Читать книгу CALL ME PHAEDRA - Lise Pearlman - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление∎ 5 ∎

Renewed Ardor

“Whereas the law is passionless, passion must ever sway the heart of man [and woman].” 1

— ARISTOTLE

The newlyweds celebrated their marriage a second time with a large wedding reception for family and friends at the Abrahams’ home in Berkeley. Fay was excited to be reunited with her old companions, oblivious that her younger sister had delayed her finals in hopes of spending more time with Fay. It must have raised eyebrows in the Abrahams’ social circle when Fay and Marvin then decided to start out married life by sharing a house with Betty Lee. For a surprisingly affordable price, the trio rented a large home in the Berkeley Hills that resembled a drafty, Italian villa. Betty thought Fay had found a real gem of a husband. She was surprised and delighted that Marvin took his turn washing or drying dishes without a murmur, unlike all the other men Betty had met.

Betty remained one of Fay’s few confidantes about Stanley Moore’s ongoing troubles. In the summer of 1954, a group of influential Oregon businessmen pressured the trustees to ignore the faculty and fire Moore or see Reed closed. Moore kept silent on his party affiliation throughout the political storm, but challenged the trustees to consider that they might stand condemned by history for their action should they reject the faculty’s ringing endorsement of his fitness to teach. The trustees yielded to the outside pressure and fired Moore, outraging faculty and students and prompting the college president to resign. In spite of her distress at this alarming turn of events, Fay likely felt enormous relief at not having been caught up in Moore’s public shaming and ostracism.

* * *

Though Marvin had to hunt for a job, Fay already had hers secured. Dag Hamilton’s in-laws had just rented a house in Berkeley. Walton Hamilton, then in his early seventies, had been an economist in the Roosevelt administration. The retired law professor remained still as sharp as a whip, but almost totally blind and in need of a reader and researcher. Fay and “Hammy” quickly proved even more simpatico than Dag had anticipated. Fay read him music and art books and shared his satisfaction as the Indian rights case he was working on progressed toward the United States Supreme Court.

When Professor Sharp came out to the Bay Area that summer to visit his son, he stopped by to ask Fay and Marvin for help. He was fund-raising for the Rosenbergs’ two orphaned children then being reared by another family. Marvin immediately began passing out leaflets at a factory gate in Emeryville. This time Marvin’s decisiveness alarmed Fay. She confided her panicked reaction to Betty. It was too dangerous. Fay pictured a steel worker punching Marvin or the FBI adding him to their list of undesirables. Yet, despite agonizing over the issue, Fay soon swallowed her fears and joined Marvin. In the years to come, Fay would take far greater risks, once she concluded that there was no safe middle ground on which she could live with herself.

After a heady summer of intellectual dialogue with Hammy, Fay came down to earth with a crash when she arrived for classes at Boalt Hall. Fay had grown up with only a dim awareness of the nearby law school as a more prestigious alternative to Hastings in San Francisco. In deciding to transfer from the University of Chicago, Fay had simply assumed that it would provide a parallel experience. She did not realize that no Malcolm Sharps could be found on its conservative faculty, whose members had all signed a loyalty oath and remained totally silent on the issue of forced relocation of Japanese-Americans during World War II. Even among Boalt students in the early ’50s, being a Democrat was unusual and passed for flaming radicalism.

Within days after starting classes, Fay begged Marvin to return to Chicago. Marvin had by then obtained a temporary job as a law clerk for the office of famed torts attorney, Melvin Belli. Unlike her parents’ reaction when Fay had demanded to switch schools in the past, Fay found Marvin completely supportive of her wishes. He suggested to his distraught bride that she call Dean Levi. Marvin later recalled that when Fay reached Dean Levi to ask if she could undo her horrible mistake and get her scholarship back, he laughed and said, “Sure.” The earliest that the University of Chicago would accept her return was for the spring term. In the meantime, Fay told Marvin “I can’t stand it here” and immediately withdrew from Boalt. She had lasted only a week.

