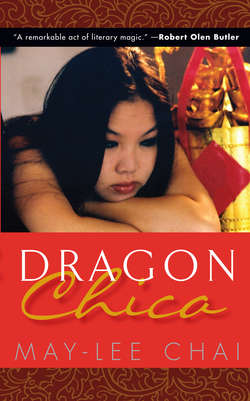

Читать книгу Dragon Chica - Mai-lee Chai - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 8 Auntie

ОглавлениеAuntie, I soon discovered, liked to complain about unusual things.

“The sky is too large. I feel I am being swallowed alive.” She waved her hand airily in the direction of the cornfields and the soybean fields and the blue dome of the sky that seemed to stretch all the way to Minnesota.

“And the wind here is too fierce. It is treacherous and uncivilized.” Auntie drew her arms across her chest then and shivered.

When Auntie talked like this, Ma laughed. “You haven’t changed at all,” she said cheerfully as though saying something with enough confidence would make it so.

Auntie turned from the glass of the front door of the Palace where she was surveying the empty parking lot. “Time to practice our English.” And she turned on the television set Uncle had set up behind the counter next to the soda machine and the metal cabinets for the plates. “You must all lose your Texas accents or none of the people here will ever understand you, Sister Dear.”

Then Auntie sat down on one of the swivel stools to watch her favorite soap opera, which consisted of nothing but people getting married and then divorced then married again, as far as I could tell.

While Auntie watched TV, mouthing the lines along with the actors, Ma cleaned the Palace, scrubbing everything in sight, the tables and the counters, the metal cabinets, the soda pop dispenser, the cigarette machine by the front door. She joked about the customers and the strange ways they seasoned the food, adding soy sauce to their rice, salt to their vegetables, sugar to their tea.

Auntie didn’t know how to cook or clean, of course, not when she’d always had servants for such matters, and so Ma didn’t expect her to help.

“Nea, take the children outside to play. I can’t have them running around when I’m busy,” Ma commanded as she mopped the floor. “Sourdi can help me inside.”

I was only too happy to obey. It was hot outdoors, but the cold inside the Palace frightened me.

I immediately installed myself in the shade behind one of the large green dumpsters where I could read one of my favorite books, a dog-eared copy of The Martian Chronicles that I’d borrowed from the public library in East Dallas before we left. Reading about the adventures of astronauts on Mars appealed to me in a way that watching my younger brother and sisters throw scraps of garbage to the seagulls did not. It’s true; by now, even the once miraculous appearance of the gulls no longer thrilled me.

Time passed while I explored an empty Martian town, eerily reminiscent of my hometown on Earth, but empty and ancient.

“Ugh! Filthy birds!” Sourdi said, emerging from the kitchen with a dun-brown Hefty bag. She tossed it into the dumpster where it split, exposing the chicken bones and cabbage hearts and tin cans inside.

She swatted the air as the birds swooped closer for inspection.

Sourdi wiped the sweat beading across her forehead with the back of her hand. Her skin was moist, her pink T-shirt ringed with dark bands beneath her armpits. Her black hair was pulled back into a ponytail off her neck, but her face was red all the same. She looked miserable. Because she was almost sixteen, she couldn’t sit in the shade and hide from the adults like me, but had to keep busy all the time.

“Who all wants to help me peel the shrimps?” she asked hopefully.

I ducked my head back into my book. They were not just shrimp, I knew, but in fact the Special of the Day, $8.95, Imperial Prawns. They didn’t entail peeling so much as ripping their long, black spinal columns from their fat, spongy bodies.

“Not me!” Sam squeaked up immediately.

“Not me!” the twins repeated.

“Come on, y’all like to eat ‘em,” Sourdi cajoled us.

“We do not,” Maly said, which was true enough. The twins had come to like only the most American of foods, cheese that came wrapped in plastic, soups that came out of cans, meat that sat between buns. They constantly astounded us with their strange eating habits.

“I only like them if they’re cooked,” Sam said.

