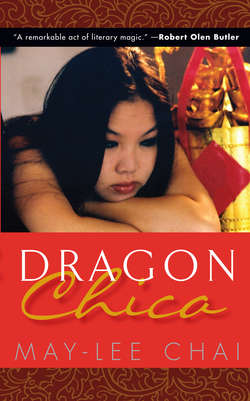

Читать книгу Dragon Chica - Mai-lee Chai - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 5 A Million Shades of Black

ОглавлениеAuntie apologized that she had not been able to greet her sister properly, explaining that she’d been resting upstairs. There was a little apartment there. Originally she and Uncle had thought about renting it out for extra income, but then Auntie had found it useful for her bad days, when she felt too tired to work, when her head hurt, when she grew dizzy, when her heart stopped beating.

“Your heart,” Ma gasped.

Auntie shook her head.

“You should wake me,” she said to the old man who was now unquestionably Uncle. She scowled. “This is my sister!” She took Ma’s hand in hers as they sat together in a booth. “My baby sister!”

“Your face,” Ma cooed, stroking Auntie’s darkened flesh, where her skin had been burnt, the waxy pale side where the scar tissue had formed and the raised purple scar that ran down her cheek to her throat. “Your beautiful face,” Ma whispered.

Auntie unbuttoned the cuff of her blouse and slowly rolled the cloth up her arm to her elbow, revealing the skin beneath, the crisscross of scars, her flesh patterned like the weave of an elaborate basket.

Ma cried to see her arm. She shook her head, back and forth, back and forth.

“The Red Cross doctor, he said to me, ‘What a lucky woman! It’s a miracle! You kept the arm with cuts like that!’ He said I was lucky because he didn’t see what happened to my son. What happened to my baby.” Auntie shook her head as though she could dislodge the memory, tip it out the side of her head like water.

Ma stroked the inside of Auntie’s arm, her fingers fluttering above the skin, touching down here and there, like nervous moths hovering around the flame of a candle.

They sat in a back booth, while Uncle brought them tea, and Auntie told us how she’d walked through a mine field, carrying her youngest son in her arms, her middle boy following behind her. The oldest son was sent away to a work camp at the beginning of the war, and she never saw him again.

Auntie waited too long to leave with her sons, she said. The soldiers watched her night and day. She should have left sooner, but she was afraid. Too many people like her, city people, had been beaten to death before her eyes. Auntie was afraid. She tried to work in the fields, she tried to obey, but then a woman she knew, a woman who had a run a restaurant in Phnom Penh, fell while planting rice and broke her ankle, and the soldiers then convened a meeting, forcing everyone in the village to watch as they beat the woman to death with shovels. An example, they said, of what happened to lazy city people who didn’t know how to plant rice.

Auntie ran away with her sons that night, while the soldiers slept. But by now she was too weak. She was too tired from the work, the worry, the fear, the lack of food. She should have carried both boys. She should have carried them the whole way, she said, but she couldn’t think. She made the older boy walk. How old was he when she thought he was old enough to walk by himself? Was he seven? Eight? But he was so thin. In her memories he seemed even younger. She should have carried them both, she told us, over and over, shaking her head. She should have found a way.

“We were walking in the fields, in the dead fields where nothing grew anymore. The fields with bones. We were walking in the night. I was afraid. The moon was bright this night, the kind of night where soldiers can see who is running away. I carried my youngest son but made the older boy walk behind me. I hadn’t slept for weeks. Then my boy saw something. Something shining in the moonlight. ‘Look!’ he calls to me, and his hand slips from mine, like water, and he is running away from me, he is running towards the shiny metal thing. What does a boy know? He was so close. I should have run after him, but I was afraid and then I heard the click, like bone against bone. The click, and then the bomb. I fell to the ground. I found his head but not his body. He was so close when the bomb went off beneath him, my face was cut by the metal, my arm was burned. What a lucky woman, the doctor said. So lucky.”

Auntie wanted to lie there forever. She wanted to lie down on the ground and die but her youngest son was still alive. When the bomb exploded, and knocked her to the ground, she fell over the youngest son’s body, and he was not hurt. Maybe she should have died then, Auntie would think later. Maybe it would have been better. But she got up and started walking.

