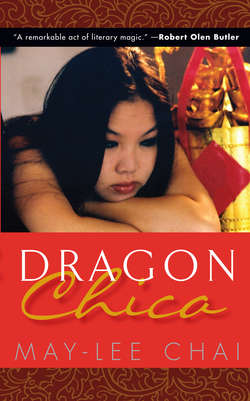

Читать книгу Dragon Chica - Mai-lee Chai - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 6 Father Dream

ОглавлениеThat night, I dreamed that our father died.

His breathing was labored, whistling from his lungs, phlegmy and thick. He had been breathing like that for days, and then in the middle of the night, he spat the last of his breath from his body.

I alone was awake, lying beside Sourdi on our bedrolls on the floor. We were living in the village, in the house on wooden stilts, beside the brown river. I listened intently, waiting for Pa’s next breath. His breathing had slowed, taken on a watery sound. Because I was hungry, I could stay awake all night. Sourdi slept soundly because she had to work in the fields with the older girls and the women. I watched the water buffalo with the other little children; we were not old enough to plant rice or to dig holes or to carry heavy loads. Not yet, but soon.

I lay awake, wishing Pa would breathe again. I had grown accustomed to the raspy sound. It broke the stillness of the long black night. Without it, my ears sought out other sounds, the snorting of the pig that lived beneath the house, the footsteps of the soldiers who stood guard all night in the village, the distant cry of a monkey. Such noises made my heart beat faster, made me think of the dead spirits that roamed through the fields at night, looking to cause harm. The dead were restless, the old woman who lived next to us had explained, because they had died unhappy deaths. No one had prayed for their souls, offered incense at the pagoda, hired monks to chant at their bedsides. They died alone and afraid. They could not be reborn yet; their souls had lost their way to the underworld without the prayers to guide them. They had lost their bodies and were looking for new ones. If you didn’t look out, she said, they might snatch yours!

When the old woman talked like this, I wanted to clap my hands over my ears and close my eyes tight, to hide from the terrible things she talked about. But we weren’t allowed to do such things, hide from evil spirits, because the soldiers said it was wrong, it was not true. At least, the older soldiers said this; the young ones were just as scared of spirits as we were, but they were not allowed to contradict the leaders.

In my dream, the old woman was sitting next to me, the night our father died. She was squatting just outside my mosquito net, her white eyes open and staring blankly in the dark. She was humming, a low animal-like song, singing our father’s soul to sleep.

I wanted to reach out and touch her. I wanted to make her stop. But my limbs felt heavy, immobile. I lay on the bedroll, watching her, wishing Sourdi would wake up, but Sourdi slept on and on, and the old woman began to sing louder.

She was the oldest woman in the village. Her hair was mostly silver and was so thin in places, you could see her brown, shiny scalp. Her few remaining teeth were stained red-black from chewing betel, and her eyes were cloudy gray, not black like eyes were supposed to be. Some of the boys called her “Witch” but not me, not to her wizened face anyway. Ma said I had to be kind to the old woman. Ma made me bring her cups of water during the day, when it was hottest and the other women were still in the field. The Witch was too old to do such work so she did laundry for the others, sitting on the edge of the river, beating clothes against the rocks there.

When I brought her some of the water Ma boiled and kept in a pot in our house, she’d drink it, wiping her mouth on the back of her hand, then she’d smile at me with her red-black teeth.

The Witch had come to our house a few days before Pa died. Ma had wanted her to listen to his chest. The Witch said the spirits that controlled his head were out of balance. She said we needed to gather a special kind of bark from the trees in the forest and to boil it into a tea for Pa to drink. But Ma had not been able to leave the camp that night or the next. On the third night, Ma had disappeared for several hours, when everyone else was asleep and I lay awake, listening. She had returned just as the sun was rising, the pig was waking and the soldiers began to walk in twos and threes once again after settling down for the night. The soldiers were not supposed to sleep at night, but sometimes they did. If I pressed my ear to the cracks in the floor, I could hear their snores. Ma returned to her bedroll next to Pa’s, pulling her mosquito net closed. She was pretending to sleep, so that the others would think she had lain there just like that all night long, but I could hear her breaths, too fast and shallow. I lay still, and she did not know that I had seen her return.

That morning, Ma boiled the bark tea for Pa, and the whole house smelled like rotting fungus and river water, the tea created such thick clouds. Ma was afraid the soldiers would smell it and then they would guess that she had left the village in the night, ventured past the fields and into the forest, where we were forbidden to walk. But the wind was strong and it blew the steam across the river, where the scent was lost among the odors of the fish and the mud and the reeds.

Pa couldn’t drink the tea, however, even though Sourdi held his head while Ma poured the liquid down his throat. He coughed and choked and then vomited the green liquid back up onto his chest. Ma cried then. I saw her wipe her tears on the back of her hand quickly, drying her face just as fast as her tears could flow, so that when she left to work in the field, the soldiers would not see that she had cried.

In my dream, I was watching the Witch sing Pa’s soul to sleep when he stopped breathing.

All at once, the wind returned, rushing through the reeds beside the river, causing silver fish to leap from the waves. I heard them splashing. I hoped the wind would carry Pa’s soul far away from our village, away from the soldiers, someplace safe.

Because the wind had returned, the Witch stopped her song. Instead she threw her head back and howled like an animal. Her mouth fell open, wide as a python’s about to devour its prey.

I woke up screaming.

Sourdi put her arms around me, telling me it was just a dream, just a nightmare, I should go back to sleep.

We were lying on the air mattress in our new bedroom in Auntie and Uncle’s big house.

I cried. The wind rushing through the cornfields outside sounded like the witch’s singing.

“I can’t breathe,” I whispered to Sourdi. “There’s no air.”

Sourdi told me to ssssh. She made her voice soft and low, she blew against my neck, she turned into the wind that used to blow through the open windows of the house on wooden stilts by the brown river in the village where we lived during the war.

She made her voice softer still, until it was a song, a song about a shepherd boy and a weaving girl who lived among the stars in the sky. They were in love but they lived too far away, separated by galaxies, so they could see each other only once a year. It was a sad song, but not a frightening song, not a witch’s song, but a young woman’s love song.

Sourdi’s voice grew softer, just a tickle of breath on my skin, and I could almost sleep again.

“Ssssh,” she whispered, “it’s just a dream, just a dream.” Her voice disappeared into my ear.

My eyelids grew too heavy, they shut across my eyes, and I was almost asleep again.

“Just a dream...”

I smiled, sleepy-like, just for her. But she was wrong. It was a memory.