So far Fay’s iron will and headstrong, passionate nature set the path for her and Marvin. She decided to use the unexpected window of time before they moved back to Chicago to tackle a reading project her friend Pip likely encouraged — reading the English translation of the entire seven volumes of Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past (A La Recherche Du Temps Perdu). The ambitious work with 2,000 literary characters had received acclaim as the greatest novel of the century, perhaps, the best ever written. As usual, Fay immersed herself completely in her latest project. She was fascinated by the author’s reflections on time and memory, the role of the subconscious and of art and music in life among the French aristocracy and the emerging French middle class. Taking full advantage of Marvin’s indulgence, Fay spent hours on end reading chapters and trading insights with her friend Pip over coffee at outdoor cafes. This interlude had a lasting impact. Fay would name her only daughter for Proust’s heroine, the Duchesse Oriane de Guermantes, and, in her late forties, immerse herself in her own self-reflective, lengthy sojourn in Europe.

Meanwhile, Marvin left the chaotic Belli law office and worked as an editor for the legal publishing company Bancroft Whitney. When Fay tore herself from the adventures of the Duchesse Oriane de Guermantes, she sometimes joined Marvin for lunch in San Francisco. His new work address was right across the street from Hastings School of the Law. One day in the early fall, Fay suddenly recognized a young woman on the steps of the publishing company as Alice Wirth. Fay surprised her former law school classmate by greeting her as if she were one of Fay’s oldest and dearest friends. The two acquaintances had mostly spent time together in a first-year study group.

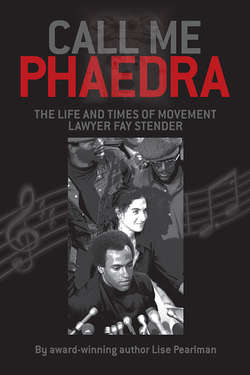

Source: The Berkeley Historical Society, Ying Lee: From Shanghai to Berkeley (2012)

Fay and Marvin Stender with their friend Ying “Betty” Lee when she stayed with them in Chicago in the fall of 1954.

Alice was now Mrs. Gary Gray. Since leaving Chicago, she had reenrolled in the four-year law school program at Hastings as a first-year student. Fay was incredulous. She considered Hastings a dreadful school, a factory not suitable for someone who cared about the public good. Fay invited Alice to bring her husband to Fay and Marvin’s home in the Berkeley Hills for dinner. The house impressed Alice as damp, dark and Gothic. Marvin caught Alice looking skeptically at the meal that Fay placed on the table — two cans of Dinty Moore beef stew, baked potatoes and sour yogurt, a product not widely in use at that time. Marvin firmly told Alice and Gary, “This is the way we eat.” Alice found Marvin blunt; Fay found her husband’s emphatic dismissal of bourgeois culinary skills another of his endearing qualities.

One afternoon, Fay asked Alice to walk with her to the San Francisco municipal court to see if they could observe a jury trial. Fay’s flamboyant outfit included several bangle bracelets which clattered whenever she moved. Alice and Fay discovered a case in progress, opened the door and spotted available seats all the way in the front. The entire courtroom stared open-mouthed as Fay noisily made her way forward with Alice in tow. The pair stayed all afternoon to hear the details of a woman’s slip and fall on a shattered jam jar at a local Safeway grocery store. It amused them both that neither attorney could correctly pronounce the names of the plaintiff’s broken tibia and fibula. These bumbling litigators were undoubtedly among the men who were so dismissive of women law students.

Heeding Fay’s sharp criticism and her own mounting dissatisfaction, Alice soon quit Hastings. She and her husband Gary spent many evenings socializing with Fay, Marvin and Betty. When they discussed music and literature, Fay mostly did the talking, mesmerizing Alice both with her intelligence and with her phenomenal talent on the organ installed in the Stenders’ living room. Fay also dominated their frequent political discussions, though she still lived in great fear of the Cold War. The boldness that later characterized Fay’s public persona took years to develop.

