buzzer. It was after one a.m. on a quiet, tree-lined section of Grant Street in the flatlands of West Berkeley within walking distance of the police station. A young, half-dressed man, turned on the porch light and pushed aside the frayed front door curtain. He saw a light-skinned black woman standing on the doorstep and he immediately thought she must be in distress to arrive at his family home at that hour. As he opened the door, she quickly turned and ran while a black man wearing a leather jacket and a blue knit cap suddenly forced Neal Stender back inside the house at gunpoint. He then made Neal lead him to Neal’s mother as she lay sleeping upstairs. The gunman followed Neal into the master bedroom and was surprised to find two women in the bed and a dog lying on top of the covers near their feet. Once Fay identified herself, the gunman told her to put something on. Her nakedness made him uncomfortable. When she had donned a nightgown in her closet, the gunman then asked her if she had ever betrayed anybody. He mentioned George Jackson, the revolutionary Soledad inmate who had fired Fay as his lawyer in early 1971 and months later died in an escape attempt from San Quentin. Fay denied that she had betrayed Jackson or anyone else.

The gunman then forced Fay to sit at her desk to write, “I, Fay Stender, admit I betrayed George Jackson and the Prison Movement when they needed me most.”

Fay chided the gunman. “I will write this because you have a gun,” Fay said. “But it is not true.”1 When she finished her “confession,” the gunman put it in his pocket. Then he asked his three hostages for money and left Neal and Fay’s lover Katherine Morse (a pseudonym) tied up. Fay offered to lead him downstairs, where she offered him a twenty-dollar-bill fetched from her kitchen drawer. Instead of taking it, he shot her five times at close range and fled out the front door, disappearing down the quiet street as she cried out for help.

The shooting early that Memorial Day of 1979 dominated local radio and television reports. Banner headlines in Berkeley and Oakland papers proclaimed, “Attorney shot, near death”2 and “Political Murder Try?”3 Then national wire services picked it up. For the next nine months, Bay Area media covered every development: the arrest of the suspect, his attempted escape, the contentious preliminary hearings, and the dramatic trial. Newspapers speculated that the attacker belonged to a notorious prison gang that traced its founding back to death row “Soledad Brother” George Jackson, who was killed in the prison yard at San Quentin in August 1971, days before he was to face trial for the murder of a guard at Soledad the year before. After the home invasion that nearly killed his wife, Fay’s husband Marvin considered his family to continue to be at extremely seriously risk. He acquired a gun permit, armed himself and hid their two children thousands of miles away, while Fay remained, incapacitated, at another secret location in the Bay Area.

At first, no one knew if the forty-seven-year-old lawyer would survive. If she did, would she be willing to become the star witness for the prosecutor? Few reporters failed to mention the irony of the District Attorney determinedly seeking justice for a victim most members of his office despised as an enemy — a woman state prison officials nicknamed “The Dragon Lady.”

Fay had once considered this slur a badge of honor. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, she had nothing but contempt for the state correctional hierarchy. She took great pride in her zealous legal representation and political organizing on behalf of Black Panther co-founder Huey Newton and death row inmate George Jackson, both accused of killing lawmen. In championing the causes of the two revolutionaries, she remained undaunted by whispered rumors that Oakland police officers used her image for target practice.

The scathing labels were, in fact, recognition of her extraordinary effectiveness. The soft-spoken attorney considered herself an impassioned insider working within the legal system to transform society’s attitude toward ghettoized blacks and prisoners’ rights. Fay Stender’s successes made her far more threatening to the established social order than two other radical American women pilloried by the establishment at the same time — glamorous actress and anti-war demonstrator Jane Fonda and Communist lecturer and accused kidnap-and-murder conspirator Angela Davis.

But who was “The Dragon Lady” really? Almost forty years later, Fay Stender’s admirers consider her a martyr to her pioneering work in California prison reform. At the height of her career, Fay was one of the most sought after “people’s lawyers” in the nation. A client with a cause could not find a more energetic advocate. But in spite of her successes, many colleagues believed that Fay’s untempered empathy for her clients compromised her professional judgment.

Friends could easily picture Fay as the heroine of a grand opera. A highly talented musician, she had been a child prodigy who gave up training for a career as a concert pianist during her rebellious teenage years. The five-foot-eight, dark-haired advocate often appeared striking and glamorous, whether she was passionately defending the merits of her favorite novelist, Marcel Proust, or decrying unfair penalties faced by black prostitutes, but not their “johns”. Though fiercely devoted to her children, she believed the Movement came first, a commitment to political activism shared by her husband Marvin through a quarter of a century of an intermittent and unpredictable marriage.

At gatherings, Fay often dominated the conversation, while waving her expressive hands for emphasis. Upon meeting her, many people found her charismatic; she exuded an aura of sexuality not unlike that of presidents John F. Kennedy and Bill Clinton. Yet cameras seldom did Fay justice. When she was animated, her face glowed. At other times, her mood swung from contagious passion to deep melancholy. Then she might come across as eccentric and oblivious, wearing mismatched, dowdy outfits or letting her slip show. Afraid of guns herself, she acted as a cheerleader for clients bent on armed confrontation with police. Yet she never identified with the anarchism of her revolutionary clients or the militancy of some of her young Leftist colleagues.

As much as Fay worked to bring like-minded radicals together, she was also at the center of the most enduring rifts among Leftists in the tight-knit East Bay community. Muckraker Jessica Mitford — who collaborated with Fay on prison law reform — put Fay firmly in the category of “frenemy.” Some colleagues found Fay’s inflexibility repellent and questioned the course she charted; others felt used and dismissed when Fay’s focus shifted and she no longer needed them. Yet Fay always found new collaborators as she forged ahead to her next cause célèbre.

The May 1979 home invasion left Fay both wheel-chair bound and devastated. While under twenty-four hour a day police protection, she repeatedly announced that her only motivation to live was to help convict her assailant. She told the few friends admitted to her San Francisco hideaway to “call me Phaedra [pronounced ‘Fay-dra’],” a tragic heroine from Greek mythology. In college, Fay had been fascinated by French playwright Jean Racine’s masterpiece, Phèdre, the retelling of the story of the ancient queen Phaedra, daughter of King Minos of Crete. Phaedra came under the spell of the goddess Aphrodite and fell hopelessly in love with her stepson, Hippolytus, whose mother was the queen of the Amazons. Hippolytus rejected his obsessed stepmother, who sought to make him king. On the return of Phaedra’s husband, King Theseus, Phaedra accused Hippolytus of attempting to usurp the throne. Outraged, Theseus had Hippolytus killed. The guilt-ridden Phaedra then killed herself.

Racine followed the classical formula that hubris leads to downfall. Fay saw parallels between Phèdre’s ill-fated sexual obsession with her inter-racial stepson and Fay’s own flouting of traditional taboos in becoming obsessed with her black clients Huey Newton and George Jackson. Ten years her junior, both young militants brought out Fay’s strong maternal instincts as well as her passion. At the outset, Newton and Jackson greatly appreciated Fay’s legal help. But the two radicals later emphatically rejected her as too controlling — a Liberal white Jewish woman who affronted their macho Black Power image with her determination to shape the world’s perception of them as sympathetic victims of a racist justice system. Though Fay seemingly bounced back from her rejection by both revolutionary clients to champion other causes, she, in fact, never fully recovered.