Читать книгу CALL ME PHAEDRA - Lise Pearlman - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление∎ 7 ∎

Turbulence

Fay … surveys the tangled jungle and … offers a toast:” To chaos.”1

— JUDITH NIEMI

Fay became pregnant in the early fall of 1957, finished her classes and prepared for the baby to arrive. Marvin had found work as an associate in the offices of Martin Jarvis in San Francisco, trying criminal defense and personal injury cases. Marvin’s new boss was among the most stalwart of the small circle of local lawyers, including Charlie Garry and Barney Dreyfus, who had challenged political persecutions during the Cold War. As Marvin worked long hours, Fay retrieved from her cousins the bassinette her parents had bought to welcome her own birth and made it ready for her infant son, born the first week of June 1958. The delighted new mother named her baby Neal as an anagram of Lena, her favorite grandparent. Fay gave Neal the middle name Aviron for her paternal grandfather’s Russian family.

Fay decided to nurse Neal. By 1958, when Neal was born, breastfeeding in the United States had dropped to close to 20 per cent and the term was not even accepted in polite company. By then, Fay and Marvin had moved to a rental cottage in a wooded area of Palo Alto. Often isolated, Fay surprised some of her old friends by taking up the cause of the newly formed La Leche League. They, too, supported breastfeeding, but found the organization too preachy.

Fay also found herself drawn to join those who challenged the modern opposition to natural childbirth. Expectant mothers, discouraged from home births as outmoded and too painful, were instead rushed to hospitals where obstetricians made nearly all the decisions. The mother was often anesthetized. The father, prohibited by law from entering the delivery room, was consigned to waiting in the hall or visitor’s room for some word about his wife and newborn. The child was commonly delivered by forceps and then whisked off to a communal nursery tended by hospital personnel.

Realizing that her brother-in-law Don now had medical privileges as a new doctor, Fay convinced her pregnant sister to get Don to join her in the delivery room. Lisie had already suffered one miscarriage. Don grew alarmed when his tiny newborn daughter showed signs of serious problems, but said nothing until the crisis had passed. At Fay’s urging, Lisie immediately started nursing her new baby, Linda, who quickly lost ten ounces and weighed slightly over five pounds by her tenth day. Lisie’s alarmed pediatrician warned, “Well, Mother, you keep this up and she’ll be in an incubator next week.” Fay insisted that her sister ignore the doctor’s advice and was angry when Lisie instead switched to bottled formula.

Fay herself had been nearly eight months pregnant when Lisie gave birth. In late January of 1960, Fay had her own newborn daughter, Oriane. Soon Fay’s toddler Neal nicknamed Oriane “Fifi,” and the name stuck throughout her childhood. Fay stayed home with her babies essentially full-time for three years. In an interview at the height of her career, Fay recalled only the joy she had experienced as a new parent. Yet, at the time, she grew increasingly depressed. She could not keep up with the demands of motherhood and had no desire to manage a household. So she threw her energy into another cause — an organization recently formed in Los Angeles, the International Childbirth Education Association.2

Fay embraced ICEA’s promotion of freedom of choice in childbirth and family-centered maternity care. Best of all, the loosely run organization gave her lots of latitude. Fay received the lofty title of Western Regional Director, a post she held for the next four years as she busied herself with ICEA and La Leche League projects. She authored a widely distributed pamphlet, “Husbands in the Delivery Room,” and listed her home phone as a resource for new mothers under the name “Nursing Mothers Anonymous,” with the slogan, “Don’t reach for the bottle, reach for the phone.” With help from a local lawyer, Fay brought suit to challenge a hospital policy that then barred fathers from delivery rooms. The case resulted in a settlement through which the hospital agreed to change its practice.

All the while, Fay’s relationship with Marvin deteriorated. By the end of 1960, he was routinely gone for long days, leaving Fay miserable and lonely. When Fay learned that Marvin was involved with another woman, she concluded her marriage had failed. Fay made a distraught call to her sister Lisie in San Diego, where Don was fulfilling his postponed military service following completion of medical school. Lisie and her husband welcomed Fay and her two young children unhesitatingly to their tiny, two-bedroom home.