She left her eight-year-old son’s body on the ground, in pieces, and walked away. She carried her youngest son in her arms. He was three years old, but so light, like a baby. At the time his lightness didn’t frighten her; instead she was grateful because she needed to carry him the whole way. He had a fever. She could feel the heat against her skin, like fire. At first he cried and she was scared the soldiers would hear them. After he stopped crying, she was relieved.

She was carrying his body when she reached the border. She thought, We are saved! She thought, I have done something right. I have saved my youngest son. She thought the doctors could do something. Auntie had great faith in Western doctors. But they took his body away and wouldn’t give it back to her. And then the doctor looked at her face and he told her what a lucky woman she was to be alive. What a miracle it was.

She didn’t kill herself then because she didn’t know what had happened to her husband or to her oldest son or her daughter. Not that she would ever be any use to them. She understood that. She said she was a failure as a mother. “I stayed alive so that I could tell my husband if I ever saw him again how his children died. I am not a mother. I am not anything.”

Ma held Auntie’s hands as they sat in the back of the Palace, the sun falling lower in the sky, the sky growing darker, shadows slipping from the fields and seeping into town, inching across the parking lot, surrounding the Palace like an inky tide.

I squatted on the floor by Sourdi, listening, my arms around my ankles, my forehead resting on my knees.

After Auntie finished speaking, Ma was quiet for some time. All I could hear was the soup stock bubbling on the stove and the electric fans whirring back and forth in the kitchen, circulating the scent of garlic and mint and our sweat.

When Ma finally spoke, she did not tell Auntie the story of her own escape, of our escape, or of my father’s death. Instead she took hold of her older sister’s elbow with one hand so tightly that her knuckles shone pearl-white through her skin, as she said over and over, “Your oldest son, he must be alive, he must be alive, he must be alive.”

Ma didn’t mention the daughter. I took that to mean she figured she had died or been married off to a soldier at a young age, which was almost the same as dead. That used to happen, young girls married off to strange men who took them to different work camps and their families never saw them again. We left the village the soldiers had assigned us to before that could happen to Sourdi. I squeezed my sister’s hand, grateful she’d not been married off to a soldier.

Uncle stayed in the kitchen, entertaining the little kids the whole time Auntie talked to Ma. He had them sit around the prep table on stools, rolling silverware tightly into the white cloth dinner napkins. After an hour, they grew bored, and he sent them outside to the parking lot to play. When I crept to the door to see what he was doing, I saw him sitting with his head in his hands, before a huge mound of napkin rolls, staring at them as though they were a pile of broken bones.

That night, in the house that Auntie and Uncle rented on the outskirts of town, I could not sleep as I lay next to Sourdi on the floor of our bedroom. The wind blew so fiercely through the open windows, with a sound like a woman wailing. The floorboards creaked, the pipes in the walls hissed, the whole house seemed to sway.

The house was big and tall with many rooms that Auntie and Uncle had planned to rent out, but now that we were here, they were ours. I had never been in a house so large. I thought of my mother lying alone in her bedroom downstairs. “Do you think Ma’s lonely?” I asked Sourdi, but my sister didn’t answer me, and instead rolled onto her side, pulling her pillow over her head.

The fields around the house sounded like the ocean, the way the wind swept through the corn, with a shush-shush sound, like the surf creeping up the beach. When I closed my eyes, I could hear the waves lapping at the edges of the room, where the darkness touched the hem of my sheet.

When the moon had risen just high enough to escape the branches of the box elder tree in the middle of the lawn, the bedroom filled with a clear, white light. I got up then and waded through the moonlight to the window. I could see the cornfields illuminated as though by flame. The fields flickered with a million shifting shades of black as the corn rippled in the wind. As far as I could see, the earth was moving, swaying, rocking. I felt as though I were in the hold of a large ship, adrift in the middle of the sea, waves stretching darkly to the horizon.

“Sourdi,” I whispered, but my sister had fallen asleep.