Sourdi sighed. More sweat was gathering across her forehead. She blotted her face daintily now with the edge of a tissue pulled from her pocket. She was having trouble with acne and no longer indiscriminately wiped her face on the hem of her T-shirt like the rest of us.

“Don’t any of y’all want to help me?”

“I am helping,” I insisted, pointing to our siblings. I tucked my book beneath my legs surreptitiously.

“You monkeys,” Sourdi said, but then she smiled, unable to hold a grudge. My older sister had been cursed with a sweet disposition. She dabbed the sides of her nose carefully with her tissue one last time then went back inside the steamy kitchen.

We were all relieved that she had not made us go back inside, especially me, although I felt guilty admitting as much. Sourdi reminded us of what was to come when we were adults, or at least old enough to be considered an adult by our mother. I didn’t look forward to the prospect.

“We’re gonna show you how to pray to the Holy Ghost,” Maly announced next as I tried to return to my book. My twin sisters now jumped up and, standing side-by-side, rolled their eyes back into their heads so that only the whites showed. Then holding their arms outstretched, palms upwards, they began to make crazy noises, looping nonsense syllables that rose up and down in pitch. Their eyelids fluttered rapidly over the whites of their eyeballs.

“Cool!” Sam exclaimed.

“Yo, that’s whack,” I said. “Y’all act like that, the police gonna come lock you up like you on some kinda drugs.” I hoped I could shame my sisters back into normalcy. The last time I’d seen anything like this, it was in a movie, and the little girl’s head had started to spin around her neck like a top.

“Ubba ubba ubba,” my sisters moaned, their voices rising. They flailed their arms in unison.

“You’re acting like freaks, don’t you get that?” I forced my voice to sound calm, a little bored even. Sam, switching allegiances now, giggled.

My sisters’ eyes flapped open. “Y’all don’t know nothin’! That’s how the Holy Ghost is s’posed to talk!” Maly announced indignantly.

We were all arguing like this about nothing when the boys came. Three of them, on bicycles. They circled at first from afar, in large swooping arcs, then suddenly one of them yelled, “Japs!” and they started throwing rocks.

I bent over the twins, trying to protect them, while I shouted, “Help! Help!” as if someone could hear me. But the cook had the radio on, and there weren’t any customers pulling up, so of course no one came to our rescue. I felt a sharp stone strike my head, and for a second, I couldn’t see a thing for the pain, as though a knife had been inserted into my temple. I was so surprised, I couldn’t remember how to breathe.

And then I was angry.

The boys had stopped circling to watch me as I held my head with my hand. They were standing over their bicycles, doubled over laughing.

“Get behind the dumpster,” I hissed to the girls and Sam, and then quickly I gathered up as many of the boys’ stones as I could find on the asphalt.

“Hey, pendejos!” I shouted. While the boys pointed and laughed at me in an exaggerated fashion that made them seem simple, I grabbed another rock and another. I saw clearly that the boys were at a disadvantage. They couldn’t ride their bikes if they had to stop and pick up more ammunition, and they had run out. “Hey, your mother suck the dick!” I shouted in English. This elicited a satisfying gasp. Then I took aim and smashed one of the boys in the face—a scrawny kid with orange hair and skin pale as a toadstool. He clutched his nose with both hands, blood gushing through his fingers. Then he jumped back on his bike and rode away.

The remaining two boys called after their friend, but he didn’t turn back. The boys hopped off their bikes and set them up like a shield while they scoured the parking lot for ammo. They shouted, “You eat dogs!” and “Go back to Japan!” but their momentum was clearly lost. I lobbed their rocks back at them, and then trash from the dumpster: chicken carcasses, fruit cocktail cans, beer bottles that shattered on the metal spokes of their wheels.

Even Sam and the girls joined in, hurling whatever they could find at the boys.

This time the cook could hear our racket. He came running out the back door with his bloody apron on, and the boys looked shocked, then jumped back on their bikes and took off, pedaling as fast as their legs could manage across the parking lot and down the street.