* * *

Dean Levi was quite tickled by Fay’s return to the University of Chicago law school after just one semester’s absence. He told anyone who would listen how his law school was considered by a woman student to be so much better than the law school she transferred to that she immediately sought to retransfer. Fay eagerly started attending classes while Marvin went to work for Professor Hans Zeisel on an experimental jury project that Dean Levi had launched two years earlier with a grant from the Ford Foundation. The project ultimately took fifteen years and cost the staggering sum of one million dollars to publish a definitive study of criminal trials. Some of the findings set forth in The American Jury later played a key role in assuring a diverse and sympathetic jury for the Huey Newton murder trial.

The outrage of Chicagoans at Mississippi’s lack of justice temporarily took the focus off of Chicago’s own largely unaddressed race problems, which Fay observed daily in her run-down Hyde Park neighborhood. When Betty Lee came to visit that fall of 1954, Fay delighted in giving her friend a tour of the ghetto she had originally found so appalling. Marvin’s father was himself a local landlord. Betty had just emerged from an intense love affair, feeling wounded and looking for a place to recover, which Fay and Marvin gladly offered. In the close quarters of their apartment, Betty again became accustomed to Fay’s late night staccato typing. She felt sorry for Fay’s classmates, knowing that Fay brought her typewriter to exams and likely unnerved anyone seated nearby. By mid fall, Fay’s interest had alighted on local politics. Abner Mikva, whom Marvin had met at the jury project, was making his first run for state office. Fay and Marvin joined Mikva’s volunteers, while their friend Betty Lee joined his paid staff.

In the spring and summer of 1955 Fay concentrated on her studies, finding it increasingly difficult to suppress her disapproval of how the law aided the haves over the have nots. Meanwhile, with many of their old friends gone, she cultivated new friendships at the law school, including Brian Gluss, a young Ph.D. in mathematics from Cambridge University, who had been hired to assist on the jury project on a one-year worker’s visa. With his heavy accent and eccentric habits, this tall, skinny Brit in army shorts stood out in sharp contrast to the rest of the jury project staff. Brian also liked to live dangerously, a wild partier who often hung out at black clubs with an inter-racial couple from the project.

Fay often played Beethoven sonatas on the grand piano in the lounge at the International House where Brian lived. She drew him out in private conversation, unearthing painful secrets he had not spoken of in fifteen years. His parents had fled devastating pogroms in the Ukraine for London in 1906, around the same time Fay’s ancestors fled the border city of Brest-Litovsk. As she coaxed Brian to share his stories, she was soft-spoken, gentle, and reassuring. Years later, those nurturing traits disarmed her most aggressive black militant clients. In response to her probing questions, Brian revealed to Fay that he had been a survivor of the London blitz during World War II: the bomb that hit their home left him and his parents with only a few scratches, but killed his visiting grandmother and his twelve-year-old brother in the next room. His parents had never recovered.

* * *

After the summer quarter ended, Fay and Marvin returned to the Bay Area for Labor Day weekend. Fay played the piano for her sister Lisie’s wedding to her long-time boyfriend Don Stone at a small ceremony in their parents’ home in Berkeley. That same weekend, national and international headlines decried the apparent lynching in Mississippi of black Chicago teenager, Emmett “Bobo” Till. Emmett’s gruesome remains were displayed in an open casket visited by thousands of mourners at an African-American church in Chicago’s South Side, not far from where Fay and Marvin lived. The murder of Fay and Marvin’s neighbor Emmett Till would ignite the Civil Rights Movement.