Fay returned to the East Bay a few weeks later, in early 1961, to rent a small apartment in Berkeley for herself and her two small children. Still despondent, she channeled her pain into a sixteen-line poem and sent it to her close friend Pip. Fay told him she thought haiku would have matched her feelings better, but found herself “too turbulent” inside to express herself in this simple Japanese form, as the rainy winter weather persisted. Nursing her baby gave her pleasure, but her consignment to domestic tasks left her feeling isolated from political movements. She wove into her poem literary allusions that she knew Pip would appreciate. Yet she could not help also sharing her despair at “keeping down the terror ….”3

Pip grew quite anxious about Fay’s depressed mood. Likely through his connections in Cal’s English Department, Fay was soon offered a job teaching an introductory speech course to undergraduates. Ruby volunteered to help with Neal and Oriane during the week. On Saturday mornings, Fay brought the children to her parents’ home where Marvin would fetch them at day’s end to spend Saturday night and Sunday with him and his current girlfriend. Yet, on weekdays, single parenting still overwhelmed Fay.

Fay and Marvin’s acquaintances in the Guild were not surprised by their separation. Some thought Fay was single-minded and humorless, difficult to get along with. Marvin’s easygoing nature often seemed to bore Fay. She continued to delight in caustic, verbal sparring with men, which was not Marvin’s style. He, in turn, had developed a reputation as a ladies’ man. Long before she fled to her sister’s, Fay had broadcast her unhappiness to friends, frequently complaining that her husband did not offer her enough emotional support. To a few close friends, Fay confided her own continued obsession with Stanley Moore. Since 1957, Moore’s career had been on the rebound following publication of The Critique of Capitalist Democracy, which synthesized the writings of Marx, Engels and Lenin. He had meanwhile separated from his second wife. In 1960, Stanley was at work on another ambitious book while Fay battled with postpartum depression and her own unrealized aspirations. Fay had fantasies of ending her broken marriage and reuniting with Stanley.

A more practical idea for adding meaning to her life soon came to Fay. As she nursed her newborn, and chased after her toddler, Fay followed political developments related to the most recent HUAC hearings in San Francisco focused on exposing Communist affiliations among California teachers. When police had hosed protesters down the steep steps of City Hall and conducted mass arrests, “Black Friday” May 13, 1960 had made national headlines. In April of 1961 Charlie Garry and former prosecutor Jack Berman represented Robert Meisenbach, the lone prosecuted defendant. The trial was all over the front pages and the talk of the Leftist community. By then, Fay had had enough of being a stay-at-home mom and part-time teacher. She asked Garry once again if he might hire her. Garry made Fay an offer on a part-time basis, contingent on her successfully completing a research project for his partner Barney Dreyfus. Garry knew that Dreyfus was far more exacting than he was. As she turned the work in, Dreyfus intimidated Fay by asking, “Are you good?” Fay replied, “I think so,” and that was how she became the firm’s first woman attorney.4

Barney Dreyfus concentrated on criminal defense, constitutional law and civil rights. The third partner, Frank McTernan, was an earnest, New Deal enthusiast who started practice in the ’30s as a labor lawyer and expanded his practice to include civil rights law. By the time Fay started work, the firm’s first black lawyer had left and another associate, James Herndon, had taken his place. Herndon, a past employee of The San Francisco Chronicle, was politically connected in the black community, with many contacts who referred him personal injury work. Fay was impressed — she never expected to bring in clients herself. Marvin, in his own law practice had, by now, learned the same pragmatic lesson most Guild attorneys understood: “P-I cases pay the office expenses, and most political and criminal cases don’t.”5

At the firm, Charles Garry brought in the most revenue. Fay described the dynamics of that Leftist firm: “Charles is the heart, [Barney Dreyfus] is the brain of the human enterprise in which Frank McTernan supplies humility … and Herndon the young blood.”6 At the time, criminal defense and personal injury practice were considered combat zones for which women were presumptively unsuited. At day’s end, war stories were exchanged with free-flowing liquor. Gathering evidence in criminal cases sometimes included payoffs to cooperative police officers. That was how Charles Garry and Jack Berman had obtained copies of crucial police reports to help acquit Cal student Robert Meisenbach in the Black Friday case. This rough world, rife with illegal bribes, was not much different from Clarence Darrow’s day.