All in all, I considered the fight a success. I’d been hit a couple times, to be sure, and I could tell that I’d have a shiner for a couple weeks to prove it, but the boys had fled, not us.

Auntie, however, was horrified. She’d watched the whole ugly spectacle unfold from the windows of the dining room: the circling hooligans, my cowering siblings, and me throwing rocks in public, in the parking lot, for everyone in the world to see.

“Just like a street boy!” Auntie said, her voice rising and crashing in indignant waves. “Just like a hooligan! Nea acts like a girl who has had no mother! No mother at all!”

Sourdi was applying ice to my eye in the kitchen, and we both heard Auntie as she lectured Ma in the back of the dining room.

It was then that Auntie launched into a long speech detailing all my shortcomings: I was loud, demanding, bold; I had no grace; I clomped when I walked; I slouched when I stood; I mumbled when I spoke except when I cursed. I even fought with boys in public. I would be the ruin of my family. I was every wrong thing that America could do to a Cambodian girl.

I was hoping that Ma would defend me, that she would point out that I was brave and kind, that I got good grades in school, what a wonderful daughter, but Ma said nothing. Peeking through the kitchen door, I saw that Ma’s cheeks were flushed pink, her head bowed in apology. In shame.

I wanted to cry then, I wanted to shout, I wanted to break everything I could get my hands on, but I didn’t. Instead I stole one of the little knives from the cutting block in the kitchen and took it with me to the bathroom. I locked myself in the stall then and drew the blade lightly over the skin of my arm, just deep enough to draw a line of blood. Three times. After the wound began to throb, I didn’t feel like crying anymore.

That evening, I found myself alone with Ma, just the two of us to close the Palace.

I was setting the chairs atop the tables as Ma mopped the floor. We had the radio on, Tanya Tucker was singing about love gone wrong. The only stations we could get here played country music. I watched my mother out of the corner of my eye. She was more than twelve years younger than Auntie, but squinting, I could see a resemblance, in the way their nostrils flared, the width of their foreheads, the spacing of their eyes, and I could almost imagine Ma as an old woman, too, with snaky white hair, her body fragile and weak, with a heart that stopped beating in the middle of the day. She’d be sorry that she had been mean to me, when she was old and needed my help. But it would be too late. When I grew up, I was going to go far away, and I’d never come home again.

Ma stopped mopping to smoke. She took her lighter from her apron pocket and flicked it open with one smooth snap of her fingers, the blue flame jumping to life. Then she bent close to the fire, as though she meant to kiss it, her cigarette dangling from her lips. She opened one eye and stared at me.

“What’s wrong?”

I shrugged and pretended to go back to work, vigorously wiping the counter with a dishrag.

Ma closed her eye and took another drag off her cigarette. Blue smoke emerged from her nostrils. “What’s wrong?” she asked again.

“Auntie hates me.”

Ma opened both eyes. “Don’t be ridiculous. You’re her favorite.”

“That’s not true!” I cried out. “She absolutely hates me!” I couldn’t believe that Ma would lie to me like this, as though I were still a baby who would believe whatever she said like my brother or the twins, as I though I didn’t know anything. “I heard her talking to you today,” I said. “I know.”

Ma shook her head tiredly. She leaned her mop against the table and held her elbow in her right hand, her cigarette in her left. “You don’t know anything.” Ma brought her cigarette to her lips but then didn’t inhale. “It’s hard for my sister. She’s not like me. She lost everything in the war, her beauty, her children, her mind, everything.”

Ma stretched her arm between the chairs and placed her cigarette carefully on the edge of a fire-red ashtray. She picked up her mop. “Auntie likes you very much. That’s why she wants to teach you things.” Ma’s voice was firm, her tone final. It was the voice she used to end an argument. It was the voice that meant there was nothing to discuss.

“You wouldn’t let Auntie say those bad things about me if Pa were alive. He wouldn’t let her say those things. He loved me. He wasn’t like you.”