Fay now took her studies far more seriously. In her third year she took antitrust law from Dean Levi and earned a high A from him. Generally perceived as a cool, unemotional person, he spoke of Fay glowingly at alumni functions. The esteem he held her in undoubtedly dissipated over the years as he became increasingly conservative. He was later appointed President of the entire University of Chicago and ultimately named United States Attorney General for Republican President Gerald Ford. By that time, Fay had gained a national reputation for radicalism.

Yet Dean Levi had a temporary sojourn as a suspected Lefty in the eye of a national political storm himself, during the quarter that Fay took his course, and it centered on his ambitious jury project. In October, all hell broke loose. Brian Gluss feared he would lose his worker status and be deported. Marvin, as the sole support for himself and Fay, also had his job on the line. It was another lesson close to home, underscoring the dangerous third rail of the McCarthy era in politics.

The jury project on which Marvin was working had started as a small study of jury deliberations to refute critics who ridiculed jurors as mere pawns of veteran attorneys. The designers of the project anticipated tape-recording a hundred jury deliberations with the consent of the lawyers on both sides. Though the experiment was backed by the Chief Judge of the circuit, some judges and lawyers became immediately alarmed at the idea of “jury bugging.” The Department of Justice strongly opposed the project, which conservative radio commentators derisively dubbed jury “snooping” and trumpeted as a national scandal.

As a liberal think tank, the University of Chicago remained under great suspicion that it might be infiltrated by Communists. In early October of 1955, Dean Levi was called to Washington, D.C., to appear in front of a House subcommittee investigating whether the law school was attempting to undermine the integrity of the entire American jury system. Warren Burger, the future Chief Justice, and then Assistant Attorney General, accused the law school of plans to eavesdrop on 500 to 1,000 juries nationwide.

This public display of shocked disapproval contrasted markedly with the Department of Justice’s own secret program. In the spring of 1954, Attorney General Brownell had secretly authorized bugging by the FBI in the purported interests of national security that defied limitations recently imposed by the Supreme Court. The FBI then installed hundreds of electronic bugs in traditional criminal investigations totally unrelated to national security.

None of this was public when Congress grilled Dean Levi about the jury project or when President Eisenhower followed the hearing up with a call for a ban on bugging juries in his next State of the Union speech. Congress responded by adopting a new federal law, outlawing the secret recording of jury deliberations. The media soon moved on to other concerns.

Meanwhile, Fay turned her focus to an impetuous personal project. She talked her friend Alice Wirth Gray into asking her influential mother to help Fay and Marvin adopt an eleven-year-old homeless Wisconsin Native American girl. It would be an uphill battle given that the couple were only 23 and 24 and married for less than two years. A very dubious Mrs. Wirth then wrote letters to help facilitate the inter-racial adoption only to learn a few weeks later that Fay decided it was all a mistake and no longer wished to pursue the adoption. Fay was oblivious to what she had put Mrs. Wirth through to support the ill-conceived adoption efforts. (Over the course of Fay’s career many people who did her favors felt similarly used and unappreciated.)

The next semester Fay and Marvin house sat for Professor Sharp while he was on sabbatical. Entertaining friends in his posh penthouse overlooking Lake Michigan, Fay enjoyed the life style of the upper middle class. When on an emotional high, as she was at the time, Fay had the capacity to assume that whatever choices she made were consistent with her Leftist ideology. This one was easy. After all, the apartment belonged to the President of the Lawyers Guild, who offered it to the couple for free.

By taking summer courses, Fay made up for her lost quarter following the transfer to Boalt. In June of 1956, Fay obtained her law degree with the rest of her class and finished in the top third. Fay and Marvin applied for jobs in both Los Angeles and San Francisco but received no offers. At Fay’s urging, they once again headed for the Bay Area, this time with a letter of introduction from Professor Sharp to two prominent Leftist lawyers in San Francisco, Charles “Charlie” Garry and Benjamin “Barney” Dreyfus, whom Professor Sharp had come to know well through their many years together in the Guild. Fay and Marvin packed their few belongings, their diplomas and their idealism and headed west for good.