For a woman lawyer in the ’50s and ’60s attempting to parent small children, courtroom work was especially difficult. Garry had spent years developing his trial practice skills by working day and night and often slept in his office. Though he made time for a mistress, he rarely saw his long-suffering wife and had no children. Many women who could have easily handled law school in the ’50s opted instead for careers as legal secretaries because of the huge disparity in job opportunities. That included women already working at the Garry, Dreyfus firm when Fay was hired in 1961. The only one Fay met who wielded significant responsibility was the office manager. It was an open secret that she was also Barney Dreyfus’s mistress. While Fay was there, the office manager continually studied for the California Bar, ultimately passed it and left the firm.

At first, Fay was overwhelmed by juggling her parental responsibilities in Berkeley around her part-time job in San Francisco, despite its flexible hours. Fay dropped her one-and-a-half-year-old daughter and three-year-old-son at nursery school each morning. Each afternoon, she would rush from work to pick up Neal and Oriane, shop, make dinner and put them to bed. She told an interviewer years later, “My goal was to get through each day and not go to the looney bin.”7 Both Ann Fagan Ginger and Doris “Dobby” Brin Walker, prominent Old Leftists in the San Francisco Lawyers Guild, also raised children for a period of time as single parents. Fifty years later, with a shudder, Ann vividly recalled going it alone after her divorce from labor historian Ray Ginger. “As a single parent for five years, I know how you do it. You go crazy. Doris would say the same thing: ‘Who in the Hell’s got time to have friends?’” Ann quickly added, “I mean that’s a terrible fact. But to be a woman lawyer in this era that we’ve lived through and to be a political lawyer [is a recipe for chaos].”

Source: FBI file on Fay Stender, Vol. 1

The FBI began tracking Fay Stender’s civil rights activities after she joined Charles Garry’s law firm.

Attempting to meet her children’s needs on top of racing back and forth to work often filled Fay with a sense of hopelessness. She started seeing a psychiatrist again, but quit when it became too costly. Her life seemed to reach bottom in the fall of 1961. Fay had sneaked a visit to Stanley Moore in New York a few years earlier and still corresponded with him. Over Christmas, Fay again saw Moore when he came to town to visit his family. She was still estranged from Marvin. Moore invited Fay to spend the next summer with him, but refused to consider another marriage and had no interest in raising children. Fay did not think she could survive another intense interlude with Stanley, only to be dropped at summer’s end.

Over New Year’s, Fay took a short vacation alone with Marvin to celebrate their wedding anniversary. Despite all their difficulties, she appreciated his ongoing commitment to both her and the children’s financial support. Marvin offered to give Fay money to resume analysis from funds he was about to receive from a family trust. By the spring of 1962, Fay was upbeat. She had just passed the milestone of her thirtieth birthday. She cut her hair to shoulder length, kept her nails painted with bright red polish and decided to buy a car. She felt like a new person and told Stanley Moore she never wanted to see him again. Fay and Marvin took the children on a family camping trip together. They postponed any thought of formal separation papers, though they still had no plans for reuniting.

By then, Fay’s work for the Garry, Dreyfus firm had evolved into a steady, half-time position. A side benefit was introduction into the inner circle of Garry’s Leftist friends Bob Treuhaft and his celebrity wife Jessica “Decca” Mitford. Almost a generation older than Fay, the Treuhafts made a strikingly odd couple. Bob was a thin, dark-haired Jew with a heavy Bronx accent. He had never made friends with any Gentile until he went to Harvard. Decca was tall and blue-eyed, a broad-boned brunette with an unmistakably upper crust enunciation.

The Treuhafts had been members of the American Communist Party from the mid-forties to 1958. Decca enjoyed being known as the defiant “red sheep” daughter of an ultraconservative British peer and his wife, Lord and Lady Redesdale. Both of her parents supported the German Nazi rise to power, as did one of Decca’s sisters, who joined Hitler’s inner circle.

The Oakland firm of Treuhaft and Edises had represented mostly black clientele since 1948, back when Fay was still in high school. In 1951, Senator McCarthy named Treuhaft one of the most subversive lawyers in America, which Bob and Decca considered high praise. When Fay joined the Garry firm, Decca and Bob were in the midst of exposing outrageous practices of the funeral industry. The American Way of Death became a best-seller. The book prompted Congressional hearings into the unconscionable fees the funeral industry charged unsophisticated mourners unprepared to resist aggressive sales pitches while still mired in grief over a lost family member.