Ma pressed her lips together very tightly. Her eyes narrowed. I thought she might grow angry all at once, grab up her mop and strike something with it. I thought she might knock the chairs to the floor, she might shout or stamp her feet. She might turn her back to me and leave me in the dining room, refusing to say another word. But instead Ma exhaled slowly, blowing her breath through her teeth. “You remind my sister of the daughter she used to have. My sister likes you all right. It’s me she doesn’t approve of.”

Ma walked over to the window, dragging the mop with one hand, leaving a glistening trail behind her on the floor like a snail. She stared into the parking lot as though she could see something in the dark that deserved her full attention.

“You look like him. Your father, I mean,” Ma said, without looking at me. “You have his face. The same eyes. The same expressions. Sometimes I can’t stand to look at you.”

I put my hands to my face.

“I’m not like my sister. I married a poor man for love against my family’s wishes,” she said. “But my husband was a good man, and I know he’ll have a better life next time. I know this. We were never wealthy in our time together, so I don’t mind working now. It helps me to bear my memories.

“But for my sister, it’s different. She was so beautiful. Her face was like the moon, white and round. Perfect. Her beauty made her ambitious. She married a man above her rank, a man with a government position. She had money and all those servants. Because she was beautiful, she thought she was special. She thought she could have anything she wanted. People always treat a beautiful woman like that when she’s young, like the world will stop turning just for her.

“She never learned to bear things.”

Ma turned away from the window and looked at me with her dark, sad eyes. “I’m a lucky woman. My sister is the unlucky one. She isn’t used to that. When she sees you, you remind her of everything she’s lost. And everything I still have.”

Ma took one last puff from her cigarette before stubbing it out gently in an ashtray. She then picked up her mop with both hands. “Just try to be good. Just try a little harder. Okay?”

I nodded. She smiled, the edges of her lips pulling up quickly before dropping back down again, and then her face resumed its usual, neutral expression, the one that was neither sad nor happy.

I tried to obey my mother, I really did.

But as our days in the Palace turned into weeks, Auntie’s complaints only increased. She said her head hurt, as though the plates of her bones were drifting apart. And her heart beat funny—stopping, she claimed, for minutes at a time. She retreated to her apartment above the Palace, drawing the shades and the curtains, lying on her bed in the gloomy darkness, refusing to come down at all.

On these days, Ma sent me to check on Auntie with a tray of food and a pot of tea. Ma told me to be good and do as Auntie instructed. But sometimes Auntie said nothing at all, only staring at me, her eyes glittering in the dark, and sometimes she complained to me nonstop because nothing I did was ever right.

If I massaged her neck and back and arms, knotty as tree branches, she grimaced and grunted and said I might as well have been born a boy, all the use I was, I only made her bones ache more. When she wanted me to rub her back with spoons to promote healing, she yelped with pain and said I was trying to take the skin off her body. When she handed me her bottle of essential oil, which she wanted me to rub into her joints, I managed to spill the foul-smelling green liquid onto her sheets.

“In Cambodia,” she told me, clicking her tongue against the roof of her mouth, “children learned to take care of their parents.” She said as a girl, she had bathed her own mother every Buddhist New Year, in water that was filled with herbs and flowers, to ensure her mother’s longevity. She had done so willingly, and her mother had lived to be quite an old woman.

I was afraid then that Auntie would want me to bathe her next, so I said quickly, “Ma likes to take showers. She says modern life, that’s really living.”

Auntie fell silent for a long period, in which she merely glared at me with her dark, unblinking eyes, disappointed by my obtuseness. I pretended not to notice as I went about tidying up her apartment, dusting the television set and the end table, the reading lamp and its plastic-covered shade, and finally the tiny shrine to Buddha she had set up in the far corner, where the light never seemed to reach, not from her dimbulbed lamp, not from the sunlight seeping beneath the edges of her tightly drawn drapes. Still, the whole time I could feel her snaky eyes staring at my back, as though she were waiting for just the right moment to strike.