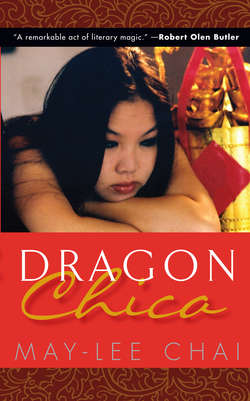

Читать книгу Dragon Chica - Mai-lee Chai - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 7 First Days in the Silver Palace

ОглавлениеThe Palace was beautiful. The six booths were covered in cherry red vinyl, a framed print of Angkor Wat in silhouette hung on the wall, a pink plastic chrysanthemum sprang from a bud vase on every table. Someone had even filled the vases with water to make the flowers seem more real. At the far end of the dining room, in the corner, was a little shrine with a pitched roof and curved eaves. A ceramic God of Wealth was seated within, behind a tiny urn for incense and a plate of miniature plastic peaches. The shrine plugged into the wall, and two red candles on either side of the pagoda glowed.

The spigots of the soda dispenser shone as did the table tops, the window glass, the tile floor. Everything was sparkling clean, brand new, ready for action.

“You should have seen it when we first arrived,” Uncle said, shaking his head. “Dirt everywhere. A big hole here.” He pointed to the ceiling. “Like a bomb had gone off. And the floors! Water everywhere.”

Our first day of work in the Family Business, while we waited with excitement for our customers, Uncle told us happy stories. The cook, for example. The cook wasn’t just some old Chinese guy down on his luck, willing to work anywhere, he was a bona fide chef, top tier. Back in the day—several decades earlier—he’d had his own restaurant that was so renowned, people lined up for hours just to peer in the windows at the other people eating inside. Reservations had to be made months in advance, and even then that wasn’t always early enough. In his youth, Uncle said, our Palace’s chef had apprenticed in a Shanghai gangster’s favorite restaurant in Phnom Penh. Oh, the extravagant banquets he’d prepared then! Hardened criminals rubbed elbows with ex-Kuomintang government officials, gun molls sat mere feet from fur-clad Tai Tai’s with their foreign businessmen husbands. A French priest had condemned the restaurant’s signature dish—a ginger-infused mitten crab clay pot stew—as sinful because its vapors encouraged the mixing of the races.

I squinted through the smoke in the kitchen at the skinny man, who sat in his undershirt on a stool, a cigarette dangling from his lips, while he flipped through his Chinese newspapers, ignoring the soup pot bubbling on the stove. I could almost imagine the young culinary prodigy Uncle was describing.

Uncle said he considered himself a lucky man to have found such a chef through the classified ads in Houston. A very lucky man indeed.

The cook was well-versed in the five major flavors— hot, sour, sweet, salty, bitter—and the eight regional styles. He could prepare snacks as well as banquet foods, meat dishes, cold dishes, dumplings, noodles, seafood, and vegetables, although, his eyesight not being what it once was, he could no longer be expected to carve melon rinds into the shapes of dragons or phoenixes or other mythical creatures. Of course, he had slowed in his old age, needed more time to prepare each dish, and could not always be trusted not to cut himself with the cleaver. Plus, he sometimes forgot the recipes, salting some dishes twice and leaving the centers of others uncooked. And once, he’d actually dropped the ashes of his cigarette into a bowl of curry. But Uncle said he had learned to work around these minor problems.

While we waited for customers, Uncle told us how everything was now in place for success. “Now that you are here,” he said to Ma with a smile, “our luck will certainly change for the better.”

When Uncle had first purchased the Palace, he’d seen the Native Americans walking on the sidewalks, their dark straight hair, their chiselled faces, and he thought to himself, with all these Chinese here, why didn’t they open a restaurant before?

Everything was perfect: no gangs, no competition for forty miles—the next nearest Chinese restaurant being in Sioux City, Iowa, and in the winter, forty miles was too far to drive just for a meal—no unexpected taxes, no bribe to this health inspector or that police officer who just happened to have ties to another restaurant. Everything was just as the Chamber of Commerce brochure had said. Small Town America at its best.

Except that no one had mentioned that in Small Town America people wouldn’t like our food.

At eleven-thirty on our first day of work in the Family Business, two men in black suits came in carrying a Bible. They ordered two iced teas and talked to Uncle about Jesus. When they departed at eleven-forty-seven, they left behind a pile of illustrated Bible stories for us on the end of the counter by the door.

At a quarter after twelve, a woman came in with three sweating, red-faced children. She explained the toilet at the laundromat was broken and could they use ours? Uncle said that they could. When they emerged from the restroom, Ma was waiting with menus. She opened one for the woman and placed it in her hands. The woman looked at it as though poisonous snakes might leap from its pages, then set it down carefully on the edge of a table and told Ma she had to “think about it” and they’d come back some other time, but she had to get back to the laundromat before someone stole their clothes from the dryer.

I watched them scurry across the parking lot, like mice fleeing a sleeping cat.

Three people came for a late lunch as all the other restaurants in town were closed between two and five and they were driving through town on their way north to the Black Hills. A couple came in for dinner, the man complaining that he’d lost a bet at work. They both ordered the same thing, fried rice and a Bud.

“It always takes time for a new business,” Uncle said, “time for people to get used to something new.”

He said the same thing every evening, while we sat around a back table after we’d locked all the doors and turned off the neon “OPEN” sign, and ate leftovers for dinner. In the beginning, Ma had made an effort to agree or at least to nod enthusiastically, but this night, the seventh night of our first week in the Family Business, she continued to chew her rice in silence, as Auntie did, every night, not bothering to lift her eyes from her bowl to watch her husband’s sweating face as he quoted from the inspirational books he checked out of the town library, two per week: “Genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration,” and “With the faith of a mustard seed, man can move mountains,” and “There is no hope for the satisfied man.”