Fay would later learn that Bob Treuhaft was one of Huey Newton’s childhood heroes. Treuhaft had gained instant renown in the black community for winning an improbable appeal in 1951 of a murder conviction. The defendant was a local black shoeshine boy named Jerry Newson, whom police had beaten to obtain a confession that Newson later repudiated. Even while still in elementary school, Huey Newton and his friends had appreciated the significance of that historic case.

In the early ’70s, Fay and Decca would work closely together on prison reform. What impressed Fay back in 1961 was that Decca and Bob knew anyone who was anyone nationally in radical politics; the couple threw the best Leftist parties around. When she joined the Garry firm, Fay made the “A” list of invitees. Decca did not mind when Fay brought Neal and Oriane along.

Jessica (“Decca”) Mitford Treuhaft (1917–1996)

Source: Everett Collection Historical / Alamy Stock Photo

Bob Treuhaft (1912–2001)

Souce: Spartacus educational http://spartacus-educational.com/USAtreuhaft.htm

In 1951, Senator Eugene McCarthy named Bob Treuhaft one of the most subversive lawyers in America. Bob and his wife Decca were delighted. When Fay joined Charles Garry’s firm, she made the “A” list to the Treuhafts’ famous Leftist parties. By the mid-1970s, Fay would stop speaking to Bob, and Decca would describe Fay as her “frenemy.” (Both photos circa early ’60s.)

Being at the Garry firm also placed Fay at the center of Leftist efforts to change the status quo. By 1961, Decca had already published her first memoir, Daughters and Rebels. In it, Decca famously observed that “You may not be able to change the world, but at least you can embarrass the guilty.”8 By then, Garry and Dreyfus had both achieved widespread recognition as criminal defense lawyers for getting psychiatric evidence admitted to avoid the death penalty. The partial defense of diminished capacity was afterward known in California as the Wells-Gorshen rule for the last names of their clients in two landmark cases. Expert testimony was now permitted to show that a homicide might have resulted from uncontrollable psychological impulses. Garry credited the Wells-Gorshen rule with being “an invaluable lever in the plea-bargaining process,” dramatically reducing the number of executions for what would otherwise have been capital crimes.9 “Sleepy Nick” Gorshen only served three years of his sentence before he was paroled and went back to work as a longshoreman. When Fay started work for the firm, Garry was still working periodically to secure Bob Wells’ release, a long-term project finally realized in 1974.

Fay started out by assisting the partners with research and drafting briefs for personal injury and criminal matters. The Garry firm handled personal injury cases the same way as did other lawyers in the field, on a fee contingent on whether they won or settled a case. The firm made substantially less money from its personal injury practice than many other lawyers because their black clientele routinely received smaller jury awards than whites with similar injuries. Newspapermen covering Oakland reflected similar prejudice. Warren Hinckle, who became the editor of the Leftist Ramparts magazine in the late ’60s, later recalled the guidelines followed when he had started out as a cub reporter. The newsworthiness of traffic deaths depended on the race of the victim. Working for a leading San Francisco daily, Hinckle was taught: “No niggers after 11 p.m. on weekdays, 9 p.m. on Saturdays (as the Sunday paper went to press early).”10

Fay handled the appeal from one particularly discriminatory verdict. She accused the defense attorney of appealing to racism for telling the jury that “Negroes have a tendency to exaggerate their complaints, to have poor memories, and to be unable to remember events.” But Charles Garry had failed to ensure that the court reporter typed up the closing arguments — a lesson for Fay for the future to make sure that every significant misstep by opposing counsel was captured on the record.

The partners soon realized that no matter how routine the assignment, Fay would exhaust all possible avenues, thinking both inside and outside the box. Garry liked her unrelenting approach. Fay found a sharp contrast in working with Barney Dreyfus. Unlike Garry, Dreyfus demanded disciplined writing and never simply signed his name to an associate’s draft. She later reflected that Dreyfus was “not the easiest type of person for a woman to work with in sexist America. Despite his name, his identity as Jewish is virtually non-existent. We are representatives of completely differing styles of being, personality, expression, consciousness. There was a lot of pain (for me—whether for him, I never was sure).”

Dreyfus held doors open for women and displayed great chivalry, but in meetings either ignored women altogether or behaved in a patronizing manner, often admonishing the object of his dismay with “Now, now, little girl.” Yet Fay grew to admire Dreyfus. She credited him with “charm, manners, elegance, wit, elitism, anachronistic integrity, enigma; one would not mistake another for him.” After years of his tutelage, Fay conceded that “He taught me more than anyone else about the practice of law. ‘It is,’ he said, ‘the meticulous attention to detail.’ Truer words few people have spoken.”11

To Fay’s relief, as the firm’s business expanded, she retained a permanent part-time position. Among the appeals she handled, Fay found she particularly enjoyed wrongful termination cases even though she lost a major case about the scope of the Regents’ authority to fire university staff. It would be cited again and again over the years by lawyers on the other side. Still, administrative appeals were the type of “bread and butter” cases Fay would turn back to in the ’70s after she no longer represented criminal defendants.

In 1962, the partnership moved to more spacious quarters and added a new associate, Don Kerson, in the office next to Fay’s. Though the two did not interact much, Don always knew when she was in her office because the walls shook whenever she typed. Don could also hear her yelling at hospital administrators over the telephone as she pursued her ICEA mission to transform delivery room policies.

It was not long before the partners decided it was time to let Don and Fay try a criminal case together to gain trial experience. The case was a “dog” — one the partners expected to lose. People v. One 1954 Ford Station Wagon involved a car confiscated by police after they claimed to have found a marijuana cigarette in it. Don could not dissuade Fay from challenging the routine test the police used for analyzing the presence of marijuana. Watching Fay emphatically wave her hands in court to underscore her arguments, Don could see the judge was unimpressed. Don was not surprised they lost.

* * *

Fay’s niche largely remained brief-writing for Garry and Dreyfus as she shuttled her children to school and extracurricular activities, commuted across the Bay Bridge and spent much of her time at the firm scurrying between its law library and her office. Still separated in the spring of 1963, Fay told hardly anyone that she had rekindled a romance with her former fiancé, Bob Richter. After Fay rejected him following his release from prison in 1952, Bob had earned his degree at Reed and married another Reed student before moving to Iowa and obtaining an M.A.

During Fay’s first semester of law school in 1953, Bob had brought his new wife to visit Fay in Chicago. Fay did not see Bob again for almost another decade, while Bob volunteered for civil service and received a pardon from President Eisenhower, erasing his conviction. By the time Fay saw him again, Bob’s career had begun to take off. He had already assisted screenwriter Richard Maibaum and was now a producer and reporter for Oregon public television and radio. The New York Times also employed him as a part-time journalist.

Bob contacted Fay in the spring of 1963 and arranged to come down from Oregon for a weekend together. He was unhappy in his own marriage and knew that Fay remained separated from Marvin. Fay had Neal and Oriane that weekend and brought them along when she and Bob stayed at a beachside motel south of San Francisco. Unlike Stanley Moore, Bob enjoyed young children. He relished catching up with Fay as they walked along in the sunset with Neal on his shoulders and Oriane in Fay’s arms. Even more, Bob would cherish the memory of putting the two preschoolers to bed in an adjacent room so he and Fay could spend a torrid night together.

From then on, Bob visited Fay whenever he had business in California — once every month or two — until she reunited with Marvin in 1965. When Fay and Marvin separated again later on in their marriage, Bob and Fay discreetly revived their long-distance affair. At one point he proposed to her, but Fay resisted. They kept up sporadic trysts over an eighteen-year period, ending in 1979 shortly before she was wounded.

While separated from Marvin in the ’60s, Fay saw her old law school friend Alice Wirth Gray and her husband Gary fairly often. Fay confided to Alice that she and Marvin were planning to divorce and asked Alice to play matchmaker. Fay’s fantasy was someone with whom she could play “The Trout Quintet” arranged to be performed as a duet on a piano and string instrument. The challenging Schubert composition included a famous fourth movement that evoked the image of a trout skimming the surface of a river. Alice coincidentally knew an academic psychiatrist who was single, an opera buff and amateur violinist. He had also been looking for someone to accompany him on the piano playing “The Trout” transcribed for two musicians.

Alice excitedly told Fay about her psychiatrist friend and invited both to dinner at the Grays’ home to perform the piece for a few friends. After the performance ended, Fay stomped into the kitchen to speak with Alice privately. Alice assumed she was upset that the psychiatrist was not as accomplished on the violin as Fay was at the piano. No, an irate Fay turned to Alice and exclaimed, “You didn’t tell me he was a midget!”