While Uncle lectured, Auntie chewed her food carefully, spitting gristle and bone delicately into her napkin. When he finished, she rinsed her mouth out with tea, then picked her teeth with a wooden toothpick from the tabletop dispenser, carefully shielding her mouth with one hand.

However, this night, Uncle said something new.

He said that he was going to take another job, working in a Sizzler in Sioux City. “Just until business picks up,” he said. “Just for a little extra income.”

Auntie looked up at him for the first time in seven days. “And you expect me to run everything by myself while you’re gone?”

“Of course not,” Uncle said. “Your sister can help you. And all the children.” Ma did not look up from her rice bowl. She bent her head towards the table and scraped the last grains of rice from her bowl into her mouth. It was understood that we were here to earn our keep. What was there for Ma to say?

As for Auntie, she folded her arms across her chest and stared off into the distance past Uncle’s shoulder, past the empty tables and booths. Perhaps she was looking out the windows into the dark of the empty parking lot, perhaps she wasn’t looking with her eyes at all, but was looking into her memories, remembering when she had a house full of servants and a closet full of French silk dresses.

And while she remembered these things, her face began to change. Her scar was still there, dividing her face into its light and dark halves, but I thought I could see something new growing, a hardening around the edges of her mouth where before there had only been slackness, a set to her jaw, a gleam to her eye. And for the first time, I began to worry about what it might be like to work for a woman like Auntie who had been wealthy once, a woman who had grown used to servants, the kind she punished when her own children had done something wrong.

I looked over at my sister Sourdi then, but she was following Ma’s example, casting her eyes down at the table.

All at once, Ma stood up abruptly and gathered up the empty rice bowls, the platters of food, the soup tureen. She balanced them against the length of her arm and then carried everything back into the kitchen.

Sourdi rose next and gathered up the chopsticks and spoons, the dirty napkins full of bones and gristle, scraping the dropped and dribbled food from the table top into her cupped hand, and then followed Ma into the kitchen.

Auntie turned to stare at me, her dark eyes glittering above her serpentine scar, and I stared back at her until she grew uncomfortable, or perhaps merely bored, and she turned away again.

I could not sleep that night. The wind blew fiercely, making the cornfields across from the house creak like bamboo. Wispy clouds covered the moon, its blue light only able to seep out in milky strands. It was a night when the dead could roam freely, when the souls of the unburied and the unblessed rode on the wind, whispering in the dark.

The house creaked and groaned, little feet scampered in the attic, the pipes in the walls hissed. When I closed my eyes, I could feel the dark pressing closer, sitting on my chest, icy hands around my throat.

I tried to keep Sourdi awake as long as possible. I begged her to tell me stories, but she was tired. She had helped Ma and the cook all day in the kitchen, preparing the dishes no one would order. She fell asleep almost as soon as her head lay back against her pillow. I tried to burrow closer to her, but the scents of the kitchen still clung to her skin. She no longer smelled like my sister, but burnt chilies and congealed fat, over-cooked chicken and too many shrimp.

I lay on my back, listening to the house teeter in the wind.

Finally, when I could stand it no more, I got up and went to look for Ma. The hallway outside our room was dark as a midnight river and drafty from the window opened in the stairwell. The wind swirled around me like a swiftly moving current. The voices of the dead were louder now, impossible to dismiss, hissing directly into my ears. And then I realized, the voices I heard were coming from Auntie and Uncle’s bedroom at the end of the hall. Auntie and Uncle were arguing, their voices circling each other like caged tigers, round and round, a snarl here, then a growl. I couldn’t make out everything they said, my Khmer was very rusty, but they were clearly arguing about us.

“You should never have invited them . . . ”

“What choice?”

“I can’t bear to see her face—”

I pressed my ears shut with my fingers and crept down the stairs towards Ma’s room, just off the kitchen. But when I got downstairs, I saw light spilling out the kitchen door, and found my mother sitting at the table, drinking a cup of hot water, and smoking.

“You should be in bed,” she whispered to me, spotting me peering in the door, but then she smiled and nodded for me to join her at the table. I slid onto one of the wooden chairs besides Ma; it felt cool against my bare legs.

“We should go, Ma,” I said. “Let’s just pack everything up again and go home.”

“This is home,” Ma said, blowing a perfect smoke ring towards the ceiling. It rose unsteadily, wobbling like a spinning saucer. “Why do you want to leave so soon? We have such a nice, big house to live in. Our own business.”

“It’s not ours, it’s Auntie’s. And Uncle’s. And they don’t need us here. There’s no customers. Even if Uncle’s gone to work, Auntie could run everything herself.”

“That’s why we’re lucky,” Ma insisted. “They don’t need us, but they invited us to come anyway.”

In the smokey yellow light of the kitchen, Ma’s face almost seemed to glow. The shadows under her eyes were less visible, the lines that pulled at the edges of her mouth were almost gone. She reached across the table and caught hold of my wrist with one hand.

“I’m not afraid of hard work,” Ma said, smoke emerging from her mouth in a series of small, blue clouds. “Nor should my children be afraid.” Her fingers tightened uncomfortably around my wrist then, but I didn’t try to pull my hand free.

“I’m not afraid,” I said, and Ma nodded happily.

“That’s my good girl.” She patted my wrist, her fingers stroking my skin softly, and for that moment her rough fingers felt smooth again, like silk, like smoke.

I let her be happy then. I let her think that I was a good daughter, the kind she wanted, the kind she deserved. But really, I was a terrible daughter, the kind who lied.