In addition to seeing Bob Richter, Fay managed to renew her sado-masochistic relationship with Stanley Moore. He had finished his second book, Three Tactics, and was on the brink of accepting a professorship in philosophy at U.C. San Diego. Contradictory impulses never gave Fay much pause. As Neal and Oriane grew, Fay also felt a surge of religious identity that she had abandoned under Stanley Moore’s influence. Much to Marvin’s surprise, Fay determined to raise her children celebrating Jewish holidays.

Marvin had never exhibited an interest in following his family’s religious traditions, but Sam Abrahams always presided over a Passover Seder with a large family gathering that Fay and Lisie usually attended. Every year, the Abrahams extended family focused on the Exodus of Jews from Egypt and celebrated their freedom from bondage. Fay felt that her children would benefit from exposure to the Torah’s ideals of justice and freedom. She even sent Neal to an orthodox day school for a short time, with Marvin’s acquiescence.

Fay’s old friend Betty Lee (now going by her given name Ying and married name Kelley) came on a now rare visit to Fay’s home with her own five-year-old and was astonished that Fay had a menorah and toy dreidl. “What are you doing?” she asked. “I want the children to know their heritage,” Ying recalled Fay replying. Yet Fay shocked her parents just as much by taking Neal and Oriane and Lisie’s two young daughters, Linda and baby Lora, on an Orthodox Christian Easter egg hunt.

In the early ’60s, besides renewing a long-distance relationship with Bob Richter, Fay dated several local men. These included her old friend Stan Seidner, the perennial psychology graduate student and classical cellist. Stan now spent most days among the lost souls and panhandlers on Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue. At the end of November 1963, Fay’s high school friend Hilde stayed a few days with Fay after Hilde’s own marriage had begun to crumble. In her short stay in Fay’s untidy apartment, Hilde met the unimpressive Stan and a couple of other men Fay was then seeing. They seemed to drop by Fay’s apartment at will.

Finding a rare moment for some private conversation, Hilde and Fay exchanged bitter observations of the inappropriate reactions of the men they were with as a national paralysis set in on the somber November day of President Kennedy’s assassination. Hilde’s husband had taken advantage of the halt in ordinary activity to sell his car. When the shocking news hit the airwaves, Fay had been shepherding a famous philosopher visiting the Bay Area. He wanted to take her to bed. “Men!” they said. But Hilde had been disconcerted by Fay’s chaotic approach to life as a single mother and viewed it as a cautionary tale.

Fay herself had grown unhappy with her current situation and longed for more stability. She and Marvin remained on cordial terms as they drifted toward divorce. Yet the idea of being totally on her own with two children and no husband filled Fay with increasing anxiety. As much as she disdained her sister’s safe life in the suburbs, Fay had her own traditionalist streak that counted on Marvin for security. The family still took camping trips together and socialized among the same circle of Leftist friends. In their spare time, both Fay and Marvin became increasingly active among friends supporting bold civil rights projects. Over the next two years Fay sought to entice Marvin to give their marriage another try. The excitement they both felt as they launched themselves into Movement activity was a powerful catalyst.

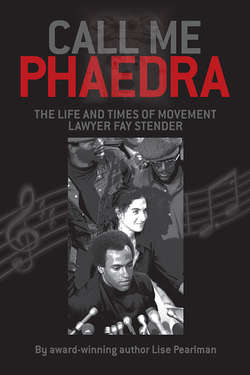

Source: San Francisco Public Library History Center, Stephen Vincent, “Tracy Sims and the Civil Rights Protests,” 1964.

Nineteen-year-old Tracy Sims (left) was one of the leaders of the protesters arrested in the spring of 1964 for picketing discriminatory hiring practices at the Sheraton Palace and Auto Row in San Francisco. Lead defense lawyer Beverly Axelrod stands center; co-counsel Mal Burnstein stands left behind Sims; defense team member Patrick Hallinan is to Axelrod’s right. The arrests resulted in the longest municipal court jury trial in the city’s history and almost bankrupted Axelrod. This ordeal was fresh in both Burnstein’s and Axelrod’s minds in the summer of 1965 when they opted to waive a jury for the trial of 155 representative Free Speech Movement protesters arrested in December of 1964 for occupying U.C. Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza –- a decision the civil rights lawyers later vowed never to repeat in a political trial.